Competition and Intertidal Zonation of Barnacles at Leigh, New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Settlement and Succession on Rocky Shores at Auckland, North Island, New Zealand

ISSN 0083-7903, 70 (Print) ISSN 2538-1016; 70 (Online) Settlement and Succession on Rocky Shores at Auckland, North Island, New Zealand by PENELOPE A. LUCKENS New Zealand Oceanographic.Institute Memoir No. 70 1976 NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH Settlement and Succession on Rocky Shores at Auckland, North Island, New Zealand by PENELOPE A. LUCKENS New Zealand Oceanographic Institute, Wellington New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir No. 70 1976 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Citation according to World List of Scientific Periodicals ( 4th edn.): Mem. N.Z. oceanogr. Inst. 70 New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir No. 70 ISSN 0083-7903 Edited by Q. W. Ruscoe and D. J. Zwartz, Science Information Division, DSIR Received for publication May 1969 © Crown Copyright 1976 A. R. SHEARER, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND - 1976 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ CONTENTS Abstract page 5 Introduction .. 5 The experimental areas Location and physical structure Tidal phenomena 9 Terminology 9 General zonation pattern at the localities sampled 9 Methods 11 Settlement seasons 12 Organisms settling in the experimental areas (Table 1) 15 Factors affecting settlement of some of the organisms 42 Changes observed after clearance of the experimental areas .. 44 Temporal succession .. 60 Climax populations 60 Summary 61 Acknowledgments 61 Appendix 62 References 63 Index 64 3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. -

Assessing the Relationship Between Propagule Pressure and Invasion Risk in Ballast Water

ASSESSING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROPAGULE PRESSURE AND INVASION RISK IN BALLAST WATER Committee on Assessing Numeric Limits for Living Organisms in Ballast Water Water Science and Technology Board Division on Earth and Life Studies THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu PREPUBLICATION COPY THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the panel responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Support for this study was provided by the EPA under contract no. EP-C-09-003, TO#11. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number X-XXX-XXXXX-X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number XX-XXXXX Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 5th Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. PREPUBLICATION COPY The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare. -

Elminius Modestus Global Invasive

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Elminius modestus Elminius modestus System: Marine_terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Arthropoda Maxillopoda Sessilia Balanidae Common name Australian barnacle (English), New Zealand barnacle (English), Firepladet rur (Danish), Nieuw-Zeelandse zeepok (Dutch), Australseepocke (German), Sterretje (Dutch), Australische Seepocke (German), Kruisridderpok (Dutch) Synonym Austrominius modestus Similar species Summary Elminius modestus has spread successfully throughout the Western Europe coastal areas, since its introduction to the southeast coast of the Uk most probably on the hull of ships from New Zealand and /or Australia between 1940 and 1943. There are several factors that aid Elminius success as an invader. Elminius larval stages are eurythermal and euryhaline, enabling them to survive in a wide range of habitat types. E. modestus is a highly fecund species and has a short generation time. It is highly tolerant of changes in tempertaure and salinity. E. modestus compete with native barnacle species for space. It has been observed that the successful range expansion of the barnacle could be facilitated by a changing climate with warmer seas and tempertaures. view this species on IUCN Red List General Impacts Elminius modestus competes for space with the native barnacle Balanus balanoides along the coasts of Western Europe where it has spread widely (Crisp & Chipperfield 1948; Crisp 1958; Nehring, 2005; Barnes & Barnes 1960). Witte et al (2010) report that Austrominius modestus (=Elminius modestus) which was first reported on the Island of Sylt (North Sea) in 1955 and remained rare, has overtaken native barnacles Semibalanus balanoides and Balanus crenatus in abundance when surveyed in the summer of 2007. The authors suggest that this exponential increase in population numbers could be due to mild winters and warm summers over a period.\n Pathway Crisp (1958) noted two types of dispersal natural or 'marginal' dispersal at an average of 20-30 kms per year and long distance or 'remote' dispersal on the hull of a boat or ship. -

Testing Adaptive Hypotheses on the Evolution of Larval Life History in Acorn and Stalked Barnacles

Received: 10 May 2019 | Revised: 10 August 2019 | Accepted: 19 August 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5645 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Testing adaptive hypotheses on the evolution of larval life history in acorn and stalked barnacles Christine Ewers‐Saucedo1 | Paula Pappalardo2 1Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA Abstract 2Odum School of Ecology, University of Despite strong selective pressure to optimize larval life history in marine environ‐ Georgia, Athens, GA, USA ments, there is a wide diversity with regard to developmental mode, size, and time Correspondence larvae spend in the plankton. In the present study, we assessed if adaptive hypoth‐ Christine Ewers‐Saucedo, Zoological eses explain the distribution of the larval life history of thoracican barnacles within a Museum of the Christian‐Albrechts University Kiel, Hegewischstrasse 3, 24105 strict phylogenetic framework. We collected environmental and larval trait data for Kiel, Germany. 170 species from the literature, and utilized a complete thoracican synthesis tree to Email: ewers‐[email protected]‐kiel. de account for phylogenetic nonindependence. In accordance with Thorson's rule, the fraction of species with planktonic‐feeding larvae declined with water depth and in‐ creased with water temperature, while the fraction of brooding species exhibited the reverse pattern. Species with planktonic‐nonfeeding larvae were overall rare, follow‐ ing no apparent trend. In agreement with the “size advantage” hypothesis proposed by Strathmann in 1977, egg and larval size were closely correlated. Settlement‐com‐ petent cypris larvae were larger in cold water, indicative of advantages for large ju‐ veniles when growth is slowed. Planktonic larval duration, on the other hand, was uncorrelated to environmental variables. -

The Sensory Basis for Ecological Paradigms on Wave-Swept Shores

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Sensory Basis for Ecological Paradigms on Wave-Swept Shores A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Graham Andrew Ferrier 2010 UMI Number: 3452132 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI' Dissertation Publishing UMI 3452132 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 © copyright by Graham Andrew Ferrier 2010 The dissertation of Graham Andrew Ferrier is approved. ~~) V <L K x Paul Barber hfr-i~^/cz\ (hy^^ Steven D. Gaines OAjjut^ (juxs^-l^-s Cheryl Ann Zimmer, Committee Co-chair ^n^\; Richard K. Zimmer, Committee Co-chair University of California, Los Angeles 2010 DEDICATION To Carrie, Nayla, Mom, and Dad, for your unwavering support and belief in me for all these years, it has been a long time. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figure v List of Tables vii Acknowledgments viii Vita xi Abstract xiii Chapter 1 Whelk-Barnacle Interactions, the Energetics of Prey Choice, and the Sensory Basis for an Ecological Paradigm 1 Literature Cited 63 Chapter 2 -

Does Climatic Warming Explain Why an Introduced Barnacle Finally Takes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Publication Information Center Biol Invasions (2010) 12:3579–3589 DOI 10.1007/s10530-010-9752-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Does climatic warming explain why an introduced barnacle finally takes over after a lag of more than 50 years? Sophia Witte • Christian Buschbaum • Justus E. E. van Beusekom • Karsten Reise Received: 3 June 2009 / Accepted: 29 March 2010 / Published online: 21 April 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract Invading alien species may have to await and several warm summers in a row has led to an appropriate conditions before developing from a rare exponential population growth in A. modestus. addition to the recipient community to a dominance over native species. Such a retarded invasion seems Keywords Alien species Á Austrominius modestus Á to have happened with the antipodean cirripede Invasion Á Climate change Á North Sea crustacean Austrominius modestus Darwin, formerly known as Elminius modestus, at its northern range in Europe due to climatic change. This barnacle was introduced to southern Britain almost seven decades ago, and from there spread north and south. At the Introduction island of Sylt in the North Sea, the first A. modestus were observed already in 1955 but this alien Translocation of species across natural barriers by remained rare until recently, when in summer of human carriers has become a process of increasing 2007 it had overtaken the native barnacles Semibal- global importance in aquatic coastal ecosystems anus balanoides and Balanus crenatus in abundance. (Carlton 1985; Grosholz 2002). -

Darwin. a Reader's Guide

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES No. 155 February 12, 2009 DARWIN A READER’S GUIDE Michael T. Ghiselin DARWIN: A READER’S GUIDE Michael T. Ghiselin California Academy of Sciences California Academy of Sciences San Francisco, California, USA 2009 SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Alan E. Leviton, Ph.D., Editor Hallie Brignall, M.A., Managing Editor Gary C. Williams, Ph.D., Associate Editor Michael T. Ghiselin, Ph.D., Associate Editor Michele L. Aldrich, Ph.D., Consulting Editor Copyright © 2009 by the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISSN 0068-5461 Printed in the United States of America Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Table of Contents Preface and acknowledgments . .5 Introduction . .7 Darwin’s Life and Works . .9 Journal of Researches (1839) . .11 Geological Observations on South America (1846) . .13 The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842) . .14 Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands…. (1844) . .14 A Monograph on the Sub-Class Cirripedia, With Figures of All the Species…. (1852-1855) . .15 On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859) . .16 On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing (1863) . .23 The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877) . -

A Synopsis of the Literature on the Turtle Barnacles (Cirripedia: Balanomorpha: Coronuloidea) 1758-2007

EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 1 (ERC-SP1) A SYNOPSIS OF THE LITERATURE ON THE TURTLE BARNACLES (CIRRIPEDIA: BALANOMORPHA: CORONULOIDEA) 1758-2007 COMPILED BY: THE EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE ©2007 CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE ARNOLD ROSS (founder)† GEORGE H. BALAZS Scripps Institution of Oceanography NOAA, NMFS Marine Biology Research Division Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center LaJolla, California 92093-0202 USA 2570 Dole Street †deceased Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 USA [email protected] MICHAEL G. FRICK Assistant Director/Research Coordinator THEODORA PINOU Caretta Research Project Assistant Professor 9 Sandy Creek Court Secondary Science Education Savannah, Georgia 31406 USA Coordinator [email protected] Department of Biological & 912 308-8072 Environmental Sciences Western Connecticut State University JOHN D. ZARDUS 181 White Street Assistant Professor Danbury, Connecticut 06810 USA The Citadel [email protected] Department of Biology 203 837-8793 171 Moultrie Street Charleston, South Carolina 29407 USA ERIC A. LAZO-WASEM [email protected] Division of Invertebrate Zoology 843 953-7511 Peabody Museum of Natural History Yale University JOSEPH B. PFALLER P.O. Box 208118 Florida State University New Haven, Connecticut 06520 USA Department of Biological Sciences [email protected] Conradi Building Tallahassee, Florida 32306 USA CHRIS LENER [email protected] Lower School Science Specialist 850 644-6214 Wooster School 91 Miry Brook Road LUCIANA ALONSO Danbury, Connecticut 06810 USA Universidad de Buenos Aires/Karumbé [email protected] H. Quintana 3502 203 830-3996 Olivos, Buenos Aires 1636 Argentina [email protected] KRISTINA L. WILLIAMS 0054-11-4790-1113 Director Caretta Research Project P.O. -

Oceanography and Marine Biology an Annual Review Volume 58

Oceanography and Marine Biology An Annual Review Volume 58 Edited by S. J. Hawkins, A. L. Allcock, A. E. Bates, A. J. Evans, L. B. Firth, C. D. McQuaid, B. D. Russell, I. P. Smith, S. E. Swearer, P. A. Todd First edition published 2021 ISBN: 978-0-367-36794-7 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-35149-5 (ebk) Chapter 1 The Biology of Austrominius Modestus (Darwin) in its Native and Invasive Range Ruth M. O’Riordan, Sarah C. Culloty, Rob Mcallen & Mary Catherine Gallagher (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by University College Cork Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 2020, 58, 1–78 © S. J. Hawkins, A. L. Allcock, A. E. Bates, A. J. Evans, L. B. Firth, C. D. McQuaid, B. D. Russell, I. P. Smith, S. E. Swearer, P. A. Todd, Editors Taylor & Francis THE BIOLOGY OF AUSTROMINIUS MODESTUS (DARWIN) IN ITS NATIVE AND INVASIVE RANGE RUTH M. O’RIORDAN, SARAH C. CULLOTY, ROB MCALLEN & MARY CATHERINE GALLAGHER School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences and the Environmental Research Institute, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland Abstract Austrominius modestus, formerly Elminius modestus, is a relatively small species of four-plated acorn barnacle, which is native to the subtropical and temperate zones of Australasia. It was introduced into Europe in the 1940s, where its current range includes England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland and continental Europe from Denmark to southern Portugal, as well as two reported locations in the Mediterranean Sea. This species occurs intertidally and subtidally on a very wide range of substrata in both its native and introduced range and is found on sheltered to intermediate exposed shores, but is absent from wave-exposed shores, probably due to the relative fragility of its shell. -

Rahui and Marine Construction: Potential for Enhancement of Taonga Species

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Rahui And Marine Construction: Potential For Enhancement of Taonga species A thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Major in Biological Science By Danielle Fox Hamilton, New Zealand. February 2010 Abstract The aims of my study were to investigate whether marine reserves enhance intertidal species used by Māori in a traditional or contemporary sense, and whether artificial structures in the intertidal region (such as wharf and bridge pilings) provide suitable habitats for traditionally harvested species. Further, I investigated whether non-indigenous species were found in these habitats, which may affect traditionally used species. The abundance of ataata (cat‟s eyes; Turbo smaragdus) and kina (sea urchin; Evechinus chloroticus) were quantified in three marine protected areas and nearby unprotected reference beaches. -

04 Hoeg Proof Final Version Web.Indd

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny Jahr/Year: 2009 Band/Volume: 67 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hoeg J.T., Pérez- Losada Marcos, Glenner Henrik, Kolbasov Gregory A., Crandall Keith A. Artikel/Article: Evolution of Morphology, Ontogeny and Life Cycles within the Crustacea Thecostraca 199-217 Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 199 67 (2) 199 – 217 © Museum für Tierkunde Dresden, eISSN 1864-8312, 25.8.2009 Evolution of Morphology, Ontogeny and Life Cycles within the Crustacea Thecostraca JENS T. HØEG 1 *, MARCOS PÉREZ-LOSADA 2, HENRIK GLENNER 3, GREGORY A. KOLBASOV 4 & KEITH A. CRANDALL 5 1 Comparative Zoology, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark [[email protected]] 2 CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal 3 Marine Organismal Biology, Department of Biology, University of Bergen, Box 7803, 5020 Bergen, Norway 4 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, White Sea Biological Station, Biological Faculty, Moscow State University, Moscow 119899, Russia 5 Department of Biology & Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 84602-5181, USA * Corresponding author Received 16.iii.2009, accepted 8.vi.2009. Published online at www.arthropod-systematics.de on 25.viii.2009. > Abstract We use a previously published phylogenetic analysis of the Thecostraca to trace character evolution in the major lineages of the taxon. The phylogeny was based on both molecular (6,244 sites from 18S rna, 28S rna and H3 genes) and 41 larval morphological characters with broad taxon sampling across the Facetotecta (7 spp.), Ascothoracida (5 spp.), and Cirripedia (3 acrothoracican, 25 rhizocephalan and 39 thoracican spp.). -

PHYLUM ARTHROPODA: Subphylum Crustacea: Class Maxillipoda

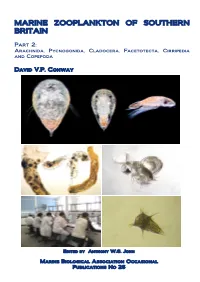

MARINE ZOOPLANKTON OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN Part 2: Arachnida, Pycnogonida, Cladocera, Facetotecta, Cirripedia and Copepoda David V.P. Conway Edited by Anthony W.G. John Marine Biological Association Occasional Publications0 No 26 1 MARINE ZOOPLANKTON OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN Part 2: Arachnida, Pycnogonida, Cladocera, Facetotecta, Cirripedia and Copepoda David V.P. Conway Marine Biological Association, Plymouth, UK Edited by Anthony W.G. John Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom Occasional Publications No 26 Front cover from top, left to right: Two types of facetotectan nauplii and a cyprid stage from Plymouth (Image: R. Kirby); Larval turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) faeces containing skeletons of the copepod Pseudocalanus elongatus, their undigested eggs and lipid droplets; The cladoceran Podon intermedius; Zooplankton identification course in MBA Resource Centre; Nauplius stage of parasitic barnacle, Peltogaster paguri. 2 Citation Conway, D.V.P. (2012). Marine zooplankton of southern Britain. Part 2: Arachnida, Pycnogonida, Cladocera, Facetotecta, Cirripedia and Copepoda (ed. A.W.G. John). Occasional Publications. Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, No 26 Plymouth, United Kingdom 163 pp. Electronic copies This guide is available for free download, from the National Marine Biological Library website - http://www.mba.ac.uk/NMBL/ from the “Download Occasional Publications of the MBA” section. © 2012 by the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. No part of this publication should be reproduced in any form without consulting the author. ISSN 02602784 This publication has been prepared as accurately as possible, but suggestions or corrections that could be included in any revisions would be gratefully received. [email protected] 3 Preface The range of zooplankton species included in this series of three guides is based on those that have been recorded in the Plymouth Marine Fauna (PMF; Marine Biological Association.