A Genetic Hypothesis for Chiari I Malformation with Or Without Syringomyelia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syndromic Ear Anomalies and Renal Ultrasounds

Syndromic Ear Anomalies and Renal Ultrasounds Raymond Y. Wang, MD*; Dawn L. Earl, RN, CPNP‡; Robert O. Ruder, MD§; and John M. Graham, Jr, MD, ScD‡ ABSTRACT. Objective. Although many pediatricians cific MCA syndromes that have high incidences of renal pursue renal ultrasonography when patients are noted to anomalies. These include CHARGE association, Townes- have external ear malformations, there is much confusion Brocks syndrome, branchio-oto-renal syndrome, Nager over which specific ear malformations do and do not syndrome, Miller syndrome, and diabetic embryopathy. require imaging. The objective of this study was to de- Patients with auricular anomalies should be assessed lineate characteristics of a child with external ear malfor- carefully for accompanying dysmorphic features, includ- mations that suggest a greater risk of renal anomalies. We ing facial asymmetry; colobomas of the lid, iris, and highlight several multiple congenital anomaly (MCA) retina; choanal atresia; jaw hypoplasia; branchial cysts or syndromes that should be considered in a patient who sinuses; cardiac murmurs; distal limb anomalies; and has both ear and renal anomalies. imperforate or anteriorly placed anus. If any of these Methods. Charts of patients who had ear anomalies features are present, then a renal ultrasound is useful not and were seen for clinical genetics evaluations between only in discovering renal anomalies but also in the diag- 1981 and 2000 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los nosis and management of MCA syndromes themselves. Angeles and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in A renal ultrasound should be performed in patients with New Hampshire were reviewed retrospectively. Only pa- isolated preauricular pits, cup ears, or any other ear tients who underwent renal ultrasound were included in anomaly accompanied by 1 or more of the following: the chart review. -

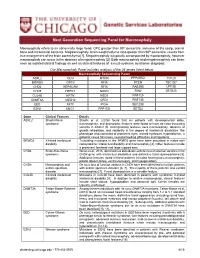

Macrocephaly Information Sheet 6-13-19

Next Generation Sequencing Panel for Macrocephaly Clinical Features: Macrocephaly refers to an abnormally large head, OFC greater than 98th percentile, inclusive of the scalp, cranial bone and intracranial contents. Megalencephaly, brain weight/volume ratio greater than 98th percentile, results from true enlargement of the brain parenchyma [1]. Megalencephaly is typically accompanied by macrocephaly, however macrocephaly can occur in the absence of megalencephaly [2]. Both macrocephaly and megalencephaly can been seen as isolated clinical findings as well as clinical features of a mutli-systemic syndromic diagnosis. Our Macrocephaly Panel includes analysis of the 36 genes listed below. Macrocephaly Sequencing Panel ASXL2 GLI3 MTOR PPP2R5D TCF20 BRWD3 GPC3 NFIA PTEN TBC1D7 CHD4 HEPACAM NFIX RAB39B UPF3B CHD8 HERC1 NONO RIN2 ZBTB20 CUL4B KPTN NSD1 RNF125 DNMT3A MED12 OFD1 RNF135 EED MITF PIGA SEC23B EZH2 MLC1 PPP1CB SETD2 Gene Clinical Features Details ASXL2 Shashi-Pena Shashi et al. (2016) found that six patients with developmental delay, syndrome macrocephaly, and dysmorphic features were found to have de novo truncating variants in ASXL2 [3]. Distinguishing features were macrocephaly, absence of growth retardation, and variability in the degree of intellectual disabilities The phenotype also consisted of prominent eyes, arched eyebrows, hypertelorism, a glabellar nevus flammeus, neonatal feeding difficulties and hypotonia. BRWD3 X-linked intellectual Truncating mutations in the BRWD3 gene have been described in males with disability nonsyndromic intellectual disability and macrocephaly [4]. Other features include a prominent forehead and large cupped ears. CHD4 Sifrim-Hitz-Weiss Weiss et al., 2016, identified five individuals with de novo missense variants in the syndrome CHD4 gene with intellectual disabilities and distinctive facial dysmorphisms [5]. -

Polydactyly of the Hand

A Review Paper Polydactyly of the Hand Katherine C. Faust, MD, Tara Kimbrough, BS, Jean Evans Oakes, MD, J. Ollie Edmunds, MD, and Donald C. Faust, MD cleft lip/palate, and spina bifida. Thumb duplication occurs in Abstract 0.08 to 1.4 per 1000 live births and is more common in Ameri- Polydactyly is considered either the most or second can Indians and Asians than in other races.5,10 It occurs in a most (after syndactyly) common congenital hand ab- male-to-female ratio of 2.5 to 1 and is most often unilateral.5 normality. Polydactyly is not simply a duplication; the Postaxial polydactyly is predominant in black infants; it is most anatomy is abnormal with hypoplastic structures, ab- often inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, if isolated, 1 normally contoured joints, and anomalous tendon and or in an autosomal recessive pattern, if syndromic. A prospec- ligament insertions. There are many ways to classify tive San Diego study of 11,161 newborns found postaxial type polydactyly, and surgical options range from simple B polydactyly in 1 per 531 live births (1 per 143 black infants, excision to complicated bone, ligament, and tendon 1 per 1339 white infants); 76% of cases were bilateral, and 3 realignments. The prevalence of polydactyly makes it 86% had a positive family history. In patients of non-African descent, it is associated with anomalies in other organs. Central important for orthopedic surgeons to understand the duplication is rare and often autosomal dominant.5,10 basic tenets of the abnormality. Genetics and Development As early as 1896, the heritability of polydactyly was noted.11 As olydactyly is the presence of extra digits. -

Familial Poland Anomaly

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.19.4.293 on 1 August 1982. Downloaded from Journal ofMedical Genetics, 1982, 19, 293-296 Familial Poland anomaly T J DAVID From the Department of Child Health, University of Manchester, Booth Hall Children's Hospital, Manchester SUMMARY The Poland anomaly is usually a non-genetic malformation syndrome. This paper reports two second cousins who both had a typical left sided Poland anomaly, and this constitutes the first recorded case of this condition affecting more than one member of a family. Despite this, for the purposes of genetic counselling, the Poland anomaly can be regarded as a sporadic condition with an extremely low recurrence risk. The Poland anomaly comprises congenital unilateral slightly reduced. The hands were normal. Another absence of part of the pectoralis major muscle in son (Greif himself) said that his own left pectoralis combination with a widely varying spectrum of major was weaker than the right. "Although the ipsilateral upper limb defects.'-4 There are, in difference is obvious, the author still had to carry addition, patients with absence of the pectoralis out his military duties"! major in whom the upper limbs are normal, and Trosev and colleagues9 have been widely quoted as much confusion has been caused by the careless reporting familial cases of the Poland anomaly. labelling of this isolated defect as the Poland However, this is untrue. They described a mother anomaly. It is possible that the two disorders are and child with autosomal dominant radial sided part of a single spectrum, though this has never been upper limb defects. -

Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S. Dias, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Thomas Samson, MD, FAAP,b Elias B. Rizk, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Lance S. Governale, MD, FAAP, FAANS,c Joan T. Richtsmeier, PhD,d SECTION ON NEUROLOGIC SURGERY, SECTION ON PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY Pediatric care providers, pediatricians, pediatric subspecialty physicians, and abstract other health care providers should be able to recognize children with abnormal head shapes that occur as a result of both synostotic and aSection of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery and deformational processes. The purpose of this clinical report is to review the bDivision of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of characteristic head shape changes, as well as secondary craniofacial Medicine and dDepartment of Anthropology, College of the Liberal Arts characteristics, that occur in the setting of the various primary and Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania; and cLillian S. Wells Department of craniosynostoses and deformations. As an introduction, the physiology and Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, genetics of skull growth as well as the pathophysiology underlying Florida craniosynostosis are reviewed. This is followed by a description of each type of Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from primary craniosynostosis (metopic, unicoronal, bicoronal, sagittal, lambdoid, expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of and frontosphenoidal) and their resultant head shape changes, with an Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the emphasis on differentiating conditions that require surgical correction from organizations or government agencies that they represent. -

Haploinsufficiency of BMP4 and OTX2 in the Foetus with an Abnormal

Capkova et al. Molecular Cytogenetics (2017) 10:47 DOI 10.1186/s13039-017-0351-3 CASEREPORT Open Access Haploinsufficiency of BMP4 and OTX2 in the Foetus with an abnormal facial profile detected in the first trimester of pregnancy Pavlina Capkova1* , Alena Santava1, Ivana Markova2, Andrea Stefekova1, Josef Srovnal3, Katerina Staffova3 and Veronika Durdová2 Abstract Background: Interstitial microdeletion 14q22q23 is a rare chromosomal syndrome associated with variable defects: microphthalmia/anophthalmia, pituitary anomalies, polydactyly/syndactyly of hands and feet, micrognathia/ retrognathia. The reports of the microdeletion 14q22q23 detected in the prenatal stages are limited and the range of clinical features reveals a quite high variability. Case presentation: We report a detection of the microdeletion 14q22.1q23.1 spanning 7,7 Mb and involving the genes BMP4 and OTX2 in the foetus by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) and verified by microarray subsequently. The pregnancy was referred to the genetic counselling for abnormal facial profile observed in the first trimester ultrasound scan and micrognathia (suspicion of Pierre Robin sequence), hypoplasia nasal bone and polydactyly in the second trimester ultrasound scan. The pregnancy was terminated on request of the parents. Conclusion: An abnormal facial profile detected on prenatal scan can provide a clue to the presence of rare chromosomal abnormalities in the first trimester of pregnancy despite the normal result of the first trimester screening test. The patients should be provided with genetic counselling. Usage of quick and sensitive methods (MLPA, microarray) is preferable for discovering a causal aberration because some of the CNVs cannot be detected with conventional karyotyping in these cases. -

Syndromes Affecting Ear Nose & Throat

Journal of Analytical & Pharmaceutical Research Syndromes Affecting Ear Nose & Throat Keywords: Throat Review Article genetic disorders; oral manifestations; Ear, Nose, Abbreviations: Volume 5 Issue 4 - 2017 TCS: Treacher Collins Syndrome; RHS: Ramsay Hunt Syndrome; FNP: Facial Nerve Palsy; CHD: Congenital Heart Diseases; AD: Alzheimer’s Diseases; HD: Hirschprung Disease; DS: Down Syndrome; ES: Eagle’s Syndrome; OAV: Department of oral pathology and microbiology, Rajiv Gandhi Oculo-Auriculovertebral; VZV: Varicella Zoster Virus; MPS: University of Health Sciences, India Myofacial Pain Syndrome; FMS: Fibromyalgia Syndrome; NF2: *Corresponding author: Kalpajyoti Bhattacharjee, IntroductionNeurofibromatosis Type I Department of oral pathology and microbiology, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Rajarajeswari Dental College The term syndrome denotes set of signs and symptoms that Email: disease or an increased chance of developing to a particular and Hospital, Bangalore, India, Tel: 8951714933; disease.tend to occurThere together are more and thanreflect 4,000 the presencegenetic disordersof a particular that Received: | Published: constitute head and neck syndromes of which more than 300 May 09, 2017 July 13, 2017 entities involve craniofacial structures [1]. The heritage of the term syndrome is ancient and derived from the Greek word sundrome: sun, syn – together + dromos, a running i.e., “run together”, as the features do. There are of mutated cell are confined to one site and leads to formation of numerous syndromes which involve Ear, Nose, Throat areas with Listmonostotic of Syndromes fibrous dysplasia Affecting [2]. Ear Nose & Throat oral manifestations. The aim of this review is to discuss ear, nose a. Goldenhar syndrome, and throat related syndromes with oral manifestations. b. Frey syndrome, Etiopathogenesis c. -

REVIEW ARTICLE Genetic Disorders of the Skeleton: a Developmental Approach

Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73:447–474, 2003 REVIEW ARTICLE Genetic Disorders of the Skeleton: A Developmental Approach Uwe Kornak and Stefan Mundlos Institute for Medical Genetics, Charite´ University Hospital, Campus Virchow, Berlin Although disorders of the skeleton are individually rare, they are of clinical relevance because of their overall frequency. Many attempts have been made in the past to identify disease groups in order to facilitate diagnosis and to draw conclusions about possible underlying pathomechanisms. Traditionally, skeletal disorders have been subdivided into dysostoses, defined as malformations of individual bones or groups of bones, and osteochondro- dysplasias, defined as developmental disorders of chondro-osseous tissue. In light of the recent advances in molecular genetics, however, many phenotypically similar skeletal diseases comprising the classical categories turned out not to be based on defects in common genes or physiological pathways. In this article, we present a classification based on a combination of molecular pathology and embryology, taking into account the importance of development for the understanding of bone diseases. Introduction grouping of conditions that have a common molecular origin but that have little in common clinically. For ex- Genetic disorders affecting the skeleton comprise a large ample, mutations in COL2A1 can result in such diverse group of clinically distinct and genetically heterogeneous conditions as lethal achondrogenesis type II and Stickler conditions. Clinical manifestations range from neonatal dysplasia, which is characterized by moderate growth lethality to only mild growth retardation. Although they retardation, arthropathy, and eye disease. It is now be- are individually rare, disorders of the skeleton are of coming increasingly clear that several distinct classifi- clinical relevance because of their overall frequency. -

Metopic and Sagittal Synostosis in Greig Cephalopolysyndactyly Syndrome: five Cases with Intragenic Mutations Or Complete Deletions of GLI3

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 757–762 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/11 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Metopic and sagittal synostosis in Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome: five cases with intragenic mutations or complete deletions of GLI3 Jane A Hurst1,2, Dagan Jenkins3, Pradeep C Vasudevan4, Maria Kirchhoff5, Flemming Skovby5, Claudine Rieubland6, Sabina Gallati6, Olaf Rittinger7, Peter M Kroisel8, David Johnson2, Leslie G Biesecker9 and Andrew OM Wilkie*,1,2,3 Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS) is a multiple congenital malformation characterised by limb and craniofacial anomalies, caused by heterozygous mutation or deletion of GLI3. We report four boys and a girl who were presented with trigonocephaly due to metopic synostosis, in association with pre- and post-axial polydactyly and cutaneous syndactyly of hands and feet. Two cases had additional sagittal synostosis. None had a family history of similar features. In all five children, the diagnosis of GCPS was confirmed by molecular analysis of GLI3 (two had intragenic mutations and three had complete gene deletions detected on array comparative genomic hybridisation), thus highlighting the importance of trigonocephaly or overt metopic or sagittal synostosis as a distinct presenting feature of GCPS. These observations confirm and extend a recently proposed association of intragenic GLI3 mutations with metopic synostosis; moreover, the three individuals with complete deletion of GLI3 were previously considered to have Carpenter syndrome, highlighting an important source of diagnostic confusion. European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 757–762; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.13; published online 16 February 2011 Keywords: trigonocephaly; metopic synostosis; sagittal synostosis; Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome; GLI3; Carpenter syndrome INTRODUCTION (SHH) pathway. -

Polydactyly and Brachymetapody in Two English Families SARAH B

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.12.4.355 on 1 December 1975. Downloaded from Journal of Medical Genetics (1975). 12, 355. Polydactyly and brachymetapody in two English families SARAH B. HOLT Galton Laboratory, University College, London Summary. Two new pedigrees of polydactyly associated with brachymeta- pody are described. In one the two defects occur in different members of the family, while in the other both occur in the same individuals. Both anomalies appear to be inherited as dominants, the polydactyly showing incomplete manifes- tation. Polydactyly, the presence of extra digits on though brachymetapody may be combined with hands and feet, is a well-known structural anomaly. brachyphalangy (see for example Birkenfeld, 1928; In man it is presumably due to a dominant gene. Brailsford, 1945). The expression is variable and normal overlapping During the past 70 years brachymetapody has occurs. Relatively frequently persons carrying the been described on numerous occasions, though it gene show no visible abnormality. Both hands and seems to be comparatively uncommon. A number feet may have extra digits, but sometimes not all the of the descriptions are of isolated cases where noth- extremities are affected and in some cases only one ing has been ascertained about the members of the copyright. is abnormal. The defect varies considerably from families concerned. Various pedigrees, however, family to family. Lewis (1909) wrote that poly- have been recorded. Bell (1951), who called the dactyly 'is most frequently post-axial (towards little condition Type E brachydactyly, presented 15 finger or toe), but many varieties are known. Thus pedigrees of brachymetapody from the literature. -

EUROCAT Syndrome Guide

JRC - Central Registry european surveillance of congenital anomalies EUROCAT Syndrome Guide Definition and Coding of Syndromes Version July 2017 Revised in 2016 by Ingeborg Barisic, approved by the Coding & Classification Committee in 2017: Ester Garne, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Jorieke Bergman and Ingeborg Barisic Revised 2008 by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk and Ester Garne and discussed and approved by the Coding & Classification Committee 2008: Elisa Calzolari, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Ingeborg Barisic, Ester Garne The list of syndromes contained in the previous EUROCAT “Guide to the Coding of Eponyms and Syndromes” (Josephine Weatherall, 1979) was revised by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk, Ester Garne, Claude Stoll and Diana Wellesley at a meeting in London in November 2003. Approved by the members EUROCAT Coding & Classification Committee 2004: Ingeborg Barisic, Elisa Calzolari, Ester Garne, Annukka Ritvanen, Claude Stoll, Diana Wellesley 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Definitions 6 Coding Notes and Explanation of Guide 10 List of conditions to be coded in the syndrome field 13 List of conditions which should not be coded as syndromes 14 Syndromes – monogenic or unknown etiology Aarskog syndrome 18 Acrocephalopolysyndactyly (all types) 19 Alagille syndrome 20 Alport syndrome 21 Angelman syndrome 22 Aniridia-Wilms tumor syndrome, WAGR 23 Apert syndrome 24 Bardet-Biedl syndrome 25 Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (EMG syndrome) 26 Blepharophimosis-ptosis syndrome 28 Branchiootorenal syndrome (Melnick-Fraser syndrome) 29 CHARGE -

Congenital Limb Differences

FACT SHEET Congenital Limb Differences Introduction Body parts and limb difference terminology A congenital limb difference means that a baby is born with part or all of a limb missing. It occurs You may hear healthcare providers use a variety of because the limb doesn’t form completely during words to describe parts of your child’s body or their pregnancy. specific limb difference. You may hear that your child’s congenital limb difference: A congenital limb difference can sometimes be identified when you have your pregnancy scans, but • Affects their digits or rays (fingers or toes) other times it is not discovered until after a baby is • Affects their upper limb (arm/hand) and/or lower born. If you have just learned that your child has a limb (leg/foot) limb difference you might be feeling scared, worried • Are unilateral (affects one side) or bilateral (affects or overwhelmed. This is normal. Your child will two sides) find their own way of completing and participating • Are longitudinal, meaning a long bone or part of a in everyday activities, as well as doing some long bone is missing extraordinary things as well. • Are transverse, meaning that a limb does not develop beyond a certain level and will appear as if This fact sheet describes some common it has been taken off. congenital limb differences. Medical terminology for limb difference has changed in recent years, so The Limbs 4 Kids website provides brief definitions throughout this fact sheet we are using the most up- of a wide range of words related to limb difference - to-date medical terms alongside older ones that you limbs4kids.org.au/about-limb-difference may still come across on the internet.