Reflections on Moravian Pietism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of Moravian Missionary Photography in Labrador Hans Rollmann

The Beginnings of Moravian Missionary Photography in Labrador Hans Rollmann he Uni ty Archives of T the Moravian Church at Herrnhut, Saxony, include a collec tion of mor e than 1,000 photo graphic plates taken by missionar ies in Labrador, besid es a smaller co ll ec tio n that comes from Greenland. These historic photo graphs, takenbetween the late 1870s and the early 1930s, cover themati cally a wide range of missionary, aboriginal, and settler existence on Labrador's north coast, from loca tions and settlements to Inuit life and labor. The photographs complement earlier artistic and ar chitectural depictions of the Labra dor settlements that were made to record the Moravian presen ce in Labrador. Unlike the earlier art, the photographs reached an increas ingly wider public in print through major German and English peri odicals, notably Missions-Blatt, Pe riodical Accounts,and MoravianMis sions. In addition, these phot o Walter Perrett photographing Inuit w omen from Labrador on a bundle offish. graphs were used sys tema tically in Photograph by Paul Hettasch; early twentieth century. Courtesy of the Unity print and slide pr esentations de Archives, Herrnhut, Germany. signed to maintain the link between the mission field and the home congregations and raise aware found there were ethnically related to the Inuit of Greenland, ness and funds in church circles for the Labrador Mission. whom the Moravians had begun evangelizing in 1733. With the This essay does not aim to interpret the content, aim, or approval and support of the British government, Moravian artistic merit of the photographic representations by Labrador missionaries settled perman ently in northern Labrad or begin missionaries. -

Erläuterungen Zur Geologischen Specialkarte Des Königreichs

Erläuterungen i'ur geologischen Specialkarte des Königreichs Sachsen. Herausgegeben vom K. Finanz -Ministerium. Bearbeitet unter der Leitung Hermann Credner. Scction Löbau-Hcrrnhut Blatt 7'J ToD Th. Siegert. Leipzig, in Commission bei W. Engclmann. 1894. Preis der Karte nobat Erläuterungen 3 Mark. SECTION LÖBAU-HERRNH UT. Oberflächengestaltung. Das Gebict der Section Löbau- Herrnhut bildet einen Theil des Lausitzer Hügellandes. Seine schwach wellige bis hügelige Oberfläche besitzt durchschnittlich 300 m Meereshöhe und nur wenige Gipfel überragen das Niveau von 400 m; so erreicht der Kottmar mit seinem höchsten, nur wenig westlich von der Sectionsgrenze gelegenen Scheitel 583 m, der Löbauer Berg 449,9 m, der Wolfsberg zwischen Oberherwigs dorf und Strahwalde 445,6 m, der rothe Berg südöstlich vom Kottmar 436,2 m, der Hirschberg nördlich vom Wolfsberg 429,7 m, der Holzel-, der Lehmanns- und der Lehn-Berg bei Strahwalde 426,7 m, 418,4 m und 411 m, endlich der Lerchenberg 401,7 m. Der tiefste Punkt der Section liegt am Ostrande des Blattes im Pliesnitz-Thale bei Bernstadt in 225 m Meereshöhe. Die Granitberge bilden durchgängig flache, breite Rücken; einige der basaltischen Erhebungen, wie der Spitzberg bei Ober- sohland, der Hutberg bei Herrnhut und der Hirschberg bei Ober herwigsdorf, zeigen eine schöne kuppenförmige Gestalt, während der über seine flache Umgebung stark dominirende, aus Basalt und Dolerit zusammengesetzte Löbauer Berg sich in zwei Gipfel gliedert und der massige, zu oberst aus Basalt und Phonolith bestehende Kottmar die Form eines Tafelberges besitzt. Der Löbauer Berg trägt auf seinem westlichen Gipfel den eisernen Friedrich- August- Aussich tsthurm, auf seiner etwas höheren und durch eine flache Einsenkung abgetrennten östlichen Partie, dem Schafberge, einen Stein wall, dessen Nordwestseite am besten erhalten ist und der z. -

Stadt Herrnhut

Herrnhut Small Town, Global Importance Welcome to Herrnhut! Herrnhut, our »small town of global impor - tance«, holds many stories. Let us invite you on a journey through the following pages to tell you some of them. Whether Herrnhut Stars, baroque architecture, companies rich in tradition or religious life you will see that our stories did not end a long time ago – they can still be seen and felt today and 1 will forever form the foundation for future developments. Culture and religious observance, crafts and entrepreneurship, being in touch with nature and recreation: all these things come together in Herrnhut to create its unique character. I hope you will enjoy your discoveries! Willem Riecke Mayor of Herrnhut 2 1 »Maternal Happiness« (»Mutterglück«) – sculpture in the Herrschaftsgarten 2 View towards the Church from Augus t- Bebe l- Straße 3 View of Comeniusstraße 4 Church Cupola 5 Burial Ground / Go d’s Acre (Gottesacker) 6 Christmas Eve in Herrnhut 7 The Hills around Herrnhut 1 HERRNHUT 3 Small Town, Global IMPORTANCE Herrnhut is situated in the heart of the scenic of the place where Germany, Poland and the Upper Lusatia. Together with the surrounding Czech Republic meet. Within this border area, you villages Berthelsdorf, Großhennersdorf, Ruppers - will be tempted by many destinations along the dorf and Strahwalde the number of inhabitants »Via Sacra«, by nearby mountains and lively towns, 4 totals almost 6,300 people. such as Liberec in the Czech Republic and Görlitz, It is true that Herrnhut is a small town, but as its which spans the river Neisse. history and present are closely connected with the worldwide Moravian Church Herrnhut is brim - You are most welcome to Herrnhut in Upper ming with an international atmosphere. -

Kurt Aland in Memoriam

KURT ALAND IN MEMORIAM KURT ALAND IN MEMORIAM 0 1995 by Hemiann KurstStifhlng zur POdenmg der neuteslameniüchenTextfnaehmg M143Münrier/W., Geo~gskornmende7 HersieUunp: Re-g Münster INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Universitätsprediger Prof. Dr. Friedemann Merke1 Predigt im Trauergottesdienst für Prof. D. Kurt Aland am 21. April 1994 .......................................................................................... 7 Grußworte und Reden anläßlich der Gedenkakademie für Prof. D. Kurt Aland am 31. März 1995 im Festsaal des Rathauses zu Münster: Präses D. Hans-Martin Linnemann, stellv. Vorsitzender des Kuratoriums der Hermann Kunst-Stiftung zur Förderung der neutestamentlichen Textforschung Grußwort................................................................................................. 12 Prof. Dr. Erdmann Sturm, Dekan der Evangelisch-Theologi- schen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster Grußwort.............................................................................................. 14 Prof. Dr. Martin Hengel Laudatio Kurt Aland ............................................................................. 17 Landesbischof i.R. Prof. D. Eduard Lohse, Vorsitzender des Vorstands der Hermann Kunst-Stiftung zur Förderung der neutestamentlichen Textforschung Wahrheit des Evangeliums - Zum Gedenken an Kurt Aland .... 35 Bibliographie Kurt Aland (zusammengestellt von Beate Köster und Christian Uhlig t)..... 41 Die wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiter Kurt Alands seit 1959............ 72 Friedemann Merke1 PREDIGT IM TRAUERGOTTESDIENST'FÜR -

Schadstoffmobil 2021 (PDF)

EINSATZ SCHADSTOFFMOBIL 2021 Angenommen werden solche Problemstoffe aus Haushalten der Bevölkerung, wie Farben, Lacke, Lösungsmit- tel, Batterien, Kondensatoren, Altmedikamente, Leuchtstoffröhren, Energiesparlampen, Pflanzenschutzmittel, Schädlingsbekämpfungsmittel, Desinfektionsmittel, Holzschutzmittel, Chemikalien, Laugen, Säuren, Salze und Fotochemikalien. Nicht angenommen werden: Altreifen, Lkw-Akkumulatoren, Druckgasflaschen, infektiöse Abfälle, Kühlschrän- ke, Munition, Sprengstoff, Zement, Zementasbestplatten, Dachpappe und andere Bauabfälle. Gemäß Abfallwirtschaftssatzung des Landkreises Görlitz werden Problemstoffe in haushaltsüblichen Mengen bis maximal 20 l bzw. 20 kg pro Jahr je Abfallbesitzer oder Abfallerzeuger, bezogen auf Restabfallbehälter und Jahr am Schadstoffmobil angenommen. Die Abgabe der Problemstoffe kann nur beim Personal am Fahrzeug erfolgen. Flüssigkeiten werden in dicht verschlossenen Behältnissen angenommen. Problemstoffe möglichst immer in Originalverpackungen abgeben, da auf den Verpackungen Hinweise zur Zusammensetzung und zum Umgang enthalten sind. Für Altöle gilt die Altölverordnung; für gebrauchte Batterien und Akkumulatoren die Batterieverordnung. Schrott, sperrige Abfälle oder Haushaltgeräte werden am Schadstoffmobil nicht angenommen. I. Quartal II. Quartal III. Quartal IV. Quartal Stellplatz 2021 2021 2021 2021 Mittelherwigsdorf / OT Radgendorf 18.01.2021 26.04.2021 26.07.2021 25.10.2021 Parkplatz Mehrzweckgebäude 14.00 - 14.45 Uhr 16.30 - 17.00 Uhr 10.00 - 10.30 Uhr 14.00 - 14.45 Uhr Zittau - West -

175 Jahre Zuverlässig Winterdruck

Verlag + Anzeigenverwaltung: WinterDruck · % 03 58 73-41 80 Vertrieb + Abonnement: Mongolei-Laden Hannelore Klätte Amtsblatt für Herrnhut mit Ruppersdorf, Berthelsdorf mit 23·2008 Herrnhut, August-Bebel-Straße 12 · % 03 5873-4 01 66 Rennersdorf; Großhennersdorf, Strahwalde, die Verwaltungs- Verantwortlich für die amtlichen Nachrichten: 4. Dezember / –,45 € die Bürgermeister der Orte oder ihre Beauftragten. gemeinschaft u.d.Abwasserzweckverband »Oberes Pließnitztal« 175 Jahre zuverlässig WinterDruck Mitarbeiter von WinterDruck vor dem ehemaligen Druckereigebäude auf dem Stolpener Markt Seite 2 Kontakt 23-08 VERANSTALTUNGSKALENDER Sonnabend 6.12.2008 Ruppersdorf 13.30 Uhr Rentnertreff Ruppersdorf: Weihnachtsfeier in der Turnhalle Ruppersdorf Herrnhut 14.30 Uhr Seniorenverein Herrnhut: Weihnachtsfeier für alle Senioren der Stadt Herrnhut im FFw-Heim Herrnhut Sonntag 7.12.2008 Herrnhut 15.00 Uhr Brüdergemeine: Gemeinde-Adventsfeier im Saal der Brüdergemeine Großhennersdorf Seniorenverein e.V. Neundorf auf dem Eigen: Adventsnachmittag im Weißbachtal Berthelsdorf 17.00 Uhr Verein Freunde des Zinzendorfschlosses: Adventskonzert – Benefizkonzert – in der Kirche (siehe Seite 7) Dienstag 9.12.2008 Strahwalde 14.00 Uhr »Heimatbund Deutscher Vertriebener Löbau e.V.«: Weihnachtsfeier in der Gaststätte »Grüner Baum« Mittwoch 10.12.2008 Herrnhut 13.30 Uhr Seniorenverein Herrnhut: Lichtelfahrt mit Überraschungen ab den bekannten Haltestellen Strahwalde 14.00 Uhr Seniorenclub Strahwalde: Weihnachtsfeier im Volkshaus (siehe Seite 26) Herrnhut 17.00 Uhr Adventssingstunde mit dem Krippenspiel des Kinder- gartens im Saal der Brüdergemeine Donnerstag 11.12.2008 Großhennersdorf 15.00 Uhr Seniorensportgruppe Großhennersdorf: Weihnachtsfeier Herrnhut 20.00 Uhr Brüdergemeine: Tanzkreis in der »Arche« Sonnabend 13.12.2008 Berthelsdorf 10–15 Uhr Vorweihnachtlicher Basar im »Häus’l« (s. Seite 9) Rennersdorf 14.00 Uhr Seniorenverein Rennersdorf e.V.: Weihnachtsfeier in Dittersbach im Kultur- und Sportzentrum (s. -

A History of Religious Educators Elmer L

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Books The orkW s of Elmer Towns 1975 A History of Religious Educators Elmer L. Towns Liberty University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/towns_books Recommended Citation Towns, Elmer L., "A History of Religious Educators" (1975). Books. Paper 24. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/towns_books/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The orkW s of Elmer Towns at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contents Contributors Preface Part One A.D. 1-500 1 Jesus / Donald Guthrie 2 Paul / Richard N. Longenecker 3 Augustine / Howard Grimes Part Two A.D. 500-1500 4 Columba / John Woodbridge 5 Thomas Aquinas / Joan Ellen Duval 6 Geert Groote / Julia S. Henkel Part Three A.D. 1500-1750 7 Erasmus / Robert Ulich 8 Martin Luther / Harold J. Grimm 9 Huldreich Zwingli / H. Wayne Pipkin 10 Ignatius of Loyola / George E. Ganss 11 Philip Melanchthon / Carl S. Meyer 12 John Knox / Marshall Coleman Dendy 13 John Calvin / Elmer L. Towns 14 John Amos Comenius / W. Warren Filkin, Jr. 15 August Hermann Francke / Kenneth 0. Gangel 16 Nikolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf / T. F. Kinloch Part Four A.D. 1750-1900 17 John Wesley / Elmer L. Towns 18 Robert Raikes / Elmer L. Towns 19 Johann H. Pestalozzi / Gerald Lee Gutek 20 Johann Friedrich Herbart / Abraham Friesen 21 Thomas Arnold / William R. Feyerharm 22 John Henry Newman / Bernard Ramm 23 Horace Bushnell / Elmer L. -

History of Modern Missions

Section Two: The Beginning of the Modern Missionary Movement Lesson Three: The Moravians Introduction: - Count Zinzendorf and Herrnhut 1. Revival at Herrnhut • July 16, 1727 Prayer at Herrnhut • August 13, 1727 Moravian Pentecost 2. Missionary Movement from Herrnhut • 1732 First Missionaries go to West Indies • 1733 – 1737 Missions begin in Greenland, South America, North America, and South Africa. • 1752 Mission to Labrador 3. The Moravians influence upon John Wesley • Wesley initial encounter with Moravians. • Peter Bohler – Wesley's conversi on Count Zinzendorf (1700-1760) Count Nicholas Ludwig Zinzendorff was born in Dresden and brought up as a Lutheran Pietist. Religion had become for many in his day mere intellectual assent for particular doctrines. Zinzendorff preached the need for a personal relationship with Christ. When approached by Christian David, he allowed the Moravians who wanted to stay on his land, he gave his permission (1722). They called the place Herrnhut (The Lord's Watch). Count Zinzendorf He wanted only to know Jesus in closer relationship. He summed up his life in these words "I have one passion, tis Jesus, Jesus only" Zinzendorf was greatly moved when he saw a painting of Jesus by Domenico Feti. The painting was displayed at the Dusseldorf Art Gallery. At the bottom of the painting are the words written in Latin: "This have I done for you; What have you done for Me?" Christian David (1690 – 1751) 1690 Born December 31st in Senftleben, Moravia. Brought up a Roman Catholic. 1710 Protestants preached salvation by faith in Christ alone Sought for truth - Read through the Bible; Sought instruction from Jews Eventually left Catholic Moravia and joined Lutherans in Berlin. -

Februar 2019

NIESKYER NACHRICHTTENE Amtliches Bekanntmachungsblatt der Großen Kreisstadt Niesky 2 / 2019 Mittwoch, 13. Februar 2019 VERANSTALTUNGSHINWEISE Konrad-Wachsmann-Haus 23.2.2019 8.00 Uhr Treffpunkt: REPO Dauerausstellung Wanderung östlich der Neiße (PL), »Holzbauten der Moderne« von Radmeritz zum Witka-Stausee Entwicklung des industriellen (12 km) mit den Freien Wanderern Holzhausbaus aus Niesky bis Februar 2019 Sonderausstellung 25./26.2.2019 9.00 bis Konrad-Wachsmann-Haus »Maßstabgetreu – 11.00 Uhr »Mit dem Malblock Unsichtbares Architektur modelle entdecken …«, für Kinder ab 6 Jahre im Konrad-Wachsmann-Haus« 27.2.2019 14.00 bis Konrad-Wachsmann-Haus bis Februar 2019 Rathaus 15.00 Uhr »Geschichten für starke Kinder« Fotoausstellung »Holzgerlingen erzählt von Marion Kristina Vetter heute – Bilder unserer Stadt« foto- 2.3.2019 20.00 Uhr Bürgerhaus grafiert von Roland Fuhr und Jürgen Faschingsveranstaltung des KCN, Schülke vom Photoclub Blende 96 das Motto lautet: »Geschichten übern aus der Partnerstadt Holzgerlingen Gartenzaun – der KCN geht Äppel klaun« bis 10.3.2019 Johann-Raschke-Haus 4.3.2019 16.00 Uhr Bürgerhaus Sonderausstellung Seniorenfasching »Häuser und Gesichter – Spaziergänge durch die Nieskyer 8.3.2019 19.30 Uhr Bürgerhaus Vororte Neuhof, Neuödernitz Zum Frauentag und Neusärichen« die Dresdner Salon-Damen »Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß …« 16.2.2019 16.00 Uhr Bürgerhaus 9.3.2019 19.30 Uhr Bürgerhaus Heimatgefühle – Sigrid & Marina, Elternball der Grundschule und zu Gast sind die Wildecker Herz buben, Oberschule Niesky sowie des Vencent -

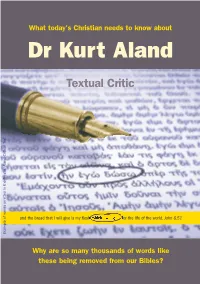

The Doctrinal Views of Dr Kurt Aland, Textual Critic

A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 1 What today's Christian needs to know about Dr Kurt Aland Textual Critic and the bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world. John 6.51 Example of words omitted in the Nestle/Aland Critical Text Why are so many thousands of words like these being removed from our Bibles? A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 3 What today's Christian needs to know about DR KURT ALAND Textual Critic A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 4 Product Code: A122 ISBN 978 1 86228 344 2 © 2007 Trinitarian Bible Society Tyndale House, Dorset Road, London, SW19 3NN, UK 5M/12/07 A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 1 What today's Christian needs to know about DR KURT ALAND Textual Critic by A. Hembd, MACS Reformation International Theological Seminary A consultant to the Society r Kurt Aland is perhaps the Received Text which was used by all most renowned Biblical the great translations of the textual critic of the Reformation, including the Authorised 20th century. Born in Version in the English language (also DBerlin in 1915, he died in Münster/ known in some parts of the world as Westphalia in 1994. The most famous the ‘King James Version’). Thus, the modern English versions of the New versions translated from this new Testament—the Revised Standard ‘critical’ text differ significantly from Version, the New American Standard our Authorised Version as well. -

The Text of the New Testamentl

Grace Theological lournal9.2 (1988) 279- 285 REVIEW ARTICLE The Text of the New Testament l DANIEL B. WALLACE The Text of the New Testament, by Kurt and Barbara Aland. Translated by Erroll F. Rhodes. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans/Leiden: E. 1. Brill, 1987. Pp. xviii + 338. $29.95. Cloth. With the long-awaited translation of Der Text des Neuen Testaments (1982), English-speaking students may now share in the debt of gratitude owed to the well-known German scholars, Kurt and Barbara Aland. The five-year delay, due to a number of complications, has resulted in more than a translation; the English edition "represents a revision of the original Ger man edition of 1982" (translator's preface, viii). Though modeled after Wtirthwein's Der Text des Alten Testaments (ET: The Text of the Old Testament [1979]), the NT counterpart tends to be more practical since a follow-up volume by Kurt Aland for advanced students is in the present time (Uberliejerung und Text des Neuen Testaments: Handbuch der modernen Textkritik). Nevertheless, the advanced student and scholar alike can profit from this volume: the computer-generated/ assisted tables, charts, and collations are, by themselves, worth the price of the book, representing the equivalent of countless thousands of man-hours. This could only have been produced at the Institute for New Testament Textual Re search in Munster. Besides sixty-five plates (all but three of various NT manuscripts), eight tables and six charts (including one two-sided detached fold-out), the Alands have provided the essentials for a thorough introduction to textual criticism: an overview of the history of the printed NT text-from Erasmus to Nestle Aland26 (=UBSGNT3); a discussion of the interrelation of early church history and NT textual criticism (our appetites are barely whet, however, in the twenty-four pages on this topic); a description of the extant Greek manuscripts, as well as Greek patristic evidence (it should be noted here that readers of Metzger's Text of the New Testament2 will find this chapter to be II wish to thank Dr. -

The Planning and Development of Two Moravian Congregation Towns: Salem, North Carolina and Gracehill, Northern Ireland

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The Planning and Development of Two Moravian Congregation Towns: Salem, North Carolina and Gracehill, Northern Ireland Christopher E. Hendricks College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, United States History Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Hendricks, Christopher E., "The Planning and Development of Two Moravian Congregation Towns: Salem, North Carolina and Gracehill, Northern Ireland" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625413. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-85yq-tg62 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF TWO MORAVIAN CONGREGATION TOWNS SALEM, NORTH CAROLINA AND GRACEHILL, NORTHERN IRELAND A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christopher Edwin Hendricks 1987 ProQuest Number: 10627924 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.