Headquarters, Department of the Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Abu Ghraib Convictions: a Miscarriage of Justice

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 32 Article 4 9-1-2013 The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice Robert Bejesky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Bejesky, The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice, 32 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 103 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ABU GHRAIB CONVICTIONS: A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE ROBERT BEJESKYt I. INTRODUCTION ..................... ..... 104 II. IRAQI DETENTIONS ...............................107 A. Dragnet Detentions During the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq.........................107 B. Legal Authority to Detain .............. ..... 111 C. The Abuse at Abu Ghraib .................... 116 D. Chain of Command at Abu Ghraib ..... ........ 119 III. BASIS FOR CRIMINAL CULPABILITY ..... ..... 138 A. Chain of Command ....................... 138 B. Systemic Influences ....................... 140 C. Reduced Rights of Military Personnel and Obedience to Authority ................ ..... 143 D. Interrogator Directives ................ .... -

Rebuilding Iraqi Television: a Personal Account

Rebuilding Iraqi Television: A Personal Account By Gordon Robison Senior Fellow USC Annenberg School of Communication October, 2004 A Project of the USC Center on Public Diplomacy Middle East Media Project USC Center on Public Diplomacy 3502 Watt Way, Suite 103 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org USC Center on Public Diplomacy – Middle East Media Project Rebuilding Iraqi Television: A Personal Account By Gordon Robison Senior Fellow, USC Annenberg School of Communication October 27, 2003 was the first day of Ramadan. It was also my first day at a new job as a contractor with the Coalition Provisional Authority, the American-led administration in Occupied Iraq. I had been hired to oversee the news department at Iraqi television. I had been at the station barely an hour when news of a major attack broke: at 8:30am a car bomb had leveled the Red Cross headquarters. The blast was enormous, and was heard across half the city. When the pictures began to come in soon afterwards they were horrific. The death toll began to mount. Then came word of more explosions: car bombs destroying three Iraqi police stations. A fourth police station was targeted but the bomber was intercepted in route. At times like this the atmosphere in the newsroom at CNN, the BBC or even a local television station is focused, if somewhat chaotic. Most news operations have a plan for dealing with big, breaking stories. Things in the newsroom move quickly, and they can get very stressful, but things do happen. Also, this was hardly the first time an atrocity like this had taken place. -

In the Shadow of General Marshall-Old Soldiers in The

In The Shadow of General Marshall: Old Soldiers in the Executive Branch Ryan Edward Guiberson Anaconda, Montana Bachelor of Science, United States Air Force Academy, 1992 Master of Arts-Political Science, University of Florida, 1994 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia August, 2013 2 Abstract: The usurpation of political authority by tyrannical military figures is a theme that pervades the history of politics. The United States has avoided such an occurrence and the prospect of a military coup d’etat rarely registers as a realistic concern in American politics. Despite the unlikelihood of this classic form of military usurpation, other more insidious forms lurk and must be guarded against to protect civilian control of the military. One potential manifestation has been referred to as a military colonization of the executive branch. This form implies that retired senior military officers increasingly pursue executive branch positions and unduly promote the interests of the active duty military, its leaders, and military solutions to national security issues. This work addresses military colonization claims by examining the number of retired senior military officers that have served in executive branch positions, trends in where they participate, and their political behavior in these positions. It also uses interviews with retired senior military officers to gain their perspectives on the incentives and disincentives of executive branch service. The study concludes that in the post-Cold War period, participation rates of retired senior military officers in key executive branch positions do not diverge significantly from broader post-World War II patterns. -

Dodsenior Leadership Compiled by June Lee, Editorial Associate

DODSenior Leadership Compiled by June Lee, Editorial Associate KEY: ADUSD Assistant Deputy Undersecretary of Defense ASD Assistant Secretary of Defense ATSD Assistant to the Secretary of Defense DASD Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense DATSD Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of Defense DUSD Deputy Undersecretary of Defense PADUSD Principal Assistant Deputy Undersecretary of Defense PDASD Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense PDATSD Principal Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of Defense PDUSD Principal Deputy Undersecretary of Defense USD Undersecretary of Defense Secretary of Defense Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates Gordon England ASD, Legislative Affairs ASD, Networks & Information ASD, Public Affairs ATSD, Intelligence Robert Wilkie Integration & Chief Information Officer Vacant Oversight John G. Grimes William Dugan (acting) PDASD, Legislative Affairs DASD, PA (Media) Robert R. Hood PDASD, NII Bryan Whitman DASD, Senate Affairs Cheryl J. Roby DASD, PA (Internal Communications Robert Taylor DASD, Information Management, & Public Liaison) Allison Barber DASD, House Affairs Integration, & Technology Virginia Johnson David M. Wennergren DASD, C3 Policies, Programs, & Space Programs Ron Jost DASD, Resources Bonnie Hammersley (acting) DASD, C3ISR & IT Acquisition Tim Harp (acting) DASD, Information & Identity Assurance Robert Lentz Dir., Administration & Dir., Operational Dir., Program Analysis General Counsel Inspector General Management Test & Evaluation & Evaluation William J. Haynes II Claude M. Kicklighter Michael B. Donley Charles E. McQueary Bradley M. Berkson 50 AIR FORCE Magazine / March 2008 Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics Dir., Acquisition, Resources & Analysis DUSD, Installations & Environment Nancy L. Spruill Alex A. Beehler (acting) Dir., International Cooperation ADUSD, Installations Alfred D. Volkman John C. Williams Dir., Special Programs ADUSD, Environment, Safety, & Occupational Brig. Gen. Paul G. -

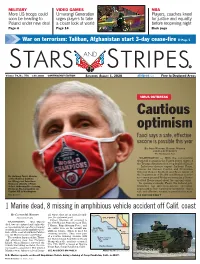

Cautious Optimism Fauci Says a Safe, Effective Vaccine Is Possible This Year

MILITARY VIDEO GAMES NBA More US troops could Umurangi Generation Players, coaches kneel soon be heading to urges players to take for justice and equality Poland under new deal a closer look at world before reopening night Page 4 Page 14 Back page War on terrorism: Taliban, Afghanistan start 3-day cease-fire » Page 5 Volume 79, No. 75A ©SS 2020 CONTINGENCY EDITION SATURDAY, AUGUST 1, 2020 stripes.com Free to Deployed Areas VIRUS OUTBREAK Cautious optimism Fauci says a safe, effective vaccine is possible this year BY JOHN WAGNER, RACHEL WEINER AND COLBY ITKOWITZ The Washington Post WASHINGTON — With the coronavirus death toll soaring in the United States, three of the Trump administration’s top health officials — Infectious-disease expert Anthony Fauci, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield and Brett Giroir of the Department of Health and Human Servic- Dr. Anthony Fauci, director es — were pressed Friday morning by a Demo- of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious crat-led House panel about the ongoing crisis. Diseases attends a House In opening remarks, Fauci, the federal gov- Select Subcommittee hearing ernment’s top infectious-disease specialist, Friday on the coronavirus on again said he was “cautiously optimistic” that a Capitol Hill in Washington. safe and effective vaccine is possible this year. ERIN SCOTT/AP SEE FAUCI ON PAGE 7 1 Marine dead, 8 missing in amphibious vehicle accident off Calif. coast BY CAITLIN M. KENNEY tal, where they are in critical condi- Stars and Stripes tion, the statement said. CALIFORNIA Fifteen Marines, all assigned to WASHINGTON — One Marine the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit, died, two are injured and eight oth- I Marine Expeditionary Force, and ers are missing at sea after a training San one sailor were on the assault am- SANTA Clemente accident in an assault amphibious ve- ATALINA phibious vehicle, which is used for C hicle off the coast of southern Califor- ISLAND Camp storming beaches. -

Disjointed War: Military Operations in Kosovo, 1999

Disjointed War Military Operations in Kosovo, 1999 Bruce R. Nardulli, Walter L. Perry, Bruce Pirnie John Gordon IV, John G. McGinn Prepared for the United States Army Approved for public release; distribution unlimited R Arroyo Center The research described in this report was sponsored by the United States Army under contract number DASW01-01-C-0003. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Disjointed war : military operations in Kosovo, 1999 / Bruce R. Nardulli ... [et al.]. p. cm. “MR-1406.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8330-3096-5 1. Kosovo (Serbia)—History—Civil War, 1998—Campaigns. 2. North Atlantic Treaty Organization—Armed Forces—Yugoslavia. I. Nardulli, Bruce R. DR2087.5 .D57 2002 949.703—dc21 2002024817 Cover photos courtesy of U.S. Air Force Link (B2) at www.af.mil, and NATO Media Library (Round table Meeting) at www.nato.int. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Stephen Bloodsworth © Copyright 2002 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2002 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 102, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] PREFACE Following the 1999 Kosovo conflict, the Army asked RAND Arroyo Center to prepare an authoritative and detailed account of military operations with a focus on ground operations, especially Task Force Hawk. -

Transcription Services by Ryan&Associates

National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations 1730 M St NW, Suite 503 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: +1-202-293-6466 Fax: +1-202-293-7770 Web: ncusar.org 23rd Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference Framing and Charting the Region’s Issues, Interests, Challenges, and Opportunities: Implications for Arab and U.S. Policies Washington, D.C. October 28, 2014 “ARAB-U.S. DEFENSE COOPERATION” Chair: Mr. Christopher Blanchard – Specialist in Middle East Affairs in the Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. Speakers: The Honorable Mark T. Kimmitt - Former Assistant Secretary for Political- Military Affairs, U.S. Department of State; former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Middle East Policy, U.S. Department of Defense; Retired General, U.S. Army; former Deputy Director for Plans and Strategy, U.S. Central Command. Dr. John Duke Anthony - Founding President and CEO, National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. Professor David Des Roches - Associate Professor and Senior Military Fellow, Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University; National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Malone Fellow in Arab and Islamic Studies to Syria. Dr. Kenneth Katzman - Specialist in Middle East Affairs in the Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. Dr. Imad Harb - Distinguished International Affairs Fellow, National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations; former Senior Researcher in Strategic Studies, Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (Abu Dhabi, UAE). Remarks as delivered. [Mr. Christopher Blanchard] Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. We’re joined on our panel here by Dr. Kenneth Katzman, my colleague, a specialist in the Middle East section at the Congressional Research Service. -

42, the Erosion of Civilian Control Of

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" UNITED STATES AIR FORCE ACADEMY Develops and inspires air and space leaders with vision for tomorrow. The Erosion of Civilian Control of the Military in the United States Today Richard H. Kohn University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History Number Forty-Two United States Air Force Academy Colorado 1999 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Lieutenant General Hubert Reilly Harmon Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon was one of several distinguished Army officers to come from the Harmon family. His father graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1880 and later served as Commandant of Cadets at the Pennsylvania Military Academy. Two older brothers, Kenneth and Millard, were members of the West Point class of 1910 and 1912, respectively. The former served as Chief of the San Francisco Ordnance District during World War II; the latter reached flag rank and was lost over the Pacific during World War II while serving as Commander of the Pacific Area Army Air Forces. Hubert Harmon, born on April 3, 1882, in Chester, Pennsylvania, followed in their footsteps and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1915. Dwight D. Eisenhower also graduated in this class, and nearly forty years later the two worked together to create the new United States Air Force Academy. Harmon left West Point with a commission in the Coast Artillery Corps, but he was able to enter the new Army air branch the following year. -

JP 3-05, Special Operations

Joint Publication 3-05 Special Operations 16 July 2014 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides overarching doctrine for special operations and the employment and support for special operations forces across the range of military operations. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS). It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations and provides the doctrinal basis for interagency coordination and for US military involvement in multinational operations. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders and prescribes joint doctrine for operations, education, and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing their appropriate plans. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the joint force commander from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the joint force commander deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of the overall objective. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders of combatant commands, subunified commands, joint task forces, subordinate components of these commands, the Services, and combat support agencies. b. The guidance in this publication is authoritative; as such, this doctrine will be followed except when, in the judgment of the commander, exceptional circumstances dictate otherwise. If conflicts arise between the contents of this publication and the contents of Service publications, this publication will take precedence unless the CJCS, normally in coordination with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has provided more current and specific guidance. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3937

May 3, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S3937 enough for us to give speeches on the hurting the bottom line, forcing farm- Vitter modified amendment No. 3628, to floor and do nothing, and this week we ers out of business, forcing businesses base the allocation of hurricane disaster re- will do nothing when it comes to the to lay off employees. Of course, those lief and recovery funds to States on need and physical damages. energy issue. There are things we must businesses depending on energy Wyden amendment No. 3665, to prohibit the do. First, we have to acknowledge that couldn’t even dream of expanding at use of funds to provide royalty relief for the what we have done has not worked. It this point because they have to find a production of oil and natural gas. has failed. The energy plan that was way to deal and cope with this reality. Santorum modified amendment No. 3640, to endorsed by the Republican majority What do we need to do? We need to increase by $12,500,000 the amount appro- and signed by the President last Au- punish the profiteers. We to need to priated for the Broadcasting Board of Gov- gust has failed. It has failed and obvi- say to these oil companies: This is in- ernors, to increase by $12,500,000 the amount ously so. tolerable. appropriated for the Department of State for During the heating season this last the Democracy Fund, to provide that such It is time for the President of the funds shall be made available for democracy winter, we saw dramatic runups in the United States to call the oil company programs and activities in Iran, and to pro- cost of home heating, whether it was executives into the Oval Office, to sit vide an offset. -

Introducing Clinical Legal Education Into Iraqi Law Schools

Toward a Rule Of Law Society In Iraq: Introducing Clinical Legal Education into Iraqi Law Schools By Haider Ala Hamoudi* INTRODUCTION The current condition of Iraqi law schools is extremely poor. 1 Once among the most prestigious in the Middle East,2 law schools in Iraq have deteriorated substantially during the past two decades for several reasons. First, the totalitar- ian regime of Saddam Hussein, hostile to the rule of law and to the establish- ment of consistent legal order, viewed the legal system and its educational component with suspicion. 3 Thus, the former regime underfunded, 4 understaf- * Clinical Educational Specialist, International Human Rights Law Institute, DePaul Univer- sity School of Law; J.D., Columbia University School of Law, 1996. 1. Given the near total absence of scholarly research on the subject of Iraqi universities prior to the fall of Saddam Hussein, there is very little written information available respecting the current condition of the law schools. As a result, much of the information contained in this article has been gathered through personal observations and numerous interviews with the deans, faculty, staff, and students of various Iraqi law schools, as well as Iraqi lawyers and judges. In all, my colleagues and I have spoken with hundreds of people since December 2003. For reasons of both clarity and security, I do not refer to each of the persons with whom I spoke or the exact dates on which I spoke with them, but rather refer to all such discussions collectively as "Conversations." 2. Eric Davis, Baghdad's Buried Treasure, N.Y. -

June 26, 2008 2Nd Update

SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SES I { CONVENED JANUARY 4, 2007 s ON ADJOURNED DECEMBER 31,2007 SECOND SESSION { CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2008 EXECUTIVE CALENDAR Thursday, June 26, 2008 *(updated at 8:00 p.m.) PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF NANCY ERICKSON, SECRETARY OF THE SENATE By Michelle Haynes, Executive Clerk *2d update Issue No. 279 1 RESOLUTIONS CALENDAR S. REs. No. No. SUBJECT REPORTED BY 2 TREATIES CALENDAR TREATY REPORTED No. Doc. No. SUBJECT BY 9 103-39 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Dec 19, 2007 Reported by Mr. Biden, Committee on Foreign Relations with printed Ex. Rept.ll0-9 and a resolution of advice and consent to ratification with declarations, understandings, and conditions. 10 110-9 Protocol of Amendments to Convention on Jun 26, 2008 Reported by Mr. International Hydrographic Organization Biden, Committee on Foreign Relations with printed Ex. Rept.ll0-10 and a resolution of advice and consent to ratification. 3 NOMINATIONS CALENDAR MESSAGE No No NOMINEE, OFFICE, AND PREDECESSOR REPORTED BY UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT * 206 73 James R. Kunder, of Virginia, to be Deputy Jun 27,2007 Reported by Mr. Administrator of the United States Agency for Biden, Committee on Foreign International Development, vice Frederick W. Relations, without printed Schieck. report. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 292 184 Rosa Emilia Rodriguez-Velez, of Puerto Rico, to Aug 03, 2007 Reported by Mr. be United States Attorney for the District of Leahy, Committee on the Puerto Rico for the term of four years, vice Judiciary, without printed Humberto S.