How to Implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) a Briefing For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Waste

Copyright © 2012 SAGE Publications. Not for sale, reproduction, or distribution. Mineral Waste 553 ity for many local governments in the early 21st cen- Water; Public Health; Residential Urban Refuse; Toxic tury, and this has led to budget cuts in public ser- Wastes; Waste Management, Inc. vices. In some places, this means less funding for waste management, which has led to policies like Further Readings twice-per-month garbage collection. Other finan- Environmental Protection Agency. “Illegal Dumping cially strapped places do not offer convenient loca- Prevention Guidebook.” http://www.epa.gov/wastes/ tions for disposal. Perhaps the most problematic conserve/tools/payt/pdf/illegal.pdf (Accessed July for residents are locations that charge high fees for 2010). waste disposal and recycling programs. In tough “Nonprofit Agencies Shoulder Burden of Illegal economic times, there is often not enough money Dumping.” Register-Guard (Eugene) (June 3, 2003). in the household budget to make ends meet, much Sigman, Hillary. “Midnight Dumping: Public Policies less to afford these garbage costs. This is especially and Illegal Disposal of Used Oil.” RAND true for low-income residents. These segments Journal of Economics, v.29/1 (1998). of the population often resort to more economi- cally viable measures, like midnight dumping, in order to dispose of their waste. There also tend to be higher crime rates in these areas, which law Mineral Waste enforcement gives a much higher priority than ille- gal dumping. Consequently, midnight dumping Mineral waste is the solid, liquid, and airborne by- goes unchecked. products of mining and mineral concentration pro- cesses. Although mining and metallurgy are ancient Solutions arts, the Industrial Revolution launched an accel- As a way to curb illegal dumping activity, the erating global demand for minerals that has made Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has sug- waste generation and disposal modern industry’s gested implementing “pay-as-you-throw” (PAYT) most severe environmental and social challenge. -

Redesign. Rethink. Reduce. Reuse. Go Beyond Recycling

REDESIGN. RETHINK. REDUCE. REUSE. GO BEYOND RECYCLING. WHAT IS ZERO WASTE? the entire lifecycle of products used within a facility. With TRUE, your facility can demonstrate to the world what you’re doing to minimize Zero waste is a philosophy that encourages the redesign of resource your waste output. life cycles so that all products are reused; a process that is very similar to the way that resources are reused in nature. Although recycling is HOW DOES CERTIFICATION WORK? the first step in the journey, achieving zero waste goes far beyond. By focusing on the larger picture, facilities and organizations can reap The TRUE Zero Waste certification program is an Assessor-based financial benefits while becoming more resource efficient. program that rates how well facilities perform in minimizing their non-hazardous, solid wastes and maximizing their efficient in the use According to the EPA, the average American generates 4.4 pounds of of resources. A TRUE project’s goal is to divert 90 percent or greater trash each day, and according to the World Bank, global solid waste overall diversion from the landfill, incineration (waste-to-energy) and generation is on pace to increase 70 percent by 2025. For every can of the environment for solid, non-hazardous wastes for the most recent garbage at the curb, for instance, there are 87 cans worth of materials 12 months. that come from extraction industries that manufacture natural resources into finished products—like timber, agricultural, mining and Certification is available for any physical facility and their operations, petroleum. This means that while recycling is important, it doesn’t including facilities owned by: companies, property managers, address the real problem. -

Reduce, Reuse and Recycle (The 3Rs) and Resource Efficiency As the Basis for Sustainable Waste Management

CSD-19 Learning Centre “Synergizing Resource Efficiency with Informal Sector towards Sustainable Waste Management” 9 May 2011, New York Co-organized by: UNCRD and UN HABITAT Reduce, Reuse and Recycle (the 3Rs) and Resource Efficiency as the basis for Sustainable Waste Management C. R. C. Mohanty UNCRD 3Rs offer an environmentally friendly alternatives to deal with growing generation of wastes and its related impact on human health, eco nomy and natural ecosystem Natural Resources First : Reduction Input Reduce waste, by-products, etc. Production (Manufacturing, Distribution, etc.) Second : Reuse Third : Material Recycling Use items repeatedly. Recycle items which cannot be reused as raw materials. Consumption Fourth : Thermal Recycling Recover heat from items which have no alternatives but incineration and which cannot Discarding be recycled materially. Treatment (Recycling, Incineration, etc.) Fifth : Proper Disposal Dispose of items which cannot be used by any means. (Source: Adapted from MoE-Japan) Landfill disposal Stages in Product Life Cycle • Extraction of natural resources • Processing of resources • Design of products and selection of inputs • Production of goods and services • Distribution • Consumption • Reuse of wastes from production or consumption • Recycling of wastes from consumption or production • Disposal of residual wastes Source: ADB, IGES, 2008 Resource efficiency refers to amount of resource (materials, energy, and water) consumed in producing a unit of product or services. It involves using smaller amount of physical -

Automated Waste Collection – How to Make Sure It Makes Sense for Your Community

AUTOMATED WASTE COLLECTION – HOW TO MAKE SURE IT MAKES SENSE FOR YOUR COMMUNITY Marc J. Rogoff, Ph.D. Richard E. Lilyquist, P.E. SCS Engineers Public Works Department Tampa, Florida City of Lakeland Lakeland, Florida Donald Ross Jeffrey L. Wood Kessler Consulting, Inc Solid Waste Division Tampa, Florida City of Lakeland Lakeland, Florida ABSTRACT Automated side-load trucks were first implemented in the City of Phoenix in the 1970s with the aim of ending The decision to implement solid waste collection the back-breaking nature of residential solid waste automation is a complex one and involves a number of collection, and to minimize worker injuries. Since then factors that should be considered, including engineering, thousands of public agencies and private haulers have risk management, technology assessment, costs, and moved from the once traditional read-load method of public acceptance. This paper analyzes these key issues waste collection to one that also provides the customer and provides a case study of how waste collection with a variety of choices in standardized, rollout carts. automation was considered by the City of Lakeland, These automated programs have enabled communities Florida. throughout the country to significantly reduce worker compensation claims and minimize insurance expenses, HOW DID AUTOMATED COLLECTION GET while at the same time offer opportunities to workers STARTED? who are not selected for their work assignment based solely on physical skills. The evolution of solid waste collection vehicles has been historically driven by an overwhelming desire by solid MODERN APPLICATION OF AUTOMATION waste professionals to collect more waste for less money, as well as lessening the physical demands on sanitation In an automated collection system, residents are provided workers. -

Pay As You Throw

FEATURE By Lisa Skumatz, economist and environmental/recycling/energy consultant, Town of Superior trustee and CML Executive Board member pay AS YOU THROW PAY AS YOU THROW is a trash rate put out more garbage – usually • Manual or automated collection strategy that charges households a measured either by the can or bag of trucks; higher bill for putting out more trash for garbage. Paying by volume (like paying • Wheelie or other types of containers; collection. Sounds fair — fee for service, for electricity, water, groceries, etc.) just as households are charged a higher provides households with an incentive • Urban (Boulder), suburban bill for using more water, electricity, etc. to recycle more and reduce disposal. (Lafayette) and small/rural areas (Aspen, Boulder County); and More than 7,000 (25 percent) of Communities have been implementing communities nationwide agree PAYT trash rate incentives in earnest • Set up by ordinance (Boulder and use some form of PAYT. since the late 1980s. The programs can County, Fort Collins), by contract The U.S. Environmental Protection provide a cost-effective method of (Lafayette) or city-run (Loveland). Agency Region 8 hopes to help more reducing landfill disposal, increasing How PAYT works Colorado cities and towns adopt PAYT recycling and improving equity, among The most common types of PAYT with a new program, offering free other effects. systems are: workshops, a dedicated Web site Experience in these 7,000 communities • Variable can or subscribed can (www.paytwest.org) and free consulting – including some right here in Colorado programs ask households to sign up for interested communities. – shows that these systems work very for a specific number of containers PAYT (also called variable rates, well in a variety of situations: (or size of wheelie container) as volume-based rates and other names) • Private haulers (Lafayette), multiple their usual garbage service and get provide a different way to bill for garbage haulers (Fort Collins) or city systems a bill that is higher for bigger service. -

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, Policy Responses, and the Role of International Co-Operation and Trade

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, policy responses, and the role of international co-operation and trade POLICY PERSPECTIVES OECD ENVIRONMENT POLICY PAPER NO. 12 OECD . 3 This Policy Paper comprises the Background Report prepared by the OECD for the G7 Environment, Energy and Oceans Ministers. It provides an overview of current plastics production and use, the environmental impacts that this is generating and identifies the reasons for currently low plastics recycling rates, as well as what can be done about it. Disclaimers This paper is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. For Israel, change is measured between 1997-99 and 2009-11. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Copyright You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

Shameek Vats UPCYCLING of HOSPITAL TEXTILES INTO FASHIONABLE GARMENTS Master of Science Thesis

Shameek Vats UPCYCLING OF HOSPITAL TEXTILES INTO FASHIONABLE GARMENTS Master of Science Thesis Examiner: Professor Pertti Nousiainen and university lecturer Marja Rissanen Examiner and topic approved by the Council, Faculty of Engineering Sci- ences on 6 May 2015 i ABSTRACT TAMPERE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Master‘s Degree Programme in Materials Engineering VATS, SHAMEEK: Upcycling of hospital textiles into fashionable garments Master of Science Thesis, 64 pages, 3 Appendix pages July 2015 Major: Polymers and Biomaterials Examiner: Professor Pertti Nousianen and University lecturer Marja Rissanen Keywords: Upcycling, Textiles, Cotton polyester fibres, Viscose fibres, Polymer Fibers, Degradation, Life Cycle Assessment(LCA), Recycling, Cellulose fibres, Waste Hierarchy, Waste Management, Downcycling The commercial textile circulation in Finland works that a company is responsi- ble for supplying and maintenance of the textiles. The major customers include hospitals and restaurants chains. When the textiles are degraded and unsuitable for use, a part of it is acquired by companies, like, TAUKO Designs for further use. The rest part is unfortunately sent to the landfills. We tried to answer some research questions, whether the waste fabrics show the properties good enough to be used to manufacture new garments. If the prop- erties of the waste textiles are not conducive enough to be made into new fab- rics,whether or not other alternatives could be explored. A different view of the thesis also tries to reduce the amount of textile waste in the landfills by explor- ing different methods. This was done by characterizing the waste for different properties. The amount of cellulose polyester fibres was calculated along with breaking force and mass per unit area. -

Designing out Waste: a Design Team Guide for Buildings

Uniclass A42: N462 CI/SfB (Ajp) (T6) Designing out Waste: A design team guide for buildings LESS WASTE, SHARPER DESIGN Halving Waste to Landfill “ Clients are making construction waste reduction a priority and design teams must respond. This stimulating guide to designing out construction waste clearly illustrates how design decisions can make a significant and positive difference, not only through reducing environmental impact but also making the most of resources. It’s a promising new opportunity for design teams, which I urge them to take up.” Sunand Prasad, RIBA President 1.0 Introduction 6 Contents 2.0 The case for action 8 2.1 Materials resource efficiency 10 2.2 Drivers for reducing waste 13 3.0 The five principles of Designing out Waste 14 3.1 Design for Reuse and Recovery 18 3.2 Design for Off Site Construction 20 3.3 Design for Materials Optimisation 23 3.4 Design for Waste Efficient Procurement 24 3.5 Design for Deconstruction and Flexibility 27 4.0 Project application of the five Designing out Waste principles 28 4.1 Client brief and designers’ appointments 31 4.2 RIBA Stage A/B: Appraisal and strategic brief 32 4.3 RIBA Stage C: Outline proposal 34 4.4 RIBA Stage D: Detailed proposals 38 4.5 RIBA Stage E: Technical design 40 5.0 Design review process 42 6.0 Suggested waste reduction initiatives 46 6.1 Design for Reuse and Recovery 48 6.2 Design for Off Site Construction 50 6.3 Design for Materials Optimisation 51 6.4 Design for Waste Efficient Procurement 52 6.5 Design for Deconstruction and Flexibility 53 Appendix A - The Construction Commitments: Halving Waste to Landfill 56 Appendix B - Drivers for reducing waste 57 Written by: Davis Langdon LLP ◀ Return to Contents This document provides information on the key principles that designers can use during the design process and how these Section 2.0 principles can be applied to projects to maximise opportunities Case for action – Presents to the construction industry the to Design out Waste. -

Reduce Reuse Recycle Compost

Loyola is committed to waste reduction as part of our sustainability efforts. For more information on how you can help reduce waste on campus, please review this summary of available programs. Reduce • Eliminate Disposables – Get out of the habit of single-use-items. With a set of reusable products (cutlery, mug, water bottle, bag), you can cut down on plastics and save money. • Sustainable Purchasing - Take time to implement thoughtful purchasing practices to conserve resources and save the university money. o Life-Cycle Considerations – Before you bring something to campus, think about the full impact of its use. How much energy or water will it consume? Is there a way to recycle it when it’s not needed? o Third-Party Certified – Considering purchasing equipment or materials that meet reputable certifications. o Change Your Use – Always print double-sided. Avoid purchasing what you don’t need. Eliminate packaging materials where you can. • Green Move-In – Consider what you bring to campus. Don’t bring ‘one-off’ or delicate items that become someone’s problem to dispose of. For more information on Sustainable Purchasing use the ‘Guide to Green Purchasing at Loyola’ or talk to Loyola’s Purchasing Department. Reuse • In Your Department – Many times we have materials that others can use. Set up a re-use center to share office supplies, conference left-overs, or other common materials. • Think Green and Give – At the end of each school year, Loyola student donate tons of clothes and household goods through this program in the Residence Halls. LUC.edu/thinkgreenandgive • Biodiesel Program – Loyola ‘upcycles’ waste vegetable oil into vehicle fuel, biosoap, and other products. -

Impacts of Pay-As-You-Throw Municipal Solid Waste Collection

City of Milwaukee: Impacts of Pay-As-You-Throw Municipal Solid Waste Collection Prepared by Catherine Hall Gail Krumenauer Kevin Luecke Seth Nowak For the City of Milwaukee, Department of Administration, Budget and Management Division Workshop in Public Affairs, Domestic Issues Public Affairs 869 Spring 2009 Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs University of Wisconsin-Madison ©2009 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. For additional copies: Publications Office La Follette School of Public Affairs 1225 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706 www.lafollette.wisc.edu/publications/workshops.html [email protected] The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs is a nonpartisan teaching and research department of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The school takes no stand on policy issues; opinions expressed in these pages reflect the views of the authors. ii Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures...................................................................................... iv Foreword ................................................................................................................. v Acknowledgments.................................................................................................. vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Research -

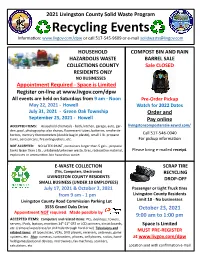

2021 Livingston County Solid Waste Program Recycling Events Information: Or Call 517-545-9609 Or E-Mail [email protected]

2021 Livingston County Solid Waste Program Recycling Events Information:www.livgov.com/dpw or call 517-545-9609 or e-mail [email protected] HOUSEHOLD COMPOST BIN AND RAIN HAZARDOUS WASTE BARREL SALE COLLECTIONS COUNTY Sale CLOSED RESIDENTS ONLY NO BUSINESSES Appointment Required - Space is Limited Register on-line at www.livgov.com/dpw All events are held on Saturdays from 9 am - Noon Pre-Order Pickup May 22, 2021 - Howell Watch for 2022 Dates July 31, 2021 - Green Oak Township Order and September 25, 2021 - Howell Pay online ACCEPTED ITEMS: Household chemicals - bath, kitchen, garage, auto, gar- livingstoncompostersale.ecwid.com/ den, pool, photography; also sharps, fluorescent tubes, batteries, smoke de- tectors, mercury thermometers (double bag in plastic), small 1 lb. propane Call 517-546-0040 tanks, aerosol cans, fire extinguishers, etc. For pickup information NOT ACCEPTED: NO LATEX PAINT, containers larger than 5 gals., propane tanks larger than 1 lb., unlabeled/unknown waste, tires, radioactive material, Please bring e-mailed receipt. explosives or ammunition, bio hazardous waste. E-WASTE COLLECTION SCRAP TIRE (TVs, Computers, Electronics) RECYCLING LIVINGSTON COUNTY RESIDENTS DROP-OFF SMALL BUSINESS (UNDER 10 EMPLOYEES) July 17, 2021 & October 2, 2021 Passenger or Light Truck tires from 9 am - 1 pm Livingston County Residents Limit 10 - No businesses Livingston County Road Commission Parking Lot 3535 Grand Oaks Drive October 23, 2021 Appointment NOT required. Made possible by 9:00 am to 1:00 pm ACCEPTED ITEMS: Computers and related items: PCs, desktops, towers, servers, iPads, laptops, monitors 14”-21” CRT or LCD; printers, circuit boards, Space Is Limited etc. -

Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers

Scam Recycling e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers The e-Trash Transparency Project Front Cover: One of what are believed to be 100’s of electronics junkyards in Hong Kong’s New Territories region, receiving US e-waste. The junkyards break apart the equipment using dangerous, polluting methods. ©BAN 2016 Back Inside Cover: KCTS producer Katie Campbell with Jim Puckett on the trail in New Territories, Hong Kong. ©KCTS, Earthfix Program, 2016. Back Cover: A pile of broken Cold Cathode Fluorescent Lamps (CCFLs) from flat screen monitors imported from the US. CCFLs contain the toxic element mercury. ©BAN 2016. Page 2 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Made Possible by a Grant from: The Body Shop Foundation Basel Action Network 206 1st Ave. S. Seattle, WA 98104 Phone: +1.206.652.5555 Email: [email protected], Web: www.ban.org Sept 15, 2016 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Page 3 Page 4 Scam Recycling: e-Dumping on Asia by US Recyclers Sept 15, 2016 Acknowledgements Authors: Eric Hopson, Jim Puckett Editors: Hayley Palmer, Sarah Westervelt Layout & Design: Jennifer Leigh, Eric Hopson Site Investigative Teams Hong Kong: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Ms. Dongxia (Evana) Su, Chinese, journalist and fixer Mr. Sanjiv Pandita, Indian/Hong Kong director of Asia Monitor Resource Centre Mr. Aurangzaib (Ali) Khan, Pakistani/Hong Kong, trader Guiyu, China: Mr. Jim Puckett, American, Director of the Basel Action Network Mr. Michael Standaert, American, journalist, Bloomberg BNA Mr.