The One Who Is Known Amy Hinman Grand Valley State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pet Or Food: Animals and Alimentary Taboos in Contemporary Children’S Literature

Beyond Philology No. 14/3, 2017 ISSN 1732-1220, eISSN 2451-1498 Pet or food: Animals and alimentary taboos in contemporary children’s literature JUSTYNA SAWICKA Received 8.07.2017, received in revised form 16.09.2017, accepted 21.09.2017. Abstract In books for pre-school and early school-age children (4-9 years of age) published in Poland between 2008 and 2014 it is possible to observe a new alimentary taboo. Though statistics show that we consume more meat than ever, we seem to be hiding this fact from the children. The animal is disconnected from the meat, which becomes just a thing we eat so that there is no need to consider animal suffering or to apply moral judgement to this aspect. The analysed books, written by Scandinavian, Spanish and American and Polish authors, do not belong to the mainstream of children’s literature, but, by obscuring the connection between the animal and the food we consume, they seem to testify to the problem with this aspect of our world that the adults – authors, educators and parents. Key words alimentary taboo, children’s literature, pre-school children, animal story, Scandinavian children’s literature 88 Beyond Philology 14/3 Uroczy przyjaciel czy składnik diety: Tabu pokarmowe we współczesnych książkach dla dzieci Abstrakt Książki dla dzieci w wieku przedszkolnym i wczesnoszkolnym (4-9 lat) wydane w Polsce w latach 2008-2014 są świadectwem istnienia nowego tabu pokarmowego. Chociaż statystyki wskazują, że obecnie jemy więcej mięsa niż kiedykolwiek wcześniej, coraz częściej ukrywamy przed dziećmi fakt zjadania zwierząt. Odzwierzęcamy mięso i czynimy je przedmiotem, wtedy bowiem nie musimy zasta- nawiać się nad cierpieniem zwierząt i nad moralnym osądem tego faktu. -

Solferino Soup Cucumber Soup Chicken Noodle Soup Barley Soup Tomato Noodle Soup Celery Cream Soup Corn Cream Soup Chickpeas Crea

Art'Impression Catering Sp.z o.o. 02-871 Warszawa ul. Karczunkowska 170 NIP: 951-212-18-98, Regon: 015822495 Tel: 603 817 107, e-mail: [email protected] www.ai-cateringwarszawa.pl/tbs MENU Monday 07.03.2016 Tuesday 08.03.2016 Wednesday 07.03.2016 Thursday 08.03.2016 Friday 09.03.2016 Solferino soup Cucumber soup Chicken noodle soup Barley soup Tomato noodle soup Soup Celery cream soup Corn cream soup Chickpeas cream soup with cumin Green beans cream soup Broccoli-cauliflower cream soup Grilled chicken fillet with cream-herbs Chicken kebab, tza-tziki dip, baked potato Pork roast with gravy, potato puree Chicken and vegetables shashlik, rice Mintaj fillet with vegetables, potato sauce, potato puree with herbs Meat Set I Boiled vegetables/baked beetroot salad Carrot salad with leek/red cabbage salad Green beans/ Cabbage salad with tomato Mix beans/ white cabbage salad Cauliflower/ iceberg lettuce with carrot with coriander with cranberry and sprouts Beef and poultry meatballs, tomato sauce, Chicken and vegetables risotto Meat dumplings, fried onion Pork goulash, barley Chicken strogonoff, buckwheat groats spaghetti Meat Set II Sliced beetroot in honey glaze/ Cabbage Green peas/ White cabbage salad with Broccoli/ Mix vegetables salad Corn/ red cabbage salad with apple Green peas/ carrot salad with orange salad with cucumber dill and olive Pasta with green vegetables in cream Italian focaccia with vegetables and Rice casserole with vegetables, cheese Vegetarian Lentil cutlet, remoulade sauce, barley Polenta with vegetables rattatouille -

Healthy Food. Russian Cuisine. Audio Exchange Project

ПРОЕКТНЫЕ ТЕХНОЛОГИИ HEALTHY FOOD. RUSSIAN CUISINE. AUDIO EXCHANGE PROJECT. LEVEL UPPER INTERMEDIATE Оборина Т. П., ГБОУ СОШ № 123, г. Москва Урок-видеопроект дискуссии “Audio-exchange I decided to record the students and send the tape project” по теме “Healthy food. Russian Cuisine” составлен to students in a non-Russian speaking country. для проведения в 10–11 классах. Planning Проведению урока предшествует большая подгото- At that point in the syllabus the topic was “Healthy вительная работа. Готовясь к уроку, учащиеся обсужда- Food”. I decided to encourage them to make a radio ют пройденную тему, готовят дополнительный матери- programme about traditions, Russian Cuisine. We ал. Такой урок расширяет и углубляет, систематизирует would send the cassette to another school and hope- знания учащихся, помогает развить речевые умения fully they would send recordings to us, too. The stu- с целью подготовки к государственному экзамену. dents would work together in pairs to answer ques- Класс делится на две группы. Одной группе учащих- tions about various special dishes and then we would ся предлагается выступить в роли студентов, расска- record the interviews. зывающих о традициях русской кухни, а вторая группа After the initial language input (topic-based vo- проводит интервью-расспрос у студентов, знающих рус- cabulary and appropriate structures) and practice, we скую кухню и её традиции. were able to complete the project within a week. Технологии: здоровьесбережения, коммуникатив- но-ориентированного дифференцированного обучения, PREPARATION педагогики сотрудничества, развития способностей уча- щихся, информационно-коммуникационные. Brainstorming Решаемые проблемы: систематизировать знания, I introduced the idea of the exchange project to the совершенствовать лексико-грамматические навыки students and told them about the radio programme. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Menu with Onion Crackers ������ � ������ � ������

ЗАВТРАКИ/BREAKFAST A LA CARTE ПН-ПТ/MO-FR 7:00-11:00; СБ-ВС/SA-SU 7:00-12:00 14:00 - 1:00 /APPETIZERS Ы/SOUPS Я/MEAT Ы/DESSERTS «К» К К «К ». ё К «ККК» Sliced frozen Salo with assorted sauces «» Sauerkraut “KimSchi” ё ёК Cococorn .....................................................................................350 р жж г .....................................................................................450 р “Kasha iz topora“. Green buckwheat porridge .....................................................................................350 р Тб г with porcini mushrooms and stewed beef cheeks К К- К КК .....................................................................................650 р К- «К» COCOCO CLASSICS Porcini mushroom cream-soup Creme brulee “Cameo” Pâtés with onion jam and hot rye bread жж courses must try menu with onion crackers КК КК .....................................................................................350 р .....................................................................................750 р .....................................................................................490 р 2900 р К “Kulebyaka”. Russian closed pie with rabbit and Sea buckthorn tart with carrot sorbet К К «К» pickled vegetables salad .....................................................................................350 р К ё К К .....................................................................................850 р 4- “Leningrad rassolnik” Beef tartare with -

Soups & Stews Cookbook

SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Soups & Stews Cookbook. SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Aash Rechte (Iranian Winter Noodle Soup) Adas Bsbaanegh (Lebanese Lentil & Spinach Soup) Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Almond Soup Artichoke & Mussel Bisque Artichoke Soup Artsoppa (Swedish Yellow Pea Soup) Avgolemono (Greek Egg-Lemon Soup) Bapalo (Omani Fish Soup) Bean & Bacon Soup Bizar a'Shuwa (Omani Spice Mix for Shurba) Blabarssoppa (Swedish Blueberry Soup) Broccoli & Mushroom Chowder Butternut-Squash Soup Cawl (Welsh Soup) Cawl Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Soup) Cawl Mamgu (Welsh Leek Soup) Chicken & Vegetable Pasta Soup Chicken Broth Chicken Soup Chicken Soup with Kreplach (Jewish Chicken Soup with Dumplings) Chorba bil Matisha (Algerian Tomato Soup) Chrzan (Polish Beef & Horseradish Soup) Clam Chowder with Toasted Oyster Crackers Coffee Soup (Basque Sopa Kafea) Corn Chowder Cream of Celery Soup Cream of Fiddlehead Soup (Canada) Cream of Tomato Soup Creamy Asparagus Soup Creamy Cauliflower Soup Czerwony Barszcz (Polish Beet Soup; Borsch) Dashi (Japanese Kelp Stock) Dumpling Mushroom Soup Fah-Fah (Soupe Djiboutienne) Fasolada (Greek Bean Soup) Fisk och Paprikasoppa (Swedish Fish & Bell Pepper Soup) Frijoles en Charra (Mexican Bean Soup) Garlic-Potato Soup (Vegetarian) Garlic Soup Gazpacho (Spanish Cold Tomato & Vegetable Soup) 2 SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food -

A Little Book of Soups: 50 Favourite Recipes Free

FREE A LITTLE BOOK OF SOUPS: 50 FAVOURITE RECIPES PDF New Covent Garden Soup Company | 64 pages | 01 Feb 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9780752265766 | English | London, United Kingdom A Little Book of Soups by New Covent Garden Soup Company | Waterstones Unfortunately we are currently unable to provide combined shipping rates. It has a LDPE 04 logo on it, which means that it can be recycled with other soft plastic such as carrier bags. We encourage you to recycle the packaging from your World of Books purchase. If ordering within the UK please allow the maximum 10 business days before contacting us with regards to delivery, once this has passed please get in touch with us so that we can help you. We are committed to ensuring each customer is entirely satisfied with their puchase and our service. If you have any issues or concerns please contact our customer service team and they will be more than happy to help. World of Books Ltd was founded inrecycling books sold to us through charities either directly or indirectly. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. We now ship over two million orders each year to satisfied customers throughout the world and take great pride in our prompt delivery, first class customer service and excellent feedback. While we do our best to provide good quality books A Little Book of Soups: 50 Favourite Recipes you to read, there is no escaping the fact that it has been owned and read by someone else before you. -

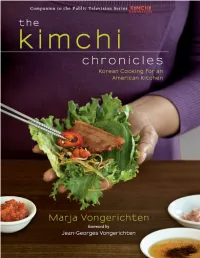

The Kimchi Chronicles Television Show, but Also with This Cookbook

This book is dedicated to my two mothers, one who gave me life and the other who helped me live it. Contents Foreword by Jean-Georges Vongerichten Introduction Pantry: My Korean-American Kitchen One: Kimchi and Banchan Two: Vegetables and Tofu Three: Korean Barbecue Four: Meat and Poultry Five: Fish and Shellfish Six: Rice and Noodles Seven: Cocktails, Anju, and Hangover Cures Eight: A Little Something Sweet Acknowledgments Resources Photo Credits Index Foreword hen I was growing up in Alsace, France, my room was just above the Wkitchen. My mother and grandmother used to prepare meals for the family’s coal company employees. Big pots of traditional Alsatian foods bubbled below, and the scent would just waft up into my room. I loved watching them cook, and eventually I became the family palate—I’d taste the food and tell my mom what was missing: a little salt here, a little butter there. One day, I realized that I wanted to cook for a living, and I was lucky enough to apprentice with some of the greatest chefs in France. I was trained in classical French techniques, which were firmly based in stocks that took hours to make and were heavy on the butter and cream. When I was 23, I moved to Bangkok to work at the Mandarin Oriental. It was the first time that I had ever traveled that far from home. On my way to the hotel from the airport, I stopped at a food stand on the side of the street and had a simple soup that changed my life. -

Soup Bagels Almonds

Jan/Feb/Mar 2021 The English Language Food Magazine For Portugal Lovers Everywhere SOUP BAGELS ALMONDS DO YOU SPEAK +++ T HE CHARM AND HISTORY OF CHOCOLATE?? BEAUTIFUL BOYFRIEND SCARVES TABLE OF CONTENTS IN EVERY ISSUE FEATURES 10 Wine Vines Food For Thought Black Sheep Lisboa/ 7 RealPortugueseWine.com Lucy Pepper, Eat Portugal 13 Not From Around Here Av’s Pastries & Catering The Secret Ingredient Is Always Chocolate 21 15 Let’s Talk Chocolate Master PracticePortuguese.com Pedro Martins Araújo, Vinte Vinte Chocolate 17 My Town Dylan Herholdt, Portugal Soup’s On: the Simple Life Podcast/ The Definitive Guide To 28 Portugal Realty Portugal’s Soup Scene 19 Portuguese Makers Amass. Cook. Lenços dos Namorados/ Aliança Artesanal Product Spotlight 38 52 Perspective Portuguese Rice David Johnson Guest Artist The Legend of the 12 41 Eileen McDonough, Almond Blossom Lisbon Mosaic Studio AB Villa Rentals Fado: The Sonority 43 Of Lisbon getLISBON Reader Recipe 45 Vivian Owens >>> Turn to pages 48-50 for Contributors/Recipe List/What’s Playing in Your Kitchen<<< FROM MY COZINHA The local food and flavor magazine for I don’t know about you, but these last several months I’ve been doing a lot of English-speaking Portugal traveling…in my mind. I catch myself lovers everywhere! staring into space, daydreaming, reliving some of my excellent adventures and planning an extensive Relish Portugal is published four multi-country train excursion across times a year plus two special Europe. I see friends on Zoom and, in editions. reality, my outside exploits are no more exotic than a trip to the grocery store or All rights reserved. -

Tv Pg 01-04-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, January 4, 2011 7 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening January 4, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC No Ordinary Family V Detroit 1-8-7 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS Live to Dance NCIS Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Glee Million Dollar Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC Demolition Man Demolition Man Crocodile Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike Animals Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET American Gangster The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show State 2 Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Matchmaker Matchmaker The Fashion Show Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local The Dukes of Hazzard The Dukes of Hazzard Canadian Bacon 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Daily Colbert Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Futurama Local 9 NBC-KUSA 37 USA 65 We DISC Local Local Dirty Jobs -

ELLISTON-STANLEY FUNERAL HOME Rep

Page 2, The Falmouth Outlook, January 4, 2011 Calendar Community Forum on Bed Bugs Looking Back Through the Years January 11 at Pendleton High The Pendleton County county and school announce- Cooperative Extension Service ments/website and everything 25 Years Ago 50 Years Ago 75 Years Ago 100 Years Ago and Three Rivers District Health will done to make sure the pub- Department will be holding a lic knows about the upcoming January 3, 1986 January 6, 1961 January 10, 1936 January 4, 1911 Community Forum/Informa- meeting. The Shonert family dy- The Pendleton Wildcats The total bonded indebted- Ben Rice sold 23 nice geese tional meeting on bed bugs will Topics that will be addressed nasty of 78 years is broken. The walked off with their second ness of the City of Falmouth at to Bert Littleton for 65 cents be held at 7 p.m. January 11 at the meeting: Falmouth Outlook, weekly straight first place trophy in the the close of business December each. with a snow date held for · What are bed bugs newspaper serving the Falmouth Invitational Tournament. The 31, 1935, stood at $14,000. W.H. Pribble of Mt. Auburn January 18. The program will be · How do we prevent getting and Pendleton County commu- first night, Harrison defeated The Supreme Court of the has purchased a new milk held at Pendleton County High them nities since 1907, has been sold Falmouth 53-52 in a squeaker United States handed down the wagon. School in the auditorium. · Now that we have them, to an Ohio-based newspaper and Pendleton in the second most important and far-reaching Frank Works has purchased Information on the upcom- what do we do group. -

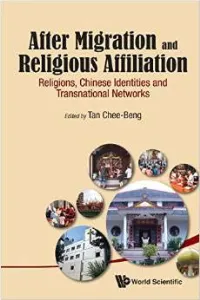

THE PERUVIAN CHINESE COMMUNITY Isabelle Lausent-Herrera

b1751 After Migration and Religious Affiliation: Religions, Chinese Identities and Transnational Networks 8 BETWEEN CATHOLICISM AND EVANGELISM: THE PERUVIAN CHINESE COMMUNITY Isabelle Lausent-Herrera First Conversions to Catholicism Acuam1 must have been between 9 and 14 years old2 when he by Dr. Isabelle Lausent-Herrera on 09/04/14. For personal use only. debarked in Peru in 1850 from one of the first ships bringing in After Migration and Religious Affiliation Downloaded from www.worldscientific.com 1 The existence of this boy is known thanks to a document written in 1851 by José Sevilla, associate of Domingo Elías (Lausent-Herrera, 2006: 289). In the report “Representación de la Empresa a la Honorable Cámara de Senadores. Colonos Chinos”, Biblioteca Nacional de Lima (BNL), Miscelanea Zegarra, XZ-V58-1851, folio 37-38, José Sevilla tried to convince the Peruvian Government that the arrival in Peru of a great number of Chinese coolies was a good idea. For this, he reproduced the letters of satisfaction sent to him by all the hacendados, 185 bb1751_Ch-08.indd1751_Ch-08.indd 118585 224-07-20144-07-2014 111:10:101:10:10 b1751 After Migration and Religious Affiliation: Religions, Chinese Identities and Transnational Networks 186 After Migration and Religious Affiliation coolies for the great2sugar haciendas, the cotton plantations and the extraction of guano on the Chincha Islands. Since the year before, Domingo Elias and José Sevilla had started to import this new work- force destined for the hacendados to replace the Afro-Peruvians freed from slavery. Aiming to have a law voted to legalize this traffic between China and Peru, José Sevilla published a report investigat- ing the satisfaction of the first buyers.