PLYWOOD MALLET.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metalwork & Woodwork Saws

HAMMERS - ANVILS - METALWORK & WOODWORK SAWS C HAMMERS BENCH PIN & ANVIL 77 CABLE TACKER GUN 76 DAVID USE PHOTO COPING SAWS 79 SD0010 FRETSAW BLADES 79 FRETSAW FRAMES 79 O HAMMER S & MALLETS 72 - 74 HACKSAWS 76 - 77 MINITURE ANVILS 74 MINITURE PINS 75 MALLET MITRE BOXES 82 PIERCING SAW BLADES 78 PIERCING SAW FRAMES 78 N DAVID USE PHOTO PIN PUSHERS 75 SD0010 RAZOR SAWS 81 SAW BLADE LUBRICANT 78 SAW KNIFE BLADES 81 STAPLE GUNS 75 - 76 V-BLOCK & CLAMPS 77 WEB STRETCHER 82 T ANVILS WOOD SAWS 80 - 81 X-ACTO RAZOR SAWS 81 DAVID USE PHOTO ZONA RAZOR SAWS 79 SD0010 E SAWS N DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 T V BLOCK & CLAMP DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 S Last Revised 04/07/2011 71 SQUIRES MODEL & CRAFT TOOLS HAMMERS & MALLETS MAGNETIC TACK HAMMER 6oz a specially designed hammer having one striking face magnetised for use when fitting small nails JEWELLERS MALLET a lightweight stainless steel mallet similar and upholstery tacks. The head features a claw for removing to those used by watchmakers and jewellers, with a solid head and tacks, the striking surface is a magnetic split pattern. The head is knurled shaft. hardened and pol- Length 145mm. ished. Fitted on a Weight 2½oz. hickory handle. Weight 6oz, length overall CODE TYPE PRICE 265mm. HA0025 Jewellers Mallet.................................................... £3.99 WATCHMAKERS MALLET a lightweight jewellers and watch- CODE TYPE PRICE makers mallet with a solid brass head. The handle is 260mm long 051-006 Magnetic Tack Hammer 6oz................................. £14.99 and has an increased diameter and is knurled for extra grip. -

Pad Foot Slipper Foot

PAD FOOT SLIPPER FOOT The most familiar foot of the To me, the slipper foot is the three, the pad foot has plenty most successful design for of variations. In the simplest the bottom of a cabriole leg, and most common version the especially when the arrises 3 rim of the foot is ⁄4 in. to 1 in. on the leg are retained and off the floor and its diameter gracefully end at the point is just under the size of the of the foot. There’s a blend leg blank. A competent 18th- of soft curves and defined century turner easily could edges that just works. This have produced it in less than particular foot design was 5 minutes, perhaps explaining taken from a Newport tea its prevalence. This is my table in the Pendleton House interpretation of a typical New collection at the Rhode Island England pad foot. School of Design Museum. 48 FINE WOODWORKING W270BR.indd 48 7/3/18 10:24 AM A step-by-step guide to creating three distinct period feet for the cabriole leg BY STEVE BROWN One Leg, Three Feet n the furniture making program at North Bennet Street School, students usually find inspiration for Itheir projects in books from our extensive library. They’ll find many examples of period pieces, but SLIPPER FOOT TRIFID FOOT they’ll also find more contemporary work. What they won’t find is any lack of possibilities. Sometimes limit- To me, the slipper foot is the The trifid foot is similar to the ing their options is the hard part. -

For Vibraphone and Electronics Written for SPLICE Institute and Shaun Cayabyab

Nathaniel Haering for vibraphone and electronics written for SPLICE Institute and Shaun Cayabyab Resplendent Shards Performance Notes -Accidentals do not carry through un-metered measures -If a specific duration is not shown in a free time section, the rubato pacing is completely at the discretion of the performer. -Assume feather pedaling when specific instructions are not given -Requires 4 average cord vibraphone mallets with rattan handle, a Bass Bow, and a hard mallet for pitch bending. Malletech Bob Becker BB34 suggested for pitch bending. -Piece begins with 4 mallet stevens grip, transitions to holding bow in right hand and a cord medium hard rubber mallet in the 1st and 2nd positions respectively. The piece ends with a return to normal 4 mallet grip. -Arrows suggests a smooth and incredibly slow transition from one technique to another. This is used to show movement from dampened to open pedaling over the approximate space shown and to move on to and off of nodes on pitches marked with a dot inside a hollow note. When traditional pedaling is implied the notation “Ped” will be used. -Downward arrows require the performer to use the hard mallet to add density to the bar and move from the center node outward to lower the pitch -Up bow symbol alongside a staccato and accent asks that the bow be pulled quickly and viciously across the bar. At peak volume, stop with the hairs of the bow remaining in contact with the bar to instantly halt the sound. This creates a loud staccato burst with no residual resonance -Down bows suggest traditional bowing, allowing the note to resonate naturally -Notes with Plus Signs accompanying them suggest dead strokes; notes dampened upon hit with the mallet. -

Luscombe, Philip (2017) What's a Mallet For: a Woodworker's Critique of the Workmanship of Risk

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Luscombe, Philip (2017) What's A Mallet For: A Woodworker's Critique of The Workmanship of Risk. In: RTD2017 - Research Through Design Conference 2017, 22nd - 24th March 2017, Scotland, UK. URL: https://figshare.com/articles/What_s_A_Mallet_For_... <https://figshare.com/articles/What_s_A_Mallet_For_A_Woodworker_s_Critique_of_The_Wo rkmanship_of_Risk/4746922> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/35344/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Research Through Design Conference What’s A Mallet For: A Woodworker’s Critique of The Workmanship of Risk Philip Luscombe Luscombe, P. -

SIMPLEX Splitting Axe• Thin Shape, with Cast Iron Housing and Hickory

Forestry Tools SIMPLEX splitting axe SIMPLEX splitting axe • thin shape, with cast iron housing and hickory handle 3007.750 Product Description Combining two tools into one, a splitting axe and a soft-face mallet of the highest professional quality, Halder's SIMPLEX splitting axes offer a significant savings in cost compared to the individual purchases of the tools. The top-tier quality of the product has been confirmed by the committee for forestry work and forestry technology (KWF). The drop-forged and hardened axe blade is ground and polished. Its slender shape makes it ideal for splitting coniferous wood. The leather cutting protection prevents injury during transport. The superplastic insert with D50mm is a medium hard plastic insert made of extruded and extremely homogeneous material. Compared to injection moulded plastic inserts, it is therefore considerably more wear-resistant and durable. Using the soft side when wedging the wood open entirely eliminates the risk of injury from metal splinters. What is more, the service life of plastic and aluminium wedges is extended substantially. Made of cast iron, the housing comes with an integrated handle protection sleeve that provides for a high level of break resistance. The long-fibre and ultra durable hickory handle is varnished and shaped ergonomically. The total weight is 2,700g. In line with the smart SIMPLEX principle, all components are replaceable and can be retrofitted. This translates to savings in both money and resources. Product features: • 2 tools in 1: Splitting axe plus soft-face mallet, considerably less costly than buying the tools individually. • The drop-forged axe blade with its thin shape is ideal for splitting coniferous wood. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

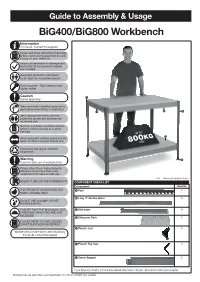

Big400/Big800 Workbench Assembly Instructions

Guide to Assembly & Usage If in doubt please Caution! Warning BiG400/BiG800Caution! Warning Workbench If in doubt please Ifcontact in doubt your please Caution!During assembly Warning contact your Caution!During assembly Warning contactIfsupplier in doubt your please Caution!During assembly Warning supplierIf in doubt please During assembly suppliercontact your During assembly Informationsuppliercontact your Ifsupplier in doubt, contact the supplier Please read Take care when Never climb on the structure Please read Takehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure Pleasethese instructions read Take care when Never climb on the structure these instructions Takehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure PleasethesePlease instructions read read these instructions thoroughlyTakehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure thesePlease instructions read handling heavy objects beforethese instructions commencing assembly & retainhandling heavy objects a Inspectcopy all for packages your reference Inspect all packages Wear appropriate Do no lean ladders, Inspectfor damage all packages and check Wear appropriate Do no lean ladders, Inspectfor damage all packages and check Wearclothing, appropriate protective Dosteps no or lean other ladders, InspectInspectforthat damage all theall packages componentsall and packagescheck ordered for damage Wearclothing, andgloves appropriate and protective footwear Dosteps no or lean other ladders, forthat damage all the components and check ordered Wearclothing, -

Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It to Work Turn a Hook and Watch the Shavings fl Y by Andy Rae

Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It To Work Turn a hook and watch the shavings fl y By Andy Rae When smoothing wood, I reach for a rectangle of steel called a card scraper. Despite its humble appearance, a card scraper is remarkably versatile remove hardened glue, smooth at re�ining surfaces. It will exposed joints, and smooth and level dif�icult woods and it more maneuverable than a planea �inish. for Its reaching small size into makes tight spots, so you can preserve your supply of sandpaper. A scraper does it better, faster and without annoying dust. Scrapers come in all sorts beof shapesused in and specially sizes, includingdesigned planescurved and and scraper pro�iled. holders. Some can But my daily scraper is the card scraper, either thin (0.020- 0.025") or thick (0.30-.0.040") depending on the job at hand. Thinner scrapers excel at delicate work, where light cuts and 24 woodcraftmagazine.com Oct/Nov 2015 Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It To Work Scraper job descripti on scrapers are best for heavier work:�inesse smoothing are required. tabletops, Thicker removing milling marks, and the like. For most applications, the scraping work is done by a small hook along the working edge. With a little practice, you can use this tool to produce tiny shavings, even on hard and when worked with a plane. �igured woods that show tearout Smoothing fi gured wood is Leveling between coats enables to work properly, and I’ll show the perfect scraper assignment you to remove drips and other youScrapers how this require can be sharpening done with a because planing the workpiece surface irregulariti es in order to few basic tools. -

Assembly Instructions 4' Workbench

FIGURE 9 L ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS 4’ WORKBENCH Model: 01048 STEP 16 Align the drawer glides on the drawer assembly to the drawer mount glides and carefully slide in. Pull the drawer in and out making sure the glides are locked together. STEP 17 Place 5/8” shelf (L) into place. Congratulations! The assembly is complete. For assembly assistance call 800-495-9278 2805 Fairview Ave. North Weekdays: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Central Time Roseville, MN 55113 4’ Workbench Manual Revised 12-08 Thank You for purchasing a high quality workbench from Decko Products. If you require any FIGURE 8 assistance with assembly, please contact us toll free at 1-800-495-9278. FIGURE 7 Monday through Friday 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Central Time. B Tools Needed J • Rubber Mallet or hammer. E Assembly Tips K P • Fully read and understand these instructions before starting assembly. G • Group similar parts together. • If the use of a mallet or hammer is required, use a block or cloth to protect the finish. F • Assemble the workbench on a sturdy surface. D • Make sure the rivets seat fully in the bottom of the keyhole slots. B Do’s and Don’ts E • Do not overload the shelves and/or drawer. • Store smaller, lighter items on the top shelf and larger, heavier items on the bottom shelf. • Do not store the workbench outdoors. • It’s highly recommended to seal or paint the wood shelves when they are exposed to humid environments or when they will be subject to grease, oil or moisture contact. -

T30069 CP Hand Tool Instruction Manual

Instruction T30069 Manual CP Hand Tool Introduction: The T30069 Center Punch Tool installs BAND-IT 3/8" and 5/8", 201 Stainless Steel and Galvanized Carbon Steel clamps. Table of Contents: 1. Introduction & Safety Practices 2. Operating Instructions 3. Tool Assembly 4. Repair Parts List 5. 3/8" Adapter & Warranty Safety Practices: 1. Read this manual and become familiar with the tool before use. 2. Protective eyewear should be worn during use. 3. Wear appropriate gloves for handling steel. 4. When applying clamps, care should be taken to insure fingers are not in contact with the clamp during installation. 5. Never attempt to clamp objects which have the potential to burst, shatter or otherwise cause bodily harm. 6. Do not use tool on live electrical sources. BAND-IT IDEX, Inc. Document # P15087 rev. J A Unit of IDEX Corporation © Copyright 4799 Dahlia Street www.BAND-IT-IDEX.com BAND-IT IDEX, Inc. 2013 Denver, CO 80216-0307 USA All rights reserved P: 1-800-525-0758 Page 1 of 5 F: 1-800-624-3925 Operating T30069 Instructions CP Hand Tool 1 FORWARD POSITION OR “OPEN” 2 SLIDE TIGHTEN CLAMP Tighten the clamp with short downward strokes. Tension LOAD CLAMP handle should be in down position at completion of Push tension handle all the way forward. Insert tightening clamp. BAND-IT Center Punch clamp tail and push all the Note: Do not lift tension handle too high as it may open up way into tool. buckle pusher, resulting in improper clamp application. Tool Tip: To apply 3/8” wide clamps, use S03289 If clamp tension needs to be released before locking, move adapter kit. -

Extended Performance Techniques and Compositional Style in the Solo

EXTENDED PERFORMANCE TECHNIQUES AND COMPOSITIONAL STYLE IN THE SOLO CONCERT VIBRAPHONE MUSIC OF CHRISTOPHER DEANE Joshua D. Smith, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2008 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Christopher Deane, Committee Member Terri Sundberg, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Smith, Joshua D., Extended performance techniques and compositional style in the solo concert vibraphone music of Christopher Deane. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2008, 66 pp., 1 table, 8 figures, 20 musical examples, references, 29 titles. Vibraphone performance continues to be an expanding field of music. Earliest accounts of the presence of the vibraphone and vibraphone players can be found in American Vaudeville from the early 1900s; then found shortly thereafter in jazz bands as early as the 1930s, and on the classical concert stage beginning in 1949. Three Pieces for Vibraphone, Opus 27, composed by James Beale in 1959, is the first solo concert piece written exclusively for the instrument. Since 1959, there have been over 690 pieces written for solo concert vibraphone, which stands as evidence of the popularity of both the instrument and the genre of solo concert literature. Christopher Deane has contributed to solo vibraphone repertoire with works that are regarded as staples in the genre. Deane’s compositions for vibraphone consistently expand the technical and musical potential of the instrument. -

Woodworking Glossary, a Comprehensive List of Woodworking Terms and Their Definitions That Will Help You Understand More About Woodworking

Welcome to the Woodworking Glossary, a comprehensive list of woodworking terms and their definitions that will help you understand more about woodworking. Each word has a complete definition, and several have links to other pages that further explain the term. Enjoy. Woodworking Glossary A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | #'s | A | A-Frame This is a common and strong building and construction shape where you place two side pieces in the orientation of the legs of a letter "A" shape, and then cross brace the middle. This is useful on project ends, and bases where strength is needed. Abrasive Abrasive is a term use to describe sandpaper typically. This is a material that grinds or abrades material, most commonly wood, to change the surface texture. Using Abrasive papers means using sandpaper in most cases, and you can use it on wood, or on a finish in between coats or for leveling. Absolute Humidity The absolute humidity of the air is a measurement of the amount of water that is in the air. This is without regard to the temperature, and is a measure of how much water vapor is being held in the surrounding air. Acetone Acetone is a solvent that you can use to clean parts, or remove grease. Acetone is useful for removing and cutting grease on a wooden bench top that has become contaminated with oil. Across the Grain When looking at the grain of a piece of wood, if you were to scratch the piece perpendicular to the direction of the grain, this would be an across the grain scratch.