Speechless: the Silencing of Criminal Defendants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

Judge Donohue's Courtroom Procedures

JUDGE DONOHUE’S COURTROOM PROCEDURES I. INTRODUCTION A. Phone / Fax The office phone number is (541) 243-7805. During trials, your office, witnesses and family may leave messages with the judge’s judicial assistant. Those messages will be given to you by the courtroom clerk. Please call before sending faxes. The fax number is (541) 243-7877. You must first contact the judge’s judicial assistant before sending a fax transmission. There is a 10 page limit to the length of documents that can be sent by fax. We do not provide a fax service. We will not send an outgoing fax for you. B. Delivery of Documents You must file original documents via File and Serve. Please do not deliver originals to the judge or his judicial assistant unless otherwise specified in UTCR or SLR. You may hand- deliver to room 104, or email copies of documents to [email protected]. II. COURTROOM A. General Judge Donohue’s assigned courtroom is Courtroom #2 located on the second floor of the courthouse. B. Cell Phones / PDA’s Cell phones, personal digital assistant devices (PDA’s) and other types of personal electronic equipment may not be used in the courtroom without permission from the judge. If you bring them into the courtroom, you must turn them off or silence the ringer. C. Food, Drinks, Chewing Gum, Hats No food, drinks or chewing gum are permitted in the courtroom. Hats may not be worn in the courtroom. Ask the courtroom clerk if you need to seek an exception. JUDGE DONOHUE’S COURTROOM PROCEDURES (August 2019) Page 1 of 9 D. -

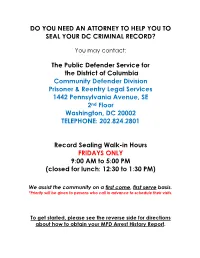

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

1 Hon. Joel M. Cohen Part 3 – Practices and Procedures

HON. JOEL M. COHEN PART 3 – PRACTICES AND PROCEDURES (revised September 14, 2020) Supreme Court of the State of New York Commercial Division 60 Centre Street, Courtroom 208 New York, NY 10007 Part Clerk/Courtroom Phone: 646-386-3275 Chambers Phone: 646-386-4927 Principal Court Attorney: Kartik Naram, Esq. ([email protected]) Law Clerk: Herbert Z. Rosen, Esq. ([email protected]) Courtroom Part Clerk: Sharon Hill ([email protected]) Chambers Email Address: [email protected] Courtroom hours are from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Lunch recess is from 1 p.m. to 2:15 p.m. The courtroom is closed during that time. Preliminary, Compliance, and Status Conferences generally are held on Tuesdays beginning at 9:30 a.m. Pre-trial Conferences and oral argument on motions will be held as scheduled by the Court. I. GENERAL A. The Rules of the Commercial Division, 22 NYCRR 202.70, are incorporated herein by reference, subject to minor modifications described below. B. The Court strongly encourages substantive participation in court proceedings by women and diverse lawyers, who historically have been underrepresented in the commercial bar. The Court urges litigants to be mindful of in-court advocacy opportunities for such lawyers who have not previously had substantial court experience in commercial cases, as well as less experienced lawyers generally (i.e. lawyers practicing for five years or less). A representation that oral argument on a motion will be handled or shared by such a lawyer will weigh in favor of holding a hearing when otherwise the motion would be decided on the papers. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

Great Minds Speak Alike: Inter-Court Communication of Metaphor in Education Finance Litigation

Great Minds Speak Alike: Inter-Court Communication of Metaphor in Education Finance Litigation Matt Saleh Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Matt Saleh All rights reserved ABSTRACT Great Minds Speak Alike: Inter-Court Communication of Metaphor in Education Finance Litigation Matt Saleh This project uses a mixed methods approach to analyze the communication of metaphors about educational equity and adequacy, between co-equal state supreme courts in education finance litigation (1971-present). Evidence demonstrates that a number of pervasive metaphors about students and educational opportunities (“sound basic education,” “marketplace of ideas,” students as “competitors in the global economy”) have been shared and conventionalized within judicial networks, with significant implications for how courts interpret educational rights under state constitutions. The project first conducts a qualitative discourse analysis of education finance litigation in New York State (four cases) using Pragglejaz Group’s (2007) Metaphor Identification Procedure, to identify micro-level examples of metaphor usage in actual judicial discourse. Then, it performs quantitative and qualitative social network analysis of the entire education finance judicial network for state supreme courts (65 cases), to analyze two different “relations” between this set of actors: shared citation (formal relation) and shared metaphor (informal relation). Data analysis shows that there exist both formal and informal channels of judicial communication—communication we can “see,” and communication we can’t—and commonalities in discursive strategies (informal ties) are, in some ways, potentially more cohesive than direct, formal ties. -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

CLE Cover Sheet

Special Committee on Criminal Justice Roundtable “Pandemic in the Criminal Justice System: Are We Better or Worse Off?” CLE Course Number 5226 Level: Intermediate Approval Period: 6/3/21 – 12/31/22 CLE Credits Certification Credits General 5.0 Appellate Practice 5.0 Ethics 1.0 Criminal Appellate Practice 5.0 Technology 1.0 Criminal Trial Practice 5.0 Juvenile Law 5.0 The Florida Bar’s Special Committee on Criminal Justice is comprised of a diverse group of lawyers, judges, and non-lawyer members representing a number of criminal law-related associations as well as the Legislature. The COVID-19 pandemic has manifestly changed how the justice system has operated, especially in the criminal justice realm. We are currently examining what changes will become permanent, and what processes have negatively affected the rights of criminal defendants. The panels include many of the leading Florida criminal justice practitioners, and will discuss a variety of issues including court administration, funding issues, technology challenges, and constitutional issues. Biography of Moderators/Panelists 12:00 – 12:15 Greeting *Co-Chair Michelle Suskauer, Dimond Kaplan & Rothstein, P.A., West Palm Beach Michelle Suskauer a criminal defense attorney and the managing partner of the West Palm Beach office of Dimond Kaplan & Rothstein, P.A., a law firm that focuses on criminal defense and finance fraud with offices in West Palm Beach, Miami, Naples, Los Angeles and New York. Michelle began her legal career as an assistant public defender in West Palm Beach. She has been practicing in Palm Beach County since 1991 with a focus in criminal law in both state and federal courts. -

Charles M. Sevilla 1010 Second Avenue, Suite 1825 San Diego, California 92101-4902 619-232-2222-Tel

Charles M. Sevilla 1010 Second Avenue, Suite 1825 San Diego, California 92101-4902 619-232-2222-tel www.charlessevilla.com EDUCATION LL.M., George Washington University, Washington D.C., 1971 J.D., University of Santa Clara, Santa Clara, California, 1969 B.A., San Jose State University, San Jose, California, 1966 ADMITTED TO PRACTICE: California: Supreme Court of California; U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California; U.S. District Court for Southern District of California; U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Washington, D.C.: U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia; U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia; Supreme Court of the United States EMPLOYMENT: Law Office of Charles Sevilla, 2004 - present Partner, Cleary & Sevilla, LLP, 1983 - 2004 Chief Deputy State Public Defender, 1979 to 1983 Chief Assistant State Public Defender, Los Angeles, 1976 to 1979 Federal Defenders, San Diego, California; trial attorney, 1971 to 1972; Chief Trial Attorney, 1972 to 1976 Washington, D.C., private practice, 1971 VISTA Legal Services, Urban Law Institute, Washington, D.C., Staff Attorney, 1969 to 1971 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS: “Antisocial Personality Disorder: Justification for the Death Penalty?” 10 Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 247, University of San Diego School of Law (1999). "Criminal Defense Lawyers and the Search for Truth," 20 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 519 (Winter 1997). "April 20, 1992: A Day in the Life," 30 Loyola Law Review 95 (November 1996) “Redefining Federal Habeas Corpus and Constitutional Rights: Procedural Preclusion,” 52 National Lawyer’s Guild Practitioner 33 (1995). "Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents: The Death Penalty Case of Robert Alton Harris," 40 U.C.L.A. -

“You Have the Right to an Attorney,” but Not Right Now: Combating Miranda's Failure by Advancing the Point of Attachment

DEARBORN_LEAD_MACRO 6/6/2011 9:18 PM “You Have the Right to an Attorney,” but Not Right Now: Combating Miranda’s Failure by Advancing the Point of Attachment Under Article XII of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights D. Christopher Dearborn1 I. INTRODUCTION Over forty years’ worth of popular culture has led most Americans to believe that they have a “right to an attorney” upon arrest.2 We have watched this familiar scene unfold in countless movies and television shows: the police close in on the lone (and undoubtedly guilty) suspect, pin him against a wall, slap on the cuffs, and triumphantly recite his “Miranda warnings,” which apparently include the right to counsel. Technically, officers here are referring to a suspect’s limited Fifth Amendment right, upon “clearly” and “unambiguously” invoking it,3 to the presence of an attorney before custodial interrogation by the police.4 This idea would probably strike most people as extremely sensible—that, upon arrest, you should have the opportunity to speak with a lawyer even if you cannot afford to hire one. However, the “right” guarantees neither access to a lawyer to explain the procedural complexities of a criminal case, nor unbiased, professional advice on whether it is prudent to waive any constitutional protections.5 Rather, Miranda only guarantees the right, once affirmatively invoked, to not be asked questions by the police outside the presence of an attorney.6 As a practical reality in Massachusetts, 1. Associate Clinical Professor of Law, Suffolk University Law School. I want to thank my colleagues Frank Rudy Cooper and Ragini Shah for their valuable insights. -

The Ethical Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness

Marquette Law Review Volume 99 Article 4 Issue 2 Winter 2015 The thicE al Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness: How Modern Ethics Rules Fail to Prevent Truthful Witnesses from Being Discredited Through Unethical Means Todd A. Berger Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Courts Commons, and the Evidence Commons Repository Citation Todd A. Berger, The Ethical Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness: How Modern Ethics Rules Fail to Prevent Truthful Witnesses from Being Discredited Through Unethical Means, 99 Marq. L. Rev. 283 (2015). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol99/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETHICAL LIMITS OF DISCREDITING THE TRUTHFUL WITNESS: HOW MODERN ETHICS RULES FAIL TO PREVENT TRUTHFUL WITNESSES FROM BEING DISCREDITED THROUGH UNETHICAL MEANS TODD A. BERGER* Whether the criminal defense attorney may ethically discredit the truthful witness on cross-examination and later during closing argument has long been an area of controversy in legal ethics. The vast majority of scholarly discussion on this important ethical dilemma has examined it in the abstract, focusing on the defense attorney’s dual roles in a criminal justice system that is dedicated to searching for the truth while simultaneously requiring zealous advocacy even for the guiltiest of defendants. Unlike these previous works, this particular Article explores this dilemma from the perspective of the techniques that criminal defense attorney’s use on cross-examination and closing argument to cast doubt on the testimony of a credible witness.