Reducing the Computer Waste Stream in the United States AUTHORS S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automated Waste Collection – How to Make Sure It Makes Sense for Your Community

AUTOMATED WASTE COLLECTION – HOW TO MAKE SURE IT MAKES SENSE FOR YOUR COMMUNITY Marc J. Rogoff, Ph.D. Richard E. Lilyquist, P.E. SCS Engineers Public Works Department Tampa, Florida City of Lakeland Lakeland, Florida Donald Ross Jeffrey L. Wood Kessler Consulting, Inc Solid Waste Division Tampa, Florida City of Lakeland Lakeland, Florida ABSTRACT Automated side-load trucks were first implemented in the City of Phoenix in the 1970s with the aim of ending The decision to implement solid waste collection the back-breaking nature of residential solid waste automation is a complex one and involves a number of collection, and to minimize worker injuries. Since then factors that should be considered, including engineering, thousands of public agencies and private haulers have risk management, technology assessment, costs, and moved from the once traditional read-load method of public acceptance. This paper analyzes these key issues waste collection to one that also provides the customer and provides a case study of how waste collection with a variety of choices in standardized, rollout carts. automation was considered by the City of Lakeland, These automated programs have enabled communities Florida. throughout the country to significantly reduce worker compensation claims and minimize insurance expenses, HOW DID AUTOMATED COLLECTION GET while at the same time offer opportunities to workers STARTED? who are not selected for their work assignment based solely on physical skills. The evolution of solid waste collection vehicles has been historically driven by an overwhelming desire by solid MODERN APPLICATION OF AUTOMATION waste professionals to collect more waste for less money, as well as lessening the physical demands on sanitation In an automated collection system, residents are provided workers. -

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, Policy Responses, and the Role of International Co-Operation and Trade

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, policy responses, and the role of international co-operation and trade POLICY PERSPECTIVES OECD ENVIRONMENT POLICY PAPER NO. 12 OECD . 3 This Policy Paper comprises the Background Report prepared by the OECD for the G7 Environment, Energy and Oceans Ministers. It provides an overview of current plastics production and use, the environmental impacts that this is generating and identifies the reasons for currently low plastics recycling rates, as well as what can be done about it. Disclaimers This paper is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. For Israel, change is measured between 1997-99 and 2009-11. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Copyright You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

Shameek Vats UPCYCLING of HOSPITAL TEXTILES INTO FASHIONABLE GARMENTS Master of Science Thesis

Shameek Vats UPCYCLING OF HOSPITAL TEXTILES INTO FASHIONABLE GARMENTS Master of Science Thesis Examiner: Professor Pertti Nousiainen and university lecturer Marja Rissanen Examiner and topic approved by the Council, Faculty of Engineering Sci- ences on 6 May 2015 i ABSTRACT TAMPERE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Master‘s Degree Programme in Materials Engineering VATS, SHAMEEK: Upcycling of hospital textiles into fashionable garments Master of Science Thesis, 64 pages, 3 Appendix pages July 2015 Major: Polymers and Biomaterials Examiner: Professor Pertti Nousianen and University lecturer Marja Rissanen Keywords: Upcycling, Textiles, Cotton polyester fibres, Viscose fibres, Polymer Fibers, Degradation, Life Cycle Assessment(LCA), Recycling, Cellulose fibres, Waste Hierarchy, Waste Management, Downcycling The commercial textile circulation in Finland works that a company is responsi- ble for supplying and maintenance of the textiles. The major customers include hospitals and restaurants chains. When the textiles are degraded and unsuitable for use, a part of it is acquired by companies, like, TAUKO Designs for further use. The rest part is unfortunately sent to the landfills. We tried to answer some research questions, whether the waste fabrics show the properties good enough to be used to manufacture new garments. If the prop- erties of the waste textiles are not conducive enough to be made into new fab- rics,whether or not other alternatives could be explored. A different view of the thesis also tries to reduce the amount of textile waste in the landfills by explor- ing different methods. This was done by characterizing the waste for different properties. The amount of cellulose polyester fibres was calculated along with breaking force and mass per unit area. -

International E-Waste Management Practice Country Factsheets from Twelve Jurisdictions

International e-Waste Management Practice Country Factsheets from Twelve Jurisdictions Deepali Sinha Khetriwal Grishma Jain Final version 2021 Authors Deepali Sinha Khetriwal, Grishma Jain Publication year 2021 ISBN 978-3-906177-28-1 Acknowledgment MedThisica reportl and has E lbeenect developedronic W withiastne a Mcollaborationanagem ofe thent SRI project with the National Policy Framework for Sustainable Management of E-wastePr oinj Egypt,ect executed by Environics in association with CEDARE and Sofies. The National Policy Framework project was mandated within the Medical and Electronic Waste Management Project, implemented by the Ministry of Environment and financed by UNDP/GEF. National Policy Framework for Sustainable Management of E-waste in Egypt (Technical Proposal) by: 6 Dokki St. 12th Floor, Giza 12311 Tel.: (+2010) 164 81 84 – (+202) 376 015 95 – 374 956 86 / 96 Fax: (+202) 333 605 99 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environics.org in association with: Licence Unless marked otherwise, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC-BY- SA 3.0) license. Additional rights clearance may be necessary for the elements that do not fall under the CC-BY-SA 3.0 license. Turning waste intoMar resourcesch 2019 for development SRI builds capacity for sustainable recycling in developing countries. The programme is funded by the Swiss State Secretariat of Economic Affairs (SECO) and is implemented by the Institute for Materials Science & Technology (Empa) and the World Resources sustainable-recycling.org Forum (WRF). It builds on the success of implementing e-waste recycling systems [email protected] together with various developing countries since more than ten years. -

The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, Flows, and the Circular Economy Potential

The Global E-waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, flows, and the circular economy potential Authors: Vanessa Forti, Cornelis Peter Baldé, Ruediger Kuehr, Garam Bel Contributions by: S. Adrian, M. Brune Drisse, Y. Cheng, L. Devia, O. Deubzer, F. Goldizen, J. Gorman, S. Herat, S. Honda, G. Iattoni, W. Jingwei, L. Jinhui, D.S. Khetriwal, J. Linnell, F. Magalini, I.C. Nnororm, P. Onianwa, D. Ott, A. Ramola, U. Silva, R. Stillhart, D. Tillekeratne, V. Van Straalen, M. Wagner, T. Yamamoto, X. Zeng Supporting Contributors: 2 The Global E-waste Monitor 2020 Quantities, flows, and the circular economy potential Authors: Vanessa Forti, Cornelis Peter Baldé, Ruediger Kuehr, Garam Bel Contributions by: S. Adrian, M. Brune Drisse, Y. Cheng, L. Devia, O. Deubzer, F. Goldizen, J. Gorman, S. Herat, S. Honda, G. Iattoni, W. Jingwei, L. Jinhui, D.S. Khetriwal, J. Linnell, F. Magalini, I.C. Nnororm, P. Onianwa, D. Ott, A. Ramola, U. Silva, R. Stillhart, D. Tillekeratne, V. Van Straalen, M. Wagner, T. Yamamoto, X. Zeng 3 Copyright and publication information 4 Contact information: Established in 1865, ITU is the intergovernmental body responsible for coordinating the For enquiries, please contact the corresponding author C.P. Baldé via [email protected]. shared global use of the radio spectrum, promoting international cooperation in assigning satellite orbits, improving communication infrastructure in the developing world, and Please cite this publication as: establishing the worldwide standards that foster seamless interconnection of a vast range of Forti V., Baldé C.P., Kuehr R., Bel G. The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, communications systems. From broadband networks to cutting-edge wireless technologies, flows and the circular economy potential. -

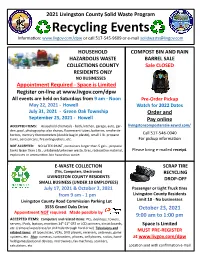

2021 Livingston County Solid Waste Program Recycling Events Information: Or Call 517-545-9609 Or E-Mail [email protected]

2021 Livingston County Solid Waste Program Recycling Events Information:www.livgov.com/dpw or call 517-545-9609 or e-mail [email protected] HOUSEHOLD COMPOST BIN AND RAIN HAZARDOUS WASTE BARREL SALE COLLECTIONS COUNTY Sale CLOSED RESIDENTS ONLY NO BUSINESSES Appointment Required - Space is Limited Register on-line at www.livgov.com/dpw All events are held on Saturdays from 9 am - Noon Pre-Order Pickup May 22, 2021 - Howell Watch for 2022 Dates July 31, 2021 - Green Oak Township Order and September 25, 2021 - Howell Pay online ACCEPTED ITEMS: Household chemicals - bath, kitchen, garage, auto, gar- livingstoncompostersale.ecwid.com/ den, pool, photography; also sharps, fluorescent tubes, batteries, smoke de- tectors, mercury thermometers (double bag in plastic), small 1 lb. propane Call 517-546-0040 tanks, aerosol cans, fire extinguishers, etc. For pickup information NOT ACCEPTED: NO LATEX PAINT, containers larger than 5 gals., propane tanks larger than 1 lb., unlabeled/unknown waste, tires, radioactive material, Please bring e-mailed receipt. explosives or ammunition, bio hazardous waste. E-WASTE COLLECTION SCRAP TIRE (TVs, Computers, Electronics) RECYCLING LIVINGSTON COUNTY RESIDENTS DROP-OFF SMALL BUSINESS (UNDER 10 EMPLOYEES) July 17, 2021 & October 2, 2021 Passenger or Light Truck tires from 9 am - 1 pm Livingston County Residents Limit 10 - No businesses Livingston County Road Commission Parking Lot 3535 Grand Oaks Drive October 23, 2021 Appointment NOT required. Made possible by 9:00 am to 1:00 pm ACCEPTED ITEMS: Computers and related items: PCs, desktops, towers, servers, iPads, laptops, monitors 14”-21” CRT or LCD; printers, circuit boards, Space Is Limited etc. -

Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers

Scam Recycling e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers The e-Trash Transparency Project Front Cover: One of what are believed to be 100’s of electronics junkyards in Hong Kong’s New Territories region, receiving US e-waste. The junkyards break apart the equipment using dangerous, polluting methods. ©BAN 2016 Back Inside Cover: KCTS producer Katie Campbell with Jim Puckett on the trail in New Territories, Hong Kong. ©KCTS, Earthfix Program, 2016. Back Cover: A pile of broken Cold Cathode Fluorescent Lamps (CCFLs) from flat screen monitors imported from the US. CCFLs contain the toxic element mercury. ©BAN 2016. Page 2 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Made Possible by a Grant from: The Body Shop Foundation Basel Action Network 206 1st Ave. S. Seattle, WA 98104 Phone: +1.206.652.5555 Email: [email protected], Web: www.ban.org Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Page 3 Page 4 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Acknowledgements Authors: Eric Hopson, Jim Puckett Editors: Hayley Palmer, Sarah Westervelt Layout & Design: Jennifer Leigh, Eric Hopson Site Investigative Teams Hong Kong: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Ms. Dongxia (Evana) Su, Chinese, journalist and fixer Mr. Sanjiv Pandita, Indian/Hong Kong director of Asia Monitor Resource Centre Mr. Aurangzaib (Ali) Khan, Pakistani/Hong Kong, trader Guiyu, China: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Mr. Michael Standaert, American, journalist, Bloomberg BNA Mr. -

How to Implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) a Briefing For

23 August 2019 How to implement extended producer responsibility (EPR) A briefing for governments and businesses By: Emma Watkins Susanna Gionfra Funded by Disclaimer: The arguments expressed in this report are solely those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinion of any other party. The report should be cited as follows: E. Watkins and S. Gionfra (2019) How to implement extended producer responsibility (EPR): A briefing for governments and businesses Corresponding author: Emma Watkins Acknowledgements: We thank Xin Chen and Annika Lilliestam of WWF Germany for their inputs and comments during the preparation of this briefing. Cover image: Pexels Free Stock Photos Institute for European Environmental Policy AISBL Brussels Office Rue Joseph II 36-38 1000 Bruxelles Belgium Tel: +32 (0) 2738 7482 Fax: +32 (0) 2732 4004 London Office 11 Belgrave Road IEEP Offices, Floor 3 London, SW1V 1RB Tel: +44 (0) 20 7799 2244 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7799 2600 The Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) is an independent not-for-profit institute. IEEP undertakes work for external sponsors in a range of policy areas as well as engaging in our own research programmes. For further information about IEEP, see our website at www.ieep.eu or contact any staff member. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction and context for this briefing .................................................................. 7 2 Introduction to extended -

Electronic Waste Management Report

ELECTRONIC WASTE MANAGEMENT IN VERMONT January 2004 Agency Of Natural Resources Department Of Environmental Conservation 1 Table of Contents DEFINITION OF ELECTRONIC PRODUCTS................................................................. 3 WHY ARE USED ELECTRONICS A CONCERN? .......................................................... 3 HOW ARE COMPUTERS RECYCLED?........................................................................... 6 STATE AND NATIONAL INITIATIVES ........................................................................... 7 VERMONT’S PROGRESS IN REUSING AND RECYCLING ELECTRONIC WASTE .................................................................................................................................... 8 VERMONT’S ELECTRONICS COLLECTION INFRASTRUCTURE ......................... 9 PILOT PROGRAMS.............................................................................................................. 9 CURRENT STATUS ............................................................................................................ 10 ISSUES AND TRENDS........................................................................................................ 11 CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................... 12 APPENDIXES....................................................................................................................... 13 ENDNOTES.......................................................................................................................... -

Table of Contents

Iowa Electronics Waste Characterization Study FINAL REPORT March, 2002 Submitted by: Wuf Technologies, LLC 7 South State Street Concord, NH 03301 603-224-7959 / fax 229-1960 email [email protected] Submitted to: Iowa Department of Natural Resources Attn: Merry Rankin Waste Management Assistance Bureau 502 East 9th Street Des Moines, IA 50319 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION ONE CURRENT GENERATION RATES AND RECYCLING PRACTICES 3 1.1 Commercial Sector 3 1.1.1 Commercial Sector CEE Generation 3 1.1.2 Commercial Sector CEE Management Practices 4 1.1.3 Barriers To Increased Recycling 7 1.2 Institutions 7 1.2.1 Institutional CEE Generation 7 1.2.2 Institutional CEE Management Practices 8 1.2.3 Barriers to Increased Recycling 8 1.3 Residential Sector 9 1.3.1 Residential CEE Generation 9 1.3.2 Assessment of Residential Electronics Collection and Recycling Efforts 12 1.3.3 Assessment of Collection Efforts Organized by Non-Government Organizations 14 SECTION TWO ALTERNATIVES TO INCREASE ELECTRONICS RECOVERY 17 2.1 Current Status of CEE Recycling 17 2.1.1 Overview of the Electronics Recycling Industry: U.S. 17 2.1.2 Overview of the Electronics Recycling Industry: Iowa 18 2.2 Summary of Barriers to Increased Recycling of CEE from All Sectors 20 2.2.1 Commercial Sector — Large Businesses 21 2.2.2 Commercial Sector — Small Businesses 22 2.2.3 Institutions 22 2.2.4 Residential Sector 23 2.3 Assessment of Laws, Regulations, Policies from Other States 23 SECTION THREE POLICY OPTIONS TO INCREASE ELECTRONICS RECYCLING 29 3.1 Comparative -

Municipal Curbside Compostables Collection: What Works and Why?

Municipal Curbside Compostables WHAT WORKS AND WHY? Collection MUNICIPAL CURBSIDE COMPOSTABLES COLLECTION What Works and Why? The Urban Sustainability Assessment (USA) Project: Identifying Effective Urban Sustainability Initiatives Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Pl: Judith A. Layzer ([email protected]) Citation: Judith A. Layzer and Alexis Schulman. 2014. Primary Researcher: “Municipal Curbside Compostables Collection: What Works and Why?” Alexis Schulman Work product of the Urban Sustainability Assessment (USA) Project, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Research Team: Yael Borofsky COPYRIGHT © 2014. All rights reserved. Caroline Howe Aditya Nochur Keith Tanner Louise Yeung Design: Gigi McGee Design CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i INTRODUCTION 1 THE CASES 4 THE CONTEXT FOR CURBSIDE COMPOSTABLES COLLECTION 10 DESIGNING AN EFFECTIVE CURBSIDE COMPOSTABLES COLLECTION PROGRAM 22 GETTING STARTED 36 CONCLUSIONS 42 REFERENCES 45 APPENDIX A: THE BENEFITS OF COMPOSTING 49 APPENDIX B: CASE STUDIES 52 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to the Summit Foundation, Renee Dello, Senior Analyst, Solid Waste Sue Patrolia, Recycling Coordinator, Townships Washington, D.C. for generously funding this Management Services, City of Toronto. of Hamilton and Wenham. project. In addition, for their willingness to speak openly and repeatedly about composting Kevin Drew, Residential Zero Waste Charlotte Pitt, Recycling Program Manager, in their cities, towns, and counties, we would Coordinator, San Francisco Department of Solid Waste Management, Denver Department like to thank the following people: the Environment. of Public Works. Bob Barrows, Waste Policy Coordinator, Dean Elstad, Recycling Coordinator, Department Andy Schneider, Recycling Program Manager, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. of Public Works, City of Minnetonka. Solid Waste Management Division, City of Berkeley. -

Waste Transfer Stations: a Manual for Decision-Making Acknowledgments

Waste Transfer Stations: A Manual for Decision-Making Acknowledgments he Office of Solid Waste (OSW) would like to acknowledge and thank the members of the Solid Waste Association of North America Focus Group and the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council Waste Transfer Station Working Group for reviewing and providing comments on this draft document. We would also like to thank Keith Gordon of Weaver Boos & Gordon, Inc., for providing a technical Treview and donating several of the photographs included in this document. Acknowledgements i Contents Acknowledgments. i Introduction . 1 What Are Waste Transfer Stations?. 1 Why Are Waste Transfer Stations Needed?. 2 Why Use Waste Transfer Stations? . 3 Is a Transfer Station Right for Your Community? . 4 Planning and Siting a Transfer Station. 7 Types of Waste Accepted . 7 Unacceptable Wastes . 7 Public Versus Commercial Use . 8 Determining Transfer Station Size and Capacity . 8 Number and Sizing of Transfer Stations . 10 Future Expansion . 11 Site Selection . 11 Environmental Justice Considerations . 11 The Siting Process and Public Involvement . 11 Siting Criteria. 14 Exclusionary Siting Criteria . 14 Technical Siting Criteria. 15 Developing Community-Specific Criteria . 17 Applying the Committee’s Criteria . 18 Host Community Agreements. 18 Transfer Station Design and Operation . 21 Transfer Station Design . 21 How Will the Transfer Station Be Used? . 21 Site Design Plan . 21 Main Transfer Area Design. 22 Types of Vehicles That Use a Transfer Station . 23 Transfer Technology . 25 Transfer Station Operations. 27 Operations and Maintenance Plans. 27 Facility Operating Hours . 32 Interacting With the Public . 33 Waste Screening . 33 Emergency Situations . 34 Recordkeeping. 35 Environmental Issues.