CED-81-2 There Is No Shortage of Freight Cars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Headquarters Assigned Accident Investigation Report HQ-2006-88

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Headquarters Assigned Accident Investigation Report HQ-2006-88 Union Pacific Midas, CA November 9, 2006 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT FRA File # HQ-2006-88 FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION 1.Name of Railroad Operating Train #1 1a. Alphabetic Code 1b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. Union Pacific RR Co. [UP ] UP 1106RS011 2.Name of Railroad Operating Train #2 2a. Alphabetic Code 2b. Railroad Accident/Incident N/A N/A N/A 3.Name of Railroad Responsible for Track Maintenance: 3a. Alphabetic Code 3b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. Union Pacific RR Co. [UP ] UP 1106RS011 4. U.S. DOT_AAR Grade Crossing Identification Number 5. Date of Accident/Incident 6. Time of Accident/Incident Month Day Year 11 09 2006 11:02: AM PM 7. Type of Accident/Indicent 1. Derailment 4. Side collision 7. Hwy-rail crossing 10. Explosion-detonation 13. Other (single entry in code box) 2. Head on collision 5. Raking collision 8. RR grade crossing 11. Fire/violent rupture (describe in narrative) 3. Rear end collision 6. Broken Train collision 9. Obstruction 12. Other impacts 01 8. Cars Carrying 9. HAZMAT Cars 10. Cars Releasing 11. People 12. Division HAZMAT Damaged/Derailed HAZMAT Evacuated 0 0 0 0 Roseville 13. Nearest City/Town 14. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Bilevel Rail Car - Wikipedia

Bilevel rail car - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilevel_rail_car Bilevel rail car The bilevel car (American English) or double-decker train (British English and Canadian English) is a type of rail car that has two levels of passenger accommodation, as opposed to one, increasing passenger capacity (in example cases of up to 57% per car).[1] In some countries such vehicles are commonly referred to as dostos, derived from the German Doppelstockwagen. The use of double-decker carriages, where feasible, can resolve capacity problems on a railway, avoiding other options which have an associated infrastructure cost such as longer trains (which require longer station Double-deck rail car operated by Agence métropolitaine de transport platforms), more trains per hour (which the signalling or safety in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The requirements may not allow) or adding extra tracks besides the existing Lucien-L'Allier station is in the back line. ground. Bilevel trains are claimed to be more energy efficient,[2] and may have a lower operating cost per passenger.[3] A bilevel car may carry about twice as many as a normal car, without requiring double the weight to pull or material to build. However, a bilevel train may take longer to exchange passengers at each station, since more people will enter and exit from each car. The increased dwell time makes them most popular on long-distance routes which make fewer stops (and may be popular with passengers for offering a better view).[1] Bilevel cars may not be usable in countries or older railway systems with Bombardier double-deck rail cars in low loading gauges. -

BIGGS APPRAISAL Railroading 101

BIGGS APPRAISAL Railroading 101 American Society of Appraisers Conference June, 2018 It is likely that you will encounter rail equipment if you are appraising a large industrial facility • Your asset list may include locomotives, freight cars, rail car movers, track maintenance of way equipment as well as track. • The purpose of this presentation is to give you an understanding of what you have and where you might look for information to support a credible valuation. The Association of American Railroads (AAR)is the Railroads centralized governing body. • It develops: • The Interchange Rules • The Standards and Recommended Practices • General Railroad Operating Practices • Processes Car Hire • Processes Movement records and car tracing information • Processes Car Repair Billing • Maintains the Rail Equipment Registration File (Commonly called Umler) • Develops Rail Equipment Specifications Federal Governing Bodies that impact Railroads • Department of Transportation • Federal Railroad Administration • Environmental Protection Administration • Surface Transportation Board The Interchange Rules The term Interchange rules applies to the rules found in the Field and Office manuals published by the Association of American Railroads. These rules apply to the running gear, couplers, safety appliances, brakes, wheels. A railcar could having a gaping hole in the side and still meet the interchange rules. The term suitable for loading the intended commodity is an important qualifier. Rail Car Identification • As of May 1, 2018 the North American Rail Fleet was comprised of 1,644,507 units in over 700 car types. • There are seven major rail car classifications: Boxcars, Covered Hoppers, Flat Cars, Gondolas, Hoppers, Tank Cars and Other Cars. • The Gross rail Load Capacity (GRL) or freight railcars fall in to three general categories 220,000 pounds (70 ton) 263,000 pounds (100 ton) • 286,000 pounds (100 Plus tons) is the modern standard car capacity. -

How Understanding a Railway's Historic Evolution Can Guide Future

College of Engineering, School of Civil Engineering University of Birmingham Managing Technical and Operational Change: How understanding a railway’s historic evolution can guide future development: A London Underground case study. by Piers Connor Submitted as his PhD Thesis DATE: 15th February 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Managing Technical & Operational Development PhD Thesis Abstract The argument for this thesis is that patterns of past engineering and operational development can be used to support the creation of a good, robust strategy for future development and that, in order to achieve this, a corporate understanding of the history of the engineering, operational and organisational changes in the business is essential for any evolving railway undertaking. It has been the objective of the author of this study to determine whether it is essential that the history and development of a railway undertaking be known and understood by its management and staff in order for the railway to function in an efficient manner and for it to be able to develop robust and appropriate improvement strategies in a cost-effective manner. -

Amtrak Cascades Fleet Management Plan

Amtrak Cascades Fleet Management Plan November 2017 Funding support from Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information The material can be made available in an alternative format by emailing the Office of Equal Opportunity at [email protected] or by calling toll free, 855-362-4ADA (4232). Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may make a request by calling the Washington State Relay at 711. Title VI Notice to Public It is the Washington State Department of Transportation’s (WSDOT) policy to assure that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex, as provided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise discriminated against under any of its federally funded programs and activities. Any person who believes his/her Title VI protection has been violated, may file a complaint with WSDOT’s Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). For additional information regarding Title VI complaint procedures and/or information regarding our non-discrimination obligations, please contact OEO’s Title VI Coordinator at 360-705-7082. The Oregon Department of Transportation ensures compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; 49 CFR, Part 21; related statutes and regulations to the end that no person shall be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Transportation on the grounds of race, color, sex, disability or national origin. -

Development of Load Rating Procedures for Railroad Flatcars for Use As Highway Bridges Based on Experimental and Numerical Studies

DEVELOPMENT OF LOAD RATING PROCEDURES FOR RAILROAD FLATCARS FOR USE AS HIGHWAY BRIDGES BASED ON EXPERIMENTAL AND NUMERICAL STUDIES PHASE III FINAL REPORT- Prepared for The Indiana Local Technical Assistance Program (LTAP) Prepared by Kadir C. Sener, Teresa L. Washeleski Robert J. Connor October 12, 2015 Purdue University School of Civil Engineering West Lafayette, Indiana 2 3 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 6 2 Background ............................................................................................................................. 6 3 Objective ................................................................................................................................. 7 4 Summary of Experimental Tests on RRFC Bridge................................................................. 7 4.1 RRFC Bridge Details ....................................................................................................... 7 4.2 Instrumentation................................................................................................................. 8 4.3 Testing Method ................................................................................................................ 9 5 Finite Element Modeling of RRFC ....................................................................................... 11 5.1 Model Part Details ......................................................................................................... -

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Headquarters Assigned Accident Investigation Report HQ-2007-55

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Headquarters Assigned Accident Investigation Report HQ-2007-55 Amtrak/Union Pacific (ATK/UP) Martinez, California October 1, 2007 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT FRA File # HQ-2007-55 FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION 1.Name of Railroad Operating Train #1 1a. Alphabetic Code 1b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. Amtrak [ATK ] ATK 105753 2.Name of Railroad Operating Train #2 2a. Alphabetic Code 2b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. Union Pacific RR Co. [UP ] UP 1007RS003 3.Name of Railroad Operating Train #3 3a. Alphabetic Code 3b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. N/A N/A N/A 4.Name of Railroad Responsible for Track Maintenance: 4a. Alphabetic Code 4b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. Union Pacific RR Co. [UP ] UP 1007RS003 5. U.S. DOT_AAR Grade Crossing Identification Number 6. Date of Accident/Incident 7. Time of Accident/Incident Month 10 Day 01 Year 2007 05:35: AM PM 8. Type of Accident/Indicent 1. Derailment 4. Side collision 7. Hwy-rail crossing 10. Explosion-detonation 13. Other Code (single entry in code box) 2. Head on collision 5. Raking collision 8. RR grade crossing 11. Fire/violent rupture (describe in narrative) 3. Rear end collision 6. Broken Train collision 9. Obstruction 12. Other impacts 09 9. -

Pullman Company Archives

PULLMAN COMPANY ARCHIVES THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY Guide to the Pullman Company Archives by Martha T. Briggs and Cynthia H. Peters Funded in Part by a Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chicago The Newberry Library 1995 ISBN 0-911028-55-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................. v - xii ... Access Statement ............................................ xiii Record Group Structure ..................................... xiv-xx Record Group No . 01 President .............................................. 1 - 42 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the President ...................... 2 - 34 Subgroup No . 02 Office of the Vice President .................. 35 - 39 Subgroup No . 03 Personal Papers ......................... 40 - 42 Record Group No . 02 Secretary and Treasurer ........................................ 43 - 153 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the Secretary and Treasurer ............ 44 - 151 Subgroup No . 02 Personal Papers ........................... 152 - 153 Record Group No . 03 Office of Finance and Accounts .................................. 155 - 197 Subgroup No . 01 Vice President and Comptroller . 156 - 158 Subgroup No. 02 General Auditor ............................ 159 - 191 Subgroup No . 03 Auditor of Disbursements ........................ 192 Subgroup No . 04 Auditor of Receipts ......................... 193 - 197 Record Group No . 04 Law Department ........................................ 199 - 237 Subgroup No . 01 General Counsel .......................... 200 - 225 Subgroup No . 02 -

Commuter Rail System On-Time Performance Report

COMMUTER RAIL SYSTEM ON-TIME PERFORMANCE REPORT October 2015 Division of Strategic Capital Planning December 2015 COMMUTER RAIL ON-TIME PERFORMANCE October 2015 This report presents an analysis of the October 2015 train delays as reported for Metra's eleven commuter rail lines. On-time is defined, for this analysis, as those regularly scheduled trains arriving at their last station stop less than six minutes behind schedule. Trains that are six minutes or more behind schedule, including annulled trains (trains that do not complete their scheduled runs), are regarded as late. “Extra” trains (trains added to handle special events but not shown in the regularly published timetables) are excluded from on-time performance calculations unless shown in special-event schedules that include all intermediate station stop times and are distributed publicly via Metra's website or on paper flyers. Cancelled (not annulled) trains and non-revenue trains are also excluded from on-time performance calculations. On-Time Performance Tables Table 1 presents the number of train delays by rail line and service period. During October 2015, Metra operated 17,717 scheduled trains, including scheduled “extras”, if any. 528 of these trains were delayed (late or annulled), representing an on-time performance rate of 97.0%. Table 2 lists on-time percentages by line for each month and year since 2010. Table 3 lists each train that was on time for less than 85% of its weekday runs in October 2015, in order of line, train, and dates delayed. The codes in the 'Delay Code' column of Table 3 are defined in Table 4 and shown sorted by delay-cause category and carrier designation in Table 5. -

Using Wheel Temperature Detector Technology to Monitor Railcar Brake System Effectiveness DTFR53-00-C-00012

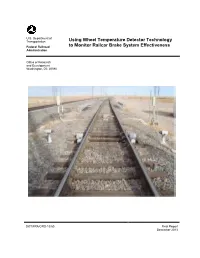

U.S. Department of Transportation Using Wheel Temperature Detector Technology Federal Railroad to Monitor Railcar Brake System Effectiveness Administration Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-13/50 Final Report December 2013 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Accident and Analysis Branch

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Accident and Analysis Branch Accident Investigation Report HQ-2013-08 New Jersey Transit Rail Operations (NJTR) Hoboken, NJ April 6, 2013 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report, including this one, made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. U.S. Department of Transportation FRA File #HQ-2013-08 Federal Railroad Administration FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT TRAIN SUMMARY 1. Name of Railroad Operating Train #1 1a. Alphabetic Code 1b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. New Jersey Transit Rail Operations NJTR 201304180 GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Name of Railroad or Other Entity Responsible for Track Maintenance 1a. Alphabetic Code 1b. Railroad Accident/Incident No. New Jersey Transit Rail Operations NJTR 201304180 2. U.S. DOT Grade Crossing Identification Number 3. Date of Accident/Incident 4. Time of Accident/Incident 4/6/2013 2:34 PM 5. Type of Accident/Incident Head On Collision 6. Cars Carrying 7. HAZMAT Cars 8. Cars Releasing 9. People 10. Subdivision HAZMAT 0 Damaged/Derailed 0 HAZMAT 0 Evacuated 0 Hoboken 11. Nearest City/Town 12. Milepost (to nearest tenth) 13. State Abbr. 14. County Hoboken 0 NJ HUDSON 15. Temperature (F) 16. Visibility 17. Weather 18. Type of Track 38ࡈ F Dark Clear Main 19. Track Name/Number 20. FRA Track Class 21. Annual Track Density 22. Time Table Direction (gross tons in millions) No.