My Journey from Silence to Solidarity Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conspirologia E O Link Oculto Da Contracultura Com As Estrelas TROPAS DE CHOQUE DO VATICANO: a GUERRA SANTA DE JOÃO PAULO Ricardo Rosas II PÁGINA – 157 Cletus Nelson

2 Índice APOCALIPSE HIGH TECH Por Vladimir Cunha PÁGINA – 21 A AMÉRICA É UMA RELIGIÃO EUA MANTÉM EM SEGREDO ARMAS NÃO-LETAIS George Monbiot Debora MacKenzie, da New Scientist PÁGINA – 6 PÁGINA – 23 A DEPURAÇÃO DA TERRA BOATO FORTE Ricardo Concha Traverso Peter Burke PÁGINA – 25 PÁGINA – 9 A GUERRA DOS CÓDIGOS E SUAS ARMAS AS CINCO DIFICULDADES PARA ESCREVER A VERDADE Giselle Beiguelman Bertold Brecht PÁGINA - 28 PÁGINA - 12 A SOLUÇÃO FINAL CAPITALISTA A FAMÍLIA BUSH E O PREÇO DO SANGUE DERRAMADO PELOS NAZISTAS Laymert Garcia dos Santos Victor Thorn - Babel Magazine PÁGINA – 15 PÁGINA - 35 AFINAL, ONDE ESTÁ A VERDADE? Cláudio Malagrino CONHECIMENTO TOTAL DA DESINFORMAÇÃO (1) – Conflito e Controle na Infosfera PÁGINA – 18 Konrad Becker PÁGINA - 41 3 AS OITO CARACTERÍSTICAS DOS CULTOS QUE ATUAM NO CONTROLE INFORMAÇÃO E CONTRA-INFORMAÇÃO MENTAL Roberto Della Santa Barros Randall Watters PÁGINA – 63 PÁGINA – 43 DETECTANDO A DESINFORMAÇÃO, SEM RADAR CHEGA DE ROCK N´ROLL Gregory Sinaisky Stewart Home PÁGINA – 45 PÁGINA – 67 BIG BROTHER WANTS YOU – Echelon, um megassistema eletrônico dos EUA, patrulha o mundo MANIPULAÇÕES PÚBLICAS – Duplientrevista com Sheldon Ramptom José Arbex Jr. Daniel Campos PÁGINA – 47 PÁGINA – 68 UM OUTRO LADO DA HISTÓRIA – Uma entrevista com André Mauro (showdalua.com) COMO PODE UM HOMEM DE MARKETING LANÇAR UM PRODUTO QUE PÁGINA – 50 NÃO PRECISA EXISTIR? Por Ricardo Vespucci MONSTERS, INC. Chris Floyd PÁGINA – 72 PÁGINA – 60 4 MENTIRAS DE ESTADO O STATUS ONTOLÓGICO DA TEORIA DA CONSPIRAÇÃO Ignacio Ramonet Hakim Bey PÁGINA -

Our Brochure

Wom en’ ality s M xu in se is o tr m ie o s H Chu rch rch ea A es u R th o ri ty Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research ality Sexu iritu al Sp Et an hi ti cs is hr C Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Who We Are 5 Legal Entity What We Do 6 Aims and Objectives Current Projects 8 Developing the Magisterium - Pushing the Boundaries for Doing Theology History and Achievements 9 Work on Spirituality Work on Women’s Ordained Ministries Work on Church Authority; Sexual Ethics; Spirituality, Science and Faith Scholarly Publications Academic Declarations and Media Appearances Catherine of Siena Virtual College Is it Legitimate to Re-Examine Some Papal Teachings? 14 A Case Study - Is Slavery God’s Will? We Make A Difference 15 Costing and Financing 16 Planning for the Future How You Can Help 17 Financial Donations Sponsor a Topic How to Make a Donation Legacy Volunteering Appendix 1 20 Appendix 2 21 Photo credits 22 Patrons 23 2 Letter from the Director Like all living institutions the Roman Catholic Church needs those who love her without question, and those who love her with questions. In order to survive as a force for good in the world, the Roman Catholic Church needs to update herself, and to do so she needs uncensored original and constructive thinking. As an independent think-tank, the Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research (WICR) promotes such thinking. We produce cutting-edge theological research by coordinating leading academics to collaborate on reports tackling the Church’s officially uncomfortable, difficult, and disputed areas: women’s ordained ministries, sexual ethics, and church authority. -

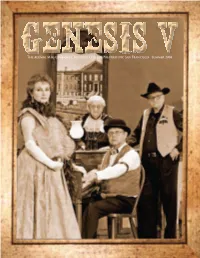

Summer 2008 Edition of Genesis V

The Alumni Magazine of St. Ignatius College Preparatory, San Francisco Summer 2008 Duets: SI Grads Working in Tandem First Words THIS past semester, SI has seen the departure Mark and Bob gave of themselves with generosity of veteran board leaders, teachers and administrators – and dedication that spoke of their great love for SI. The men and women dedicated to advancing the work of SI administration, faculty and alumni are immensely grateful to – and the arrival of talented professionals to continue in them and to their wives and families who supported them so their stead. selflessly in their volunteer efforts to advance the school. Mr. Charlie Dullea ’65, SI’s first lay principal, is stepping Rev. Mick McCarthy, S.J. ’82, and Mr. Curtis down after 11 years in office. He will work to help new teachers Mallegni ’67 are, respectively, the new chairmen of the learn the tricks of the trade and teach two English classes. board of trustees and the board of regents. Fr. McCarthy is Taking his place is Mr. Patrick Ruff, a veteran administrator a professor of classics and theology at SCU. Mr. Mallegni at Boston College High School. In this issue, you will find is a past president of the Fathers’ Club, a five-year regent, stories on both these fine Ignatian educators. and, most recently, chairman of the search committee for Steve Lovette ’63, vice president and the man who the new principal. helped such luminaries as Pete Murphy ’52, Al Wilsey ’36, Janet and Nick Sablinsky ’64 are leaving after decades Rev. Harry Carlin, S.J. -

Fr.John Dear Sj and Fr.Roy Bourgeois Mm Education for Discipleship

The Canadian Forum on Theology and Education The University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario. Thursday May 27th (7-30pm) to Saturday May 29th (12 noon) Fr.John Dear sj and Fr.Roy Bourgeois mm Education for Discipleship www.cfotae.ca Basic Registration includes: Two lunches, coffee breaks and wine and cheese reception. $190 Accommodation & Meals includes: Two nights single accommodation, two breakfasts and two suppers. $170 Registration & Accommodation (all of the above) $360 You can register for the 2010 session of The Canadian Forum on Theology and Education in 3 ways: on-line, fax, or Canada Post. John Quinn Coordinator 905-934-9115 [email protected] John Dear's work for justice and peace has taken him to El Salvador, where he lived and worked in a refugee camp in 1985; to Guatemala, Nicaragua, Haiti, the Middle East, and the Philippines; to Northern Ireland where he lived and worked at a human rights center for a year; and to Iraq, where he led a delegation of Nobel Peace Prize winners to witness the effects of the deadly sanctions on Iraqi children. He has run a shelter for the homeless in Washington, DC; and served as Executive Director of the Sacred Heart Center, a community center for disenfranchised women and children in Richmond, Virginia. In 2008 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. After college Fr. Roy served as a Naval Officer for four years--two years at sea, one year at a NATO station in Europe, and one year of shore duty in Vietnam. He received the Purple Heart. After military service, Fr. -

T--K~LEI~HOU~SS~

.. t--K~LEI~HOU~SS~ VOL xx, NO 146 KWAJALEIN MISSILE RANGE, MARSHALL ISLANDS MONDAY, AUGUST 1, 1983 Maneuvers In Honduras Are 'Routine' u.s. Puts Aircraft Carrier Battle Group Reagan And Weinberger Say WASHINGTON (UPI) -- Presldent Reagan and Defense On 'Standby for Operations' Secretary Caspar Welnberger sald the mllltary man WASHINGTON (UPI) -- The Unlted States today put an alrcraft carrler battle euvers thlS month In Honduras are routlne, but lt group on standby In the Medlterranean and ordered a reVlew of mllltary ald to wlll be the flrst tlme the Unlted States has con Chad In response to Chadlan charges that Llbyan warplanes attacked one of ltS ducted land ererClses for SlX months at a stretch cltles The ground exerClses are lntended as a slgnal to The nuclear-powered carrler Elsenhower steamed In the central Medlterranean the leftlst Nlcaraguan reglme to stop supportlng "on s ta ndby for operat lOns" 1n the event L1 bya renews a 1r s t n kes aga 1ns t 1ts gu~rrlllas In the area, partlcularly In El Salva southern nelghbor, Pentagon offlclals sald They sald, however, the ShlP and dor Naval eXErClses are already under way ltS escorts have not been placed on alert The exerCl~e wlll last SlX months and at one In addltlon, the conventlonally-powered carrler Coral Sea was In the same pOlnt, posslbly In November, wlll lnvolve between area after departlng from Naples, Italy, Sunday, as prevlously scheduled, the 3,000 and 4,000 Amerlcan offlclals sald NATO Calls For combat troops It wlll The Elsenhower was Reagan's Civil Rights Commitment -

News from National Priest of Integrity—Nominees

In the Vineyard, December 12, 2009 News from National Roman Missal Controversy Voice of the Faithful received a letter last week from Father Michael Ryan, pastor of St James Cathedral in Seattle, Washington. Father Ryan is concerned about the controversial new translations of the Roman Missal. He has published an article in the December 14 issue of America Magazine entitled “What if we just said wait? The case for a grassroots review of the new Roman Missal.” (http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=12045) Father Ryan has also set up a website www.whatifwejustsaidwait.org for people to make comments that he hopes to bring to U.S. Bishops to encourage further thought on this issue. The National Catholic Reporter also ran an article on this issue in October. http://ncronline.org/news/faith-parish/slavishly-literal-translation-missal-criticized Priest of Integrity—Nominees Two priests, Reverend Joseph Fowler and Reverend Donald Cozzens, were honored as Priests of Integrity at VOTF’s National Conference, “Making our Voices Heard,” held on Long Island NY on October 30-31, 2009. Along with these two, four other priests were nominated for recognition. In this and following issues of In the Vineyard we will honor these priests (in alphabetical order) with articles about the work that they are doing for others and for the good of our church. Reverend Roy Bourgeois was enthusiastically nominated by the New York City affiliate of VOTF. His is a name not unknown to many of us, and he has a broad base of support from the people he serves. -

Roman Catholic Womenpriests and the Problem of Women’S Ordination

TRANSGRESSIVE TRADITIONS: ROMAN CATHOLIC WOMENPRIESTS AND THE PROBLEM OF WOMEN’S ORDINATION Jill Marie Peterfeso A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Laurie Maffly-Kipp Julie Byrne Todd Ochoa Tony Perucci Randall Styers Thomas A. Tweed ©2012 Jill Marie Peterfeso ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JILL MARIE PETERFESO: Transgressive Traditions: Roman Catholic Womenpriests and the Problem of Women’s Ordination (Under the direction of Laurie Maffly-Kipp) Although the Roman Catholic Church bars women from ordained priesthood, since 2002 a movement called Roman Catholic Womenpriests (RCWP) claims to have ordained approximately 120 women as deacons, priests, and bishops in Europe, North America, and Latin America. Because the women deliberately break Canon Law—and specifically c. 1024, which reads, “Only a baptized man can validly receive sacred ordination”—RCWP acknowledges that its ordinations are illegal, but the group claims nonetheless to perform valid ordinations because they stand in the traditional line of apostolic succession. They retain the modifier “Roman” to signal their lineage within Roman Catholic tradition, yet RCWP’s stated goal is not simply to insert women into the existing Church structures, but rather to “re-imagine, re-structure, and re-shape the priesthood and therefore the church.” This dissertation investigates the -

Roy Bourgeois Founder of School of the Americas Watch (SOAW) and Supporter of Women’S Ordination and LGBT Equality

Nationally Recognized Activist Roy Bourgeois Founder of School of the Americas Watch (SOAW) and supporter of women’s ordination and LGBT equality “Peace, Justice, Equality and Conscience in Latin America Sponsored by ROCLA (Rochester Committee on Latin America) Roy Bourgeois is an impassioned, eloquent and tireless activist for human Wednesday, May 6, 2015 rights throughout the Western Hemisphere. He served as a Catholic priest in Bolivia for 5 years until he was expelled for standing with the poor in 7:00 pm their struggle for human rights. In 1990, he founded the School of the America’s (SOA) Watch to shut down the school where the military perpetrators of genocide, repression and torture in Latin America were Downtown United trained to conduct low-intensity warfare campaigns against democratic Presbyterian Church movements in the 1980s. 121 N. Fitzhugh Street He has spent 4 years in Federal prison for his nonviolent protests Rochester, NY against the SOA and produced a documentary about the SOA, (handicap accessible) called “School of Assassins,” which was nominated for an Academy. He was nominated for a Nobel Grania Marcus, Prize in 2010. More recently, he [email protected], has advocated for LGBT equality (917) 579-0199 and the ordination of women and Marilu Aguilar, has been expelled from the priesthood after 40 years. [email protected], (585) 880-2847 In March, Roy and an SOA Watch delegation of 20 met with El Salvadoran President Ceren and other human rights leaders. Roy and others met with 5 of 17 ("Las 17") women who were imprisoned for 30 years for having miscarriages. -

December 2009

DECEMBER, 2009 1 A MODESTO PEACE/LIFE CENTER PUBLICATION DECEMBER, 2009 VOLUME XXII, NO. 4 INSIDE CONNECTIONS “Let there be Peace Annual Modesto Peace/Life Center LOCAL EVENTS . 2 on Earth and Let it Holiday Party Potluck DEFICIT HAWKS . 3 begin with me” & Song Circle LIVING LIGHTLY . 4 By JANA and MICHAEL CHIAVETTA RIVERS OF BIRDS . .5 This is the inspiration and belief behind the formation Friday, December 11, 2009 of the Modesto Peace/Life Center Social Justice Youth 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. CHARTER FOR COMPASSION . 6 Gathering. This title is a bit cumbersome but this is what we are calling the meeting that is occurring on the first Tuesday At the home of Dan & Alice Onorato THE OTHER WAR . .7 of each month at the Modesto Peace/Life Center from 6-7 1532 Vernon, Modesto AFGHANISTAN . 8 P.M. The “gathering” is open to high school students who are interested in social justice issues such as peace, the en- GATHERING OF VOICES . 9 vironment, civil rights and community involvement. At the Bring your festive spirit Social Justice Youth Leadership Conference, held at the end DIALOGUE . 10 of September, high school participants attended a workshop and food to share! GAZA FREEDOM MARCH . 11 that introduced them to the concept of becoming a “Peace Maker.” The hope was that enough students would be inter- Information: 526-5436 ested enough to continue the training at a monthly meeting. The first gathering was held in October and a grand total of one student attended. We were not discouraged and held the The next phase of second meeting on November 3rd and six students attended. -

Yesus Kristus

EDISI REVISI 2018 SD KVIELAS Hak Cipta © 2018 pada Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Dilindungi Undang-Undang Disklaimer: Buku ini merupakan buku guru yang dipersiapkan Pemerintah dalam rangka implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Buku guru ini disusun dan ditelaah oleh berbagai pihak di bawah koordinasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, dan dipergunakan dalam tahap awal penerapan Kurikulum 2013. Buku ini merupakan “dokumen hidup” yang senantiasa diperbaiki, diperbaharui, dan dimutakhirkan sesuai dengan dinamika kebutuhan dan perubahan zaman. Masukan dari berbagai kalangan yang dialamatkan kepada penulis dan laman http://buku.Kemendikbud.go.id atau melalui email [email protected] diharapkan dapat meningkatkan kualitas buku ini. Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) Indonesia. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Pendidikan Agama Katolik dan Budi Pekerti : buku guru / Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Edisi Revisi. Jakarta : Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 2018. viii, 256 hlm. : ilus. ; 25 cm. Untuk SD Kelas VI ISBN 978-602-282-217-2 (jilid lengkap) ISBN 978-602-282-223-3 (jilid 6) 1. Katolik -- Studi dan Pengajaran I. Judul II. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan 282 Penulis Naskah : Marianus Didi Kasmudi dan F.X. Dapiyanta Nihil Obstat : F.X. Adi Susanto, S.J. 14 Agustus 2014 Imprimatur : Mgr. John Liku Ada 21 Agustus 2014 Penelaah : Matheus Benny Mithe, Matias Endar Suhendar, Vincentius Darmin Mbula, dan Antonius Sinaga. Pereview : Yosephin Sudarni Penyelia Penerbitan : Pusat Kurikulum dan Perbukuan, Balitbang, Kemendikbud. Cetakan Ke-1, 2015 (ISBN 978-602-153-027-6) Cetakan Ke-2, 2018 (Edisi Revisi) Disusun dengan huruf Baar Metanoia, 12 pt. Kata Pengantar Sebagai tindak lanjut dari perubahan atau revisi kurikulum 2013 yang berkembang selama ini, tim penyusun melanjutkan penyusunan Buku Pendidikan Agama Katolik dan Budi Pekerti bagi siswa serta pegangan guru, dengan beberapa perubahan dan penyesuaian, baik berupa isi atau materi maupun kelengkapan penilaian. -

Complete Dissertation.Pdf

VU Research Portal Eikon and Ayat Subandrijo, B. 2007 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Subandrijo, B. (2007). Eikon and Ayat: Points of Encouter between Indonesian Christian and Muslim Perspectives on Jesus. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 EIKŌN AND ĀYAT Points of Encounter between Indonesian Christian and Muslim Perspectives on Jesus Bambang Subandrijo VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT EIKŌN AND ĀYAT Points of Encounter between Indonesian Christian and Muslim Perspectives on Jesus ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. L.M. Bouter, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de faculteit der Godgeleerdheid op woensdag 19 december 2007 om 10.45 uur in het auditorium van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Bambang Subandrijo geboren te Yogyakarta, Indonesië promotoren: prof.dr. -

Bible/Book Studies

1 BIBLE/BOOK STUDIES A Gospel for People on the Journey Luke Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Luke, Jesus is not only the one who announces the Good News of salvation: Jesus is our salvation. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Searching People Matthew Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Matthew, Jesus is the great teacher (Matt. 23:8). But teacher and teachings are inextricable bound together, Matthew tells us. Jesus stands alone as unique teacher because of his special relationship with God: he alone is Son of man and Son of God. And Jesus still teaches those who are searching for meaning and purpose in life today. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Struggling People Mark Novalis Scripture Studies Series “Who do you say that I am? In Mark’s Gospel, no one knows who Jesus is until, in Chapter 8, Peter answers: “You are the Christ.” But what does this mean? The rest of the Gospel shows what kind of Christ or Messiah Jesus is: he has come to suffer and die for his people. Teaching on discipleship and predictions of his death point ahead to the focus of the Gospel-the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor Beautiful Bible Stories Beautiful Bible Stories by Rev. Charles P. Roney, D.D. and Rev. Wilfred G. Rice, Collaborator Designed to stimulate a greater interest in the Bible through the arrangement of extensive References, Suggestions for Study, and Test Questions.