Saulepi and Matsi Case Study Factors Influencing Satisfaction of Local Residents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sights Tõstamaa

SIGHTS of the Parish of TÕSTAMAA 2006 Contents Introduction ........................... 3 Lake of Tõhela ...............................22 Church of Tõhela ...........................23 Parish of Tõstamaa — brief Boulders of Alu ..............................23 historical survey ..................... 4 Viruna ...........................................24 Bog of Nätsi–Võlla .........................24 Sights of the Parish of Tõstamaa 4 Nature conservation area of Lindi .....4 How to behave in nature ........25 Lindi–Tõstamaa road ........................5 Staying in nature ............................26 Church of Pootsi–Kõpu ....................5 Roads and footpaths ......................26 Landscapes of cultural heritage .........6 Fishing and hunting .......................27 Manor of Pootsi ...............................7 Littering the nature .........................27 Lao and Munalaid ............................8 Everybody’s responsibility ...............28 Island of Manija aka Manilaid ............8 In brief ...........................................28 Kokkõkivi of Manija .........................9 Island of Sorgu ..............................10 Advice to hikers ....................29 Sacrificial tree of Päraküla ............... 11 Church of Seliste ............................ 11 Building ................................30 Pine tree of Tõrvanõmme ...............12 Hill of Levaroti ............................... 13 Village of Tõstamaa .......................14 Parish house of Tõstamaa .............. 15 Church of Tõstamaa ..................... -

62-2 Buss Sõiduplaan & Liini Marsruudi Kaart

62-2 buss sõiduplaan & liini kaart 62-2 Pärnu - Audru kool - Tõstamaa - Varbla - Vaata Veebilehe Režiimis Pivarootsi - Virtsu 62-2 buss liinil (Pärnu - Audru kool - Tõstamaa - Varbla - Pivarootsi - Virtsu) on 2 marsruuti. Tööpäeval on selle töötundideks: (1) Pärnu Bussijaam: 10:15 (2) Virtsu Sadam: 7:10 Kasuta Mooviti äppi, et leida lähim 62-2 buss peatus ning et saada teada, millal järgmine 62-2 buss saabub. Suund: Pärnu Bussijaam 62-2 buss sõiduplaan 62 peatust Pärnu Bussijaam marsruudi sõiduplaan: VAATA LIINI SÕIDUPLAANI esmaspäev Ei sõida teisipäev Ei sõida Virtsu Sadam 1 Tallinna Maantee, Estonia kolmapäev 10:15 Virtsu neljapäev Ei sõida Tallinna mnt, Estonia reede 10:15 Sillukse laupäev Ei sõida Hanila pühapäev Ei sõida Hanilaristi Rame 62-2 buss info Pivarootsi Suund: Pärnu Bussijaam Peatust: 62 Muriste Reisi kestus: 127 min Liini kokkuvõte: Virtsu Sadam, Virtsu, Sillukse, Hõbesalu Hanila, Hanilaristi, Rame, Pivarootsi, Muriste, Hõbesalu, Paatsalu, Vapri, Laine, Tamba, Surina, Nõmme, Varbla Kirik, Helmküla, Varbla, Raheste, Paatsalu Aruküla, Liivamäe, Õhu, Saulepi, Matsi Tee, Saare Sild, Vaiste, Seimani, Kastna, Ranniku, Leetsaare, Vapri Nurmiste, Nooruse, Tõstamaa, Tõstamaa Kool, Metsniku, Ermistu, Lepaspää, Harjase, Alu Tee, Laine Soomra, Roogoja, Kivimäe, Sanga-Tõnise, Kaelepa, Eassalu, Kihlepa, Kihlepa Tee, Põldeotsa, Uruste, Tamba Audru Kool, Rebasefarm, Kaske, Audru, Audru Viadukti, Lõvi, Valgeranna Tee, Papsaare, Ringraja, Surina Salme, Vana-Pärnu, Tallinna Maantee, Pärnu Bussijaam Nõmme Varbla Kirik Helmküla Varbla Raheste -

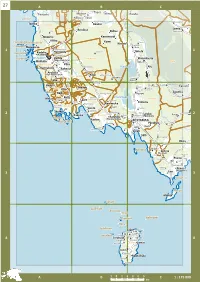

A 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 a B B C C 1 : 175

(Are as, *Lehtmetsa) Suigu Pivarootsi Paadrema Halinga ! Y " Kiviste ! Võrungi (Mõisaküla) Illuste ! Kõima ! Pivarootsi (Paatsalu as) Sookalda Ehala Oidrema Võrungi Illu ARE Are Y Pööravere! Y Y Kalli Nätsi Ahaste Vana-Lavassaare Enge-UduvereKännuküla 27 Vatla Vatla ! Ahaste Roodi Y Raidla 27 A Metsaküla Virtsu B C A Y B Elbu C Tori 28" Y ! YPärivere (as) ! Y Pansi ! ! ! Võrungi ! ! ! Täpsi LAVASSAARE Y Paatsalu Mõtsu Tiilima Palatu Koonga YLavassaare (k) Sõõrike-Parasmaa Kurena ! Pärivere Sooküla ! ! ! Võlla Y Oosäär Korju Tõusi Koonga Koonga Linnu Võrungi Jõõpre ! Ees-Soeva Y Tamba Y Ees-Soeva YMetsaküla ! Paatsalu Rauksi Ahaste Koonga ! Kodasmaa SoevaY Y !Saari Y ! Kirikuküla Lepplaane Virtsu Soeva ! Y Kodasmaa YRäägu-Mõisaküla Ännikse Y YKaseküla Kuiaru ! Viruna Taga-Soeva Ahaste Taga-Soeva Räägu YPiiu Mõtsu !Kidise Y Y ! Ahaste Räägu Tammiste (*Kadrina) ! ! ! ! (Riintali) Jõõpre Kanamardi (Riintali) ! Nõmme ! Y (Mõisaküla) Agasilla Metsaküla Y Ellamaa " Sauga Tori Ellamaa YRabaküla (Röövlaugu)Y Ahaste ! Y !Allika ! Räägu-Metsaküla !Koeri Teoste YPiiri Pöörilaid Piiukaarelaid Y ! Oara Kiraste ! Aruvälja Aruvälja Põhara !Ridalepa (Oti) ! Leelaste (Võlla as) (Võlla as) ! Orikalaid Mereäärse " (Läilaste) Y Tori krkms Y Vihaksi Y ! Taga-Helmküla Saunaküla ! 1 1 1 ! Kilksama 1 Helmküla Tammiste !Tõhela Nurme Kadaka Y YKõdu Raugilaid ! ! (Kalliste) YEes-Helmküla Audru Y Malda YSanga Jänesselja " ! Lõpejärv Varbla Ullaste (Seljaküla) Suura Kuralaid ! Paadrema !Männikuste " " Jänesselja (Vana-Varbla as) ! " !Liiva Lemmetsa ! Rütavere Mäliküla -

Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu Põhimääruse Kinnitamine

Väljaandja: Varbla Vallavolikogu Akti liik: määrus Teksti liik: algtekst Avaldamismärge: KO 1999, 14, 196 Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu põhimääruse kinnitamine Vastu võetud 28.05.1999 nr 23 Lähtudes kohaliku omavalitsuse korralduse seaduse (RT I 1993, 37, 558; 1994, 12,200; 19, 340; 72, 1263; 84,1475; 1995, 16, 228; 17, 237; 23, 334; 26--28, 355; 59, 1006; 97, 1664; 1996, 36, 738; 37, 739;40, 773; 48, 942;89, 1591; 1997, 13, 210; 29, 449 ja 450; 69, 1113; 1998, 28, 356; 59, 941; 61, 984; 1999, 10,155; 27, 392; 29, 401)paragrahvi 35 lõikest 2 ja rahvaraamatukogu seaduse (RT 1992, 17,250; RT I 1993, 41, 606; 79, 1180; 1996, 49,953; 1998, 103, 1696) paragrahvi 6 lõikest 1, Varbla Vallavolikogumäärab: 1. Kinnitada Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu põhimäärus(lisatud). Volikogu esimees MarikaSABIIN Lisa Varbla Vallavolikogu 28. mai 1999. amääruse nr 23juurde Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu põhimäärus Üldsätted 1. Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu (edaspidi raamatukogu) on VarblaVallavalitsuse haldusalas tegutsev Varbla vallaasutus. 2. Raamatukogu on üldkasutatav rahvaraamatukogu. 3. Raamatukogu kogud on koostiselt universaalsed, sisaldadesteeninduspiirkonna elanike põhivajadustele vastavaiderinevates keeltes, eri tüüpi ja laadi teavikuid. 4. Raamatukogu asub aadressil Helmküla küla, Varbla vald. 5. Raamatukogul on oma nimega pitsat. 6. Raamatukogul on õigus omada arvelduskontot. 7. Varbla Rahvaraamatukogu teeninduspiirkonda kuuluvad: Allika, Aruküla, Haapsi, Helmküla, Hõbesalu, Kadaka, Kanamardi,Kidise, Kilgi, Koeri, Korju, Kulli, Käru, Maade,Matsi, Mereäärse, Muriste, Mäliküla, Mõtsu, Nõmme,Paadrema, Paatsalu, Piha, Raespa, Raheste, Rannaküla,Rauksi, Rädi, Saare, Saulepi, Selja, Sookalda, Tamba, Tiilima, Täpsi, Tõusi,Vaiste, Varbla, Ännikse ja Õhu küla. 8. Raamatukogu põhimääruse ja selle muudatusedkinnitab Varbla Vallavolikogu. 9. Raamatukogu juhindub oma tegevuses Eesti Vabariigis kehtivatestõigusaktidest, sealhulgas rahvaraamatukoguseadusest, vallavolikogu määrustest ja otsustest ning vallavalitsusemäärustest ja korraldustest, samuti käesolevastpõhimäärusest. -

RANNIKKOVAELLUSREITTI LATVIA / VIRO 1200 Km 8

RANNIKKOVAELLUSREITTI LATVIA / VIRO 1200 km WWW.COASTALHIKING.EU 8 7 Estonia 6 5 2 4 Latvia 1 3 RETKI ITÄMEREN RANNALLA RANNIKKOVAELLUSREITTIÄ PITKIN Pituus noin 1200 km, Euroopan kaukovaellusreitin E9:n osa 8 etappia, voi valita minkä hyvänsä reitin etapin Kesto 60 päivää, keskimäärin 20 km vuorokaudessa REITTI LATVIASSA: Nida – Liepāja – Ventspils – Cape Kolka – Jūrmala – Rīga – Saulkrasti – Ainaži 1 DIŽJŪRA (ALKUMERI) 270 km päivät 1-15 2 MAZJŪRA (PIKKU MERI) 115 km päivät 16-20 3 JŪRMALA JA RIIKA 84 km päivät 21-24 4 VIDZEMEN RANNIKKO 112 km päivät 25-30 REITTI VIROSSA: Ikla – Pärnu – Virtsu – Lihula – Haapsalu – Paldiski – Tallinna 5 PÄRNU JA KALASTAJAKYLÄT 228 km päivät 31-41 6 MATSALUN KANSALLISPUISTO JA LÄNSI-VIRON SAARET 100 km päivät 42-46 7 HAAPSALU JA RANNAROOTSIN KYLÄT 136 km päivät 47-52 8 LOUNAIS-VIRON JYRKÄNNERANNIKKO JA PUTOUKSET 158 km päivät 53-60 Tietoa, retkiopas, kartat: WWW.COASTALHIKING.EU LATVIA DIŽJŪRA (ALKUMERI) ITÄMEREN KUURINMAAN RANNIKKO Nida – Kolka: 270 km, Päivä 1 – Päivä 15 Latvian Kuurinmaan Itämeren länsirannikkoa kutsutaan Dižjūraksi eli alkumereksi. Rannikon vaellusreitin alussa, Latvian ja Liettuan rajalta aina Kolkan niemelle, ranta on enimmäkseen hiekkainen. Alkumeren etappi on Latvian rannikon asumattomin osa. Kuitenkin siellä on Latvian kolmanneksi suurin kaupunki. Pāvilostan ja Sārnaten välissä on törmärannikkoa. Kylät ovat harvaanasuttuja, valtaosa asukkaista viettää siellä vain kesää. Slīteren kansallispuistossa reitti kulkee pitkin pelto- ja metsäteitä liiviläiskalastajakylien läpi. Mazirbessa ja Kolkassa paikalliset kalastajat käyvät edelleen merellä ja myyvät itsesavustettua kalaa. Alkumeren etappi päättyy Kolkan niemelle, joka erottaa Itämeren Riianlahdesta. ALKUMERESTÄ – „VIHREÄ SÄDE“ Silloin tällöin kesällä voi meren rannalla seurata auringonlaskun aikaan luonnonilmiötä, jota kutsutaan vihreäksi säteeksi. -

Tõstamaa Vaatamisväärsused

TÕSTAMAA VAATAMISVÄÄRSUSED 2006 Sisukord Sissejuhatus .............................. 3 Tõstamaa jõgi ............................ 22 Tõhela järv ................................ 22 Tõstamaa valla ajalooline lühiülevaade .............................. 4 Tõhela kirik ................................ 23 Alu kivikülv ............................... 23 Tõstamaa valla vaatamis- Viruna ....................................... 24 väärsused ................................... 4 Nätsi-Võlla raba ........................ 24 Lindi looduskaitseala ................... 4 Lindi-Tõstamaa tee ...................... 5 Käitumisest looduses ............. 25 Pootsi-Kõpu kirik ........................ 5 Looduses viibimine .................... 26 Pärandkultuurmaastikud ............. 6 Teed ja jalgrajad ......................... 26 Pootsi mõis ................................. 7 Kalastamine ja jaht .................... 27 Lao ja Munalaid ........................... 7 Looduse risustamine ................. 27 Manija saar ehk Manilaid ............. 8 Igaühe vastutus ......................... 28 Manija Kokkõkivi ......................... 9 Lühidalt ...................................... 28 Sorgu saar ................................. 10 Soovitused matkajale ............. 29 Päraküla ohvripuu ..................... 11 Seliste kirik ................................ 11 Ehitamine ................................ 30 Tõrvanõmme mänd ................... 12 Levaroti mägi ............................. 13 Tõstamaa alevik ......................... 14 Tõstamaa vallamaja .................. -

Sündmusturismi Arendamine Maapiirkonnas Varbla Valla Näitel

TARTU ÜLIKOOL Pärnu kolledž Turismiosakond Taivi Kaljura SÜNDMUSTURISMI ARENDAMINE MAAPIIRKONNAS VARBLA VALLA NÄITEL Lõputöö Juhendaja: PhD, Heli Tooman Pärnu 2014 SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ............................................................................................................. 3 1. Sündmusturismi teoreetilised käsitlused ............................................................ 6 1.1. Sündmusturismi areng ja suundumused ....................................................... 6 1.2. Sündmusturismi arendamine maapiirkonnas ............................................. 14 1.3. Maapiirkonna sündmuste külastajate reisimotiivid, ootused ja vajadused 16 2. Varbla valla sündmusturismi potentsiaali uuring ............................................. 20 2.1. Varbla valla turismi lühiülevaade............................................................... 20 2.2. Uuringu kirjeldus ........................................................................................ 23 2.3. Uuringu tulemused ja järeldused ................................................................ 25 3.Ettepanekud sündmusturismi arendamiseks Varbla vallas ................................ 37 Kokkuvõte ............................................................................................................. 43 Viidatud allikad ..................................................................................................... 46 Lisad ..................................................................................................................... -

Saulepi Rahvaraamatukogu Põhimääruse Kinnitamine

Väljaandja: Varbla Vallavolikogu Akti liik: määrus Teksti liik: algtekst Avaldamismärge: KO 1999, 14, 195 Saulepi Rahvaraamatukogu põhimääruse kinnitamine Vastu võetud 28.05.1999 nr 22 Lähtudes kohaliku omavalitsuse korralduse seaduse (RT I 1993, 37, 558; 1994, 12,200; 19, 340; 72, 1263; 84,1475; 1995, 16, 228; 17, 237; 23, 334; 26--28, 355; 59, 1006; 97, 1664; 1996, 36, 738; 37, 739;40, 773; 48, 942;89, 1591; 1997, 13, 210; 29, 449 ja 450; 69, 1113; 1998, 28, 356; 59, 941; 61, 984; 1999, 10,155; 27, 392; 29, 401)paragrahvi 35 lõikest 2 ja rahvaraamatukogu seaduse (RT 1992, 17,250; RT I 1993, 41, 606; 79, 1180; 1996, 49,953; 1998, 103, 1696) paragrahvi 6 lõikest 1, Varbla Vallavolikogumäärab: 1. Kinnitada Saulepi Rahvaraamatukogu põhimäärus(lisatud). Volikogu esimees MarikaSABIIN Lisa Varbla Vallavolikogu 28. mai 1999. amääruse nr 22juurde Saulepi Rahvaraamatukogu põhimäärus Üldsätted 1. Saulepi Rahvaraamatukogu (edaspidi raamatukogu) on VarblaVallavalitsuse haldusalas tegutsev Varbla vallaasutus. 2. Raamatukogu on üldkasutatav rahvaraamatukogu. 3. Raamatukogu kogud on koostiselt universaalsed, sisaldadesteeninduspiirkonna elanike põhivajadustele vastavaiderinevates keeltes, eri tüüpi ja laadi teavikuid. 4. Raamatukogu asub aadressil Kulli küla, Varbla vald. 5. Raamatukogul on oma nimega pitsat. 6. Raamatukogul on õigus omada arvelduskontot. 7. Saulepi rahvaraamatukogu teeninduspiirkonda kuuluvad: Allika, Aruküla, Haapsi, Helmküla, Hõbesalu, Kadaka, Kanamardi,Kidise, Kilgi, Koeri, Korju, Kulli, Käru, Maade,Matsi, Mereäärse, Muriste, Mäliküla, Mõtsu, Nõmme,Paadrema, Paatsalu, Piha, Raespa, Raheste, Rannaküla,Rauksi, Rädi, Saare, Saulepi, Selja, Sookalda, Tamba, Tiilima, Täpsi, Tõusi,Vaiste, Varbla, Ännikse ja Õhu küla. 8. Raamatukogu põhimääruse ja selle muudatusedkinnitab Varbla Vallavolikogu. 9. Raamatukogu juhindub oma tegevuses Eesti Vabariigis kehtivatestõigusaktidest, sealhulgas rahvaraamatukoguseadusest, vallavolikogu määrustest ja otsustest ning vallavalitsusemäärustest ja korraldustest, samuti käesolevastpõhimäärusest. -

Varbla Valla 2015.Aasta Majandusaasta Aruanne

Varbla valla 2015.aasta majandusaasta aruanne Nimetus Varbla Vallavalitsus Aadress Varbla küla Varbla vald Pärnumaa Telefon + 372 44 96 680 Faks + 372 44 96 691 E-posti aadress [email protected] Interneti kodulehekülje aadress www.varbla.ee Majandusaasta algus 01.01.2015 Majandusaasta lõpp 31.12.2015 Audiitor Allika Audiitor OÜ Varbla Vallavalitsus Majandusaasta aruanne 2015 Sisukord 1. Tegevusaruanne 1.1 Valla struktuur 3 1.2 Peamised finantsnäitajad 3 1.3 Ülevaade majanduskeskkonnast 5 1.4 Ülevaade valla arengukava täitmisest 6 2. Raamatupidamise aastaaruanne 10 2.1 Bilanss 10 2.2 Tulemiaruanne 11 2.3 Rahavoogude aruanne 12 2.4 Netovara muutuste aruanne 13 2.5 Eelarve täitmise aruanne 14 2.6 Raamatupidamise aastaaruande lisad 15 3. Allkiri majandusaasta aruandele 26 2 Varbla Vallavalitsus Majandusaasta aruanne 2015 TEGEVUSARUANNE Tegevusaruandes antakse ülevaade Varbla valla majandusaasta tegevusest ja asjaoludest, millel on määrav tähtsus Varbla valla finantsseisundi ja majandustegevuse hindamisel, olulistest sündmustest ning eeldatavatest arengusuundadest järgmisel majandusaastal. Varbla Vallavalitsuse struktuur: 1. Varbla Põhikool 2. Vallavalitsus 3. Hooldekodu 4. Varbla Lasteaed 5. Varbla Rahvamaja 6. Saulepi Seltsimaja 7. Paadrema Külakeskus 8. Varbla Raamatukogu 9. Saulepi Raamatukogu 10. Volikogu 11. Heakord 12. Kodune sotsiaalhooldus 13. Varbla kalmistu 14. Paadrema kalmistu Asutuste struktuuris ei ole aruandeaastal muutuseid toimunud. 1.septembrist 2016 liidetakse Varbla Lasteaed ja Varbla Põhikool üheks struktuuriüksuseks, -

62-1 Buss Sõiduplaan & Liini Marsruudi Kaart

62-1 buss sõiduplaan & liini kaart 62-1 Pärnu - Audru kool - Tõstamaa - Varbla - Lihula Vaata Veebilehe Režiimis 62-1 buss liinil (Pärnu - Audru kool - Tõstamaa - Varbla - Lihula) on 3 marsruuti. Tööpäeval on selle töötundideks: (1) Lihula: 7:10 (2) Pärnu Bussijaam: 10:20 (3) Varbla Kirik: 7:10 Kasuta Mooviti äppi, et leida lähim 62-1 buss peatus ning et saada teada, millal järgmine 62-1 buss saabub. Suund: Lihula 62-1 buss sõiduplaan 66 peatust Lihula marsruudi sõiduplaan: VAATA LIINI SÕIDUPLAANI esmaspäev 7:10 teisipäev 7:10 Pärnu Bussijaam 13 Pikk, Pärnu kolmapäev Ei sõida Tallinna Maantee neljapäev 7:10 3 Johann Voldemar Jannseni Tänav, Pärnu reede Ei sõida Vana-Pärnu laupäev Ei sõida 31 Haapsalu mnt, Pärnu pühapäev Ei sõida Salme Ringraja Pärnu — Lihula, Estonia 62-1 buss info Papsaare Suund: Lihula 1 Kukeseene Tee, Estonia Peatust: 66 Reisi kestus: 118 min Valgeranna Tee Liini kokkuvõte: Pärnu Bussijaam, Tallinna Maantee, Vana-Pärnu, Salme, Ringraja, Papsaare, Valgeranna Lõvi Tee, Lõvi, Audru Viadukti, Audru, Kaske, Rebasefarm, Audru Kool, Uruste, Põldeotsa, Kihlepa Tee, Kihlepa, Audru Viadukti Eassalu, Kaelepa, Sanga-Tõnise, Kivimäe, Roogoja, Soomra, Alu Tee, Harjase, Lepaspää, Ermistu, Audru Metsniku, Tõstamaa Kool, Tõstamaa, Nooruse, 1b Lihula Maantee, Audru Nurmiste, Leetsaare, Ranniku, Kastna, Seimani, Vaiste, Saare Sild, Matsi Tee, Saulepi, Õhu, Liivamäe, Kaske Aruküla, Raheste, Varbla, Helmküla, Varbla Kirik, 1 Kase Tänav, Audru Nõmme, Surina, Tamba, Laine, Vapri, Paatsalu, Vatla, Vatlamäe, Linnuse, Lõo, Karuse, Kotiristi, -

Lihula Gümnaasiumi Abiturientide Ballil Koguti Rasmuse Toetuseks Üle 8000 Euro

Lääneranna valla ajaleht / Nr 16 / Aprill 2019 LÄÄNERANNA TEATAJA / Nr 16 / APRILL 2019 1 Puhtus puhkes õitsema karulauk. Foto: Arno Peksar Lihula Gümnaasiumi abiturientide ballil koguti Rasmuse toetuseks üle 8000 euro Kanter. Tantsude vaheajal lahutas naasium, Lääneranna Vallavalitsus, osalejate meelt mustkunstnik Richard Massu Ratsaklubi, Matsalu Veevärk Samarüütel ning keha saadi kinnitada AS, Võilille Köök, Piljardiklubi Pool 8, sponsorite toel kaetud suupistelaua Viiking Spaa Hotell, Trientalis OÜ, ääres. Lihula Noortemaja, Lõpe Klubi, Green- cube OÜ. Seejärel vallutas lava üllatusesineja Foto: Eliise Lepp Foto: Katrin Veek Inger, kes kohe saali tantsima ning Täname õhtujuhte, esinejaid, Heategevusliku balli turundusjuht kaasa laulma pani. Kui Inger oli ka fotograafe ning ülejäänud abistajaid, oma kordusloo esitanud, asusid mikro- kes nõu ja jõuga peo toimumisele eljapäeval, 18. aprillil toimus fonide ette balli peakorraldajad Liisa kaasa aitasid ning oma aega panusta- N Greencube OÜ ruumides Raavel ja Svea Stahlman, kes andsid sid. Eelkõige soovime tänada neid ini- Lihula Gümnaasiumi koolinoorte Rasmuse isale üle tšeki, mille väär- mesi, kes andsid oma panuse Rasmuse heategevuslik ball, mille üks eesmärk tus tolleks hetkeks oli 7236,37 eurot. taastusravi kulude katmiseks. LisetFotod: Kuusik oli koguda raha 16-aastase Türi poisi Toomas Juhanson lausus: „Tahan taastusraviks. Tulemus ületas igasu- tänada kõiki! See läheb Rasmusele gused ootused, sest Rasmuse jaoks taastusraviks, mis võtab väga pikka koguti kokku üle 8000 euro. aega, kuid praeguste tulemustega võime rahul olla ning üht-teist lubada.” Abiturientide lõpuballi etteval- Kuivõrd balliks ettevalmistust kajas- mistused algasid veebruaris ja kulm- tas ETV saade „Ringvaade”, siis tänu ineerusid mõned minutid enne küla- meediakajastusele on toetussumma liste saabumist. Kogu Lihula peatänav tänaseks kasvanud juba üle 8000 euro. -

Rahvastiku Ühtlusarvutatud Sündmus- Ja Loendusstatistika

EESTI RAHVASTIKUSTATISTIKA POPULATION STATISTICS OF ESTONIA __________________________________________ RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Pärnumaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma Kaisma Vändra Pärnu-Jaagupi Vändra Tootsi Koonga Halinga Lavassaare Are Varbla Tori Audru Sauga Sindi Paikuse Tõstamaa PÄRNU Uulu Surju Saarde Kilingi-Nõmme Kihnu Tali Häädemeeste Tallinn 2005 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Pärnumaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma RU Sari C Nr 24 Tallinn 2005 © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre Kogumikku täiendab diskett Pärnumaa rahvastikuarengut kajastavate joonisfailidega, © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus. The issue is accompanied by the diskette with charts on demographic development of Pärnumaa population, © Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre. ISBN 9985-820-83-5 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE Postkast 3012, Tallinn 10504, Eesti Kogumikus esitatud arvandmed on elektrooniliselt Lotus- või ASCII-formaadis. Soovijail palun pöörduda Eesti Kõrgkoolidevahelise Demouuringute Keskuse poole. Data tables presented in the issue are available in Lotus or ASCII format from Estonian Interuniversity Population