Is There Such Thing As a Language?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IADD BANA Braille Standards

Let Your Fingers Do The Talking: Braille on Folding Cartons in cooperation with February 2012 (Revision 1) 1 Preface 4 History of braille in folding carton production and references 2 Traditional Braille Cell and Braille Characters 5 Letters, punctuation marks, numbers, special characters 3 Standardization 7 Dot matrix, dot diameters, dot spacing, character and line spacing, embossing height, positioning the braille message 4 Technical Requirements 8 Functional and optical characteristics, material selection 5 Fabrication 9 Braille embossing, positioning of braille, amount of text 6 Prepress and Quality Assurance 12 Artwork files and print approvals, quality assurance 7 Conclusion 14 3 1 Preface In 1825, Frenchman Louis Braille (1809-1852) invented a reading system for the blind through which the alphabet, numbers and punctuation marks were represented in a tangible form via a series of raised dots. The braille system established itself internationally and is now in use in all languages. While A to Z is standardized, there are, of course, special characters which are unique to local languages. The requirement for braille on pharmaceutical packaging stems from the European Directive 2004/27/EC – amending Directive 2001/83/EC (community code to medicinal products for human use). This Directive includes changes to the label and package leaflet requirements for pharmaceuticals (which will not be discussed in this booklet). It requires pharmaceutical cartons to show the name of the medicinal products and, if need be, the strength in braille format. The influence of the European Directive is having an increasing impact on Canada, USA and other countries worldwide through the pharmaceutical packaging companies that produce for or market at an international level. -

Braille in Mathematics Education

Masters Thesis Information Sciences Radboud University Nijmegen Braille in Mathematics Education Marc Bitter April 4, 2013 Supervisors IK183 Prof.Dr.Ir. Theo van der Weide Dr. Henny van der Meijden Abstract This research project aimed to make improvements to the way blind learners in the Netherlands use mathematics in an educational context. As part of this research, con- textual research in the field of cognition, braille, education, and mathematics was con- ducted. In order to compare representations of mathematics in braille, various braille codes were compared according to set criteria. Finally, four Dutch mathematics curricula were compared in terms of cognitive complexity of the mathematical formulas required for the respective curriculum. For this research, two main research methods were used. A literature study was conducted for contextual information regarding cognitive aspects, historic information on braille, and the education system in the Netherlands. Interviews with experts in the field of mathematics education and braille were held to relate the contextual findings to practical issues, and to understand why certain decisions were made in the past. The main finding in terms of cognitive aspects, involves the limitation of tactile and auditory senses and the impact these limitations have on textual aspects of mathematics. Besides graphical content, the representation of mathematical formulas was found to be extremely difficult for blind learners. There are two main ways to express mathematics in braille: using a dedicated braille code containing braille-specific symbols, or using a linear translation of a pseudo-code into braille. Pseudo-codes allow for reading and producing by sighted users as well as blind users, and are the main approach for providing braille material to blind learners in the Netherlands. -

Multilingual the Hague: Municipal Language Policy, Politics, and Practice

Multilingual The Hague: Municipal language policy, politics, and practice Anne-Mieke M. M. Thieme Leiden University January 2020 Supervisor: Prof. I. M. Tieken-Boon van Ostade Second reader: Dr. D. Smakman Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been what it is today without the help of many people. First of all, I would like to express my greatest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. Her helpful feedback, enthusiasm, and insights encouraged me to get the most out of my Research Master’s thesis project. I am extremely thankful that she was my thesis supervisor. I would also really like to thank Dr Eduardo Alves Vieira for discussing my thesis ideas with me and giving useful advice about which directions I could consider. I am also grateful to the audience at Anéla’s 2019 Study Day about Multilingualism in Education and Society for their interesting comments. I am incredibly indebted to Peter Sips, Lodewijk van Noort, and Frank Welling of the municipality of The Hague, who kindly talked to me and gave me insight into municipal language policy. Without their help, this thesis would have an empty shadow in comparison to what it is now. They showed me how relevant the topic was, inspiring me to dig deeper and push further. Thank you so much, Peter, Lodewijk, and Frank. Lastly, I would like to thank my family and friends for the unconditional support they gave me, for listening to my ideas, and asking helpful questions. I am forever grateful that they were there for me along the way. -

Hanke, Peter, Ed. International Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 258 389 EC 172 909 AUTHOR Cylke, Frank Kurt, Ed.; Hanke, Peter, Ed. TITLE International Directory of Libraries and Production Facilities for the Blind. INSTITUTION International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, London (England).; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. SPONs _3ENCY United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Paris (France). PUB DATE 84 CONTRACT UNESCO-340029 NOTE 109p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE mF01/PCOS Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Blindness; *Braille; International Programs; Physical Disabilities; Reading Materials; Sensory Aids; *Special Libraries; *Talking Books ABSTRACT World-wide in scope, this directory lists organizations producing braille or Talking Books, maintaining braille libraries, and exchanging resources with organizations serving blind or handicapped people. The directory is arranged in seven geographical sections: Africa, Asia, Australia (including Oceania), Europe (including U.S.S.R.), Middle East (northern Africa and the eastern Mediterranean countries), North' America, and South America (including Central America and the Caribbean). Countries are arranged- alphabetically within these seven sections and individual organizations alphabetically within their countries. Information about each organization includes five parts: braille production, braille distribution, Talking Books production, Talking Books distribution, and general information. -

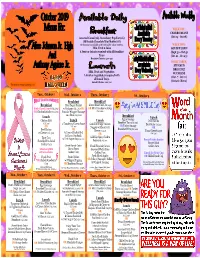

October 2019 Menus For

October 2019 WEEK ONE: CHARRO BEANS Menus For: (Oct 14 - Oct 18) Assorted Cereal (1G), Strawberry Pop Tart(1G) OR Double Chocolate Mini Muffin (1G) Grahams are available with each of the above entrées. WEEK TWO: Milk, Fruit & Juice GOLDEN CORN Alice Johnson Jr. High A Fruit or Juice is required with all Breakfast (Sept 30 - Oct 4) Trays (Oct 21 - Oct 25) Breakfast Calories: 400-550 And WEEK THREE: STEAMED Anthony Aguirre Jr. BROCCOLI Milk, Fruit and Vegetables. W/CHEESE A Fruit or Vegetable is required with (Oct. 7 - Oct 11) all Lunch Trays. Lunch Calories: 600-700 (Oct 28 - Nov 1) This institution is an equal opportunity provider. Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Fruit Yogurt Parfait Glazed Sweet Roll (Cal./230) Pink Glazed Donut (Cal./289) w/Grahams (Cal./281) OR OR Mini Pancakes w/Syrup OR Chicken Kolache (Cal./180) (Cal./260) Pancake Wrapped Sausage on a Stick (Cal./210) Breakfast Lunch Egg & Sausage Lunch Chicken Melt Lunch Lunch Pork Carnita (Cal./331) 2 Tamales w/Cheese Sauce Gold Kist Crispy Chicken Breakfast Taco (Cal./296) OR Turkey Sausage Enchiladas (Cal./409) OR (Cal./390) Nuggets w/Macaroni & OR OR Breakfast Pizza (Cal./210) Beef Nachos Cheese (Cal./428) Texas Cheeseburger w/Cheese (Cal./328) ½ Toasted Turkey Deli OR (Cal./385) & Cheese Sandwich Gold Kist Spicy Chicken Tater Tots w/Trix Yogurt Cup (Cal./251) Sandwich (Cal./376) Emoji Potato Smiles Shredded Pico Salad Golden Corn Burger Salad Sweet Carrot Coins Fresh Flavored Carrots Golden Corn Strawberry Milk Charro Beans Seasoned Waffle Fries will be available. Golden Corn -

Chapter 6, Writing Systems and Punctuation

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

A HISTORICAL STUDY of HANDWRITING and DRAWING By

THE HANDS OF JOHANNES WHISLER: A HISTORICAL STUDY OF HANDWRITING AND DRAWING by Matthew Capezzuto Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith M. Burton, Sponsor Professor Michael Hanchett Hanson Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date February 10, 2021 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2021 ABSTRACT THE HANDS OF JOHANNES WHISLER: A HISTORICAL STUDY OF HANDWRITING AND DRAWING Matthew Capezzuto The Book of Arithmetic Problems of Johannes Whisler (1814-1815), a mathematics exercise book in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum in New York City, is the central object of this study. This handwritten and illuminated book, created by a young Pennsylvania German man in the early 19th century, prompts a reevaluation of handwriting and doodling, with implications for the present era. The author documents the biographical and sociocultural circumstances surrounding the creation of Whisler’s cyphering book through primary and secondary historical research and applies Glăveanu’s theory of distributed creativity to describe the book as a creative process that emerged among people and objects, and across time. As direct indices of immediate actions, handwriting and doodling emerge in moment-to-moment action, even as these actions are embedded in longer periods of developmental and historical change; the author documents Whisler’s handwriting flourishes and doodles and describes the particular qualities of these mark making activities with reference to the sociocultural context in which they appear, Werner’s theories regarding the physiognomic perception of symbols, and Stern’s theory of vitality forms. -

Appendix I Translation Languages

Appendix I Translation Languages Cree - Kinyarwanda Abkhaz Mushkegowuk Gonja (Rwanda, Ruanda) Nepali Slovenian Gourmanchema Acholi Cree - North East (Gurma, Gourma) Kirghiz Niuean Soga Adangme Cree - Plains Grebo Kiribati Norwegian Somali Adyghe Cree - South East Greek Kirundi Nuer Soninke Afrikaans Cree - Swampy Gujarati Koho Nuristani Sorbian - Lower Akateko Cree - Woodlands Gwichin Komi - Permyak Nyanja (Malawi) Sorbian - Upper Creole - Guyanese Albanian English Hakka Komi - Zyrian Nzema Sotho Creole - Haitian Altay French Harari Kongo Occitan Sotho - Northern Creole - Jamaican Ojibwa (Ojibwe, Amharic English (Patois) Hassaniyya Konkani Ojibway) Spanish Spanish - Latin Anishinaabemowin Croatian Hausa Korean Oji-Cree America Oji-Cree - Arabic Cypriot Greek Hawaiian Koryak Anishinini Spanish - Spain Arabic - Moroccan Czech Hebrew Kosraean Oriya Sunda Susu (Sose, Soso) Arabic - Sudanese Dagaare Hiligaynon Kpelle Oromiffa (Of Guinea) Krio (Creole - Sierra Leone Aramaic Dagbani Hindi English) Oromo Swahili - Kibajuni Armenian Dakota Hindustani Krobo Oshiwambo Swahili (Kiswahili) Armenian - Eastern Dangme - Krobo Hiri Motu Kurdish - Badini Ossetic Swazi Armenian - Kurdish - Western Danish Hmong Kurmandji Otjiherero (Herero) Swedish Asante Twi (Asanti, Ashante) - Hmong - Daw (Of Akan Dari Laos, China) Kurdish - Sorani Palauan Tagalog (Filipino) Hmong - Do (Of Assamese Dene (Chipewyan) Vietnam) Kutchi Pamiri Tahitian Hmong - Njua (Green) (Of Laos, Taishan (Toisan, Assyrian Dewoin China) Ladin Pampango Hoisan) Lamnso' (Banso', Atikamekw Dhivehi -

(SIRS) Manual School Year

New York State Student Information Repository System (SIRS) Manual Reporting Data for the 2010–11 School Year October 15, 2010 Version 6.0 The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Information and Reporting Services Albany, New York 12234 Revision History Revision History Version Date Revisions Initial Release. Please pay particular attention to revisions to guidance on: • Role of District Data Coordinator. • New race/ethnicity reporting rules. • New teacher/course reporting rules. • Implementation of new federal rules (one-day enrollment criterion, assignment of grade 9 entry date for ungraded students with a disability, and outcome status determinations for court placements of incarcerated students) for 2006 (non-accountability) and 2007 total cohort graduation October 15, 6.0 rate reporting purposes. 2010 • New Reason for Ending Enrollment Code 8338 – Incarcerated student, no participation in a program culminating in a regular diploma. • New test accommodation codes. • Deleted CTE Codes. • Student Grades, Staff Snapshot, Course, and Marking Period Templates. • Component Retests, SLPs, Reading First, and Grades 5 & 8 NYSTP and NYSAA Social Studies no longer available. ii Student Information Repository System Manual for 2010–11 Version 6.0 Table of Contents Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................1 New York State Education Department E-mail Queries ..........................................................................3 -

The Impact of Open Licensing on the Early Reader Ecosystem

THE IMPACT OF OPEN LICENSING ON THE EARLY READER ECOSYSTEM Neil Butcher and Sarah Hoosen, Neil Butcher and Associates Lisbeth Levey, Consultant, ICT for Development Derek Moore, Weblearning The Impact of Open Licensing on the Early Reader Ecosystem can be found at: http://www.nba.co.za/impact-open-licensing-early-reader-ecosystem Funded by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation http://www.hewlett.org July, 2016 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported Licence. You are free to share and adapt this work, but you must give appropriate credit and indicate if changes are made. The Impact of Open Licensing on the Early Reader Ecosystem Table of contents List of tables .......................................................................................................................................... iii List of figures ......................................................................................................................................... iii Authors .................................................................................................................................................. iv Neil Butcher ....................................................................................................................................... iv Sarah Hoosen .................................................................................................................................... iv Lisbeth Levey .................................................................................................................................... -

Visually Impaired People)

Introduction State-of-the-Art What’s next Impact of ICT on the Teaching of Maths to VIP (Visually Impaired People) Dominique Archambault1, Dònal Fitzpatrick2 1Interfaces Non Visuelles et Accessibilité Département d’Informatique, UFR d’Ingénierie Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris 6 > > > http://chezdom.net/blog < < < 2School of Computing, Dublin City University > > > http://www.computing.dcu.ie/ dfitzpat < < < 5th JEM Workshop – Joining Educational Mathematics Institut Finlandais – Paris – 2008/11/27 Dominique Archambault, Dònal Fitzpatrick Teaching Maths to Visually Impaired People Introduction State-of-the-Art What’s next Motivation Learning @science Access to Maths as always been a problem to VIP Access to mathematics There is no reason that mathematical semantics can not be understood because of blindness. The biggest barrier is in fact access to mathematical content Where does lie the problem? Non visual representations Additional modalities used by the sighted Dominique Archambault, Dònal Fitzpatrick Teaching Maths to Visually Impaired People Introduction State-of-the-Art What’s next Motivation Learning @science Access to Maths as always been a problem to VIP Access to mathematics There is no reason that mathematical semantics can not be understood because of blindness. The biggest barrier is in fact access to mathematical content Where does lie the problem? Non visual representations • Speech =) Linear representations • Braille Additional modalities used by the sighted Dominique Archambault, Dònal Fitzpatrick Teaching Maths to Visually Impaired People Introduction State-of-the-Art What’s next Motivation Learning @science Access to Maths as always been a problem to VIP Access to mathematics There is no reason that mathematical semantics can not be understood because of blindness. -

Artwork Creation Guide Standardization for Digital Files

Artwork Creation Guide Standardization for Digital Files Artwork Creation Guide Standardization for Digital Files Disclaimer GlobalVision is a registered trademark of GlobalVision Inc. in Canada and/or other countries. All other company and product names are registered trademarks and/or trademarks of their respective owners. Artwork Creation Guide | Standardization for Digital Files This document contains information that is proprietary to the Artwork Creation Guide Group and the legal entity GlobalVision Inc. The work Artwork Creation Guide - Standardization for Digital Files is protected by copyright and/or other applicable laws. Any use of the work other than as authorized in writing or copyright law is prohibited. Contents I Preface ..................................................................................................................... 07 Section 1 Standardization ...................................................................................................... 09 1.1 Standardize on the operating system and its version ........................................ 11 1.2 Create a regular upgrade schedule for all software ........................................ 12 1.3 Standardize on office software ............................................................................ 13 1.4 Standardize on design software ........................................................................... 14 1.5 Centralize communication within the marketing department ........................ 15 Section 2 PDF Creation ...........................................................................................................