Office of the Ohio Public Defender in Support of Appellants Sherry Bembry and Harsimran Singh ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

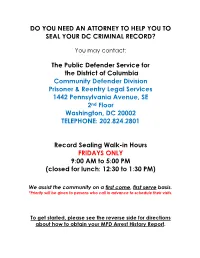

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin

Marquette Law Review Volume 91 Issue 1 Symposium: Dispute Resolution in Criminal Article 16 Law Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin, 91 Marq. L. Rev. 357 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol91/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL DISCUSSION PLEA BARGAINING FROM THE CRIMINAL LAWYER'S PERSPECTIVE: PLEA BARGAINING IN WISCONSIN* PANELISTS E. Michael McCann FormerDistrict Attorney, Milwaukee County; Boden Teaching Fellow & Adjunct Professor of Law, Marquette UniversityLaw School Michelle Jacobs FirstAssistant United States Attorney, Eastern Districtof Wisconsin Erik Peterson United States Attorney, Western Districtof Wisconsin Dean Strang Hurley, Burish & Stanton, S.C. Nathan Fishbach Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek S. C. Deja Vishny Office of the Wisconsin State Public Defender MODERATOR Daniel D. Blinka Professorof Law, Marquette University Law School This panel discussion was held as part of the Conference on Plea Bargaining on April 14, 2007, at Marquette University Law School. The transcript of the Panel Discussion has been lightly edited. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW [91:357 The primary purpose of the Conference is to present diverse views on plea bargaining. In addition to the articles, which represent varying academic and policy perspectives, we have assembled a panel of criminal law practitioners to contribute their insights and experience. -

Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 5 Article 4 1915 Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayer C. Goldman, Necessity for a Public Defender, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 660 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE NECESSITY FOR A PUBLIC DEFENDER MAYE C. GOLDMAN' Among the grave legal and sociological reforms which are being seriously urged at present by thinking people, there is being actively agitated the important proposition of creating the office of a Public Defender to defend indigent persons accused of crime. If by the establishment of such an office, the standard of our criminal jurisprudence can be raised and the principles of human justice thereby placed upon a more solid foundation, the inevitable result thereof must be, that the suspicion now lurking in the public mind to the effect that a discrimination exists between the rich and the poor, must give way to a wholesome realization of the fact that our much vaunted theory of "equality before the law" has become an actuality-instead of a mere high-sounding phrase. It must be apparent to all, that the important consideration in the trial of any cause, is, (or ought to be) to ascertain the truth- and not a mere contest in which one side or the other is permitted to gain an advantage by superior strategy, skill or power. -

Bail Reviewed: Report of the Court Observation Project

Bail Reviewed: Report of the Court Observation Project Maryland Office of the Public Defender Justice, Fairness and Dignity for All March 2018 About The Maryland Office of the Public Defender (OPD) is an independent state agency created in 1971 by the Maryland General Assembly. With over 900 employees, including 570 attorneys, OPD is the largest legal services organization in Maryland. Its mission is to provide superior legal representation to indigent defendants in the State of Maryland. Acknowledgments The Community Court Watch was supported by the Open Society Institute – Baltimore (OSI-Baltimore). OSI–Baltimore is the only U.S. field office of Open Society Foundations. They focus on the root causes of three intertwined problems in Baltimore and in Maryland: drug addiction, an over-reliance on incarceration, and obstacles that impede youth succeeding inside and out of the classroom. They also foster and support a network of 190 Community Fellows, a corps of dynamic activists and social entrepreneurs implementing projects that address problems in underserved communities in Baltimore City. The authors would also like to thank the organizations that helped recruit community volunteers: Baltimore Hebrew Congregation, Homewood Friends, Justice and Recovery Advocates, Justice Policy Institute, Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, Out for Justice, NAMI- Howard County, and University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please visit: http://www.opd.state.md.us Follow us on Twitter: @MarylandOPD For press inquiries, please contact: Melissa Rothstein [email protected] Executive Summary Whether someone accused of a crime is detained pending trial is among the most critical factors in the outcome of the case and the person’s well-being. -

Antonio Chaparro Nieves V. Office of the Public Defender (A-69-18) (082262)

SYLLABUS This syllabus is not part of the Court’s opinion. It has been prepared by the Office of the Clerk for the convenience of the reader. It has been neither reviewed nor approved by the Court. In the interest of brevity, portions of an opinion may not have been summarized. Antonio Chaparro Nieves v. Office of the Public Defender (A-69-18) (082262) Argued January 6, 2020 -- Decided April 15, 2020 LaVECCHIA, J., writing for the Court. The Court considers whether the Tort Claims Act (TCA), which governs tort actions filed against public entities and employees, applies to a criminal defendant’s legal malpractice claim filed against his public defender. The Court also considers whether, if the TCA applies, a claim for loss of liberty damages is subject to its “verbal threshold” for pain and suffering awards, as set forth in N.J.S.A. 59:9-2(d). This case arises out of the representation of plaintiff Antonio Chaparro Nieves by a state public defender, Peter Adolf, Esq. After his conviction, Nieves was granted post- conviction relief based on the ineffective assistance of counsel at trial. DNA evidence later confirmed that Nieves was not the perpetrator, and the underlying indictment against him was dismissed. Nieves subsequently recovered damages from the State for the time he spent wrongfully imprisoned. He then filed the present legal malpractice action seeking damages against the Office of the Public Defender (OPD) and Adolf. Defendants moved for summary judgment, arguing that the TCA barred the damages sought because Nieves failed to vault N.J.S.A. -

Rule 3.111. Providing Counsel to Indigents

RULE 3.111. PROVIDING COUNSEL TO INDIGENTS (a) When Counsel Provided. A person entitled to appointment of counsel as provided herein shall have counsel appointed when the person is formally charged with an offense, or as soon as feasible after custodial restraint, or at the first appearance before a committing magistrate, whichever occurs earliest. (b) Cases Applicable. (1) Counsel shall be provided to indigent persons in all prosecutions for offenses punishable by imprisonment (or by incarceration in a juvenile corrections institution) including appeals from the conviction thereof. Counsel does not have to be provided to an indigent person in a prosecution for a misdemeanor or violation of a municipal ordinance if the judge, before trial, files in the cause a statement in writing an order of no imprisonment, certifying that the defendant will not be imprisoned if convicted. (A) If the court issues an order of no imprisonment after the public defender has been appointed to represent the defendant, the court shall discharge the public defender. (B) If the court determined that the defendant would be substantially disadvantaged by the discharge of the public defender, the court shall either: i. not discharge the public defender; or ii. discharge the public defender and allow the defendant a reasonable time to obtain private counsel, or if the defendant elects self-representation, a reasonable time to prepare for trial. (C) If the court withdraws its order of no imprisonment, it immediately shall appoint the public defender if the defendant is otherwise eligible for the services of the public defender. (D) This rule is to be used in conjunction with 3.994. -

Speechless: the Silencing of Criminal Defendants

SPEECHLESS: THE SILENCING OF CRIMINAL DEFENDANTS ALEXANDRA NATAPOFF* Over one million defendants pass through the criminal justice system every year, yet we almost never hear from them. From the first Miranda warnings, through trial or guilty plea, and finally at sentencing, most defendants remain silent. They are spoken for by their lawyers or not at all. The criminal system treats this perva- sive silencing as protective, a victory for defendants. This Article argues that this silencing is also a massive democratic and human failure. Our democracy prizes individual speech as the main antidote to governmental tyranny, yet it silences the millions of poor, socially disadvantaged individuals who directly face the coercive power of the state. Speech also has important cognitive and dignitary functions: It is through speech that defendants engage with the law, understand it, and express anger, remorse, and their acceptance or rejection of the criminal justice process. Since defendants speak so rarely, however, these speech functions too often go unfulfilled. Finally, silencing excludes defendants from the social narratives that shape the criminal justice system itself, in which society ultimately decides which collective decisions are fair and who should be punished. This Article describes the silencing phenomenon in practice and in doctrine, and identifies the many unrecog- nized harms that silence causes to individual defendants, to the effectiveness of the criminal justice system, and to the democratic values that underlie the process. It concludes that defendant silencing should be understood and addressed in the con- text of broader inquiries into the (non)adversarialand (un)democraticfeatures of our criminal justice system. -

San Francisco Public Defender's Office

SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC DEFENDER JEFF ADACHI – PUBLIC DEFENDER MATT GONZALEZ – CHIEF ATTORNEY RACIAL JUSTICE COMMITTEE PLAN FOR POLICE REFORM 1. Officers must have a minimum 24 hours of training on implicit bias and its effects, including perspectives of people of color unlawfully detained while walking or driving. Classes must include the impact of implicit bias on officer decision-making in the field. Additionally, officers must participate in periodic cultural competency training and education throughout their career. 2. All Field Training Officers’ performance must be reviewed annually for any documented history of racial bias, excessive force, unlawful search and seizure and false reports, to determine if they are fit to train other officers. 3. The Police Department must make every effort to assign positions in black and brown communities to those officers who live in the communities they are patrolling. The City should provide financial incentives to officers who choose to live in the communities they are policing. 4. All officers, including plainclothes, shall be equipped with body cameras, which must be on and operating while the officer is on duty. A willful failure to turn on the equipment shall subject the officer to disciplinary action. Police officer contact with civilians which is not recorded may be deemed unreasonable by the courts and/or the Office of Citizen Complaints. 5. Whenever a shooting of a civilian by a police officer occurs, an independent investigation shall be conducted by an agency outside the SF Police Department and the SF District Attorney’s Office. Prosecutions of officer- involved shootings shall proceed by way of complaint rather than by grand jury indictment.