Managing Wildfire Suppression and Safeguarding Crews from COVID-19 Exposures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire Program 2016 Annual Report Weber Basin Job Corps: Above Average Performance In an Above Average Fire Season Brandon J. Everett, Job Corps Forest Area Fire Management Officer, Uinta-Wasatch–Cache National Forest-Weber Basin Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center The year 2016 was an above average season for the Uinta- Forest Service Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Job Corps Participating in nearly every fire on the forest, the Weber Basin Fire Program Job Corps Civilian Conservation Statistics Center (JCCCC) fire program assisted in finance, fire cache and camp support, structure 1,138 students red- preparation, suppression, moni- carded for firefighting toring and rehabilitation. and camp crews Weber Basin firefighters re- sponded to 63 incidents, spend- Weber Basin Job Corps students, accompanied by Salt Lake Ranger District Module Supervisor David 412 fire assignments ing 338 days on assignment. Inskeep, perform ignition operation on the Bear River RX burn on the Bear River Bird Refuge. October 2016. Photo by Standard Examiner. One hundred and twenty-four $7,515,675.36 salary majority of the season commit- The Weber Basin Job Corps fire camp crews worked 148 days paid to students on ted to the Weber Basin Hand- program continued its partner- on assignment. Altogether, fire crew. This crew is typically orga- ship with Wasatch Helitack, fire assignments qualified students worked a nized as a 20 person Firefighter detailing two students and two total of 63,301 hours on fire Type 2 (FFT2) IA crew staffed staff to that program. Another 3,385 student work assignments during the 2016 with administratively deter- student worked the entire sea- days fire season. -

Kneeland Helitack Base

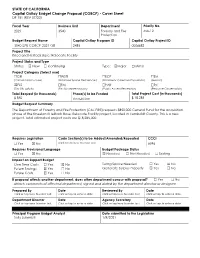

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Capital Outlay Budget Change Proposal (COBCP) - Cover Sheet DF-151 (REV 07/20) Fiscal Year Business Unit Department Priority No. 2021 3540 Forestry and Fire MA-12 Protection Budget Request Name Capital Outlay Program ID Capital Outlay Project ID 3540-078-COBCP-2021-GB 2485 0006682 Project Title Kneeland Helitack Base: Relocate Facility Project Status and Type Status: ☒ New ☐ Continuing Type: ☒Major ☐ Minor Project Category (Select one) ☐CRI ☐WSD ☐ECP ☐SM (Critical Infrastructure) (Workload Space Deficiencies) (Enrollment Caseload Population) (Seismic) ☒FLS ☐FM ☐PAR ☐RC (Fire Life Safety) (Facility Modernization) (Public Access Recreation) (Resource Conservation) Total Request (in thousands) Phase(s) to be Funded Total Project Cost (in thousands) $ 850 Acquisition $ 18,285 Budget Request Summary The Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) requests $850,000 General Fund for the acquisition phase of the Kneeland Helitack Base: Relocate Facility project, located in Humboldt County. This is a new project. Total estimated project costs are $18,285,000. Requires Legislation Code Section(s) to be Added/Amended/Repealed CCCI ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. 6596 Requires Provisional Language Budget Package Status ☐ Yes ☒ No ☒ Needed ☐ Not Needed ☐ Existing Impact on Support Budget One-Time Costs ☐ Yes ☒ No Swing Space Needed ☐ Yes ☒ No Future Savings ☒ Yes ☐ No Generate Surplus Property ☒ Yes ☐ No Future Costs ☒ Yes ☐ No If proposal affects another department, does other department concur with proposal? ☐ Yes ☐ No Attach comments of affected department, signed and dated by the department director or designee. Prepared By Date Reviewed By Date Click or tap here to enter text. -

Oregon Department of Forestry

STATE OF OREGON POSITION DESCRIPTION Position Revised Date: 04/17/2019 This position is: Classified Agency: Oregon Department of Forestry Unclassified Executive Service Facility: Central Oregon District, John Day Unit Mgmt Svc - Supervisory Mgmt Svc - Managerial New Revised Mgmt Svc - Confidential SECTION 1. POSITION INFORMATION a. Classification Title: Wildland Fire Suppression Specialist b. Classification No: 8255 c. Effective Date: 6/03/2019 d. Position No: e. Working Title: Firefighter f. Agency No: 49999 g. Section Title: Protection h. Employee Name: i. Work Location (City-County): John Day Grant County j. Supervisor Name (optional): k. Position: Permanent Seasonal Limited duration Academic Year Full Time Part Time Intermittent Job Share l. FLSA: Exempt If Exempt: Executive m. Eligible for Overtime: Yes Non-Exempt Professional No Administrative SECTION 2. PROGRAM AND POSITION INFORMATION a. Describe the program in which this position exists. Include program purpose, who’s affected, size, and scope. Include relationship to agency mission. This position exists within the Protection from Fire Program, which protects 1.6 million acres of Federal, State, county, municipal, and private lands in Grant, Harney, Morrow, Wheeler, and Gilliam Counties. Program objectives are to minimize fire damage and acres burned, commensurate with the 10-year average. Activities are coordinated with other agencies and industry to avoid duplication and waste of resources whenever possible. This position is directly responsible to the Wildland Fire Supervisor for helping to achieve District, Area, and Department-wide goals and objectives at the unit level of operation. b. Describe the primary purpose of this position, and how it functions within this program. -

Air Operations on the Fireline

Issue 21 • 2007 A Lessons Learned Newsletter Published Quarterly Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center Air Operations on the Fireline Lessons Learned Ten experienced interagency aviation personnel were recently interviewed regarding their most notable successes, difficult challenges, effective practices and pressing safety issues in wildland fire air operations. Special thanks are extended to these interagency community members for sharing their important lessons and practices with the wildland fire community. Notable Succ LCES from the Air Effective air tactical group supervisors (ATGS) employ the Lookouts/Communications/Escape Routes/Safety Zones (LCES) concept, in the same manner as ground firefighters; they just do so from an aerial platform. The ATGS can use LCES as a framework for communicating important safety information to ground per- In This Iue sonnel. Because the fire environment is constantly changing, an experienced Notable Successes ...........................1 ATGS will start out the operational period by contacting Division Supervisors, confirming their priorities, asking how they can help, and sharing feedback Difficult Challenges .......................... 3 regarding LCES and other pertinent tactical or logistical information. Aviation Effective Practices ............ 5 Building an Effective Air Operations Organization Pressing Safety Issues .................... 6 No one individual can claim a successful air operation, as it always takes a team of people who are dedicated to safety, communicate well, and help each How to Contact Us: other. In this environment, people need to work together to identify and quickly [email protected] resolve problems, proactively plan for emergencies and crisis response, and [email protected] help “fill the potholes of knowledge” by training and cross-training on various (520) 799-8760 or 8761 aircraft and procedures. -

CAL FIRE Fire and Emergency Response

CAL FIRE Fire and Emergency Response The CAL FIRE Mission The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection serves and safeguards the people and protects the property and resources of California. People to Meet the Challenge The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection is known for its extraordinary response to emergencies. The Department is always ready to respond regardless of the emergency - wildland fires; structure fires; automobile accidents; medical aids; swift water rescues; civil disturbances; lost hikers; hazardous material spills; train wrecks; floods; earthquakes; and even terrorist at- tacks. CAL FIRE’s firefighters, fire engines and aircraft respond to over 5,400 wildland fires that burn an average of over 156,000 acres each year; and answer the call over 450,000 times for other emergencies each year. Department personnel and equipment are a familiar sight throughout the state with responsibility for protecting over 31 million acres of California’s privately owned wildlands, as well as provide some type of emergency service under coop- erative agreements with 150, counties, cities & districts. The heart of CAL FIRE’s emergency response capability is a force of nearly 5,300 full-time fire professionals, foresters, and administrative employees; 1,783 seasonal firefighters; 2,750 lo- cal government volunteer firefighters; 600 Volunteers in Prevention; and 4,300 inmates and wards that currently provide 196 fire crews. Facilities Throughout the State The Department is divided into two regions with 21 administrative units statewide. Within these units, CAL FIRE operates 812 fire stations (237 state and 575 local government). CAL FIRE, in collaboration with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, is authorized to operate 39 conservation camps, and three training centers, located throughout the state. -

DFPC Aerial Firefighting Assets for 2021

DFPC Aerial Firefighting Assets for 2021 This document provides a summary of the Aerial Firefighting Assets owned or contracted by the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control (DFPC) in order to fulfill our mission to serve and safeguard the people and protect the property, resources, environment, and quality of life in Colorado. These aircraft are available to all state and local fire agencies within Colorado depending on availability. Aircraft information and approximate costs are listed below. Funds may be available to assist State and Local Agencies with State aircraft costs. Current Firefighting Aircraft Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) 2 - Pilatus PC-12 DFPC Owned. Available 365 days a year, no cost for initial response within Colorado. Centennial CO based. The Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) program was developed specifically to provide early detection of wildland fires and to support ongoing fires with decision-quality data that enhances firefighter safety and supports the effectiveness of other firefighting resources. The MMA are equipped with modern sensing, processing, and communication systems that allow for gathering and disseminating real-time wildfire and incident information. The MMA crew may be tasked to perform aerial supervision and provide assistance to Incident Commanders (IC) regarding fire behavior, weather monitoring, assisting crews with access, operational mapping, and communication links. These aircraft are authorized through a Cooperator Agreement to operate over all lands, regardless of jurisdiction Helicopters 2 - Bell 205++ - $1900 per flight hour DFPC Contracted. Available 120 (2021 increased to 230 days) consecutive days each May- October (2021 April thru November). One helicopter is based in each location of Montrose and Cañon City. -

NWCG Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed Fire, PMS 420-3

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group NWCG Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed Fire PMS 420-3 November 2020 NFES 001279 NWCG Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed Fire November 2020 PMS 420-3 NFES 001279 The NWCG Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed Fire contains information on prescribed fire smoke management techniques, air quality regulations, smoke monitoring, modeling, communication, public perception of prescribed fire and smoke, climate change, practical meteorological approaches, and smoke tools. The primary focus of this document is to serve as the textbook in support of NWCG’s RX- 410, Smoke Management Techniques course which is required for the position of Prescribed Fire Burn Boss Type 2 (RXB2). The Guide is useful to all who use prescribed fire, from private land owners to federal land managers, with practical tools, and underlying science. Many chapters are helpful for addressing air quality impacts from wildfires. It is intended to assist those who are following the guidance of the NWCG’s Interagency Prescribed Fire Planning and Implementation Procedures Guide, PMS 484, https://www.nwcg.gov/publications/484, in planning for, and addressing, smoke when conducting prescribed fires. For a glossary of relevant terminology, consult the NWCG Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology, PMS 205, https://www.nwcg.gov/glossary/a-z. For smoke management and air quality terms not commonly used by NWCG, consult the Smokepedia at https://www.frames.gov/smokepedia. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) provides national leadership to enable interoperable wildland fire operations among federal, state, tribal, territorial, and local partners. NWCG operations standards are interagency by design; they are developed with the intent of universal adoption by the member agencies. -

Aviation Operations and Resources Chapter 16

AVIATION OPERATIONS AND RESOURCES CHAPTER 16 1 Chapter 16 2 Aviation Operations and Resources 3 Purpose and Scope 4 Aviation resources are one of a number of tools available to accomplish fire 5 related land management objectives. 6 Aviation use must be prioritized based on management objectives and 7 probability of success. 8 The effect of aviation resources on a fire is directly proportional to the speed at 9 which the resource(s) can initially engage the fire, the effective capacity of the 10 aircraft, and the deployment of ground resources. 11 These factors are magnified by flexibility in prioritization, mobility, positioning, 12 and utilization of the versatility of many types of aircraft. 13 In addition to the priorities listed in the National Interagency Mobilization 14 Guide, Chapter 10 under headings “Total Mobility” and “Priorities”, 15 mobilization of aircraft should be based on optimizing the use of exclusive-use 16 contracted aircraft. Call-when-needed aircraft will be the last ordered and the 17 first released. The exception to this is use for initial action response and 18 capability. 19 Risk management is a necessary requirement for the use of any aviation 20 resource. The risk management process must include risk to ground resources, 21 and the risk of not performing the mission, as well as the risk to the aircrew. 22 Organizational Responsibilities 23 National Office – Department of Interior (DOI) 24 Office of Aviation Services (OAS) 25 The Office of Aviation Services (OAS) is responsible for the coordination of 26 aviation policy development and maintenance management within the agencies 27 of the Department of the Interior (DOI). -

4Th 170531 PPT FCP Updates

STAKEHOLDER ADVISORY FORUM 4 Jakarta || 31 May 2017 Stakeholder Advisory Forum for APP Forest Conservation Policy 2016 o Alternative peatland species program APP Forest o Hi-res LiDar Conservation Policy 2015 o 1st LiDar & retirement of critical peatland Implementation o IFFS launched o Strengthening fire monitoring and management system 2014 2013 o Peat expert team established o APP support landscape level 2012 forest conservation Vision 2020 o Forest Conservation Policy launched o Accelerated Zero Deforestation o Adoption of HCV, HCS and FPIC o Peat land Best Management Practice o APP Roadmap for Sustainability o Zero Deforestation Commitment phased approach POLICY COMMITMENT 1 NATURAL FOREST PROTECTION PROGRESS – INTEGRATED SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN ISFMP manuals for the FMUs completed. The new spatial plan for 38 FMUs are in process for approval from the Government. • 4 FMUs’ ISFMP spatial plans have been approved • Another 4 have been submitted for approval MOVING FORWARD Independent Observer (IO) program for ISFMP to be activated in 2017. It ensures independent 3rd party monitoring on ISFMPimplementation. The date for the first IO activity will be announced as soon as available. PROGRESS – 3 rd PARTY FOREST DEGRADATION Strengthen internal capacity for forest protection • Improve forest monitoring (land cover change and fire) • Improve forest fire management Engagement with community is critical in forest protection Community based forest security – TOR and related procedures have been developed. Next step is piloting: identify location and security partner PROGRESS – INTEGRATED FIRE MANAGEMENT Prevention: • IFFS/DMPA being implemented in all regions • ~70% Innovative fire prevention planning has been rolled out in the districts Preparation: • International training – better knowledge and understanding for all senior fire managers. -

3.13 Fire Protection Services and Wildfire Hazards

3.13 FIRE PROTECTION SERVICES AND WILDFIRE HAZARDS 3.13.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Services The project site is within the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s (CAL FIRE’s) Humboldt– Del Norte Unit (CAL FIRE 2018). The Humboldt–Del Norte Unit is located along the California coastline and includes Humboldt, Del Norte, and southwestern Trinity counties. The unit extends from the Oregon border in the north to Mendocino County in the south, and inland to the eastern boundary of Six Rivers National Forest. This area encompasses 3.1 million acres, of which 1,928,267 acres are state responsibility lands and 1,927,410 acres are direct protection area. Approximately 70 percent of these lands are managed for timber production and another 10 percent are recreation areas. The Humboldt–Del Norte Unit includes 1.3 million acres of federally managed and tribal lands (CAL FIRE 2018). The CAL FIRE Humboldt–Del Norte Unit is composed of one unit administration headquarters facility, 11 fire stations, three camps, one air attack base, and one helitack base, along with one state fire marshal office. The unit maintains 14 frontline engines, with three engines in reserve, two dozers, 15 inmate crews, one helicopter, one air attack, and one air tanker for fire suppression efforts. Approximately 100 permanent fire suppression personnel, 15 resource management personnel, and 10 clerical personnel staff these efforts. The Humboldt– Del Norte Unit also hires approximately 99 limited-term and seasonal personnel to supplement the permanent staff during fire season (CAL FIRE 2018). -

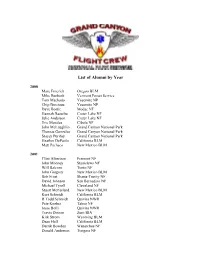

Helicopter Training Academy, List of Alumni by Year

List of Alumni by Year 2000 Mare Emerick Oregon BLM Mike Burbank Vermont Forest Service Tom Machado Yosemite NP Chip Brocious Yosemite NP Dave Bostic Modac NF Hannah Basarba Crater Lake NF Julie Anderson Crater Lake NF Eric Morales Cibola NF John McLaughlin Grand Canyon National Park Thomas Gonzales Grand Canyon National Park Stacey Purifoy Grand Canyon National Park Heather DePaolo California BLM Matt Pacheco New Mexico BLM 2001 Clint Albertson Fremont NF John Mooney Stanislaws NF Will Balcom Tonto NF John Gregory New Mexico BLM Bob Frost Shasta-Trinity NF David Johnson San Bernadino NF Michael Tyrell Cleveland NF Stuart McFarland New Mexico BLM Kurt Schmidt California BLM R Todd Schmidt Quivira NWR Pete Koeber Tahoe NF Jesse Bolli Quivira NWR Travis Dotson Zuni BIA Kirk Strom Wyoming BLM Dean Hall California BLM Derrik Bowden Wenatchee NF Donald Anderson Tongass NF Ladd Cotton Bitterroot NF 2002 Reid Flatten Wyoming BLM Mike Tyrrell Cleveland NF Jay Lusher Wyoming BLM Dave Martin North Dakota FWS Doug Wyatt Chugach NF Lonnie Forshee Huron NF Sam Stoker Coconino NF Trinette Davis Manti – LaSal NF Scott Amirault Grand Canyon National Park Ezequiel Rael Carson NF Kirk Warrington Chugach NF Pat Cook Chugach NF Phil Monsanto Lassen Volcanic NP 2003 Adam Stepanick Medicine Bow NF Mark Daniels Rocky Mountain NP Joe Suarez Cedar City IHC Matt Helan Montana BLM LaVerne Hermanson State Fire South Dakota Mike Wilke Grand Canyon National Park John Yurcik Grand Canyon National Park Hadley Kleeb Texas FWS Peter Pederson Wenatchee NF Althee Smith