Mineral Waste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illegal Dumping - a Serious Issue

Illegal Dumping - A Serious Issue Illegal Dumping is the improper disposal of waste at any location other than a permitted landfill or facility. Illegal dumping poses a threat to human health and the environment. Also known as open dumping or midnight dumping, illegal dumping usually happens in open areas, along roadsides, in wooded areas, streams and rivers, and frequently occurs late at night to avoid detection. The waste is dumped to avoid disposal fees or time and effort required for proper disposal. It is illegal to allow open dumping on your property. Property owners sometimes try to benefit financially by charging a fee for someone to dump waste on their property. This is illegal. What types of materials are commonly dumped? . construction and demolition debris like drywall, shingles, lumber, bricks, concrete and siding . large appliances and furniture . household garbage . medical waste . abandoned vehicles, parts and tires . yard waste or plant materials Why is illegal dumping a problem? The human health risks associated with illegal dumping are significant. Illegal dumps can be accessible to people who could come in contact with chemicals (fluids or dust) or get hurt from nails and sharp edges of materials. Illegal dumps also attract rodents and insects. For example, illegally dumped waste tires provide an ideal place for mosquitoes to breed. Mosquitoes multiply 100 times faster than normal in the warm, stagnant water collecting in waste tires. Dumps also result in a decrease in property values. Illegal dumping can impact proper drainage making areas more susceptible to flooding when debris blocks creeks, culverts and drainage basins. -

Prevent Illegal Open Dumping Office of Land Quality – Solid Waste Compliance Section

FACT SHEET INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Prevent Illegal Open Dumping Office of Land Quality – Solid Waste Compliance Section (317) 234-6923 • (800) 451-6027 www.idem.IN.gov 100 N. Senate Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46204 Introduction • Indiana’s open dumping rules (329 IAC 10-4) state, “No person shall cause or allow the storage, containment, processing, or disposal of solid waste in a manner which creates a threat to human health or the environment, including the creating of a fire hazard, vector attraction, air or water pollution, or other contamination.” • Discarding trash or unwanted items anywhere except recycling centers or state permitted landfills, transfer stations, or incinerators is considered open dumping and is illegal. • Burning waste materials, including household trash, business trash, construction/demolition debris, and dumped waste, is also illegal in Indiana. • Open dumps may be found on public or private property and are typically located in secluded areas such as woods or ravines, roadways, ditches, river and creek banks, vacant lots, and abandoned sites. • Dumped waste often includes household building debris, construction and demolition waste, household garbage, appliances, furniture, tires, plastics, cardboard, and hazardous waste—including household hazardous waste (HHW) such as used oil, weed killer, or swimming pool chemicals—that is corrosive, toxic, ignitable, and/or reactive. Some dumpsites may even contain abandoned vehicles or potentially dangerous chemicals and paraphernalia from illegal drug labs (e.g., meth labs). Potential Health, Environmental, and Community Impacts • Physical hazards at open dumps include broken glass, sharp metal, and hypodermic needles that can cause painful injuries; appliances in which children or animals can become trapped; and tires that may catch fire and emit toxic smoke. -

Pay As You Throw

FEATURE By Lisa Skumatz, economist and environmental/recycling/energy consultant, Town of Superior trustee and CML Executive Board member pay AS YOU THROW PAY AS YOU THROW is a trash rate put out more garbage – usually • Manual or automated collection strategy that charges households a measured either by the can or bag of trucks; higher bill for putting out more trash for garbage. Paying by volume (like paying • Wheelie or other types of containers; collection. Sounds fair — fee for service, for electricity, water, groceries, etc.) just as households are charged a higher provides households with an incentive • Urban (Boulder), suburban bill for using more water, electricity, etc. to recycle more and reduce disposal. (Lafayette) and small/rural areas (Aspen, Boulder County); and More than 7,000 (25 percent) of Communities have been implementing communities nationwide agree PAYT trash rate incentives in earnest • Set up by ordinance (Boulder and use some form of PAYT. since the late 1980s. The programs can County, Fort Collins), by contract The U.S. Environmental Protection provide a cost-effective method of (Lafayette) or city-run (Loveland). Agency Region 8 hopes to help more reducing landfill disposal, increasing How PAYT works Colorado cities and towns adopt PAYT recycling and improving equity, among The most common types of PAYT with a new program, offering free other effects. systems are: workshops, a dedicated Web site Experience in these 7,000 communities • Variable can or subscribed can (www.paytwest.org) and free consulting – including some right here in Colorado programs ask households to sign up for interested communities. – shows that these systems work very for a specific number of containers PAYT (also called variable rates, well in a variety of situations: (or size of wheelie container) as volume-based rates and other names) • Private haulers (Lafayette), multiple their usual garbage service and get provide a different way to bill for garbage haulers (Fort Collins) or city systems a bill that is higher for bigger service. -

Impacts of Pay-As-You-Throw Municipal Solid Waste Collection

City of Milwaukee: Impacts of Pay-As-You-Throw Municipal Solid Waste Collection Prepared by Catherine Hall Gail Krumenauer Kevin Luecke Seth Nowak For the City of Milwaukee, Department of Administration, Budget and Management Division Workshop in Public Affairs, Domestic Issues Public Affairs 869 Spring 2009 Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs University of Wisconsin-Madison ©2009 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. For additional copies: Publications Office La Follette School of Public Affairs 1225 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706 www.lafollette.wisc.edu/publications/workshops.html [email protected] The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs is a nonpartisan teaching and research department of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The school takes no stand on policy issues; opinions expressed in these pages reflect the views of the authors. ii Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures...................................................................................... iv Foreword ................................................................................................................. v Acknowledgments.................................................................................................. vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Research -

Components of a Successful Illegal Dumping Prevention/Enforcement

Building a Successful Illegal Dumping Prevention/Enforcement Program MDEQ’s Solid Waste Enforcement Officer Training March 26-27, 2013 Jackson, MS Building a Successful Illegal Dumping Prevention/Enforcement Program Successful Local Illegal Dumping Programs Are Needed Because: Illegal dumping and Litter repel economic development, investment, and location of businesses; Illegal dumping and Litter decreases property values and increases decay; Decreased tourism in certain communities due to litter and urban blight; Successful Local Illegal Dumping Programs Are Needed Because: Decline in revenue for littered business districts; Increasing costs for cleanup programs requires additional financial resources taken from revenues received by businesses, local governments, taxpayers, and property owners. Successful Local Illegal Dumping Programs Are Needed Because: Related crime activities are more likely to occur in blighted areas (drug deals, prostitution, gang violence, loitering, vandalism, etc.) Litter & illegal dumping are often committed by those wanted for more serious crimes Littered areas indicate lack of concern and loss of local pride in obeying the law Successful Local Illegal Dumping Programs Are Needed Because: Illegal Dumping can interfere with proper drainage and contribute to flooding; Open burning at dumpsites can cause uncontrolled fires damaging forests and private properties; Illegal dumping of some wastes can release contaminants into the air and water (used oil, PCB’s, mercury, asbestos, CFC’s, etc.) Successful -

Guide for Discharging Industrial Wastewater to the Sewer

INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT DIVISION (IWMD) The Industrial Waste Management Division (IWMD) of the Bureau of Sanitation monitors, regulates, and controls industrial wastewater discharges to the City’s wastewater collection and treatment system. MISSION IWMD’s mission is to protect public health and safety, the wastewater system, and the environment by implementing an effective and efficient program for source control of pollutants while enhancing relationships with industry, government, and the public. VISION IWMD’s vision for the future is to set the standard of excellence in source control of pollutants to the wastewater system. TABLE OF CONTENTS OUR ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY………………………………………………………….. 2 DOING YOUR PART…………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 WHO NEEDS AN INDUSTRIAL WASTEWATER PERMIT…………………………………………... 3 HOW TO OBTAIN AN INDUSTRIAL WASTEWATER PERMIT……………………………………...3 INDUSTRIAL WASTE PERMIT REQUIREMENTS AND INDUSTRIAL USER RESPONSIBILITIES……………………………………………………….. 3 DISCHARGE LIMITATIONS AND PROHIBITIONS………………………………………………….. 4 INSPECTION AND SAMPLING………………………………………………………………………… 6 INDUSTRIAL WASTE FEES…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 ENFORCEMENT…………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 POLLUTION PREVENTION…………………………………………………………………………….. 7 HELP IS AVAILABLE……………………………………………………………………………………. 8 REPORTING ILLEGAL DISCHARGES………………………………………………………………… 9 For more than five decades, the Industrial Waste Management Division (IWMD), of the Bureau of Sanitation, Department of Public Works, has worked to protect the local receiving waters (rivers -

Environmental Pollution from Illegal Waste Disposal and Health Effects: a Review on the “Triangle of Death”

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1216-1236; doi:10.3390/ijerph120201216 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Review Environmental Pollution from Illegal Waste Disposal and Health Effects: A Review on the “Triangle of Death” Maria Triassi 1, Rossella Alfano 1, Maddalena Illario 2, Antonio Nardone 1, Oreste Caporale 1 and Paolo Montuori 1,* 1 Department of Public Health, “Federico II” University, Naples 80131, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (O.C.) 2 Department of Traslational Medical Science, “Federico II” University, Naples 80131, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +039-081-746-3027. Academic Editor: Oladele A. Ogunseitan Received: 16 December 2014 / Accepted: 15 January 2015 / Published: 22 January 2015 Abstract: The term “triangle of death” was used for the first time by Senior and Mazza in the journal The Lancet Oncology referring to the eastern area of the Campania Region (Southern Italy) which has one of the worst records of illegal waste dumping practices. In the past decades, many studies have focused on the potential of illegal waste disposal to cause adverse effects on human health in this area. The great heterogeneity in the findings, and the bias in media communication has generated great healthcare doubts, anxieties and alarm. This paper addresses a review of the up-to-date literature on the “triangle of death”, bringing together the available information on the occurrence and severity of health effects related to illegal waste disposal. -

How to Implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) a Briefing For

23 August 2019 How to implement extended producer responsibility (EPR) A briefing for governments and businesses By: Emma Watkins Susanna Gionfra Funded by Disclaimer: The arguments expressed in this report are solely those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinion of any other party. The report should be cited as follows: E. Watkins and S. Gionfra (2019) How to implement extended producer responsibility (EPR): A briefing for governments and businesses Corresponding author: Emma Watkins Acknowledgements: We thank Xin Chen and Annika Lilliestam of WWF Germany for their inputs and comments during the preparation of this briefing. Cover image: Pexels Free Stock Photos Institute for European Environmental Policy AISBL Brussels Office Rue Joseph II 36-38 1000 Bruxelles Belgium Tel: +32 (0) 2738 7482 Fax: +32 (0) 2732 4004 London Office 11 Belgrave Road IEEP Offices, Floor 3 London, SW1V 1RB Tel: +44 (0) 20 7799 2244 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7799 2600 The Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) is an independent not-for-profit institute. IEEP undertakes work for external sponsors in a range of policy areas as well as engaging in our own research programmes. For further information about IEEP, see our website at www.ieep.eu or contact any staff member. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction and context for this briefing .................................................................. 7 2 Introduction to extended -

Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: a Review of Global Issues

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues Navarro Ferronato * and Vincenzo Torretta Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, Via G.B. Vico 46, I-21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-338-887-5813 Received: 6 March 2019; Accepted: 22 March 2019; Published: 24 March 2019 Abstract: Environmental contamination due to solid waste mismanagement is a global issue. Open dumping and open burning are the main implemented waste treatment and final disposal systems, mainly visible in low-income countries. This paper reviews the main impacts due to waste mismanagement in developing countries, focusing on environmental contamination and social issues. The activity of the informal sector in developing cities was also reviewed, focusing on the main health risks due to waste scavenging. Results reported that the environmental impacts are pervasive worldwide: marine litter, air, soil and water contamination, and the direct interaction of waste pickers with hazardous waste are the most important issues. Many reviews were published in the scientific literature about specific waste streams, in order to quantify its effect on the environment. This narrative literature review assessed global issues due to different waste fractions showing how several sources of pollution are affecting the environment, population health, and sustainable development. The results and case studies presented can be of reference for scholars and stakeholders for quantifying the comprehensive impacts and for planning integrated solid waste collection and treatment systems, for improving sustainability at a global level. Keywords: environmental contamination; public health; solid waste management; sustainability; open dumping; informal recycling; open burning; sustainable development; hazardous waste; risk assessment 1. -

Pet Waste Litter, Illegal Dumping, and Illicit Discharges Proper Storage, Application and Disposal

LITTER, ILLEGAL DUMPING, AND PROPER STORAGE, APPLICATION PET WASTE ILLICIT DISCHARGES AND DISPOSAL Why pick up after your pet? True or False? When water enters the storm drain, it Handle chemicals with care. goes to a treatment plant before being released back Myth: My pet is supposed to go outside, it’s just one into a stream or lake. Poorly stored pesticides, cleaners, automotive fluids, animal, let nature take it’s course. and other products have a high probability of running False. Storm drains are designed to drain water away off our yards and driveways and they eventually wind Fact: The number of pets in a concentrated area do- from our homes and streets. Unfortunately, they can up in a creek. ing their business day after day really adds up. It dis- sometimes become receptacles for litter and illegally rupts the natural processes for managing waste and dumped items. Much of the litter and poorly stored Manufacturers threatens the health of humans and other animals. If items end up in local creeks. provide specific not picked up, waste is often washed into local water- Illicit discharges instructions to ways during rain events. Both Beaver Creek and Little include dump- protect health and Creek are vulnerable to bacteria pollution. ing, straight safety. Follow the pipes to a ditch recommendations It starts with you or creek, and to safely apply the irresponsible chemicals. Pet Waste Stations are located in parks adjacent handling of ma- to creeks such as Mumpower Park and Sugar terials. These Hollow Park. activities are Safe Homes and Yards = Safer Creeks Use a bag that is provided or bring your own and illegal and always dispose properly. -

Illegal Dumping

Illegal Dumping Illegal dumping is the improper disposal of waste at from Class 3 landfills in South Carolina and any location other than a permitted landfill or facility. proper disposal takes more time and costs money. It is not only against the law, but illegal dumping also Household garbage and commercial waste also are poses a threat to human health and the environment. illegally dumped because there isn’t adequate service or simply to avoid disposal costs. Also known as open dumping or midnight dumping, illegal dumping usually happens in open areas, If not addressed, illegal dumps often attract more along roadsides, in wooded areas and even in state waste including hazardous household chemicals, parks, and frequently occurs late at night. The waste paint, asbestos and automobile fluids. primarily is non-hazardous material that is dumped to avoid disposal fees or the time and effort required for Where are the materials dumped? proper disposal. The common locations used for illegal dumping often Illegal dumping is a serious issue. include abandoned industrial sites, vacant lots on public or private property and little used roadways or The state can prosecute illegal dumpers through alleyways. Areas along rural roads and railways are the S.C. Litter Control Act and the S.C. Solid Waste particularly vulnerable because of their accessibility Policy and Management Act of 1991. The S.C. and poor lighting. Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) has criminal investigators assigned to Here is an important note to property owners – it is investigate open dumping. Anyone convicted of illegal illegal to allow open dumping on your property. -

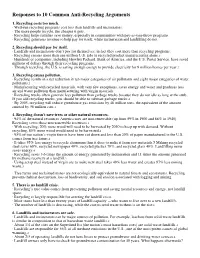

Responses to Common Anti-Recycling Arguments

Responses to 10 Common Anti-Recycling Arguments 1. Recycling costs too much. · Well-run recycling programs cost less than landfills and incinerators. · The more people recycle, the cheaper it gets. · Recycling helps families save money, especially in communities with pay-as-you-throw programs. · Recycling generates revenue to help pay for itself, while incineration and landfilling do not. 2. Recycling should pay for itself. · Landfills and incinerators don’t pay for themselves; in fact they cost more than recycling programs. · Recycling creates more than one million U.S. jobs in recycled product manufacturing alone.1 · Hundreds of companies, including Hewlett Packard, Bank of America, and the U.S. Postal Service, have saved millions of dollars through their recycling programs. · Through recycling, the U.S. is saving enough energy to provide electricity for 9 million homes per year.2 3. Recycling causes pollution. · Recycling results in a net reduction in ten major categories of air pollutants and eight major categories of water pollutants.3 · Manufacturing with recycled materials, with very few exceptions, saves energy and water and produces less air and water pollution than manufacturing with virgin materials. · Recycling trucks often generate less pollution than garbage trucks because they do not idle as long at the curb. If you add recycling trucks, you should be able to subtract garbage trucks.4 · By 2005, recycling will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 48 million tons, the equivalent of the amount emitted by 36 million cars.1 4. Recycling doesn't save trees or other natural resources. · 94% of the natural resources America uses are non-renewable (up from 59% in 1900 and 88% in 1945).