Proceedings of the Conference Universal Learning Design, Brno 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IADD BANA Braille Standards

Let Your Fingers Do The Talking: Braille on Folding Cartons in cooperation with February 2012 (Revision 1) 1 Preface 4 History of braille in folding carton production and references 2 Traditional Braille Cell and Braille Characters 5 Letters, punctuation marks, numbers, special characters 3 Standardization 7 Dot matrix, dot diameters, dot spacing, character and line spacing, embossing height, positioning the braille message 4 Technical Requirements 8 Functional and optical characteristics, material selection 5 Fabrication 9 Braille embossing, positioning of braille, amount of text 6 Prepress and Quality Assurance 12 Artwork files and print approvals, quality assurance 7 Conclusion 14 3 1 Preface In 1825, Frenchman Louis Braille (1809-1852) invented a reading system for the blind through which the alphabet, numbers and punctuation marks were represented in a tangible form via a series of raised dots. The braille system established itself internationally and is now in use in all languages. While A to Z is standardized, there are, of course, special characters which are unique to local languages. The requirement for braille on pharmaceutical packaging stems from the European Directive 2004/27/EC – amending Directive 2001/83/EC (community code to medicinal products for human use). This Directive includes changes to the label and package leaflet requirements for pharmaceuticals (which will not be discussed in this booklet). It requires pharmaceutical cartons to show the name of the medicinal products and, if need be, the strength in braille format. The influence of the European Directive is having an increasing impact on Canada, USA and other countries worldwide through the pharmaceutical packaging companies that produce for or market at an international level. -

The Braillemathcodes Repository

Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on "Digitization and E-Inclusion in Mathematics and Science 2021" DEIMS2021, February 18–19, 2021, Tokyo _________________________________________________________________________________________ The BrailleMathCodes Repository Paraskevi Riga1, Theodora Antonakopoulou1, David Kouvaras1, Serafim Lentas1, and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Speech and Accessibility Laboratory, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Math notation for the sighted is a global language, but this is not the case with braille math, as different codes are in use worldwide. In this work, we present the design and development of a math braille-codes' repository named BrailleMathCodes. It aims to constitute a knowledge base as well as a search engine for both students who need to find a specific symbol code and the editors who produce accessible STEM educational content or, in general, the learner of math braille notation. After compiling a set of mathematical braille codes used worldwide in a database, we assigned the corresponding Unicode representation, when applicable, matched each math braille code with its LaTeX equivalent, and forwarded with Presentation MathML. Every math symbol is accompanied with a characteristic example in MathML and Nemeth. The BrailleMathCodes repository was designed following the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Users or learners of any code, both sighted and blind, can search for a term and read how it is rendered in various codes. The repository was implemented as a dynamic e-commerce website using Joomla! and VirtueMart. 1 Introduction Braille constitutes a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired. -

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010 Developed as a Joint Project of the Braille Authority of North America and the Canadian Braille Authority L'Autorité Canadienne du Braille Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2011 by The Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be downloaded and printed, but not altered or sold. The mission and purpose of the Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats; the ease of production by various methods; and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii Canadian Braille Authority (CBA) Members CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) Canadian Council of the Blind Braille Authority of North America (BANA) Members American Council of the Blind, Inc. (ACB) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) American Printing House for the Blind (APH) Associated Services for the Blind (ASB) Association for Education & Rehabilitation of the Blind & Visually Impaired (AER) Braille Institute of America (BIA) California Transcribers & Educators for the Blind and Visually Impaired (CTEBVI) CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) The Clovernook Center for the Blind (CCBVI) National Braille Association, Inc. -

Braille in Mathematics Education

Masters Thesis Information Sciences Radboud University Nijmegen Braille in Mathematics Education Marc Bitter April 4, 2013 Supervisors IK183 Prof.Dr.Ir. Theo van der Weide Dr. Henny van der Meijden Abstract This research project aimed to make improvements to the way blind learners in the Netherlands use mathematics in an educational context. As part of this research, con- textual research in the field of cognition, braille, education, and mathematics was con- ducted. In order to compare representations of mathematics in braille, various braille codes were compared according to set criteria. Finally, four Dutch mathematics curricula were compared in terms of cognitive complexity of the mathematical formulas required for the respective curriculum. For this research, two main research methods were used. A literature study was conducted for contextual information regarding cognitive aspects, historic information on braille, and the education system in the Netherlands. Interviews with experts in the field of mathematics education and braille were held to relate the contextual findings to practical issues, and to understand why certain decisions were made in the past. The main finding in terms of cognitive aspects, involves the limitation of tactile and auditory senses and the impact these limitations have on textual aspects of mathematics. Besides graphical content, the representation of mathematical formulas was found to be extremely difficult for blind learners. There are two main ways to express mathematics in braille: using a dedicated braille code containing braille-specific symbols, or using a linear translation of a pseudo-code into braille. Pseudo-codes allow for reading and producing by sighted users as well as blind users, and are the main approach for providing braille material to blind learners in the Netherlands. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Multilingual the Hague: Municipal Language Policy, Politics, and Practice

Multilingual The Hague: Municipal language policy, politics, and practice Anne-Mieke M. M. Thieme Leiden University January 2020 Supervisor: Prof. I. M. Tieken-Boon van Ostade Second reader: Dr. D. Smakman Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been what it is today without the help of many people. First of all, I would like to express my greatest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. Her helpful feedback, enthusiasm, and insights encouraged me to get the most out of my Research Master’s thesis project. I am extremely thankful that she was my thesis supervisor. I would also really like to thank Dr Eduardo Alves Vieira for discussing my thesis ideas with me and giving useful advice about which directions I could consider. I am also grateful to the audience at Anéla’s 2019 Study Day about Multilingualism in Education and Society for their interesting comments. I am incredibly indebted to Peter Sips, Lodewijk van Noort, and Frank Welling of the municipality of The Hague, who kindly talked to me and gave me insight into municipal language policy. Without their help, this thesis would have an empty shadow in comparison to what it is now. They showed me how relevant the topic was, inspiring me to dig deeper and push further. Thank you so much, Peter, Lodewijk, and Frank. Lastly, I would like to thank my family and friends for the unconditional support they gave me, for listening to my ideas, and asking helpful questions. I am forever grateful that they were there for me along the way. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

Hanke, Peter, Ed. International Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 258 389 EC 172 909 AUTHOR Cylke, Frank Kurt, Ed.; Hanke, Peter, Ed. TITLE International Directory of Libraries and Production Facilities for the Blind. INSTITUTION International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, London (England).; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. SPONs _3ENCY United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Paris (France). PUB DATE 84 CONTRACT UNESCO-340029 NOTE 109p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE mF01/PCOS Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Blindness; *Braille; International Programs; Physical Disabilities; Reading Materials; Sensory Aids; *Special Libraries; *Talking Books ABSTRACT World-wide in scope, this directory lists organizations producing braille or Talking Books, maintaining braille libraries, and exchanging resources with organizations serving blind or handicapped people. The directory is arranged in seven geographical sections: Africa, Asia, Australia (including Oceania), Europe (including U.S.S.R.), Middle East (northern Africa and the eastern Mediterranean countries), North' America, and South America (including Central America and the Caribbean). Countries are arranged- alphabetically within these seven sections and individual organizations alphabetically within their countries. Information about each organization includes five parts: braille production, braille distribution, Talking Books production, Talking Books distribution, and general information. -

A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Effectiveness of Educational Interventions to Support Children and Young People with Vision Impairment

SOCIAL RESEARCH NUMBER: 39/2019 PUBLICATION DATE: 12/09/2019 A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Digital ISBN 978-1-83933-152-7 A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment Author(s): Graeme Douglas, Mike McLinden, Liz Ellis, Rachel Hewett, Liz Hodges, Emmanouela Terlektsi, Angela Wootten, Jean Ware* Lora Williams* University of Birmingham and Bangor University* Full Research Report: < Douglas, G. et al (2019). A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of educational interventions to support children and young people with vision impairment. Cardiff: Welsh Government, GSR report number 39/2019.> Available at: https://gov.wales/rapid-evidence-assessment-effectiveness- educational-interventions-support-children-and-young-people-visual-impairment Views expressed in this report are those of the researcher and not necessarily those of the Welsh Government For further information please contact: David Roberts Social Research and Information Division Welsh Government Sarn Mynach Llandudno Junction LL31 9RZ 0300 062 5485 [email protected] Table of contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 5 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................... -

Analysis of Teachers' Perceptions on Instruction of Braille Literacyin

ANALYSIS OF TEACHERS’ PERCEPTIONS ON INSTRUCTION OF BRAILLE LITERACYIN PRIMARY SCHOOLS FOR LEARNERS WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN KENYA CHOMBA M. WA MUNYI E83/27305/2014 A RESEARCHTHESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION KENYATTA UNIVERSITY JUNE, 2017 ii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Chomba M. WaMunyi E83/27305/2014 Supervisors: This dissertation has been submitted for appraisal with our/my approval as University supervisor(s). Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Dr. Margaret Murugami Department of Special Needs Education, Kenyatta University Signature _________________________ Date ______________________ Dr. Stephen Nzoka Department of Special Needs Education, Kenyatta University Signature ________________________ Date ______________________ Prof. Desmond Ozoji Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of JOS iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to all children with visual impairment in Kenya. iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ....................................................................................................... -

Perpustakaan Braille Di Kota Semarang

PERPUSTAKAAN BRAILLE DI KOTA SEMARANG TUGAS AKHIR UNTUK MEMPEROLEH GELAR SARJANA ARSITEKTUR Oleh Sadhu Adwitya Adhiwiajna 5112411017 PRODI ARSITEKTUR FAKULTAS TEKNIK SIPIL UNIVERSITAS NEGERI SEMARANG 2015 TUGAS AKHIR ustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang ii TUGAS AKHIR Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang hapsoro adi iii TUGAS AKHIR ustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang iv TUGAS AKHIR Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang hapsoro adi KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur kami panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT yang telah memberikan rahmat, taufik dan hidayah-Nya sehingga penyusun dapat menyelesaikan Landasan Program Perencanaan dan Perancangan Arsitektur (LP3A) Tugas Akhir Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang ini dengan baik dan lancar tanpa terjadi suatu halangan apapun yang mungkin dapat mengganggu proses penyusunan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini. LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini disusun sebagai salah satu syarat untuk kelulusan akademik di Universitas Negeri Semarang serta landasan dasar untuk merencanakan desain Perpustakaan Braille nantinya. Judul Tugas Akhir yang penulis pilih adalah ” Perpustakaan Braille di Kota Semarang”. Dalam penulisan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini tidak lupa penulis untuk mengucapkan terimakasih kepada semua pihak yang telah membantu, membimbing serta mengarahkan sehingga penulisan LP3A Perpustakaan Braille ini dapat terselesaikan dengan baik. Ucapan terimakasih saya tujukan kepada : 1. Allah SWT, yang telah memberikan kemudahan, kelancaran, serta kekekuatan sehingga dapat menyelesaikannya dengan baik 2. Bapak Prof. Dr. Fathur Rohman, M.Hum., Rektor Universitas Negeri Semarang 3. Bapak Dr. Nur Qudus, M.T., Dekan Fakultas Teknik Universitas Negeri Semarang 4. Bapak Drs. Sucipto, M.T., selaku Ketua Jurusan Teknik Sipil Universitas Negeri Semarang 5. Bapak Ir. Bambang Bambang Setyohadi K.P, M.T., selaku Kepala Program Studi Teknik Arsitektur S1 Universitas Negeri Semarang yang memberikan masukan, arahan dan ide-ide nya selama di perkuliahan 6. -

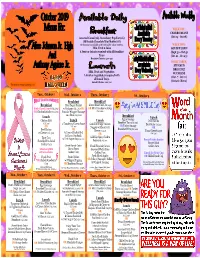

October 2019 Menus For

October 2019 WEEK ONE: CHARRO BEANS Menus For: (Oct 14 - Oct 18) Assorted Cereal (1G), Strawberry Pop Tart(1G) OR Double Chocolate Mini Muffin (1G) Grahams are available with each of the above entrées. WEEK TWO: Milk, Fruit & Juice GOLDEN CORN Alice Johnson Jr. High A Fruit or Juice is required with all Breakfast (Sept 30 - Oct 4) Trays (Oct 21 - Oct 25) Breakfast Calories: 400-550 And WEEK THREE: STEAMED Anthony Aguirre Jr. BROCCOLI Milk, Fruit and Vegetables. W/CHEESE A Fruit or Vegetable is required with (Oct. 7 - Oct 11) all Lunch Trays. Lunch Calories: 600-700 (Oct 28 - Nov 1) This institution is an equal opportunity provider. Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Fruit Yogurt Parfait Glazed Sweet Roll (Cal./230) Pink Glazed Donut (Cal./289) w/Grahams (Cal./281) OR OR Mini Pancakes w/Syrup OR Chicken Kolache (Cal./180) (Cal./260) Pancake Wrapped Sausage on a Stick (Cal./210) Breakfast Lunch Egg & Sausage Lunch Chicken Melt Lunch Lunch Pork Carnita (Cal./331) 2 Tamales w/Cheese Sauce Gold Kist Crispy Chicken Breakfast Taco (Cal./296) OR Turkey Sausage Enchiladas (Cal./409) OR (Cal./390) Nuggets w/Macaroni & OR OR Breakfast Pizza (Cal./210) Beef Nachos Cheese (Cal./428) Texas Cheeseburger w/Cheese (Cal./328) ½ Toasted Turkey Deli OR (Cal./385) & Cheese Sandwich Gold Kist Spicy Chicken Tater Tots w/Trix Yogurt Cup (Cal./251) Sandwich (Cal./376) Emoji Potato Smiles Shredded Pico Salad Golden Corn Burger Salad Sweet Carrot Coins Fresh Flavored Carrots Golden Corn Strawberry Milk Charro Beans Seasoned Waffle Fries will be available. Golden Corn