College of Health Sciences School of Public Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Protecting Land Tenure Security of Women in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation Program

PROTECTING LAND TENURE SECURITY OF WOMEN IN ETHIOPIA: EVIDENCE FROM THE LAND INVESTMENT FOR TRANSFORMATION PROGRAM Workwoha Mekonen, Ziade Hailu, John Leckie, and Gladys Savolainen Land Investment for Transformation Programme (LIFT) (DAI Global) This research paper was created with funding and technical support of the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights, an initiative of Resource Equity. The Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights is a community of learning and practice that works to increase the quantity and strengthen the quality of research on interventions to advance women’s land and resource rights. Among other things, the Consortium commissions new research that promotes innovations in practice and addresses gaps in evidence on what works to improve women’s land rights. Learn more about the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights by visiting https://consortium.resourceequity.org/ This paper assesses the effectiveness of a specific land tenure intervention to improve the lives of women, by asking new questions of available project data sets. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to investigate threats to women’s land rights and explore the effectiveness of land certification interventions using evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation (LIFT) program in Ethiopia. More specifically, the study aims to provide evidence on the extent that LIFT contributed to women’s tenure security. The research used a mixed method approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative information was analyzed from the profiles of more than seven million parcels to understand how the program had incorporated gender interests into the Second Level Land Certification (SLLC) process. -

Next Stage for Dairy Development in Ethiopia

The NEXT STAGE IN DAIRY DEVELOPMENT FOR ETHIOPIA Dairy Value Chains, End Markets and Food Security Cooperative Agreement 663-A-00-05-00431-00 Submitted by Land O'Lakes, Inc. P.O. Box 3099 code 1250, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia November 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENT Pages ACRONYMNS…………………………………………………………………………………. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………………………... 6 1. OVERVIEW OF THE DAIRY SUB-SECTOR STUDY………………………………….10 1.1. The Role of the Dairy Sub-Sector in the Economy of Ethiopia 1.1.1. Milk Production and its Allocation 1.1.2 Livestock and Milk in the household economy 1.2. The Challenges 1.3. A Value Chain Approach 1.4. The Tasks and the Study Team 2. DEMAND FOR MILK AND MILK PRODUCTS…………………………………….…. 15 2.1. Milk Consumption 2.1.1. Milk and Milk Product Consumption in Urban Areas 2.1.2. Milk and Milk Product Consumption in Rural Areas 2.1.3. Milk and Milk Product Consumption in Pastoral Areas 2.2. Milk Consumption Compared to Other Countries 2.3. Milk’s Role for Food Security and Household Nutrition 2.4. Consumption of Imported Milk Products by Areas and Product Categories – domestic and imported 2.5. Milk Consumption in 2020 2.5.1.. High Estimate 2.5.2. Middle of the Range Estimate 2.5.3. Low Estimate 2.6. Assessment 3. DAIRY PRODUCTION……………………………………………………………..…… 30 3.1. Current Situation 3.2. Milk Production Areas (waiting on the maps) 3.3. Production systems and Milk Sheds (see zonal data in annex 3.3.1. Commercial Production 3.3.2. Peri-Urban and Urban Production 3.3.3. -

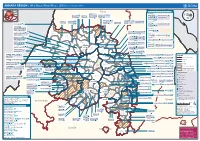

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Debre Berhan University College of Social Sciences & Humanities Department of Geography and Environmental Studies

DEBRE BERHAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND VARIABILITY ON RURAL LIVELIHOODS AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES: THE CASE OF MERHABETE WOREDA, NORTH SHEWA ZONE, AMHARA NATIONAL REGIONAL STATE, ETHIOPIA. By: Kefelegn Chernet July 2020 Debre Berhan, Ethiopia DEBRE BERHAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND VARIABILITY ON RURAL LIVELIHOODS AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES: THE CASE OF MERHABETE WOREDA, NORTH SHEWA ZONE, AMHARA NATIONAL REGIONAL STATE, ETHIOPIA. By Kefelegn Chernet A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies to Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of science in Environment and Sustainable Development. Advisor Dr. Arragaw Alemayehu Debre Berhan University Debre Berhan, Ethiopia July, 2020 DEBRE BERHAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES THESIS SUBMISSION FOR DEFENSE APPROVAL SHEET – I This is to certify that the thesis entitled: Impacts of climate change and variability on rural livelihoods and community responses: the case of Merhabete woreda, North shewa zone, Amhara national regional state, Ethiopia. submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science with specialization in Environment and sustainable development of the Graduate Program of the Geography and Environmental studies, College of Social Science and Humanities, Debre Berhan University and is a record of original research carried out by Kefelegn Chernet Id. No PGR 028/11, under my supervision, and no part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree or diploma. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

Final Country Report

Land Governance Assessment Framework Implementation in Ethiopia Public Disclosure Authorized Final Country Report Supported by the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared Zerfu Hailu (PhD) Public Disclosure Authorized With Contributions from Expert Investigators January, 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Extended executive summary .............................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 18 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 19 3. The Context ................................................................................................................................................... 22 3.1 Ethiopia's location, topography and climate ........................................................................................... 22 3.2 Ethiopia's settlement pattern .................................................................................................................... 23 3.3 System of Governance and legal frameworks ........................................................................................ -

Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Livestock Ailments in Ensaro District, North Shewa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia

Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used To Treat Livestock Ailments In Ensaro District, North Shewa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia Asaye Asfaw ( [email protected] ) Debre Brehan University Ermias Lulekal Addis Ababa University Tamrat Bekele Addis Ababa University Asfaw Debella Ethiopian Public Health Institute Eyob Debebe Ethiopian Public Health Institute Bihonegn Ssisay Ethiopian Public Health Institute Research Article Keywords: Ethiopia, Ethnoveterinary medicine, livestock diseases, indigenous knowledge Posted Date: August 17th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-733200/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/24 Abstract Introduction: In Ethiopia, the majority of animal owners throughout the country depend on traditional healthcare practices to manage their animals’ health. Ethnoveterinary practices play signicantly greater roles in livestock health care as an alternative or integral part of modern veterinary practices. This is because traditional medicines have remained the most economically affordable and easily available form of therapies for resource-poor communities. Even although, ethnoveterinary medicine is the most important and has higher acceptance and trust by the community in Ethiopia, ethnoveterinary medicinal plants and associated indigenous practices are not adequately documented. This study aimed to identify and document ethnoveterinary medicinal plants with their associated indigenous practices along with the habitats of these plants in Ensaro district. Methods: This ethnobotanical survey included 389 informants (283 males and 106 females) from all 14 kebeles of Ensaro district, which is the smallest administrative unit in Amhara Regional State's North Shewa Zone. Systematic random and intentional sampling techniques have been used to obtain representative informants. -

ETHIOPIA National Disaster Risk Management Commission National Flood Alert # 2 June 2019

ETHIOPIA National Disaster Risk Management Commission National Flood Alert # 2 June 2019 NATIONAL FLOOD ALERT INTRODUCTION NMA WEATHER OUTLOOK FOR kiremt 2019 This National Flood Alert # 2 covers the Western parts of the country, i.e. Benishangul Gumuz, Gambella, Western Amhara, Western Oromia, and Western highlands of SNNPR anticipated Kiremt season, i.e. June to September to receive normal rainfall tending to above normal rainfall. 2019. The National Flood Alert # 1 was issued in April 2019 based on the NMA Eastern and parts of Central Ethiopia, western Somali, and southern belg Weather Outlook. This updated Oromia are expected to receive dominantly normal rainfall. Flood Alert is issued based on the recent Afar, most of Amhara, Northern parts of Somali and Tigray are expected NMA kiremt Weather outlook to to experience normal to below normal rainfall during the season. highlight flood risk areas that are likely to receive above normal rainfall during Occasionally, heavy rainfalls are likely to cause flash and/or river floods the season and those that are prone to in low laying areas. river and flash floods. This flood Alert Tercile rainfall probability for kiremt season, 2019 aims to prompt early warning, preparedness, mitigation and response measures. Detailed preparedness, mitigation and response measures will be outlined in the National Flood Contingency Plan that will be prepared following this Alert. The National Flood Alert will be further updated as required based on NMA monthly forecast and the N.B. It is to be noted that the NMA also indicated 1993 as the best analogue year for 2019 situation on the ground. -

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Department of Earth Sciences

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES HYDROGEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF CHACHA CATCHMENT A VOLCANIC AQUIFER SYSTEM, CENTRAL ETHIOPIA A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Science in Hydrogeology BY: YONAS MULUGETA JUNE, 2009 ADDIS ABABA Hydrogeological Investigation of Chacha catchment, a volcanic aquifer system, central Ethiopia. ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES Hydrogeological investigation of Chacha Catchment a volcanic aquifer system, central Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to The School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University In partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Science in Hydrogeology BY: YONAS MULUGETA June, 2009 ADDIS ABABA 1 Hydrogeological Investigation of Chacha catchment, a volcanic aquifer system, central Ethiopia. DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that my thesis being entitled in my original work has not presented for a degree in any other university. Sources of relevant materials taken from books and articles have been duly acknowledged. Name: Yonas Mulugeta Signature: __________________ Date: ___________________ This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as University advisor Name: Dr. Tenalem Ayenew (advisor) Signature: __________________________ Date: _________________________ 2 Hydrogeological Investigation of Chacha catchment, a volcanic aquifer system, central Ethiopia. ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES HYDROGEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF CHACHA CATCHMENT A VOLCANIC AQUIFER SYSTEM, CENTRAL ETHIOPIA By YONAS MULUGETA Faculty of Natural Science Department of Earth Sciences Approval by board of examiners Dr. Balemwal Atnafu _________________________ (Chairman) Dr. Tenalem Ayenew _________________________ (Advisor) _________________________ (Examiner) _________________________ (Examiner) 3 Hydrogeological Investigation of Chacha catchment, a volcanic aquifer system, central Ethiopia. -

Full-Text (PDF)

Vol.10(8), pp. 158-164, August 2018 DOI: 10.5897/JAERD2018.0962 Articles Number: 460460257932 ISSN: 2141-2170 Copyright ©2018 Journal of Agricultural Extension and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JAERD Rural Development Full Length Research Paper Participatory on farm evaluation of improved mungbean technologies in the low land areas of North Shewa Zone Amhara Region, Ethiopia Yehuala Kassa*, Daneil Admasu, Abiro Tigabe, Amsalu Abie and Dejene Mamo Amhara Agricultural Research Institute Debre Birhan Research Center Ethiopia. Received 7 May, 2018; Accepted 25 June, 2018 The study was conducted in four selected potential areas of North Shewa zone namely; Kewot, Efratana gidim, Ensaro and Merhabete district. The main objective of the study was to evaluate, select the best performing mungbean varieties and to assess farmer’s technology preference. The experiment was done using three improved varieties namely; Rasa (N-26), NLV-1, and Arkebe improved varieties and local variety as a check. The analytical result showed that Rasa (N-26) variety was preferred by the farmers followed by NLV-1. The result gotten from the analysis of variance indicated that the difference among the means of the mungbean varieties for grain yield, pod length and hundred seed weight are significant at 5% probability level for both locations. The highest yield (1541.3 kg/ha) was recorded from Rasa (N-26) variety at Jema valley followed by the local variety (1243.3 kg/ha), while the lowest yield (735.7 and 676.3 kg/ha) was obtained from the varieties NLV-1 and Arkebe, respectively.