Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

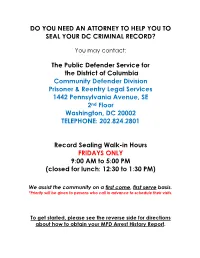

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. V. North Carolina

THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ADOPTS A REASONABLE JUVENILE STANDARD IN J.D.B. V NORTH CAROLINA FOR PURPOSES OF THE MIRANDA CUSTODY ANALYSIS: CAN A MORE REASONED JUSTICE SYSTEM FOR JUVENILES BE FAR BEHIND? Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney∗ I. Introduction II. The Reasonable Person Standard a. Background b. The Reasonable Person Standard and Children: Kids Are Different III. Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida: Embedding Developmental Research Into the Court’s Constitutional Analysis IV. From Miranda v. Arizona to J.D.B. v. North Carolina V. J.D.B. v. North Carolina: The Facts and The Analysis VI. Reasonableness Applied: Justifications, Defenses, and Excuses a. Duress Defenses b. Justified Use of Force c. Provocation d. Negligent Homicide e. Felony Murder VII. Conclusion I. Introduction The “reasonable person” in American law is as familiar to us as an old shoe. We slip it on without thinking; we know its shape, style, color, and size without looking. Beginning with our first-year law school classes in torts and criminal law, we understand that the reasonable person provides a measure of liability and responsibility in our legal system.1 She informs our * ∗Marsha L. Levick is the Deputy Director and Chief Counsel for Juvenile Law Center, a national public interest law firm for children, based in Philadelphia, Pa., which Ms. Levick co-founded in 1975. Ms. Levick is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University School of Law. Elizabeth-Ann “LT” Tierney is the 2011 Sol and Helen Zubrow Fellow in Children's Law at the Juvenile Law Center. -

The Climate Necessity Defense: Proof and Judicial Error in Climate Protest Cases

The Climate Necessity Defense: Proof and Judicial Error in Climate Protest Cases Lance N. Long Ted Hamilton* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 58 II. ATTEMPTS TO ASSERT THE CLIMATE NECESSITY DEFENSE ............. 61 III. THE COMMON AND STATUTORY LAW OF NECESSITY ...................... 69 A. Development of the Necessity Defense .................................. 69 B. Recent Uses of the Necessity Defense .................................... 74 IV. THE CASE FOR CLIMATE NECESSITY—AND WHERE THE COURTS ARE GETTING IT WRONG ........................................................................ 78 A. Choice of Evils ...................................................................... 81 B. Causation .............................................................................. 84 C. Imminence ............................................................................ 89 D. Reasonable Legal Alternatives ............................................... 96 E. Direct vs. Indirect Civil Disobedience .................................. 104 F. The Right to a Jury .............................................................. 108 1. The Right to Have Facts Heard by a Jury ....................... 108 2. The Right to Present a Complete Defense ...................... 110 V. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 115 * Lance N. Long is a Professor of Law at Stetson University College of Law. Ted Hamilton is a co-founder and staff attorney -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

Right to Self-Defence in National and International Law: the Role of the Imminence Requirement

"I KNOW NOT WITH WHAT WEAPONS WORLD WAR Im WILL BE FOUGHT, BUT WORLD WAR IV WILL BE FOUGHT WITH SUCKS AND STONES." EINSTEIN1 THE RIGHT TO SELF-DEFENCE IN NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LAW: THE ROLE OF THE IMMINENCE REQUIREMENT Onder Bakircioglu* This article explores the doctrine of self-defence within the context of the challenges directed at the imminence requirement, from the perspective of both national and international law. The article will attempt to illustrate that the requirement of imminence underlines the political character of the self-defence doctrine wherein private force may only be resorted to in the absence of institutional protection. This study will argue that the imminence rule can not merely be regarded as a "proxy" for establishing necessity; rather, the elements of imminence, necessity, and proportionality are inextricably connected to ensure that defensive force is only resorted to when national or international authorities are not in a position to prevent an illegal aggression, and that the defensive lethal force is not abused. INTRODUCTION The September 11 attacks aroused controversy as to whether anticipatory or pre-emptive self-defence 2 is allowed under customary international law, and if so, under what circumstances. Following the devastating attacks on New York and Washington, the 2002 National Security Strategy (NSS) made it clear that the United States would act unilaterally to protect its security against "emerging threats before they are fully formed."3 This approach signified a radical departure from the collective security system by the sole existing super power. Indeed, while the right to national self-defence has been recognized as an inherent right of states since the very emergence of international law, * Onder Bakircioglu, Lecturer in Law, Queen's University Belfast. -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

Legislating the Necessity Defense in Criminal Law

Denver Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 March 2021 Legislating the Necessity Defense in Criminal Law Lawrence P. Tiffany Carl A. Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Lawrence P. Tiffany & Carl A. Anderson, Legislating the Necessity Defense in Criminal Law, 52 Denv. L.J. 839 (1975). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. LEGISLATING THE NECESSITY DEFENSE IN CRIMINAL LAW By LAWRENCE P. TIFFANY,* CARL A. ANDERSON** INTRODUCTION The necessity, or choice of evils, defense has not been raised very frequently. This is, no doubt, partly due to the relative rarity of such situations and to the fact that police and prosecutors screen out most of those cases that do come to their attention. The importance of this body of law, however, may increase as recodification of criminal law spreads. About 24 new criminal codes have been adopted in the past dozen years, and almost as many are in the legislative process. Many of these new codes have a section dealing with the necessity defense. This analysis is based largely on these new statutes and proposals, whether or not they have been enacted, as they are likely to be interpreted in light of the existing, but rather meager, case law of this defense.' *Professor of Law, University of Denver College of Law; A.B., 1961, LL.B., 1963, Washington University; S.J.D., 1967, University of Wisconsin. -

Self-Defense Without Imminence

ARTICLES SELF-DEFENSE WITHOUT IMMINENCE Fritz Allhoff* ABSTRACT The doctrine of self-defense allows that otherwise criminal force can be justi®ed so long as the actor reasonably believes its use necessary to protect against imminent and unlawful attack. Supposing that the force is necessary to dispel the attack, why the further requirement that the attack is imminent? The restriction precludes the use of force which, ex hypothesi, is the only way that the actor could defend himself. This Article surveys and critiques the rationale for the imminence requirement, arguing that it should be jettisoned in favor of a more expansive conception of self-defense. While the focus is on domestic law, the paper concludes by gesturing towards implications for international law as well, particularly with regards to preventive war (i.e., war against non-imminent threats). I. IMMINENCE AND NECESSITY Self-defense has long been taken to justify an otherwise illicit use of force. William Blackstone, characterizing the eighteenth-century common law of England, provided: [I]f the party himself, or any of these his relations, be forcibly attacked in his person or property, it is lawful for him to repel force by force; and the breach of the peace, which happens, is chargeable upon him only who began the affray. For the law, in this case, respects the passions of the human mind; and ... makes it lawful in him to do himself that immediate justice, to which he is prompted by nature, and which no prudential motives are strong enough to restrain. It considers that the future process of law is by no means an adequate remedy for injuries accompanied with force; since it is impossible to say, to * Fritz Allhoff, J.D., Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Western Michigan University. -

Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin

Marquette Law Review Volume 91 Issue 1 Symposium: Dispute Resolution in Criminal Article 16 Law Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin, 91 Marq. L. Rev. 357 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol91/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL DISCUSSION PLEA BARGAINING FROM THE CRIMINAL LAWYER'S PERSPECTIVE: PLEA BARGAINING IN WISCONSIN* PANELISTS E. Michael McCann FormerDistrict Attorney, Milwaukee County; Boden Teaching Fellow & Adjunct Professor of Law, Marquette UniversityLaw School Michelle Jacobs FirstAssistant United States Attorney, Eastern Districtof Wisconsin Erik Peterson United States Attorney, Western Districtof Wisconsin Dean Strang Hurley, Burish & Stanton, S.C. Nathan Fishbach Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek S. C. Deja Vishny Office of the Wisconsin State Public Defender MODERATOR Daniel D. Blinka Professorof Law, Marquette University Law School This panel discussion was held as part of the Conference on Plea Bargaining on April 14, 2007, at Marquette University Law School. The transcript of the Panel Discussion has been lightly edited. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW [91:357 The primary purpose of the Conference is to present diverse views on plea bargaining. In addition to the articles, which represent varying academic and policy perspectives, we have assembled a panel of criminal law practitioners to contribute their insights and experience. -

The Difference in Criminal Defense and the Difference It Makes

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2003 The Difference in Criminal Defense and the Difference It Makes Abbe Smith Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/215 11 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol'y 83-140 (2003) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications February 2010 The Difference in Criminal Defense and the Difference It Makes 11 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol’y 83-140 (2003) Abbe Smith Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/215/ Posted with permission of the author The Difference in Criminal Defense and the Difference It Makes Abbe Smith* In 1894 I opened an office and went into private practice .... When I began, it was with the intention of trying only civil cases .... I had never had anything to do with criminal cases, and, like most other lawyers, did not want to take them .... -Clarence Darrowl Strange as it may seem I grew to like to defend men and women charged with crime. It soon came to be something more than winning or losing a case. [It] meant more than the quibbling with lawyers and juries, to get or keep money for a client so that I could take part of what I won or saved for him: I was dealing with life, with its hopes and fears, its aspirations and despairs. -

Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 5 Article 4 1915 Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayer C. Goldman, Necessity for a Public Defender, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 660 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE NECESSITY FOR A PUBLIC DEFENDER MAYE C. GOLDMAN' Among the grave legal and sociological reforms which are being seriously urged at present by thinking people, there is being actively agitated the important proposition of creating the office of a Public Defender to defend indigent persons accused of crime. If by the establishment of such an office, the standard of our criminal jurisprudence can be raised and the principles of human justice thereby placed upon a more solid foundation, the inevitable result thereof must be, that the suspicion now lurking in the public mind to the effect that a discrimination exists between the rich and the poor, must give way to a wholesome realization of the fact that our much vaunted theory of "equality before the law" has become an actuality-instead of a mere high-sounding phrase. It must be apparent to all, that the important consideration in the trial of any cause, is, (or ought to be) to ascertain the truth- and not a mere contest in which one side or the other is permitted to gain an advantage by superior strategy, skill or power.