Liman Workshop Rationing Access Week 6 Abolishing Money Bail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

Restoring the Confrontation Clause to the Sixth Amendment Randolph N

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1988 Restoring the Confrontation Clause to the Sixth Amendment Randolph N. Jonakait New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation UCLA Law Review, Vol. 35, Issue 4 (April 1988), pp. 557-622 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. ARTICLES RESTORING THE CONFRONTATION CLAUSE TO THE SIXTH AMENDMENT Randolph N. Jonakait* INTRODUCTION The relationship between the sixth amendment's con- frontation clause' and out-of-court statements by absent de- clarants is a difficult one.2 Before 1980, the Supreme Court * Professor of Law and Associate Dean, New York Law School. A.B., Princeton University, 1967;J.D., University of Chicago Law School, 1970; LL.M., New York University Law School, 1971. The author wishes to thank his colleague Professor Donald Hazen Zeigler for his helpful comments. 1. The sixth amendment states: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the wit- nesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining wit- nesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense. -

The Right to Counsel in Collateral, Post-Conviction Proceedings, 58 Md

Maryland Law Review Volume 58 | Issue 4 Article 4 The Right to Counsel in Collateral, Post- Conviction Proceedings Daniel Givelber Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Givelber, The Right to Counsel in Collateral, Post-Conviction Proceedings, 58 Md. L. Rev. 1393 (1999) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol58/iss4/4 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIGHT TO COUNSEL IN COLLATERAL, POST- CONVICTION PROCEEDINGS DANIEL GIVELBER* I. INTRODUCTION Hornbook constitutional law tells us that the state has no obliga- tion to provide counsel to a defendant beyond his first appeal as of right.1 The Supreme Court has rejected arguments that either the Due Process Clause or the Equal Protection Clause require that the right to counsel apply to collateral, post-conviction proceedings.2 The Court also has rejected the argument that the Eighth Amendment re- quires that the right to an attorney attach to post-conviction proceed- ings specifically in capital cases.' Without resolving the issue, the Court has acknowledged the possibility that there may be a limited right to counsel if a particular constitutional claim can be raised only in post-conviction proceedings.4 Despite their apparently definitive quality, none of the three cases addressing these issues involved a de- fendant who actually had gone through a post-conviction collateral proceeding unrepresented.5 * Interim Dean and Professor of Law, Northeastern University School of Law. -

Disentangling the Sixth Amendment

ARTICLES * DISENTANGLING THE SIXTH AMENDMENT Sanjay Chhablani** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................488 I. THE PATH TRAVELLED: A HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE COURT’S SIXTH AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE......................492 II. AT A CROSSROADS: THE RECENT DISENTANGLEMENT OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT .......................................................505 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................505 B. Right of Confrontation ...................................................512 III. THE ROAD AHEAD: ENTANGLEMENTS YET TO BE UNDONE.................................................................................516 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................516 B. The Right to Compulsory Process ..................................523 C. The Right to a Public Trial .............................................528 D. The Right to a Speedy Trial............................................533 E. The Right to Confrontation............................................538 F. The Right to Assistance of Counsel ................................541 CONCLUSION.................................................................................548 APPENDIX A: FEDERAL CRIMES AT THE TIME THE SIXTH AMENDMENT WAS RATIFIED...................................................549 * © 2008 Sanjay Chhablani. All rights reserved. ** Assistant Professor, Syracuse University College of Law. I owe a debt of gratitude to Akhil Amar, David Driesen, Keith Bybee, and Gregory -

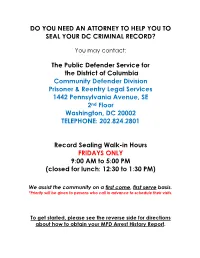

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

Sixth Amendment and the Right to Counsel

THE SIXTH AMENDMENT AND THE RIGHT TO COUNSEL RHEA KEMBLE BRECHERt The sixth amendment is vitally important and necessary, but I be- lieve that it contains a limited privilege. Attempts to extend the sixth amendment from beyond this limited sphere have generated difficulties and controversies. The sixth amendment reads: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.1 The first phrase, "[i]n all criminal prosecutions," indicates that sixth amendment rights commence only at the initiation of an adversary pro- ceeding, be it by indictment, arraignment, or criminal complaint. They are not implicated in the investigatory or the grand jury phase.' The sixth amendment guarantees that the defendant will have someone with her who understands the procedural rules, the rules of evidence, and who can give her other professional assistance. No language in the sixth amendment refers to the defendant's right to counsel of choice. Some courts of appeal, however, have found some kind of qualified right, or limited right, to counsel of choice.' The t Executive Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. This Article is adapted from a presentation given at the Symposium on Right to Counsel, March 1, 1988. -

The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence

Texas Law Review See Also Volume 94 Response The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence Brandon L. Garrett* I. Introduction Do we have a presumption of innocence in this country? Of course we do. After all, we instruct criminal juries on it, often during jury selection, and then at the outset of the case and during final instructions before deliberations. Take this example, delivered by a judge at a criminal trial in Illinois: "Under the law, the Defendant is presumed to be innocent of the charges against him. This presumption remains with the Defendant throughout the case and is not overcome until in your deliberations you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the Defendant is guilty."' Perhaps the presumption also reflects something more even, a larger commitment enshrined in a range of due process and other constitutional rulings designed to protect against wrongful convictions. The defense lawyer in the same trial quoted above said in his closings: [A]s [the defendant] sits here right now, he is presumed innocent of these charges. That is the corner stone of our system of justice. The best system in the world. That is a presumption that remains with him unless and until the State can prove him guilty beyond2 a reasonable doubt. That's the lynchpin in the system ofjustice. Our constitutional criminal procedure is animated by that commitment, * Justice Thurgood Marshall Distinguished Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law. 1. Transcript of Record at 13, People v. Gonzalez, No. 94 CF 1365 (Ill.Cir. Ct. June 12, 1995). 2. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

Advocating for Mandated Publicly Appointed Counsel at Bail Hearings

NOTES YOU MADE GIDEON A PROMISE, EH?: ADVOCATING FOR MANDATED PUBLICLY APPOINTED COUNSEL AT BAIL HEARINGS IN THE UNITED STATES THROUGH DOMESTIC COMPARISONS WITH CANADIAN PRACTICES AND LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS Lauren Elizabeth Lisauskas* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 159 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................. 162 A. The History of Bail .............................................................. 162 i. United States of America ................................................ 163 ii. Canada ........................................................................... 165 B. Criminal Justice Systems and Indigent Counsel ................. 166 i. United States of America ................................................ 166 ii. Canada ........................................................................... 167 III. ANALYSIS ......................................................................................... 169 A. American Practices .............................................................. 169 i. Sources of Law ................................................................ 169 ii. Open Questions of Law ................................................. 171 a. What is a “Critical Stage”? .................................... 171 b. Is There a Non-Constitutional Remedy? ................. 174 B. Canadian Practices ............................................................. 175 i. Sources of -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

Limitations on an Accused's Right to Counsel John W

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 38 | Issue 4 Article 7 1948 Limitations on an Accused's Right to Counsel John W. Kerrigan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation John W. Kerrigan, Limitations on an Accused's Right to Counsel, 38 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 375 (1947-1948) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 1947] CRIMINAL LAW COMMENTS or social or economic status4 6 a member of the excluded class may cog- ently attack his conviction by such a jury on the grounds that he was denied equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.47 Furthermore, when the administration of any jury selec- tion procedure has resulted in the exclusion of such a class for similar reasons it is open to attack as violative of the due process clause. Finally, where the state prescribes a dual jury system, clear and con- vincing evidence showing a greatly disparate ratio of conviction by the special as compared with the general jury for a substantial length of time prior to trial may be used to prove the procedure violative of the equal protection clause and unconstitutional. DAVID W. KETLEa* Limitations on an Accused's Right to Counsel In the recent case of Foster v.