9781441967237.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pupillary Disorders LAURA J

13 Pupillary Disorders LAURA J. BALCER Pupillary disorders usually fall into one of three major cat- cortex generally do not affect pupillary size or reactivity. egories: (1) abnormally shaped pupils, (2) abnormal pupillary Efferent parasympathetic fibers, arising from the Edinger– reaction to light, or (3) unequally sized pupils (anisocoria). Westphal nucleus, exit the midbrain within the third nerve Occasionally pupillary abnormalities are isolated findings, (efferent arc). Within the subarachnoid portion of the third but in many cases they are manifestations of more serious nerve, pupillary fibers tend to run on the external surface, intracranial pathology. making them more vulnerable to compression or infiltration The pupillary examination is discussed in detail in and less susceptible to vascular insult. Within the anterior Chapter 2. Pupillary neuroanatomy and physiology are cavernous sinus, the third nerve divides into two portions. reviewed here, and then the various pupillary disorders, The pupillary fibers follow the inferior division into the orbit, grouped roughly into one of the three listed categories, are where they then synapse at the ciliary ganglion, which lies discussed. in the posterior part of the orbit between the optic nerve and lateral rectus muscle (Fig. 13.3). The ciliary ganglion issues postganglionic cholinergic short ciliary nerves, which Neuroanatomy and Physiology initially travel to the globe with the nerve to the inferior oblique muscle, then between the sclera and choroid, to The major functions of the pupil are to vary the quantity of innervate the ciliary body and iris sphincter muscle. Fibers light reaching the retina, to minimize the spherical aberra- to the ciliary body outnumber those to the iris sphincter tions of the peripheral cornea and lens, and to increase the muscle by 30 : 1. -

Taking the Mystery out of Abnormal Pupils

Taking the mystery out of abnormal pupils No financial disclosures Course Title: Taking the mystery out [email protected] of abnormal pupils Lecturer: Brad Sutton, OD, FAAO Clinical Professor IU School of Optometry . •Review of Anatomy Iris anatomy Iris sphincter Iris dilator Parasympathetic pathway Sympathetic pathway Parasympathetic Pathway Parasympathetic Pathway Light stimulates the retina then impulse Four neuron arc travels with the ganglion cells through the Retina to the pretectal nucleus in the chiasm into the optic tracts. 80% go to the midbrain (1) LGN , 20% to the pretectal nuclei.They Pretectal nucleus to the EW nucleus (2) then hemidecussate and terminate at the EW nucleus EW nucleus to the ciliary ganglion (3) Ciliary ganglion to the iris sphincter with short ciliary nerves (4) 1 Points of Interest Sympathetic Pathway Within the second order neuron there are Three neuron arc 30 near response fibers for every light Posterior hypothalamus to ciliospinal response fiber. This allows for light - near center of Budge ( C8 - T2 ). (1) dissociation. Center of Budge to the superior cervical The third order neuron runs with cranial ganglion in the neck (2) nerve III from the brain stem to the ciliary Superior cervical ganglion to the dilator ganglion. Superficially located prior to the muscle (3) cavernous sinus. Points of Interest Second order neuron runs along the surface of the lung, can be affected by a Pancoast tumor Third order neuron runs with the carotid artery then with the ophthalmic division of cranial nerve V 2 APD Testing testing……………….AKA……… … APD / reverse APD Direct and consensual response Which is the abnormal pupil ? Very simple rule. -

Complete and Incomplete Forms of the Benign Disorder Characterised By

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.16.8.449 on 1 August 1932. Downloaded from THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMOLOGY AUGUST, 1932 COMMUNICATIONS COMPLETE AND INCOMPLETE FORMS OF THE BENIGN DISORDER CHARACTERISED BY TONIC PUPILS AND ABSENT copyright. TENDON REFLEXES BY W. J. ADIE, M.D., F.R.C.P. PHYSICIAN, CHARING CROSS HOSPITAL AND ROYAL LONDON OPHTHALMIC HOSPITAL. OUT-PATIENT PHYSICIAN, THE NATIONAL HOSPITAL FOR NERVOUS DISEASES, QUEEN SQUARE http://bjo.bmj.com/ IN earlier papers on this subject it has been suggested that certain apparently dissimilar abnormal pupillary reactions formerly described as occurring in unrelated conditions are manifestations of the same disorder. The abnormal reactions are, on the one hand, the tonic pupillary reaction (syn. pupillotonia, myotonic reaction, tonic convergence reaction of pupils apparently inactive to light, on September 30, 2021 by guest. Protected Marcus's peculiar pupil phenomenon, non-luetic Argyll Robertson pupil, pseudo-Argyll Robertson pupil) and, on the other hand what may be called atypical phases of the tonic pupil. In the atypical phases tonic reactions are absent or difficult to detect and the state of the pupil in cases that present them is usually desig- nated by the term fixed pupil, ophthalmoplegia interna, iridoplegia or partial iridoplegia, of unknown origin. The disorder referred to, if the views expressed here are correct, may manifest itself in the following clinical forms: A. The complete form characterized by the presence in one or both eyes of the tonic convergence reaction in a pupil apparently Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.16.8.449 on 1 August 1932. -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

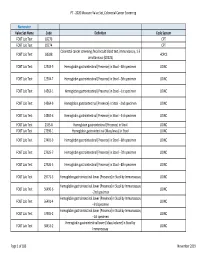

2020 Measure Value Set Colorectal Cancer Screening

PT ‐ 2020 Measure Value Set_Colorectal Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System FOBT Lab Test 82270 CPT FOBT Lab Test 82274 CPT Colorectal cancer screening; fecal occult blood test, immunoassay, 1‐3 FOBT Lab Test G0328 HCPCS simultaneous (G0328) FOBT Lab Test 12503‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐4th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 12504‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐5th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14563‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐1st specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14564‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐2nd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14565‐6 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐3rd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 2335‐8 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27396‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Mass/mass] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27401‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐6th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27925‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐7th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27926‐5 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐8th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 29771‐3 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay LOINC Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56490‐6 LOINC ‐‐2nd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56491‐4 LOINC ‐‐3rd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 57905‐2 -

Physical Therapy Practice

Physical Therapy Practice THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHOPAEDIC SECTION, APTA VOL. 18, NO. 2 2006 ORTHOPAEDIC CARDON REHABILITATION PRODUCTS, INC.™ Wurlitzer Industrial Park, 908 Niagara Falls Blvd. North Tonawanda, NY 14120 Telephone: 1-800-944-7868 • Fax: 716-297-0411 E-mail: [email protected] THE ACCEPTED STANDARD OF PERFORMANCE The Cardon Mobilization Table . Going beyond the third dimension . Now available with the patented option which eliminates the use of flexion and rotation levers. This allows the therapist to perform advanced manual therapy techniques with complete confidence and comfort with an ergonomically friendly design. The unique design provides more efficient and smooth setup while providing superior patient comfort. The option enhances patient care by allowing unsurpassed opportunity for more preciseness of treatment and monitoring of segments and joints. he design and concepts make this “T the best mobilization table manufactured today.” Professor Freddy Kaltenborn Autho, Int’l Lecturer in Manual Therapy he various sections have minimum flex “T allowing very accurate application of specific manual therapy techniques.” Olaf Evjenth ES! I would like to preview the Author, Int’l Lecturer in Manual Therapy Y Cardon Mobilization Table. Please rush your 15 minute VHS video (for standard model): SEE FOR Name: Title: YOURSELF Clinic/Institution: THESE Address: OUTSTANDING City: State: Zip Code: Telephone: Signature: FEATURES: CARDON REHABILITATION PRODUCTS, INC.™ • Accurate localization of the vertebral segment Wurlitzer Industrial Park, 908 Niagara Falls Blvd. • Precision and versatility of technique North Tonawanda, NY 14120 • Absolute control of the mobilization forces Telephone: 1-800-944-7868 • Fax: 716-297-0411 • Excellent stability for manipulation. E-mail: [email protected] Orthopaedic Practice Vol. -

Neurological History and Physical Examination

emedicine.medscape.com eMedicine Specialties > Clinical Procedures > none Neurological History and Physical Examination Kalarickal J Oommen, MD, FAAN, Professor and Crofoot Chair of Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Chief, Section of Epilepsy, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center; Medical Director, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) Covenant Comprehensive Epilepsy Center Updated: Nov 25, 2009 Neurological History "From the brain and the brain only arise our pleasures, joys, laughter and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, griefs, and tears.... These things we suffer all come from the brain, when it is not healthy, but becomes abnormally hot, cold, moist or dry." —Hippocrates The Sacred Disease, Section XVII Taking the patient's history is traditionally the first step in virtually every clinical encounter. A thorough neurologic history allows the clinician to define the patient's problem and, along with the result of physical examination, assists in formulating an etiologic and/or pathologic diagnosis in most cases.[1 ] Solid knowledge of the basic principles of the various disease processes is essential for obtaining a good history. As Goethe stated, "The eyes see what the mind knows." To this end, the reader is referred to the literature about the natural history of diseases. The purpose of this article is to highlight the process of the examination rather than to provide details about the clinical and pathologic features of specific diseases. The history of the presenting illness or chief complaint should -

Movement Disorders and Gait Disturbances

Movement disorders and gait disturbances Kovács Norbert PTE ÁOK Neurológiai Klinika Pécs 1 MD pathophysiology z Genetic mutation or environmental injury of basal ganglia functioning z Pallidum, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, caudate nucleus, pedunculopintine nucleus 2 Vitek JL. Mov Disord 2002;17(Supp 3):S49-62 Phenomenology in MD Hyperkinetic Isokinetic Hypokinetic • Tremor (regular) • Ataxia • Rigidity • Chorea • Bradykinesia • Ballism • Hypokinesia • Dystonia • Athetosis • Myoclonus (jerky) • Tic (jerky) 3 Hyperkinetic movements 4 Tremor classification More or less regular, sinusoid movements Any body parts can be affected (e.g. limbs, neck, trunc, vocal cords) Classification: • Intensity (invisible, barely visible, moderate, severe) • Frequency (slow or fast) • Position – Rest tremor (e.g. Parkinsonism) – Postural tremor (e.g. hyperthyroidism) – Kinetic tremor (e.g. essential tremor) – Intention tremor (e.g. cerebellar tremor) 5 Rest tremor Cognition (e.g. counting), gait or talking about the disease 6 usually increases the amplitude Intention tremor The tremor amplitude is the highest at the target. Usually 7 caused by cerebellar problems. Postural –kinetic tremor 8 Postural –kinetic tremor 9 Essential tremor is the most frequent cause of kinetic tremor. Postural –kinetic tremor 10 Always examine water drinking, writing and tableware use -- QoL Deep brain stimulation for tremor 11 Chorea The word chorea denotes rapid irregular muscle jerks that occur involuntarily and unpredictably in different parts of the body. Most important cause is12 Parkinson’s disease Ballism Large involuntary movements involving the whole extremity. Usually accompanies the chorea. Vascular lesion e.g. in the area of subthalamic13 nucleus can produce Athetosis abnormal movements that are slow, sinuous, and writhing in character. 14 Dystonia • Not a disease, it is a syndrome • Involuntary phasic, movement and/or • Sustained, involuntary, abnormal muscle contractions. -

Mobile Gait Analysis: from Prototype Towards Clinical Grade Wearable

FAU Studien aus der Informatik 6 Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable FAU Studien aus der Informatik Band 6 Herausgeber der Reihe: Björn Eskofier, Richard Lenz, Andreas Maier, Michael Philippsen, Lutz Schröder, Wolfgang Schröder-Preikschat, Marc Stamminger, Rolf Wanka Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Erlangen FAU University Press 2019 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Das Werk, einschließlich seiner Teile, ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die Rechte an allen Inhalten liegen bei ihren jeweiligen Autoren. Sie sind nutzbar unter der Creative Commons Lizenz BY-NC. Der vollständige Inhalt des Buchs ist als PDF über den OPUS Server der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg abrufbar: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-fau/home Bitte zitieren als Hannink, Julius. 2019. Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable. FAU Studies FAU Studien aus der Informatik Band 6. Erlangen: FAU University Press. DOI: 10.25593/978-3-96147-173-7 Verlag und Auslieferung: FAU University Press, Universitätsstraße 4, 91054 Erlangen Druck: docupoint GmbH ISBN: 978-3-96147-172-0 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-96147-173-7 (Online-Ausgabe) ISSN: 2509-9981 DOI: 10.25593/978-3-96147-173-7 Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Mobile Ganganalyse: Vom Prototyp in Richtung klinisch anwendbarer Systeme Der Technischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr.-Ing. -

Evaluating the Child with Unsteady Gait

Review Article Evaluating the child with unsteady gait Mohammed M. Jan, MBChB, FRCP(C). ABSTRACT From the Department of Pediatrics, King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Address correspondence and reprint request to: Prof. Mohammed M. S. Jan, Department of Pediatrics, King Abdul-Aziz University يعتبر خلل التوازن أثناء املشي من اﻷعراض الشائعة لدى اﻷطفال Hospital, PO Box 80215, Jeddah 21589, Kingdom of Saudi (Arabia. Tel. +996 (2) 6401000 Ext. 20208. Fax. +996 (2 بقسم الطوارئ واﻷعصاب. تتعدد أسباب خلل التوازن، ولكن E-mail: [email protected] .6403975 من أهم اولويات التقييم اﻷولى هو التأكد من عدم وجود التهاب أو ورم بالدماغ. التعرف علي املسببات احلميدة والغير عصبية ًأيضا eurological disorders are common in Saudi Arabia مهم لتفادى القيام بفحوصات متعددة دون احلاجة إليها أو تنومي Naccounting for up to 30% of all consultations to املريض باملستشفى. في هذه املقالة النقدية نقدم مراجعة حديثة pediatrics.1 Trauma, ingestion, and acute neurological عن تقييم الطفل املصاب بخلل التوازن مع مناقشة الفحوصات disorders are common, mainly as a result of improper الﻻزمة والعﻻج. قد يكون خلل التوازن ناجت عن مرض باملخيخ safety practices of many parents.2 Consanguineous أو مشكلة حسية، ًعلما بأن أمراض املخيخ قد تكون حادة، marriages also add to the problem, resulting in مزمنة، متدهورة، أو متقطعة. وتتعدد أسباب هذه املشكلة و increased prevalence of many inherited and genetic منها اﻹصابات، اﻻلتهابات، أمراض اﻻستقﻻب، العيوب اخللقية، neurological disorders.3,4 Unsteadiness and ataxia are واﻷورام. أما أسباب خلل التوازن الناجت عن مشاكل اﻹحساس relatively common neurological presentations of a فيكون بسبب تأثر في اﻷعصاب الطرفية أو احلبل الشوكي. -

Gait Disorders

What are the classical Gait Patterns for the Following Conditions? • Alzheimers Disease Gait Disorders • Hemiparetic Stroke • Parkinsons Disease T.Masud • Osteomalacia Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust • Lateral popliteal nerve palsy University of Nottingham University of Derby • Knee OA University of Southern Denmark • Vitamin B12 deficiency with dorsal column loss Statistical summaries of risk factors for falls From cohort studies- Perell 2001 RISK FACTOR Mean RR/OR Range Muscle weakness 4.4 (1.5-10.3) Falls history 3.0 (1.7-7.0) Gait deficit 2.9 (1.3-5.6) Balance deficit 2.9 (1.6-5.4) Use of assistive devices 2.6 (1.2-4.6) Visual deficit 2.5 (1.6-3.5) Arthritis 2.4 (1.9-2.7) Impaired ADLs 2.3 (1.5-3.1) Depression 2.2 (1.7-2.5) Cognitive impairment 1.8 (1.0-2.3) Age > 80 1.7 (1.1-2.5) Simple Model for Balance Balance Vision FALLS Vestibular Musculo- skeletal Proprioception Tactile sensation Activity & environmental hazards CNS Gait cycle [weight bearing] [progress] Running: stance 50% - swing 50%, then Asymmetry no double support period Stance phase Condition Disabled: increased bilateral stance phase Pain, weakness to increase double support period Impaired balance: vestibular, cerebellum dysfunction Clinical gait analysis Pattern Recognition of Gait Pattern recognition Hemiplegic Parkinsonian - Most quickly, recall from memory Apraxic Structured Approach Neuropathic - Hypothetico-deductive Ataxic - Basic gait knowledge / Anatomy Waddling Exhaustive strategy Spastic - Comprehensive and systematic evaluation Hyperkinetic Antalgic Gait Disorder in Older People High Level Gait Disorders by level of Sensorimotor Deficit Frontal Related • Apraxic •Cerebrovascular • Magnetic Low • Freezing High Middle •Dementia Level Level Level From- Alexander, Goldberg, Cleveland Clinic J Med 2005; 72: 592-600 High Level Gait Disorders High Level Gait Disorders Frontal Related Frontal Related •Cerebrovascular •Cerebrovascular •Dementia •Dementia •N.P. -

Pupil and Accomodation Abnormalities

PPUUPPIILL AANNDD AACCCCOOMMOODDAATTIIOONN AABBNNOORRMMAALLIITTIIEESS SympatheticSympathetic pathwaypathway ofof pupillarypupillary innervationinnervation PPuuppiillllaarryy lliigghhtt rreefflleexxeess ••PupilPupil diameterdiameter isis subjectsubject toto continuouscontinuous variationsvariations asas aa functionfunction ofof changeschanges inin luminanceluminance,, fixationfixation andand psychosensitivepsychosensitive stimulistimuli.. •• PupilsPupils mustmust bebe studiedstudied byby evaluatingevaluating theirtheir sizesize,, shapeshape,, symmetrysymmetry andand activityactivity ((dilationdilation andand constrictionconstriction).). •• ToTo evaluateevaluate sizesize andand symmetrysymmetry ofof pupilspupils,, patientspatients areare invitedinvited toto fixatefixate aa farawayfaraway objectobject,, whichwhich mustmust notnot bebe aa sourcesource ofof excessiveexcessive lightlight stimulationstimulation.. ••SSuubbsseeqquueennttllyy,, bbyy iilllluummiinnaattiinngg tthhee ppaattiieennttss’’ ffaaccee ffrroomm bbeellooww wwiitthh aa wweeaakk lliigghhtt ssoouurrccee,, bbootthh ppuuppiillss aarree ssiimmuullttaanneeoouussllyy oobbsseerrvveedd aanndd tthheeiirr ddiiaammeetteerrss aarree ddeetteerrmmiinneedd ((mmmm)).. •• IInn tthhee nnoorrmmaall ppooppuullaattiioonn,, ppuuppiill ddiiaammeetteerr tteennddss ttoo bbee ssmmaalllleerr iinn cchhiillddrreenn,, iinn tthhee eellddeerrllyy aanndd iinn ssuubbjjeeccttss wwiitthh ddaarrkk iirriiss.. •In general, anisocoria which changes with changes of luminance conditions must be considered pathologic,