Multilingual the Hague: Municipal Language Policy, Politics, and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IADD BANA Braille Standards

Let Your Fingers Do The Talking: Braille on Folding Cartons in cooperation with February 2012 (Revision 1) 1 Preface 4 History of braille in folding carton production and references 2 Traditional Braille Cell and Braille Characters 5 Letters, punctuation marks, numbers, special characters 3 Standardization 7 Dot matrix, dot diameters, dot spacing, character and line spacing, embossing height, positioning the braille message 4 Technical Requirements 8 Functional and optical characteristics, material selection 5 Fabrication 9 Braille embossing, positioning of braille, amount of text 6 Prepress and Quality Assurance 12 Artwork files and print approvals, quality assurance 7 Conclusion 14 3 1 Preface In 1825, Frenchman Louis Braille (1809-1852) invented a reading system for the blind through which the alphabet, numbers and punctuation marks were represented in a tangible form via a series of raised dots. The braille system established itself internationally and is now in use in all languages. While A to Z is standardized, there are, of course, special characters which are unique to local languages. The requirement for braille on pharmaceutical packaging stems from the European Directive 2004/27/EC – amending Directive 2001/83/EC (community code to medicinal products for human use). This Directive includes changes to the label and package leaflet requirements for pharmaceuticals (which will not be discussed in this booklet). It requires pharmaceutical cartons to show the name of the medicinal products and, if need be, the strength in braille format. The influence of the European Directive is having an increasing impact on Canada, USA and other countries worldwide through the pharmaceutical packaging companies that produce for or market at an international level. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

Social Democratic Parties and Trade Unions: Parting Ways Or Facing the Same Challenges?

Social Democratic Parties and Trade Unions: Parting Ways or Facing the Same Challenges? Silja Häusermann, Nadja Mosimann University of Zurich January 2020, draft Abstract Both social democratic parties and trade unions in Western Europe have originated from the socio-structural emergence, political mobilization and institutional stabilization of the class cleavage. Together, they have been decisive proponents and allies for the development of so- cial, economic and political rights over the past century. However, parties of the social demo- cratic left have changed profoundly over the past 30 years with regard to their membership composition and – relatedly – their programmatic supply. Most of these parties are still strug- gling to decide on a strategic-programmatic orientation to opt for in the 21st century, both regarding the socio-economic policies they put to the forefront of their programs, as well as regarding the socio-cultural stances they take (and the relative weight of these policies). Since their strategic calculations depend, among others things, on the coalitional options they face when advancing core political claims, we ask if trade unions are still "natural" allies of social democratic parties or if they increasingly part ways both regarding the socio-demographic composition of constituencies as well as the political demands of these constituencies. We study this question with micro-level data on membership composition from the Euroba- rometer and the European Social Survey from 1989 to 2014 as well as data on policy prefer- ences from the European Social Survey from 2016 while focusing on the well-known welfare regimes when presenting and discussing the results. -

Braille in Mathematics Education

Masters Thesis Information Sciences Radboud University Nijmegen Braille in Mathematics Education Marc Bitter April 4, 2013 Supervisors IK183 Prof.Dr.Ir. Theo van der Weide Dr. Henny van der Meijden Abstract This research project aimed to make improvements to the way blind learners in the Netherlands use mathematics in an educational context. As part of this research, con- textual research in the field of cognition, braille, education, and mathematics was con- ducted. In order to compare representations of mathematics in braille, various braille codes were compared according to set criteria. Finally, four Dutch mathematics curricula were compared in terms of cognitive complexity of the mathematical formulas required for the respective curriculum. For this research, two main research methods were used. A literature study was conducted for contextual information regarding cognitive aspects, historic information on braille, and the education system in the Netherlands. Interviews with experts in the field of mathematics education and braille were held to relate the contextual findings to practical issues, and to understand why certain decisions were made in the past. The main finding in terms of cognitive aspects, involves the limitation of tactile and auditory senses and the impact these limitations have on textual aspects of mathematics. Besides graphical content, the representation of mathematical formulas was found to be extremely difficult for blind learners. There are two main ways to express mathematics in braille: using a dedicated braille code containing braille-specific symbols, or using a linear translation of a pseudo-code into braille. Pseudo-codes allow for reading and producing by sighted users as well as blind users, and are the main approach for providing braille material to blind learners in the Netherlands. -

Using Faith to Exclude

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository 5 USING FAITH TO EXCLUDE THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN DUTCH POPULISM Stijn van Kessel 1 Religion has played a crucial role in the formation of the Dutch party system, and party competition in the first decades after World War II was, to a consid- erable degree, still determined by the religious denomination of voters. Most religious voters were loyal to one of the three dominant ‘confessional’ parties: the large Catholic People’s Party (KVP) or one of the two smaller Protestant parties (ARP and CHU).2 Until the parliamentary election of 1963, the com- bined vote share of the three dominant confessional parties was around 50 per cent. Most secular voters, on the other hand, turned either to the Labour Party (PvdA), representing the working class, or the Liberal Party (VVD), repre- senting the secular middle class. The fact that voting behaviour was rather predictable resulted from the fact that Dutch parties and the most significant religious and social groups—arguably with the exception of the secular middle class and the VVD—were closely aligned.3 One aspect of this ‘pillarisation’ of society was that the electorate voted largely along traditional cleavage lines of religion and social class. 61 SAVING THE PEOPLE The dividing lines between the social groups gradually evaporated, in part due to the secularisation of society since the 1960s. Except for the secular middle class, the social background of the electorate continued to determine voting patterns quite predictably in the following decades, but by the turn of the twenty-first century the explanatory power of belonging to a traditional pillar had faded to a large extent.4 What is more, as Dutch society became more secularised, the level of electoral support for the three dominant confes- sional parties began to decline. -

The Dutch Parliamentary Elections: Outcome and Implications

CRS INSIGHT The Dutch Parliamentary Elections: Outcome and Implications March 20, 2017 (IN10672) | Related Author Kristin Archick | Kristin Archick, Specialist in European Affairs ([email protected], 7-2668) The March 15, 2017, parliamentary elections in the Netherlands garnered considerable attention as the first in a series of European contests this year in which populist, antiestablishment parties have been poised to do well, with possibly significant implications for the future of the European Union (EU). For many months, opinion polls projected an electoral surge for the far-right, anti-immigrant, anti-EU Freedom Party (PVV), led by Geert Wilders. Many in the EU were relieved when the PVV fell short and the center-right, pro-EU People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), led by incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte, retained its position as the largest party in the Dutch parliament. Several commentators suggest that the Dutch outcome may be a sign that populism in Europe and "euroskeptism" about the EU are starting to lose momentum, but others remain cautious about drawing such conclusions yet. Election Results The Dutch political scene has become increasingly fragmented; 28 political parties competed in the 2017 elections for the 150-seat Second Chamber, the "lower"—but more powerful—house of the Dutch parliament. Concerns about immigration, national identity, and the role of Islam in the Netherlands (approximately 5.5% of the country's 17 million people are Muslim) dominated the campaigning. The VVD came in first, with 33 seats, but lost roughly one-fifth of its previous total. The PVV finished second, with 20 seats, making modest gains on its 2012 election results but not performing as well as expected. -

Hanke, Peter, Ed. International Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 258 389 EC 172 909 AUTHOR Cylke, Frank Kurt, Ed.; Hanke, Peter, Ed. TITLE International Directory of Libraries and Production Facilities for the Blind. INSTITUTION International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, London (England).; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. SPONs _3ENCY United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Paris (France). PUB DATE 84 CONTRACT UNESCO-340029 NOTE 109p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE mF01/PCOS Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Blindness; *Braille; International Programs; Physical Disabilities; Reading Materials; Sensory Aids; *Special Libraries; *Talking Books ABSTRACT World-wide in scope, this directory lists organizations producing braille or Talking Books, maintaining braille libraries, and exchanging resources with organizations serving blind or handicapped people. The directory is arranged in seven geographical sections: Africa, Asia, Australia (including Oceania), Europe (including U.S.S.R.), Middle East (northern Africa and the eastern Mediterranean countries), North' America, and South America (including Central America and the Caribbean). Countries are arranged- alphabetically within these seven sections and individual organizations alphabetically within their countries. Information about each organization includes five parts: braille production, braille distribution, Talking Books production, Talking Books distribution, and general information. -

SOD Netherlands Final

SoD Summary The State of Our Democracy1 Democracy Program. Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, The Hague. 2006. 1 This summary is based on the report “The State of our Democracy” which reflects the situation in the Netherlands in 2006. Developments since then have not been taken into account. 1 The assassination of Pim Fortuyn and the aftermath of the 2002 parliamentary elections generated political turbulence and a vibrant public debate on the functioning the political institutions and practices in Netherlands. This assessment was initiated by the Government of the Netherlands to record the situation and to promote discussion on Dutch democracy and the need for reform. Key Recommendations The practice of committing offenders to psychiatric clinics (also known as TBS-System) for enforced treatment must be improved to ensure that proper protections are in place. Freedom of speech in the Netherlands must be protected and safeguarded. The socio-economic conditions of non-western ethnic minorities must be improved. Political parties have to become more open and inclusive, in particular for younger Dutch citizens. Cabinet should provide more information on Government policies in order to increase its accountability. Non-departmental public bodies must become more transparent and accountable. Effective control over autonomous regional police departments must be introduced. Citizens and organizations should become effectively involved in policy preparation. More transparent appointment procedures in public administration will increase political confidence. 2 The Four Pillars and the Origins: Why perform a SoD assessment assessment? The assassination of Pim Citizenship and the Constitutional State Fortuyn and the aftermath of the 2002 parliamentary Nationality and Public Spirit elections generated political turbulence and a vibrant Dutch nationality is granted to every person with at least one Dutch parent, or anyone born in Dutch territory and who has not public debate on the acquired another nationality by the age of five years. -

Of Incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN THE NETHERLANDS 17th March 2021 Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, European Elections monitor (VVD), wins the general elections for a fourth consecutive term in office Corinne Deloy Results The liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy saw its number of elected members almost halved: 8 (VVD) of outgoing Prime Minister Mark Rutte has won seats (-6). the Dutch general elections for the fourth time in a row. As in 2017, the decline of the left is mainly due to the The party won 34 seats in the House of States General, PvdA, which has long been the leader of the left and is not the lower house of parliament (+1 compared to the growing. As Cas Mudde, a professor at the University of previous legislative elections of 15 March 2017). Due to Georgia in the United States, writes, "the Dutch Labour the health situation, the elections were held over three Party is suffering 'pasokification', whereby the influence days, between 15 and 17 March, so that vulnerable of social democratic parties declines with each election people could have the time and room necessary to as with the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) in perform their civic duty. People over 70 were invited to Greece or the Socialist Party (PS) in France.” vote by post. "Voters in the Netherlands have given my party a massive vote of confidence. I am very proud of Geert Wilders' right-wing populist Party for Freedom this," said Mark Rutte after the results were announced, (PVV) came third with 17 MPs (-3). "One thing is certain, adding "proud of what we have achieved over the last the stronger we are, the more people will vote for my ten years in the Netherlands.” party, the harder it will be to exclude us," Geert Wilders repeated during the campaign. -

Fleur De Beaufort and Patrick Van Schie Interpret the Results of The

The Dutch elections and ‘populism’ www.worldcommercereview.com Fleur de Beaufort and Patrick van Schie interpret the results of the Dutch elections, and consider the growth in the support for the alternative 'populist' parties The background to the elections in the Netherlands In March 2021 the scheduled elections were held for the Second Chamber, which is the more important of the two chambers comprising the Dutch parliament. As many as 37 parties sought a seat in the new Second Chamber. The elections were remarkable for various reasons and the run-up to them proceeded more messily than ever before. On the left, where three political parties – the Partij van de Arbeid [Labour Party] (PvdA), GroenLinks [Green-Left Party], and the Socialistische Partij [Socialist Party] have been talking in vain about combining their forces for many years now, they again beat about the bush as is customary in relation to the contentious issue of ‘greater cooperation’. On the right, conflicts ensued in the weeks preceding the elections, which resulted in splits and the birth of new competitors. In the meantime, the existing government coalition of four centre-right and centre-left parties (the third cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte) fell on 15 January in the wake of a social allowance affair which saw the Tax and Customs Administration office wrongly accuse and prosecute the recipients of childcare allowances as frauds over a lengthy period of time. The fall of the Rutte III government was accompanied by the demise of the odd key political player and the social democrats were urgently compelled to seek a new leading candidate (because their current one had been www.worldcommercereview.com responsible in his capacity as a minister in the previous government), while others explicitly secured the ongoing support of their rank and file, and remained. -

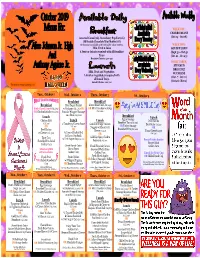

October 2019 Menus For

October 2019 WEEK ONE: CHARRO BEANS Menus For: (Oct 14 - Oct 18) Assorted Cereal (1G), Strawberry Pop Tart(1G) OR Double Chocolate Mini Muffin (1G) Grahams are available with each of the above entrées. WEEK TWO: Milk, Fruit & Juice GOLDEN CORN Alice Johnson Jr. High A Fruit or Juice is required with all Breakfast (Sept 30 - Oct 4) Trays (Oct 21 - Oct 25) Breakfast Calories: 400-550 And WEEK THREE: STEAMED Anthony Aguirre Jr. BROCCOLI Milk, Fruit and Vegetables. W/CHEESE A Fruit or Vegetable is required with (Oct. 7 - Oct 11) all Lunch Trays. Lunch Calories: 600-700 (Oct 28 - Nov 1) This institution is an equal opportunity provider. Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Fruit Yogurt Parfait Glazed Sweet Roll (Cal./230) Pink Glazed Donut (Cal./289) w/Grahams (Cal./281) OR OR Mini Pancakes w/Syrup OR Chicken Kolache (Cal./180) (Cal./260) Pancake Wrapped Sausage on a Stick (Cal./210) Breakfast Lunch Egg & Sausage Lunch Chicken Melt Lunch Lunch Pork Carnita (Cal./331) 2 Tamales w/Cheese Sauce Gold Kist Crispy Chicken Breakfast Taco (Cal./296) OR Turkey Sausage Enchiladas (Cal./409) OR (Cal./390) Nuggets w/Macaroni & OR OR Breakfast Pizza (Cal./210) Beef Nachos Cheese (Cal./428) Texas Cheeseburger w/Cheese (Cal./328) ½ Toasted Turkey Deli OR (Cal./385) & Cheese Sandwich Gold Kist Spicy Chicken Tater Tots w/Trix Yogurt Cup (Cal./251) Sandwich (Cal./376) Emoji Potato Smiles Shredded Pico Salad Golden Corn Burger Salad Sweet Carrot Coins Fresh Flavored Carrots Golden Corn Strawberry Milk Charro Beans Seasoned Waffle Fries will be available. Golden Corn