And the Transformation of the Dumbarton Oaks Gardens Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the City of Brooklyn and Kings County Volume II, by Stephen M

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the City of Brooklyn and Kings County Volume II, by Stephen M. Ostrander This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A History of the City of Brooklyn and Kings County Volume II Author: Stephen M. Ostrander Editor: Alexander Black Release Date: May 14, 2013 [EBook #42712] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF BROOKLYN, KINGS CNTY, VOL 2 *** Produced by Charlene Taylor, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) Transcriber's Notes Volume I of this eBook is available at Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41979, eText # 41979. On some devices, clicking on a blue-bordered image will display a larger version of it. VILLAGE OF BROOKLYN IN 1816 A HISTORY OF THE CITY OF BROOKLYN AND KINGS COUNTY BY STEPHEN M. OSTRANDER, M.A. LATE MEMBER OF THE HOLLAND SOCIETY, THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, AND THE SOCIETY OF OLD BROOKLYNITES EDITED, WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES, BY ALEXANDER BLACK AUTHOR OF "THE STORY OF OHIO," ETC. IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II. BROOKLYN Published by Subscription 1894 Copyright, 1894, BY ANNIE A. OSTRANDER. All rights reserved. This Edition is limited to Five Hundred Copies, of which this is No. -

January 1976

A~~OOO@£~ R ~ w~ rl!n!ll ~ oo Journal of the American Revenue Association Vol. 30, No. 1, Whole Number 281 January 1976 The Dies of the U. S. Private Die Proprietary Medicine Stamps Part I By Associate Editor Richard F. Riley ABSTRACT The more interesting private die proprietary medicine stamps are exam ined, evidently for the first time, for evidence of the utilization of the various engraving techniques available to the artisans of the period. The analysis, while speculative to a considerable degree may prove of interest to the col lector of any of the early U. S. revenues, private die or otherwise. It is found that the private die proprietaries form an exemplary subject for such an analysis, possibly the best philatelic example available. This is becausl'. several denominations of stamps were used by more than one company, th~ latter occasioning name changes on the issued stamps. From the analysi,;; which will follow in installments, a new die variety or two emerges, consider able appreciation of the artistry of our early steel engravers is acquired an•! finally, several chapters later, an enigma or two is uncovered for the delecta-· tion of others to follow. INTRODUCTION Collectors of U. S. private die proprietary stamps are aware that in gen eral, companies which employed two or more denominations of stamps haci. emissions which looked alike except for tablets showing the denominations. In instances where there was a change in corporate name the emissions of the successor differed principally in the name inscribed on the stamp. A com plete listing of the latter parent-offspring relationships was provided by Louis Alfano in The American Revenuer, under the title: "Die Alterations of Private Die Proprietary Stamps"! Another look-alike aspect which collectors may have noticed is that the private die stamps commonly show an interesting degree of symmetry top to bottom and left to right, and that a number have familiar design features possibly borrowed from the then current postal issues. -

Seduced Copies of Measured Drawings Written

m Mo. DC-671 .-£• lshlH^d)lj 1 •——h,— • ULU-S-S( f^nO District of Columbia arj^j r£Ti .T5- SEDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Building Survey National Park Service Department of the Interior" Washington, D.C 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DUMBARTON OAKS PARK HABS No. DC-571 Location: 32nd and R Sts., NW, Washington, District of Columbia. The estate is on the high ridge that forms the northern edge of Georgetown. Dumbarton Oaks Park, which was separated from the formal gardens when it was given to the National Park Service, consists of 27.04 acres designed as the "naturalistic" component of a total composition which included the mansion and the formal gardens. The park is located north of and below the mansion and the terraced formal gardens and focuses on a stream valley sometimes called "The Branch" (i.e., of Rock Creek) nearly 100' below the mansion. North of the stream the park rises again in a northerly and westerly direction toward the U.S. Naval Observatory. The primary access to the park is from R Street between the Dumbarton Oaks estate and Montrose Park along a small lane presently called Lovers' Lane. Present Owner; Dumbarton Oaks Park is a Federal park, owned and maintained by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. Dates of Construction: Dumbarton Oaks estate was acquired by Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss in 1920. At their request, Beatrix Jones Farrand, a well- known American landscape architect, agreed to undertake the design and oversee the maintenance of the grounds. -

Clothing Store, :'.I Perhaps Beneath Pacific's Skies

UBLISHED EVERY TUESDAY MORNING BY A. H.BYINGTON & CO.,': AT TWO DOLLARS PER ANNUM, IN ADVANCE r JV Jamilfi §mki to §ml Urns nnd Interests, d»jenev»l gttMUjieiwe, ptewtow, gJolitUs, J^rintltaw, ISgedtauus, &t.—^stflMislied in 1800. NUMBER 1010--NEW SERIES, NORWALK, CONN.. TUESDAY, MAY 21,1807. VOLUME L—NUMBER.21. 1.: Go to Hall & Bead 's, Bridgeport, for Carpets and Pa per Hangings. Up in the Barn. , j Bible Society of Norwalk and A Minister Wanted. Seff. Davis' Disguise. Old Firmer Joe steps through the doors, It has been doubted that Jeff Davis was Its Vicinity. A work has just been published by the NORWALK As wide to him as gates of/Thebes; SEVENTH ANNDAL REPORT. PRESENTED American Tract Society entitled, "Hints and actually captured in female attire, and his "TORWALK GAZETTE. REAL ESTATE. Bounties, Pensions, die. sympathizers labored strenuously to dis TTAVING just discovered that there has been i •And lltoiigliilul walksabouljtlu! floors r;r„-n IN THE BAPTIST CHTJBCQ, NORWALK, Thoughts for Christians," written by Rev. prove the s'ories which presented him in J1 report widely circulated that I have given ni Wlicrt on are piled lii°9 winter stores, , n APRIL 14TH, 1867. • - Dr. Todd, of Pittsfleld, -who has a way of The Second Oldest Paper in the Slate. INSURANCE COMPANY. the United States Claim Agency business, wbicl i 1 • 1 tf£ putting things" which cannot be excelled.— such a ludicrous aspect before the world. Homestead for Sale. has been believed by some. I would here state to Aud couuts the profits of hi.1 glebes. -

July 01,1868

---. ESS. E.u,ut.hea June 23,1862. Voi. 7. WEDNESDAY JULY PORTLAND,7 MORNING, 1, 1868. „ _’ _±ermsVw*y vs.uu per annum, in advance. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS is published BUSINESS CARDS. board akd rooms. every day, at No. 1 Printers* MISCELLANEOUS. all their rights ol as (Sunday excepted.) citizenship though they wore instantly turn the Eteuange, Exchange Street. Portland. native born; ami no citizen of the United Siat. s, conversation to some othe native or naturaliz must be liable to arrest N. A. FOSTER, Peoprixi ob. CHAKLFS E. T. DAILY PRESS. d, and topic. SHAW, Boarders Wanted. imprisonment by any foreign power for acts done or [' Terms Dollars a m advance. We entered the :—Eight year oldest and well A GENT!.EM \N an! words six Ken in this and if th are so ar- hall (The only known) Dividend Paid in 1808—100 wile, or two gentlemen can PORI 'LAN D. country; y again, which extern s Single copies 4 cents eent. ^Abe accommodated with rested and it is the ol the being per board at 27 Wilmot St. imprisoned, duty govern- through the house from one BILL I Beterenccs ment to intertere in their behalf. side to the otl POSTER, exchanged. jnnt30dlw* THK MAINWS'l’Vi Q. ->uWi«he<l »t the er, and, out Corner Coneress and Market !Ms., Tenth—Of all who were faithful in the trials of going door, passed in at same place every Thur. at a another $2.00 vear, Wednesday 1868. the late war there were none entitled to more special in advance. -

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 2016–2017 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Annual Report 2016–2017 © 2017 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. ISSN 0197-9159 Cover photograph: The Byzantine Courtyard for the reopening of the museum in April 2017. Frontispiece: The Music Room after the installation of new LED lighting. www.doaks.org/about/annual-reports Contents From the Director 7 Director’s Office 13 Academic Programs 19 Fellowship Reports 35 Byzantine Studies 59 Garden and Landscape Studies 69 Pre-Columbian Studies 85 Library 93 Publications 99 Museum 113 Gardens 121 Friends of Music 125 Facilities, Finance, Human Resources, and Information Technology 129 Administration and Staff 135 From the Director A Year of Collaboration Even just within the walls and fencing of our sixteen acres, too much has happened over the past year for a full accounting. Attempting to cover all twelve months would be hopeless. Instead, a couple of happenings in May exemplify the trajectory on which Dumbarton Oaks is hurtling forward and upward. The place was founded for advanced research. No one who respects strong and solid tradi- tions would wrench it from the scholarship enshrined in its library, archives, and research collections; at the same time, it was designed to welcome a larger public. These two events give tribute to this broader engagement. To serve the greater good, Dumbarton Oaks now cooperates vigorously with local schools. It is electrifying to watch postdoc- toral and postgraduate fellows help students enjoy and learn from our gardens and museum collections. On May 16, we hosted a gath- ering with delegates from the DC Collaborative. -

Home of the Humanities at a Serene Harvard Outpost, Scholars find Fertile Ground for Byzantine, Pre-Columbian, and Landscape Studies

Home of the Humanities At a serene Harvard outpost, scholars find fertile ground for Byzantine, pre-Columbian, and landscape studies. by ELIZABETH GUDRAIS On a wintry Wednesday evening, Maria Mavroudi is delivering a lecture on Byzantine science. Using ev- idence from texts and artifacts, she sketches an alter- nate history, one that competes with the common ac- count that the Byzantine empire’s inhabitants were less advanced than their contemporaries in their use and understanding of the sciences. Mavroudi reports that Ptolemy’s Geography, which was produced in Roman Egypt in the second century A.D. and describes a system of coordinates similar to modern latitude and longitude, survives in 54 Greek manuscripts. She argues that the typical explanation of why the text was reproduced—merely to preserve it for Ofuture generations—is wrong, and makes a case that the real purpose was to produce a manual for contem- porary use. She cites texts that describe the richness of Constantinople’s libraries, and others that mention wooden astrolabes; time and the elements, she says, may have erased the evidence of Byzantium’s use of scientific in- Byzantine studies, per se, from Harvard; four di≠erent depart- struments made from this perishable material. Byzantine science, ments—history, classics, art history, and Near Eastern studies— she says, has gone unacknowledged not because it did not exist, were involved. And the setting for her lecture is the world’s fore- but because studying it requires such diverse expertise: knowledge most center of Byzantine scholarship: Dumbarton Oaks, an estate of languages, of Byzantine history, of the history of science. -

Letterhead and Billhead in the Atwater Collection

LETTERHEAD AND BILLHEAD IN THE ATWATER COLLECTION BOX ONE P.L. ABBEY CO. (Kalamazoo, Mich.) C.W. ABBOTT & Co. (Baltimore, Md.) TRUMAN WALES ABELL (Claremont, N.H.) ACTINA APPLIANCE CO. (Kansas City, Mo.) ADLER, FURST & CO. (St. Louis, Mo.) ADLERIKA CO. (Springfield, Minn.) AGNES BOTANIC CO. (New York, N.Y.) AERATED OXYGEN COMPOUND CO. (Nashua, N.H.) W.W. ALEXANDER & CO. (Akron, Ohio) ALKAVIS COMPANY (Detroit, Mich.) ALLAIRE, WOODWARD & CO. (New York, N.Y.; Peoria, Ill.) F.S. ALLEN (New York, N.Y.) ALPHA MEDICAL INSTITUTE (Cincinnati, Ohio) [see also Thomas W. Graydon] AMERICAN ANTI-GRIPINE CO. (Springfield, Mo.) [See also Anti-Gripine Co.] AMERICAN CHEMICAL CO. (Sidney, Ohio) AMERICAN DRUGGISTS SYNDICATE (New York, N.Y.) AMERICAN EYE SALVE CO. (Fredonia, N.Y.) AMERICAN HERB CO. (Washington, D.C.) AMERICAN HERBAL MEDICINE CO. (New York, N.Y.) AMERICAN MANUFACTURING CO. (Brooklyn, N.Y.) ANTI-GRIPINE CO. (Springfield, Mo.) [See also American Anti-Gripine Co.] ARLINGTON CHEMICAL CO. (Yonkers, N.Y.) M.L. ARMSTRONG (Harshaville, Pa.; Mercer, Pa.) SETH ARNOLD (Woonsocket, R.I.) ARNOLD & HENKELMAN (Sandusky, Ohio) JAMES S. ASPINWALL (New York, N.Y.) C.W. ATWELL (Portland, Maine) MOSES ATWOOD (Georgetown, Mass.) AUGAUER BITTERS CO. (Chicago, Ill.) AUSTIN, NICHOLS & CO. (?) J.C. AYER & CO. (Lowell, Mass.) B.H. BACON CO. (Rochester, N.Y.) BACORN CO. (Elmira, N.Y.) J.B. BAIRD (Louisville, Ky.) CHARLES A. BAKER (Fall River, Mass.) H.J. BAKER & BRO. (New York, N.Y.) BAKER CASTOR OIL CO. (New York, N.Y.) BALLARD SNOW LINIMENT CO. (St. Louis, Mo.) ROBERT BARKER & CO. (Philadelphia, Pa.) BARKER, MOORE & MEIN (Philadelphia, Pa.) DEMAS BARNES (New York, N.Y.) BARNETT & LION (New Orleans, La.) W.H. -

Dumbarton Oaks Annual Report, 2012–2013

dumbarton oaks research library and collection 2012–2013 dumbarton oaks research library and collection Annual Report 2012–2013 © 2014 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. ISSN 0197-9159 Cover: Project drawing for the Pre-Columbian wing, ca. 1960. Drawing by Philip Johnson Associates. Frontispiece: Objects on display in the Pre-Columbian wing, 2010. Photograph by Alexandre Tokovinine. www.doaks.org/publications/annual-reports Contents From the Director 7 Director’s Office 13 Fellowships, Project Grants, and Research Stipends 21 Fellowship Reports 33 Byzantine Studies 65 Garden and Landscape Studies 81 Pre-Columbian Studies 91 Library 101 Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives 113 Museum 121 Gardens 137 Publications 143 Friends of Music 151 Finance, Garden Gate, and Information Technology 155 Trustees for Harvard University, Executive Committee, Honorary Affiliates, Senior Fellows, and Staff 161 From the Director When my first term as director of Dumbarton Oaks began, six and a half years ago, I counted blithely on not having to expend much time or energy on the physical plant. After all, we were wrapping up a long campus renewal project that my predecessor, Professor Edward Keenan of Harvard University, had overseen with magnificent results. Instead of meddling with real estate development, my intention was to focus resolutely on people and scholarly programming: that is what my training and experience had prepared me to handle. But it did not take long to realize that human beings demand feeding, heating and cooling, plumbing, lighting, internet connections, and much else that pertains to our physicality, and that the Achilles’ heel in our little body public was our residential housing for fellows. -

Annual Report 2008–2010 | Dumbarton Oaks Research Library

dumbarton oaks dumbarton oaks research library and collection • 2008–2010 • • 2008–2010 w ashington. d.c. At Dumbarton Oaks you have created something very beautiful, It will remain a monument to your taste, knowledge and very special both in the garden and inside the house. understanding—a delight to all who visit it and a great resource to those who are fortunate enough to work there. Robert Woods Bliss to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 1940 dumbarton oaks research library and collection Annual Report 2008–2010 Contents Trustees for Harvard University 9 From the Director 11 Fellowships and Project Grants 23 Byzantine Studies 35 Garden and Landscape Studies 57 Pre-Columbian Studies 67 Publications 83 Library 89 ©2011 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Museum 95 Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. ISSN 0197-9159 Docents 108 Friends of Music 111 Project Editor: Lisa Wainwright Design: Kathleen Sparkes and Lisa Wainwright Gardens 115 Photography: Joseph Mills, Alexandre Tokovinine Facilities 121 Cover: courtesy Outdoor Illuminations / Steve Francis photography Finance and Information Technology 125 Page 2–3: Dumbarton Oaks Garden, Cherry Hill. Dumbarton Oaks Staff 129 Trustees for Harvard University Drew Gilpin Faust, President James F. Rothenberg, Treasurer Nannerl O. Keohane Patricia A. King William F. Lee Robert D. Reischauer Robert E. Rubin Administrative Committee Ingrid Monson, Acting Chair William Fash Sara Oseasohn Michael D. Smith Jan M. Ziolkowski Director Jan M. Ziolkowski From the Director A Home for the Humanities: Past, Present, and Future In our last institutional report, I enumerated activities from the first year and a half of my directorship. -

The Oaks News, March 2016 Not Displaying Correctly? View This Email in Your Browser

The Oaks News, March 2016 Not displaying correctly? View this email in your browser. Upcoming Events Film Screening: Containment (2015) Directed and Produced by Peter Galison and Robb Moss Wednesday, March 23, 2016, 5:30–8:30 p.m. Oak Room, Dumbarton Oaks Fellowship House 4th Floor, 1700 Wisconsin Avenue NW Part wake-up call, part observational documentary, part sci-fi graphic novel, Containment, a new film from Harvard professors and filmmakers Peter Galison and Robb Moss (Secrecy, 2008), tracks our most imaginative attempts to plan for our radioactive future and reveals the startling failure to manage waste in the present, as epitomized by the Fukushima disaster. Galison will be present and will take questions after the screening. This film is presented as part of the Environmental Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital. Find out more about Containment and its creators on our website; book tickets here. Private Collecting and Public Display Art Museums in the Nation’s Capital in the Early Twentieth Century April 8–9, 2016 Music Room, Dumbarton Oaks 1703 32nd Street NW Register at this link. The conference will explore the aesthetic, philosophical, and ideological sources that shaped art collecting in early twentieth-century America, focusing on collections in Washington, D.C., especially the Phillips Collection, Freer Gallery, Textile Museum, Dumbarton Oaks, National Gallery of Art, and Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens. The founders of these collections advanced distinct notions of cultural identity by collecting and displaying art outside the general canon of early twentieth-century art collecting. Papers will contextualize the individual foundations within the broader history of related American institutions, focusing on the modernist notion of art collecting as a form of self-expression, a visual rendition of a collector’s worldview, and a specific understanding of the course of history. -

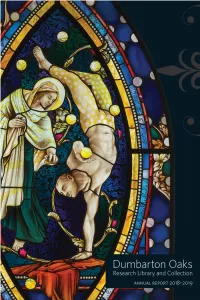

Annual Report

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 2018–2019 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Annual Report 2018–2019 © 2019 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC ISSN 0197-9159 Cover: Stained glass window created for the exhibit Juggling the Middle Ages by Jeffrey Miller, Sarah Navasse, and Jérémy Bourdois for Atelier Miller, Chartrettes, France, 2018. Photograph by Jérémy Bourdois, 2018. Frontispiece: A quiet afternoon in the Orangery www.doaks.org/about/annual-reports Contents From the Director 7 Director’s Office 11 Academic Programs 19 Plant Humanities Initiative 37 Fellowship Reports 43 Byzantine Studies 67 Garden and Landscape Studies 79 Pre-Columbian Studies 91 Library 99 Publications and Digital Humanities 105 Museum 115 Garden 121 Music at Dumbarton Oaks 125 Facilities, Finance, Human Resources, and Information Technology 129 Administration and Staff 137 From the Director Over the next three years, two paramount goals will inform Dumbar ton Oaks and provide rallying points. First, access. Never has it mat tered as much as presently. We have been entrusted resources to maintain, develop, and study, and we carry an obligation to make them approachable. Researchers flock from near and far, often funded by fellowships. Other audiences include visitors and school groups drawn to our garden and museum. Second, teamwork. Through intelligent and intensified collaboration, our upward trajectory will continue. To assist more individuals demands heightened efficiency. We can accomplish more by taking combined action, both within individual departments and across them. Dumbarton Oaks boasts many specializations, with historic garden, art museum, special collections, research library, and photographic and documentary archives, and with Byzantine, PreColumbian, and Garden and Land scape Studies.