Luscombe, Philip (2017) What's a Mallet For: a Woodworker's Critique of the Workmanship of Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metalwork & Woodwork Saws

HAMMERS - ANVILS - METALWORK & WOODWORK SAWS C HAMMERS BENCH PIN & ANVIL 77 CABLE TACKER GUN 76 DAVID USE PHOTO COPING SAWS 79 SD0010 FRETSAW BLADES 79 FRETSAW FRAMES 79 O HAMMER S & MALLETS 72 - 74 HACKSAWS 76 - 77 MINITURE ANVILS 74 MINITURE PINS 75 MALLET MITRE BOXES 82 PIERCING SAW BLADES 78 PIERCING SAW FRAMES 78 N DAVID USE PHOTO PIN PUSHERS 75 SD0010 RAZOR SAWS 81 SAW BLADE LUBRICANT 78 SAW KNIFE BLADES 81 STAPLE GUNS 75 - 76 V-BLOCK & CLAMPS 77 WEB STRETCHER 82 T ANVILS WOOD SAWS 80 - 81 X-ACTO RAZOR SAWS 81 DAVID USE PHOTO ZONA RAZOR SAWS 79 SD0010 E SAWS N DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 T V BLOCK & CLAMP DAVID USE PHOTO SD0010 S Last Revised 04/07/2011 71 SQUIRES MODEL & CRAFT TOOLS HAMMERS & MALLETS MAGNETIC TACK HAMMER 6oz a specially designed hammer having one striking face magnetised for use when fitting small nails JEWELLERS MALLET a lightweight stainless steel mallet similar and upholstery tacks. The head features a claw for removing to those used by watchmakers and jewellers, with a solid head and tacks, the striking surface is a magnetic split pattern. The head is knurled shaft. hardened and pol- Length 145mm. ished. Fitted on a Weight 2½oz. hickory handle. Weight 6oz, length overall CODE TYPE PRICE 265mm. HA0025 Jewellers Mallet.................................................... £3.99 WATCHMAKERS MALLET a lightweight jewellers and watch- CODE TYPE PRICE makers mallet with a solid brass head. The handle is 260mm long 051-006 Magnetic Tack Hammer 6oz................................. £14.99 and has an increased diameter and is knurled for extra grip. -

For Vibraphone and Electronics Written for SPLICE Institute and Shaun Cayabyab

Nathaniel Haering for vibraphone and electronics written for SPLICE Institute and Shaun Cayabyab Resplendent Shards Performance Notes -Accidentals do not carry through un-metered measures -If a specific duration is not shown in a free time section, the rubato pacing is completely at the discretion of the performer. -Assume feather pedaling when specific instructions are not given -Requires 4 average cord vibraphone mallets with rattan handle, a Bass Bow, and a hard mallet for pitch bending. Malletech Bob Becker BB34 suggested for pitch bending. -Piece begins with 4 mallet stevens grip, transitions to holding bow in right hand and a cord medium hard rubber mallet in the 1st and 2nd positions respectively. The piece ends with a return to normal 4 mallet grip. -Arrows suggests a smooth and incredibly slow transition from one technique to another. This is used to show movement from dampened to open pedaling over the approximate space shown and to move on to and off of nodes on pitches marked with a dot inside a hollow note. When traditional pedaling is implied the notation “Ped” will be used. -Downward arrows require the performer to use the hard mallet to add density to the bar and move from the center node outward to lower the pitch -Up bow symbol alongside a staccato and accent asks that the bow be pulled quickly and viciously across the bar. At peak volume, stop with the hairs of the bow remaining in contact with the bar to instantly halt the sound. This creates a loud staccato burst with no residual resonance -Down bows suggest traditional bowing, allowing the note to resonate naturally -Notes with Plus Signs accompanying them suggest dead strokes; notes dampened upon hit with the mallet. -

SIMPLEX Splitting Axe• Thin Shape, with Cast Iron Housing and Hickory

Forestry Tools SIMPLEX splitting axe SIMPLEX splitting axe • thin shape, with cast iron housing and hickory handle 3007.750 Product Description Combining two tools into one, a splitting axe and a soft-face mallet of the highest professional quality, Halder's SIMPLEX splitting axes offer a significant savings in cost compared to the individual purchases of the tools. The top-tier quality of the product has been confirmed by the committee for forestry work and forestry technology (KWF). The drop-forged and hardened axe blade is ground and polished. Its slender shape makes it ideal for splitting coniferous wood. The leather cutting protection prevents injury during transport. The superplastic insert with D50mm is a medium hard plastic insert made of extruded and extremely homogeneous material. Compared to injection moulded plastic inserts, it is therefore considerably more wear-resistant and durable. Using the soft side when wedging the wood open entirely eliminates the risk of injury from metal splinters. What is more, the service life of plastic and aluminium wedges is extended substantially. Made of cast iron, the housing comes with an integrated handle protection sleeve that provides for a high level of break resistance. The long-fibre and ultra durable hickory handle is varnished and shaped ergonomically. The total weight is 2,700g. In line with the smart SIMPLEX principle, all components are replaceable and can be retrofitted. This translates to savings in both money and resources. Product features: • 2 tools in 1: Splitting axe plus soft-face mallet, considerably less costly than buying the tools individually. • The drop-forged axe blade with its thin shape is ideal for splitting coniferous wood. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Big400/Big800 Workbench Assembly Instructions

Guide to Assembly & Usage If in doubt please Caution! Warning BiG400/BiG800Caution! Warning Workbench If in doubt please Ifcontact in doubt your please Caution!During assembly Warning contact your Caution!During assembly Warning contactIfsupplier in doubt your please Caution!During assembly Warning supplierIf in doubt please During assembly suppliercontact your During assembly Informationsuppliercontact your Ifsupplier in doubt, contact the supplier Please read Take care when Never climb on the structure Please read Takehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure Pleasethese instructions read Take care when Never climb on the structure these instructions Takehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure PleasethesePlease instructions read read these instructions thoroughlyTakehandling care heavywhen objects Never climb on the structure thesePlease instructions read handling heavy objects beforethese instructions commencing assembly & retainhandling heavy objects a Inspectcopy all for packages your reference Inspect all packages Wear appropriate Do no lean ladders, Inspectfor damage all packages and check Wear appropriate Do no lean ladders, Inspectfor damage all packages and check Wearclothing, appropriate protective Dosteps no or lean other ladders, InspectInspectforthat damage all theall packages componentsall and packagescheck ordered for damage Wearclothing, andgloves appropriate and protective footwear Dosteps no or lean other ladders, forthat damage all the components and check ordered Wearclothing, -

Assembly Instructions 4' Workbench

FIGURE 9 L ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS 4’ WORKBENCH Model: 01048 STEP 16 Align the drawer glides on the drawer assembly to the drawer mount glides and carefully slide in. Pull the drawer in and out making sure the glides are locked together. STEP 17 Place 5/8” shelf (L) into place. Congratulations! The assembly is complete. For assembly assistance call 800-495-9278 2805 Fairview Ave. North Weekdays: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Central Time Roseville, MN 55113 4’ Workbench Manual Revised 12-08 Thank You for purchasing a high quality workbench from Decko Products. If you require any FIGURE 8 assistance with assembly, please contact us toll free at 1-800-495-9278. FIGURE 7 Monday through Friday 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Central Time. B Tools Needed J • Rubber Mallet or hammer. E Assembly Tips K P • Fully read and understand these instructions before starting assembly. G • Group similar parts together. • If the use of a mallet or hammer is required, use a block or cloth to protect the finish. F • Assemble the workbench on a sturdy surface. D • Make sure the rivets seat fully in the bottom of the keyhole slots. B Do’s and Don’ts E • Do not overload the shelves and/or drawer. • Store smaller, lighter items on the top shelf and larger, heavier items on the bottom shelf. • Do not store the workbench outdoors. • It’s highly recommended to seal or paint the wood shelves when they are exposed to humid environments or when they will be subject to grease, oil or moisture contact. -

T30069 CP Hand Tool Instruction Manual

Instruction T30069 Manual CP Hand Tool Introduction: The T30069 Center Punch Tool installs BAND-IT 3/8" and 5/8", 201 Stainless Steel and Galvanized Carbon Steel clamps. Table of Contents: 1. Introduction & Safety Practices 2. Operating Instructions 3. Tool Assembly 4. Repair Parts List 5. 3/8" Adapter & Warranty Safety Practices: 1. Read this manual and become familiar with the tool before use. 2. Protective eyewear should be worn during use. 3. Wear appropriate gloves for handling steel. 4. When applying clamps, care should be taken to insure fingers are not in contact with the clamp during installation. 5. Never attempt to clamp objects which have the potential to burst, shatter or otherwise cause bodily harm. 6. Do not use tool on live electrical sources. BAND-IT IDEX, Inc. Document # P15087 rev. J A Unit of IDEX Corporation © Copyright 4799 Dahlia Street www.BAND-IT-IDEX.com BAND-IT IDEX, Inc. 2013 Denver, CO 80216-0307 USA All rights reserved P: 1-800-525-0758 Page 1 of 5 F: 1-800-624-3925 Operating T30069 Instructions CP Hand Tool 1 FORWARD POSITION OR “OPEN” 2 SLIDE TIGHTEN CLAMP Tighten the clamp with short downward strokes. Tension LOAD CLAMP handle should be in down position at completion of Push tension handle all the way forward. Insert tightening clamp. BAND-IT Center Punch clamp tail and push all the Note: Do not lift tension handle too high as it may open up way into tool. buckle pusher, resulting in improper clamp application. Tool Tip: To apply 3/8” wide clamps, use S03289 If clamp tension needs to be released before locking, move adapter kit. -

Extended Performance Techniques and Compositional Style in the Solo

EXTENDED PERFORMANCE TECHNIQUES AND COMPOSITIONAL STYLE IN THE SOLO CONCERT VIBRAPHONE MUSIC OF CHRISTOPHER DEANE Joshua D. Smith, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2008 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Christopher Deane, Committee Member Terri Sundberg, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Smith, Joshua D., Extended performance techniques and compositional style in the solo concert vibraphone music of Christopher Deane. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2008, 66 pp., 1 table, 8 figures, 20 musical examples, references, 29 titles. Vibraphone performance continues to be an expanding field of music. Earliest accounts of the presence of the vibraphone and vibraphone players can be found in American Vaudeville from the early 1900s; then found shortly thereafter in jazz bands as early as the 1930s, and on the classical concert stage beginning in 1949. Three Pieces for Vibraphone, Opus 27, composed by James Beale in 1959, is the first solo concert piece written exclusively for the instrument. Since 1959, there have been over 690 pieces written for solo concert vibraphone, which stands as evidence of the popularity of both the instrument and the genre of solo concert literature. Christopher Deane has contributed to solo vibraphone repertoire with works that are regarded as staples in the genre. Deane’s compositions for vibraphone consistently expand the technical and musical potential of the instrument. -

Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE June 1992 Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Although the words “he,” “him,” and “his” are used sparingly in this course to enhance communication, they are not intended to be gender driven or to affront or discriminate against anyone. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. NAVAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROGRAM MANAGEMENT SUPPORT ACTIVITY PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32559-5000 ERRATA NO. 1 May 1993 Specific Instructions and Errata for Nonresident Training Course TOOLS AND THEIR USES 1. TO OBTAIN CREDIT FOR DELETED QUESTIONS, SHOW THIS ERRATA TO YOUR LOCAL-COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER). THE LOCAL COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER) IS DIRECTED TO CORRECT THE ANSWER KEY FOR THIS COURSE BY INDICATING THE QUESTIONS DELETED. 2. No attempt has been made to issue corrections for errors in typing, punctuation, etc., which will not affect your ability to answer the question. 3. Assignment Booklet Delete the following questions and write "Deleted" across all four of the boxes for that question: Question Question 2-7 5-43 2-54 5-46 PREFACE By enrolling in this self-study course, you have demonstrated a desire to improve yourself and the Navy. Remember, however, this self-study course is only one part of the total Navy training program. Practical experience, schools, selected reading, and your desire to succeed are also necessary to successfully round out a fully meaningful training program. THE COURSE: This self-study course is organized into subject matter areas, each containing learning objectives to help you determine what you should learn along with text and illustrations to help you understand the information. -

PLYWOOD MALLET.Pdf

PLYWOOD MALLET Slick method of making a mallet - never need to worry about the handle loosening. See my earlier post re ergonomic parameters, apparently you should determine the bevel angle on the striking face based on mallet handle length and the length of your arm from elbow to wrist. Who knew. With three layers of 3/4" plywood, it's 2-1/4" wide, maybe just add a 1/2" layer on each side if you need something a little beefier - or maybe build in a cavity and fill it with lead shot?. The handle winds up only 3/4" thick, thinking that maybe an additional 1/4" layer on either side would let you get a little more rounded profile to the grip area - easy enough to do though (maybe make patterns to use on the router table) and Baltic Birch plywood would be the way to go. Mallet Head Angle By swirt on March 30, 2011 at 6:30 am in techniques, tools I’ve seen this issue come up and get discussed on several forums. A joiners mallet is pretty simple to make, so it is a quick and satisfying shop project to get one constructed, but then the question arises, “what angle should be put on the head?” This is an important question with advice ranging from “we don’t need no stinking angle” to use the angle that allows it to sit flat on a bench. I discovered the answer to this question in a few old Timber Framing books. It makes sense that a Timber Framer would have the answer, as they do more chiseling than most woodworkers, and certainly heavier chiseling than all. -

CLASSIC WORKBENCH Design, Construction Notes & Techniques

BENCHCRAFTED CLASSIC WORKBENCH Design, Construction Notes & Techniques Copyright, Benchcrafted December 2016 www.benchcrafted.com 1 DESIGN When we set out to design a new workbench for our customers, from the very beginning we decided it should, above all, be simple. Not only in function, but also to build. We make no bones about it, our vises are designed and made to work sweetly, but not to a price point. However, not everyone is ready for their ultimate Split Top Roubo bench build, either monetarily, or technically. For those looking to get their feet wet in traditional woodworking, using time-proven techniques and tools, this bench will provide all the workholding required to test the waters. For many, this will be all the bench you need, and for others it will be an excellent springboard to our Split Top Roubo, while keeping the Classic as a second bench. The Classic Workbench is based largely on the famous Plate 11 workbench from Roubo’s “The Art of the Joiner”. We’ve built dozens of these “Roubo” benches over the past decade, helped others build hundreds more and examined extant French benches from the period. We’ve haven’t changed our opinion on this fundamental design. The Classic is a simpler, easier to build version of Roubo’s Plate 11 bench that captures all the functionality of Roubo’s design. French technical schools of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were outfitted with benches just like this. Paring down the bench to its essentials, we’ve incorporated our Classic Leg Vise, Planing Stop and Holdfast as workholding devices. -

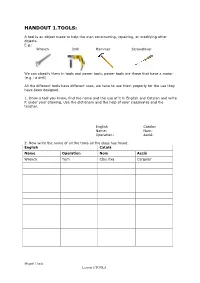

Handout 1.Tools

HANDOUT 1.TOOLS: A tool is an object made to help the man constructing, repairing, or modifying other objects. E.g.: Wrench Drill Hammer Screwdriver L We can classify them in tools and power tools, power tools are those that have a motor (e.g.: a drill) All the different tools have different uses, we have to use them properly for the use they have been designed. 1. Draw a tool you know, find the name and the use of it in English and Catalan and write it under your drawing. Use the dictionary and the help of your classmates and the teacher. English Catalan Name: Nom: Operation: Acció: 2. Now write the name of all the tools all the class has found: English Català Name Operation Nom Acció Wrench Turn Clau fixa Cargolar Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 2.TOOLS TABLE: Here’s a list of the most common tools in the workshop of the school: Rasp hacksaw Coping saw handsaw gimlet clamp C-clamp pliers Needle-nose pliers Round nose pliers Wire stripping pliers shears Hammer Ball-peen hammer Nilon mallet Riveting tool Rubber mallet Wrench (spanner) Flat head screwdriver Hot glue gun Torx screwdriver Flat Round file Bench vice file k Drill allen key Adjustable spanner Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 3. EMPTY TABLE: 3. Now hide the page you have been using before and in groups try to write all the names Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 4.OPERATIONS: 1. These are different operations we can do with the tools in the workshop.