THE GLUCONIC ACID OXIDIZING SYSTEM of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oh Ho Oh Oh Oh Oh O Ho Ch3o N N H O Ho Oh Oh Oh Oh O Ho Ch3o N N

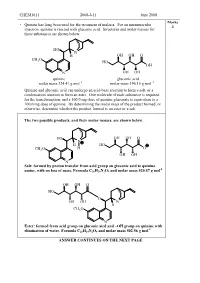

CHEM1611 2008-J-11 June 2008 Marks • Quinine has long been used for the treatment of malaria. For an intramuscular 4 injection, quinine is reacted with gluconic acid. Structures and molar masses for these substances are shown below. HO N H OH OH O CH O 3 HO OH N OH OH quinine gluconic acid molar mass 324.41 g mol –1 molar mass 196.16 g mol –1 Quinine and gluconic acid can undergo an acid-base reaction to form a salt, or a condensation reaction to form an ester. One molecule of each substance is required for the transformation, and a 160.0 mg dose of quinine gluconate is equivalent to a 100.0 mg dose of quinine. By determining the molar mass of the product formed, or otherwise, determine whether the product formed is an ester or a salt. The two possible products, and their molar masses, are shown below. HO OH OH O N H HO CH3O H O OH OH N Salt: formed by proton transfer from acid group on gluconic acid to quinine -1 amine, with no loss of mass. Formula C 26 H26 N2O9 and molar mass 520.57 g mol OH OH O HO O OH OH N H CH3O N Ester: formed from acid group on gluconic aicd and –OH group on quinine with -1 elimination of water. Formula C 26 H24 N2O8 and molar mass 502.56 g mol ANSWER CONTINUES ON THE NEXT PAGE CHEM1611 2008-J-11 June 2008 100.0 mg of quinine corresponds to: ̡̭̳̳ ̊̉̉.̉Ɛ̊̉ ̌ ̧ number of moles = Ɣ = 3.083 × 10 -4 mol ̡̭̯̬̲ ̡̭̳̳ ̌̋̍.̍̊ ̧ ̭̯̬ ̊ 160.0 mg of the salt product corresponds to: ̡̭̳̳ ̊̏̉.̉Ɛ̊̉ ̌ ̧ number of moles = Ɣ = 3.074 × 10 -4 mol ̡̭̯̬̲ ̡̭̳̳ ̎̋̉.̎̐ ̧ ̭̯̬ ̊ 160.0 mg of the ester product corresponds to: ̡̭̳̳ ̊̏̉.̉Ɛ̊̉ ̌ ̧ number of moles = Ɣ = 3.184 × 10 -4 mol ̡̭̯̬̲ ̡̭̳̳ ̎̉̋.̎̏ ̧ ̭̯̬ ̊ As the dosages are the same, it must be the salt which is being administered. -

Promising Strain of Acinetobacter from Soil for Utilization of Gluconic Acid Production Topraktaki Gelecek Vaadeden Acinetobacte

S. Dinç et al. / Hacettepe J. Biol. & Chem., 2017, 45 (4), 603-607 Promising Strain of Acinetobacter from Soil for Utilization of Gluconic Acid Production Topraktaki Gelecek Vaadeden Acinetobacter Suşunun Glukonik Asit Üretiminde Kullanımı Research Article Saliha Dinç 1,2*, Meryem Kara2,3, Mehmet Öğüt3, Fatih Er1, Hacer Çiçekçi2 1Selcuk University Cumra School of Applied Sciences, Konya-Turkey. 2Selcuk Uni. Advanced Technology Research and Application Center, Konya-Turkey. 3Selcuk University Cumra Vocational High School, Konya-Turkey. ABSTRACT luconic acid, a food additive, is used in many foods to control acidity or binds metals such as calcium, Giron. Acinetobacter sp. WR326, newly isolated from soil possesses high phosphate solubilizing activity and do not require pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) for glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) activity as cofactor In this study the gluconic acid production potential of this bacterium was investigated. Firstly, Acinetobacter sp. WR326 was incubated in tricalcium phosphate medium (TCP) with varying glucose concentrations (100, 250, 500 mM), at a temperature of 30°C for 5 days (120 hours). The highest gluconic acid yield (59%) was found at a glucose concentration of 100 mM. Then three different levels of gluconic acid addition to the medium (50, 100, 200 mM) were tested. When Acinetobacter sp. WR326 strain was cultivated with a 100 mM glucose and 100 mM gluconic acid the yield increased to 95.27%. In any trials 2 -keto D-gluconic acid, causes problems in processing and purification of the gluconic acid, was not detected in the medium. As a conclusion, Acinetobac- ter sp. WR326 may be considered novel potential bacterial strain for gluconic acid production. -

The Possibility of Recovering of Hydroxytyrosol from Olive Milling Wastewater by Enzymatic Bioconversion 265

ProvisionalChapter chapter 14 The PossibilityPossibility of of Recovering Recovering of Hydroxytyrosolof Hydroxytyrosol from fromOlive Milling Wastewater by Enzymatic Bioconversion Olive Milling Wastewater by Enzymatic Bioconversion Manel Hamza and Sami Sayadi Manel Hamza and Sami Sayadi Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/64774 Abstract This chapter discusses an innovative approach to obtain liquid fractions from olive mill wastewater (OMW) rich in hydroxytyrosol. The method is based on bioconversion combined with membrane separation techniques. An enzymatic bioconversion of three types of OMW was tested. TheS total volumes of OMW are 15 and 40 L. The reaction was monitored in mechanically stirred systems for 2 h at 50°C. Maximum hydroxytyr‐ osol concentrations of about 1.53, 0.83 and 0.46 g/L in the presence of 5 IU Aspergillus niger β‐glucosidase per milliliter from North OMW and South OMW were procured by two different olive millings, which are milling super press (MSP) and milling continuous chain (MCC), respectively. Enzymatic pretreatment was followed by two tangential flow membrane separation stages, microfiltration (MF) and ultrafiltration (UF). The ultrafiltration permeate was concentrated by evaporation at 45°C for 2 h. The latter exhibited a chemical oxygen demand (COD) level of 48.44 g/L. The UF permeate dehydration increased the hydroxytyrosol concentration to 7.2 g/L. A new natural product that contains some minerals beneficial to health and devoid of heavy metals or chemicals was obtained by this innovative work which describes an environmentally friendly process at pilot‐scale. -

Wöhler Synthesis of Urea

Wöhler synthesis of urea Wöhler, 1928 – – + + NH Cl + K N C O 4 NH4 N C O O H2N NH2 Friedrich Wöhler Annalen der Physik und Chemie 1828, 88, 253–256 Significance: Wöhler was the first to make an organic substance from an inorganic substance. This was the beginning of the end of the theory of vitalism: the idea that organic and inorganic materials differed essentially by the presence of the “vital force”– present only in organic material. To his mentor Berzelius:“I can make urea without thereby needing to have kidneys, or anyhow, an animal, be it human or dog" Friedrich Wöhler, 1880-1882 Polytechnic School in Berlin Support for vitalism remained until 1845, when Kolbe synthesized acetic acid Polytechnic School at Kassel from carbon disulfide University of Göttingen Fischer synthesis of glucose PhHN N O N O NHPh Br aq. HCl Δ PhNH2NH2 HO H HO H O Br "α−acrose" H OH H OH H OH H OH CH2OH CH2OH α−acrosazone α−acrosone an “osazone” (osazone test for reducing sugars) Zn/AcOH OH OH CO2H CHO O HO H HO H OH Br2 HO H HO H Na-Hg HO H HNO3 HO H H OH H OH H OH H OH then resolve H O+ H OH via strychnine H OH H OH 3 H OH CH2OH salts CH2OH CH OH CH2OH 2 D-Mannonic acid DL-Mannose DL-Mannitol DL-Fructose quinoline • Established stereochemical relationship CO2H CHO H OH H OH between mannose and glucose Na-Hg HO H HO H (part of Fischer proof) H OH + H OH H3O • work mechanisms from acrosazone on H OH H OH Emil Fischer, 1852-1919 CH2OH CH2OH University of Munich (1875-81) D-Gluconic acid D-Glucose University of Erlangen (1881-88) University of Würzburg (1888-92) University of Berlin (1892-1919) Fischer, E. -

(Punica Granatum L.) Peel Waste: a Review

molecules Review Processing Factors Affecting the Phytochemical and Nutritional Properties of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peel Waste: A Review Tandokazi Pamela Magangana 1,2 , Nokwanda Pearl Makunga 1 , Olaniyi Amos Fawole 3 and Umezuruike Linus Opara 2,* 1 Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa; [email protected] (T.P.M.); [email protected] (N.P.M.) 2 Postharvest Technology Research Laboratory, South African Research Chair in Postharvest Technology, Department of Horticultural Sciences, Faculty of AgriSciences, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa 3 Postharvest Research Laboratory, Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park, Johannesburg 2006, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-21-808-4064 or +27-21-808-3743 Academic Editors: Ana Barros and Irene Gouvinhas Received: 5 September 2020; Accepted: 7 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020 Abstract: Pomegranate peel has substantial amounts of phenolic compounds, such as hydrolysable tannins (punicalin, punicalagin, ellagic acid, and gallic acid), flavonoids (anthocyanins and catechins), and nutrients, which are responsible for its biological activity. However, during processing, the level of peel compounds can be significantly altered depending on the peel processing technique used, for example, ranging from 38.6 to 50.3 mg/g for punicalagins. This review focuses on the influence of postharvest processing factors on the pharmacological, phytochemical, and nutritional properties of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel. Various peel drying strategies (sun drying, microwave drying, vacuum drying, and oven drying) and different extraction protocols (solvent, super-critical fluid, ultrasound-assisted, microwave-assisted, and pressurized liquid extractions) that are used to recover phytochemical compounds of the pomegranate peel are described. -

Print This Article

Macedonian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 149–160 (2019) MJCCA9 – 775 ISSN 1857-5552 e-ISSN 1857-5625 Received: April 23, 2019 DOI: 10.20450/mjcce.2019.1775 Accepted: October 8, 2019 Original scientific paper IDENTIFICATION AND QUANTIFICATION OF PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS IN POMEGRANATE JUICES FROM EIGHT MACEDONIAN CULTIVARS Jasmina Petreska Stanoeva1,*, Nina Peneva1, Marina Stefova1, Viktor Gjamovski2 1Institute of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Ss Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia 2Institute of Agriculture, Ss Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia [email protected] Punica granatum L. is one of the species enjoying growing interest due to its complex and unique chemical composition that encompasses the presence of anthocyanins, ellagic acid and ellagitannins, gal- lic acid and gallotannins, proanthocyanidins, flavanols and lignans. This combination is deemed respon- sible for a wide range of health-promoting biological activities. This study was focused on the analysis of flavonoids, anthocyanins and phenolic acids in eight pomegranate varieties (Punica granatum) from Macedonia, in two consecutive years. Fruits from each cultivar were washed and manually peeled, and the juice was filtered. NaF (8.5 mg) was added to 100 ml juice as a stabilizer. The samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm and analyzed using an HPLC/DAD/MSn method that was optimized for determination of their polyphenolic fingerprints. The dominant anthocyanin in all pomegranate varieties was cyanidin-3-glucoside followed by cya- nidin and delphinidin 3,5-diglucoside. From the results, it can be concluded that the content of anthocyanins was higher in 2016 compared to 2017. -

Catalytic Oxidation of Glucose with Hydrogen Peroxide and Colloidal Gold As Pseudo-Homogenous Catalyst

Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2016; 43(4) 825 Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2016; 43(4) : 825-833 http://epg.science.cmu.ac.th/ejournal/ Contributed Paper Catalytic Oxidation of Glucose with Hydrogen Peroxide and Colloidal Gold as Pseudo-Homogenous Catalyst: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation Jitrayut Jitonnom [a] and Christoph Sontag *[a] [a] Division of Chemistry, School of Science, University of Phayao, Phayao 56000, Thailand. *Author for correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] Received: 10 July 2013 Accepted: 25 April 2014 ABSTRACT Gold nanoparticles have been proved to act as oxidation catalyst for glucose oxidation, offering a “chemical” synthetic route to gluconic acid and gluconates - nowadays commercially produced by an enzyme catalyzed oxidation. Our investigations of the gold catalyzed oxidation route showed that gold nanoparticles produced by a modified Turkevich method have a high activity for this pseudo-homogenous catalytic reaction. Under mild reaction conditions, glucose could be oxidized in good yields (~70%) and the resulting gluconate could be isolated by column chromatography and precipitation as calcium salt. The catalytic oxidation reaction was found to follow the first-order kinetic with a rate constant of 4.95 h-1, in good agreement with previous finding. The underlying reaction mechanism is discussed, assuming that the formation of a gold-glucose cluster intermediate is a key catalytic step. Several structures of the gold-glucose intermediates were examined using density functional theory methods. The molecular behavior of glucose adsorption in gold colloid solution is present. Keywords: colloidal gold catalyst, glucose oxidation, gold nanoparticle, gluconic acid, DFT 1. INTRODUCTION Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) as highly Catalysis by Au NPs has been emerged effective green catalysts for oxidative by the discovery of gold nanoparticles as processes have become a research topic of highly active supported catalysts for oxidation wide-spread interest in recent years [1-5], of CO into CO2 by atmospheric air [7]. -

The Effect of Iron on Gluconic Acid Production by Aureobasidium Pullulans

The Open Biotechnology Journal, 2008, 2, 195-201 195 Open Access The Effect of Iron on Gluconic Acid Production by Aureobasidium pullulans Savas Anastassiadis1,*, Svetlana V. Kamzolova2, Igor G. Morgunov2 and Hans-Jürgen Rehm3 1Pythia Institute of Biotechnology, Research in Biotechnology (Co.), Avgi/Sohos, 57002 Thessaloniki, Greece and Envi- ronmental Engineering Department of Democritus University of Thrace, 67 100 Xanthi, Greece; 2Institute of Biochemis- try and Physiology of Microorganisms, Russian Academy of Sciences pr-t Nauki 5, Pushchino Moscow Region 142290, Russia and 3Institute of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, University of Münster, Corrensstr. 3, 48149 Mün- ster, Germany Abstract: New processes have been previously described for the continuous and discontinuous production of gluconic acid by Aureobasidium pullulans (de bary) Arnaud. Little is known about the regulatory mechanisms of gluconic acid production by A. pullulans. The response of growth and gluconic acid metabolism to a variable profile of iron concentra- tions was studied with A. pullulans in batch and chemostat cultures. A surprisingly high optimum N-dependent iron ion concentration in the feed medium, in the range between 0.5 mM and 3.0 mM Fe (optimum 1-2 mM), was found to be par- ticular requirement for economically profitable continuous production of gluconic acid with 3 g/l NH4Cl. Increased iron concentration promoted growth on defined glucose medium. 223.3 g/l gluconic acid were continuously produced at a for- mation rate of the generic product (Rj) of 16.8 g/(lh) and a specific gluconic acid productivity (mp) of 2.5 g/(gh) at 13 h residence time (RT) with 1mM iron, compared with 182 g/l reached at 0.1 mM. -

Continuous Gluconic Acid Production by Aureobasidium Pullulans with and Without Biomass Retention

Electronic Journal of Biotechnology ISSN: 0717-3458 Vol.9 No.5, Issue of October 15, 2006 © 2006 by Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso -- Chile Received June 6, 2005 / Accepted November 21, 2005 DOI: 10.2225/vol9-issue5-fulltext-18 RESEARCH ARTICLE Continuous gluconic acid production by Aureobasidium pullulans with and without biomass retention Savas Anastassiadis* Pythia Institute of Biotechnology of Research in Biotechnology Co., Vat. #: 108851559 Avgi/Sohos, 57002 Thessaloniki, Greece Tel. 30 2395 051324 Fax. 30 2395 051470 E-mail: [email protected] Hans-Jürgen Rehm Institute of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology University of Münster Corrensstr. 3, 48149 Münster, Germany (retired Professor) Website: http://www.greekbiotechnologycenter.gr Financial support: The work has been carried out at the Institute of Biotechnology 2 of Research Center Jülich (formerly known as Nuclear Research Center Jülich, Germany) and was financed by Haarmann and Reimer, a daughter company of the company Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany. Keywords: biomass immobilization, continuous fermentation, cross over filtration, gluconic acid fermentation, reaction technique, residence time. Abbreviations: Conversion (%): [(g consumed glucose/g feeding glucose) x 100], dilution of medium glucose by NaOH feeding was considered in the calculations mp: Specific gluconic acid productivity, [g gluconic acid/(g biomass x h)], Rj [g/(l x h)]/biomass concentration (g/l), g/(g x h) Rj: Formation rate of the generic product (volumetric productivity), g gluconic acid/(l -

The Utilization of Urine Processing for the Advancement of Life Support Technologies

44th International Conference on Environmental Systems ICES-2014-138 13-17 July 2014, Tucson, Arizona The Utilization of Urine Processing for the Advancement of Life Support Technologies Elysse N. Grossi1 University of California Santa Cruz, University Associated Research Center NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 and John A. Hogan2 and Michael Flynn3 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 The success of long-duration missions will depend on resource recovery and the self- sustainability of life support technologies. Current technologies used on the International Space Station (ISS) utilize chemical and mechanical processes, such as filtration, to recover potable water from urine produced by crewmembers. Such technologies have significantly reduced the need for water resupply through closed-loop resource recovery and recycling. Harvesting the important components of urine requires selectivity, whether through the use of membranes or other physical barriers, or by chemical or biological processes. Given the chemical composition of urine, the downstream benefits of urine processing for resource recovery will be critical for many aspects of life support, such as food production and the synthesis of biofuels. This paper discusses the beneficial components of urine and their potential applications, and the challenges associated with using urine for nutrient recycling for space application. Nomenclature ATP = adenosine triphosphate BW = black water CO2 = carbon dioxide GAA = guanidoacetic acid H2S = hydrogen sulfide ISS = International Space Station kg/CM-d = kilograms of waste produced per crewmember per day TMAO = trimethylamine N-oxide 1 Synthetic Biology Development Engineer and Researcher, Bioengineering Branch, M/S 239-15, Moffett Field, CA 94035 2 Primary Investigator, Bioengineering Branch, M/S 239-15, Moffett Field, CA 94035. -

Gluconic Acid: Properties, Applications and Microbial Production

S. RAMACHANDRAN et al.: Gluconic Acid: A Review, Food Technol. Biotechnol. 44 (2) 185–195 (2006) 185 ISSN 1330-9862 review (FTB-1651) Gluconic Acid: Properties, Applications and Microbial Production Sumitra Ramachandran1, Pierre Fontanille1, Ashok Pandey2 and Christian Larroche1* 1Laboratoire de Génie Chimique et Biochimique (LGCB), CUST – Université Blaise Pascal, 24, avenue des Landais, B.P. 206, F-63 174 Aubière Cedex, France 2Biotechnology Division, Regional Research Laboratory, CSIR, Trivandrum 695 019, India Received: December 12, 2005 Accepted: March 12, 2006 Summary Gluconic acid is a mild organic acid derived from glucose by a simple oxidation reac- tion. The reaction is facilitated by the enzyme glucose oxidase (fungi) and glucose de- hydrogenase (bacteria such as Gluconobacter). Microbial production of gluconic acid is the preferred method and it dates back to several decades. The most studied and widely used fermentation process involves the fungus Aspergillus niger. Gluconic acid and its deriva- tives, the principal being sodium gluconate, have wide applications in food and pharma- ceutical industry. This article gives a review of microbial gluconic acid production, its properties and applications. Key words: gluconic acid, glucose oxidase, microbial production, Aspergillus niger Introduction Gluconic acid (pentahydroxycaproic acid, Fig. 1) is enzyme is immobilised, e.g. the use of a polymer mem- produced from glucose through a simple dehydrogena- brane adjacent to anion-exchange membrane of low- tion reaction catalysed by glucose oxidase. Oxidation of -density polyethylene grafted with 4-vinylpyridine (1). the aldehyde group on the C-1 of b-D-glucose to a car- However, this approach is not yet common in the indus- boxyl group results in the production of glucono-d-lac- try, and it will not be considered in the review. -

Folder: Product Range

Product Range Bio-based ingredients Vision From nature to ingredients ® About Jungbunzlauer Jungbunzlauer is one of the world’s leading producers of bio degra dable ingredients of natural origin. The Swiss-based, international company’s roots date back to 1867. Today, Jungbunzlauer specialises in citric acid, xanthan gum, gluconates, lactics, specialties, special salts and sweeteners for the food, beverage, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industry, as well as for various other industrial applications. Jungbunzlauer’s products are manufactured utilising natural fermentation processes based on renewable raw materials. All its products can be used, transported and disposed of in a secure and ecologically safe way. Jungbunzlauer operates manufacturing plants in Austria, Canada, France and Germany. A worldwide network of sales companies and distributors with a thorough understanding of target markets and client requirements underlies Jungbunzlauer’s strong market and customer focus. Committed to its rigorous quality standards, Jungbunzlauer guarantees for the excellence and sustainability of its products and services. With their expert knowledge, Jungbunzlauer’s Technical Service, Market Development and Application Technology teams support our customers in resolving their commercial and technical challenges with solutions tailor-made to their individual requirements and with up-to-date technical information on our products. The high-class quality of our products combines decades of experience with up-to-date know-how. Products Based on years of experience and acquired knowledge, Jungbunzlauer offers a broad spectrum of biodegradable key ingredients of natural origin to a diversified range of industries worldwide. Jungbunzlauer’s added value products are manufactured to the highest quality standards and are available in different grades with a wide variety of specifications and performances.