Neurological History and Physical Examination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

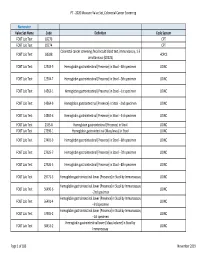

2020 Measure Value Set Colorectal Cancer Screening

PT ‐ 2020 Measure Value Set_Colorectal Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System FOBT Lab Test 82270 CPT FOBT Lab Test 82274 CPT Colorectal cancer screening; fecal occult blood test, immunoassay, 1‐3 FOBT Lab Test G0328 HCPCS simultaneous (G0328) FOBT Lab Test 12503‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐4th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 12504‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐5th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14563‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐1st specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14564‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐2nd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14565‐6 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐3rd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 2335‐8 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27396‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Mass/mass] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27401‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐6th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27925‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐7th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27926‐5 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐8th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 29771‐3 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay LOINC Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56490‐6 LOINC ‐‐2nd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56491‐4 LOINC ‐‐3rd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 57905‐2 -

9781441967237.Pdf

The Neurologic Diagnosis wwwwwwwwww Jack N. Alpert The Neurologic Diagnosis A Practical Bedside Approach Jack N. Alpert, MD St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital Department of Neurology University of Texas Medical School at Houston Houston, TX, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-6723-7 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-6724-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-6724-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2011941214 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identifi ed as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) In Memory of Morris B. -

Categorization of Functional Impairments in Human Locomotion

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 Categorization of Functional Impairments in Human Locomotion using the Methods of the Fusion of Multiple Sensors and Computational Intelligence Huiying Yu University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Biomedical Commons, and the Electrical and Electronics Commons Recommended Citation Yu, Huiying, "Categorization of Functional Impairments in Human Locomotion using the Methods of the Fusion of Multiple Sensors and Computational Intelligence" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2814. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2814 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATEGORIZATION OF FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENTS IN HUMAN LOCOMOTION USING THE METHODS OF THE FUSION OF MULTIPLE SENSORS AND COMPUTATIONAL INTELLIGENCE HUIYING YU Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering APPROVED: ________________________________ Thompson Sarkodie-Gyan, Ph.D., Chair ________________________________ Scott Starks, Ph.D. ________________________________ Richard Brower, M.D. ________________________________ Bill Tseng, Ph.D. ________________________________ Eric Spier, M.D. __________________________________ Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate -

Physical Therapy Practice

Physical Therapy Practice THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHOPAEDIC SECTION, APTA VOL. 18, NO. 2 2006 ORTHOPAEDIC CARDON REHABILITATION PRODUCTS, INC.™ Wurlitzer Industrial Park, 908 Niagara Falls Blvd. North Tonawanda, NY 14120 Telephone: 1-800-944-7868 • Fax: 716-297-0411 E-mail: [email protected] THE ACCEPTED STANDARD OF PERFORMANCE The Cardon Mobilization Table . Going beyond the third dimension . Now available with the patented option which eliminates the use of flexion and rotation levers. This allows the therapist to perform advanced manual therapy techniques with complete confidence and comfort with an ergonomically friendly design. The unique design provides more efficient and smooth setup while providing superior patient comfort. The option enhances patient care by allowing unsurpassed opportunity for more preciseness of treatment and monitoring of segments and joints. he design and concepts make this “T the best mobilization table manufactured today.” Professor Freddy Kaltenborn Autho, Int’l Lecturer in Manual Therapy he various sections have minimum flex “T allowing very accurate application of specific manual therapy techniques.” Olaf Evjenth ES! I would like to preview the Author, Int’l Lecturer in Manual Therapy Y Cardon Mobilization Table. Please rush your 15 minute VHS video (for standard model): SEE FOR Name: Title: YOURSELF Clinic/Institution: THESE Address: OUTSTANDING City: State: Zip Code: Telephone: Signature: FEATURES: CARDON REHABILITATION PRODUCTS, INC.™ • Accurate localization of the vertebral segment Wurlitzer Industrial Park, 908 Niagara Falls Blvd. • Precision and versatility of technique North Tonawanda, NY 14120 • Absolute control of the mobilization forces Telephone: 1-800-944-7868 • Fax: 716-297-0411 • Excellent stability for manipulation. E-mail: [email protected] Orthopaedic Practice Vol. -

Movement Disorders and Gait Disturbances

Movement disorders and gait disturbances Kovács Norbert PTE ÁOK Neurológiai Klinika Pécs 1 MD pathophysiology z Genetic mutation or environmental injury of basal ganglia functioning z Pallidum, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, caudate nucleus, pedunculopintine nucleus 2 Vitek JL. Mov Disord 2002;17(Supp 3):S49-62 Phenomenology in MD Hyperkinetic Isokinetic Hypokinetic • Tremor (regular) • Ataxia • Rigidity • Chorea • Bradykinesia • Ballism • Hypokinesia • Dystonia • Athetosis • Myoclonus (jerky) • Tic (jerky) 3 Hyperkinetic movements 4 Tremor classification More or less regular, sinusoid movements Any body parts can be affected (e.g. limbs, neck, trunc, vocal cords) Classification: • Intensity (invisible, barely visible, moderate, severe) • Frequency (slow or fast) • Position – Rest tremor (e.g. Parkinsonism) – Postural tremor (e.g. hyperthyroidism) – Kinetic tremor (e.g. essential tremor) – Intention tremor (e.g. cerebellar tremor) 5 Rest tremor Cognition (e.g. counting), gait or talking about the disease 6 usually increases the amplitude Intention tremor The tremor amplitude is the highest at the target. Usually 7 caused by cerebellar problems. Postural –kinetic tremor 8 Postural –kinetic tremor 9 Essential tremor is the most frequent cause of kinetic tremor. Postural –kinetic tremor 10 Always examine water drinking, writing and tableware use -- QoL Deep brain stimulation for tremor 11 Chorea The word chorea denotes rapid irregular muscle jerks that occur involuntarily and unpredictably in different parts of the body. Most important cause is12 Parkinson’s disease Ballism Large involuntary movements involving the whole extremity. Usually accompanies the chorea. Vascular lesion e.g. in the area of subthalamic13 nucleus can produce Athetosis abnormal movements that are slow, sinuous, and writhing in character. 14 Dystonia • Not a disease, it is a syndrome • Involuntary phasic, movement and/or • Sustained, involuntary, abnormal muscle contractions. -

Equinus Deformity in the Pediatric Patient: Causes, Evaluation, and Management

Equinus Deformity in the Pediatric Patient: Causes, Evaluation, and Management a,b,c Monique C. Gourdine-Shaw, DPM, LCDR, MSC, USN , c, c Bradley M. Lamm, DPM *, John E. Herzenberg, MD, FRCSC , d,e Anil Bhave, PT KEYWORDS Equinus Pediatric External fixation Achilles tendon lengthening Gastrocnemius recession Tendo-Achillis lengthening Different body and limb segments grow at different rates, inducing varying muscle tensions during growth.1 In addition, boys and girls grow at different rates.1 The rate of growth for girls spikes at ages 5, 7, 10, and 13 years.1 The estrogen-induced pubertal growth spurt in girls is one of the earliest manifestations of puberty. Growth of the legs and feet accelerates first, so that many girls have longer legs in proportion to their torso during the first year of puberty. The overall rate of growth tends to reach a peak velocity (as much as 7.5 to 10 cm) midway between thelarche and menarche and declines by the time menarche occurs.1 In the 2 years after menarche, most girls grow approximately 5 cm before growth ceases at maximal adult height.1 The rate of growth for boys spikes at ages 6, 11, and 14 years.1 Compared with girls’ early growth spurt, growth accelerates more slowly in boys and lasts longer, resulting in taller adult stature among men than women (on average, approximately 10 cm).1 The difference is attributed to the much greater potency of estradiol compared with testosterone in Two authors (BML and JEH) host an international teaching conference supported by Smith & Nephew. -

Mobile Gait Analysis: from Prototype Towards Clinical Grade Wearable

FAU Studien aus der Informatik 6 Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable FAU Studien aus der Informatik Band 6 Herausgeber der Reihe: Björn Eskofier, Richard Lenz, Andreas Maier, Michael Philippsen, Lutz Schröder, Wolfgang Schröder-Preikschat, Marc Stamminger, Rolf Wanka Julius Hannink Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Erlangen FAU University Press 2019 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Das Werk, einschließlich seiner Teile, ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die Rechte an allen Inhalten liegen bei ihren jeweiligen Autoren. Sie sind nutzbar unter der Creative Commons Lizenz BY-NC. Der vollständige Inhalt des Buchs ist als PDF über den OPUS Server der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg abrufbar: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-fau/home Bitte zitieren als Hannink, Julius. 2019. Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable. FAU Studies FAU Studien aus der Informatik Band 6. Erlangen: FAU University Press. DOI: 10.25593/978-3-96147-173-7 Verlag und Auslieferung: FAU University Press, Universitätsstraße 4, 91054 Erlangen Druck: docupoint GmbH ISBN: 978-3-96147-172-0 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-96147-173-7 (Online-Ausgabe) ISSN: 2509-9981 DOI: 10.25593/978-3-96147-173-7 Mobile Gait Analysis: From Prototype towards Clinical Grade Wearable Mobile Ganganalyse: Vom Prototyp in Richtung klinisch anwendbarer Systeme Der Technischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr.-Ing. -

Evaluating the Child with Unsteady Gait

Review Article Evaluating the child with unsteady gait Mohammed M. Jan, MBChB, FRCP(C). ABSTRACT From the Department of Pediatrics, King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Address correspondence and reprint request to: Prof. Mohammed M. S. Jan, Department of Pediatrics, King Abdul-Aziz University يعتبر خلل التوازن أثناء املشي من اﻷعراض الشائعة لدى اﻷطفال Hospital, PO Box 80215, Jeddah 21589, Kingdom of Saudi (Arabia. Tel. +996 (2) 6401000 Ext. 20208. Fax. +996 (2 بقسم الطوارئ واﻷعصاب. تتعدد أسباب خلل التوازن، ولكن E-mail: [email protected] .6403975 من أهم اولويات التقييم اﻷولى هو التأكد من عدم وجود التهاب أو ورم بالدماغ. التعرف علي املسببات احلميدة والغير عصبية ًأيضا eurological disorders are common in Saudi Arabia مهم لتفادى القيام بفحوصات متعددة دون احلاجة إليها أو تنومي Naccounting for up to 30% of all consultations to املريض باملستشفى. في هذه املقالة النقدية نقدم مراجعة حديثة pediatrics.1 Trauma, ingestion, and acute neurological عن تقييم الطفل املصاب بخلل التوازن مع مناقشة الفحوصات disorders are common, mainly as a result of improper الﻻزمة والعﻻج. قد يكون خلل التوازن ناجت عن مرض باملخيخ safety practices of many parents.2 Consanguineous أو مشكلة حسية، ًعلما بأن أمراض املخيخ قد تكون حادة، marriages also add to the problem, resulting in مزمنة، متدهورة، أو متقطعة. وتتعدد أسباب هذه املشكلة و increased prevalence of many inherited and genetic منها اﻹصابات، اﻻلتهابات، أمراض اﻻستقﻻب، العيوب اخللقية، neurological disorders.3,4 Unsteadiness and ataxia are واﻷورام. أما أسباب خلل التوازن الناجت عن مشاكل اﻹحساس relatively common neurological presentations of a فيكون بسبب تأثر في اﻷعصاب الطرفية أو احلبل الشوكي. -

Conversive Gait Disorder: You Cannot Miss This Diagnosis

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20140022 ARTICLE Conversive gait disorder: you cannot miss this diagnosis Distúrbio conversivo da marcha: você não pode deixar de fazer esse diagnóstico Péricles Maranhão-Filho1,2, Carlos Eduardo da Rocha e Silva3, Maurice Borges Vincent1 ABSTRACT Bizarre, purposeless movements and inconsistent findings are typical of conversive gaits. The objective of the present paper is to review some phenomenological aspects of twenty-five consecutive conversive gait disorder patients. Some variants are typical – knees give way-and-recover presentation, monoparetic, tremulous, and slow motion – allowing clinical diagnosis with high precision. Keywords: somatic symptom, conversive gait, neurological examination. RESUMO Movimentos bizarros, sem finalidade e inconsistentes são típicos das marchas conversivas. O objetivo deste artigo é descrever os aspectos fenomenológicos de vinte e cinco pacientes com distúrbio conversivo da marcha, salientando que algumas variantes são tão típicas – dobrando os joelhos e recuperando, monoparética, trêmula e em câmara lenta – que praticamente não possuem diagnóstico diferencial. Palavras-chave: sintoma somático, marcha conversiva, exame neurológico. The neurological examination as we know today, disorders”, which replaced the previous so-called “somato- emerged by the end of the 19th century, when signs that form disorders”9. would trustfully discriminate weakness due to structural The cases presented herein suggest that objective land- damage from hysteria became crucial1. Conversion disorder, marks do provide the neurologist with sturdy evidence for which may affect 11-300/100,000 individuals, remains a trustworthy conversive gait diagnosis. largely underdiagnosed, partially because its mechanisms are still unknown2,3. Conversive gait disorders correspond to approximately 3% (0-7%) of the movements’ disorders METHOD in specialized centres4,5. -

OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY for a TODDLER with CEREBRAL PALSY PRESENTING with DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS a Doctoral Project a Comprehe

OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH CEREBRAL PALSY PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS A Doctoral Project A Comprehensive Case Analysis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHYSICAL THERAPY by Amy K. Holthaus SUMMER 2015 © 2015 Amy K. Holthaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH CEREBRAL PALSY PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS A Doctoral Project by Amy K. Holthaus Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Katrin Mattern-Baxter, PT, DPT, PCS __________________________________, First Reader Brad Stockert, PT, PhD __________________________________, Second Reader Edward Barakatt, PT, PhD ____________________________ Date iii Student: Amy K. Holthaus I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________________, Department Chair ____________ Edward Barakatt, PT, PhD Date Department of Physical Therapy iv Abstract of OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH CEREBRAL PALSY PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS by Amy K. Holthaus A pediatric patient with cerebral palsy was seen for physical therapy treatment provided by a student for ten sessions from February 2014 to May 2014 at a university setting under the supervision of a licensed physical therapist. The patient was evaluated at the initial encounter with Gross Motor Function Measurement-66, Peabody Developmental Motor Scale-2 and Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, and a plan of care was established. Main goals for the patient were to improve development motor functions through increasing independent ambulation, functional balance and strength. -

Gait Disorders

What are the classical Gait Patterns for the Following Conditions? • Alzheimers Disease Gait Disorders • Hemiparetic Stroke • Parkinsons Disease T.Masud • Osteomalacia Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust • Lateral popliteal nerve palsy University of Nottingham University of Derby • Knee OA University of Southern Denmark • Vitamin B12 deficiency with dorsal column loss Statistical summaries of risk factors for falls From cohort studies- Perell 2001 RISK FACTOR Mean RR/OR Range Muscle weakness 4.4 (1.5-10.3) Falls history 3.0 (1.7-7.0) Gait deficit 2.9 (1.3-5.6) Balance deficit 2.9 (1.6-5.4) Use of assistive devices 2.6 (1.2-4.6) Visual deficit 2.5 (1.6-3.5) Arthritis 2.4 (1.9-2.7) Impaired ADLs 2.3 (1.5-3.1) Depression 2.2 (1.7-2.5) Cognitive impairment 1.8 (1.0-2.3) Age > 80 1.7 (1.1-2.5) Simple Model for Balance Balance Vision FALLS Vestibular Musculo- skeletal Proprioception Tactile sensation Activity & environmental hazards CNS Gait cycle [weight bearing] [progress] Running: stance 50% - swing 50%, then Asymmetry no double support period Stance phase Condition Disabled: increased bilateral stance phase Pain, weakness to increase double support period Impaired balance: vestibular, cerebellum dysfunction Clinical gait analysis Pattern Recognition of Gait Pattern recognition Hemiplegic Parkinsonian - Most quickly, recall from memory Apraxic Structured Approach Neuropathic - Hypothetico-deductive Ataxic - Basic gait knowledge / Anatomy Waddling Exhaustive strategy Spastic - Comprehensive and systematic evaluation Hyperkinetic Antalgic Gait Disorder in Older People High Level Gait Disorders by level of Sensorimotor Deficit Frontal Related • Apraxic •Cerebrovascular • Magnetic Low • Freezing High Middle •Dementia Level Level Level From- Alexander, Goldberg, Cleveland Clinic J Med 2005; 72: 592-600 High Level Gait Disorders High Level Gait Disorders Frontal Related Frontal Related •Cerebrovascular •Cerebrovascular •Dementia •Dementia •N.P. -

Gait Abnormalities in Functional Problems of the Lower Extremities and in Neurological Diseases

48 Review articles GAIT ABNORMALITIES IN FUNCTIONAL PROBLEMS OF THE LOWER EXTREMITIES AND IN NEUROLOGICAL DISEASES M. Becheva, PhD Medical University- Plovdiv, Medical College, Bulgaria, 120Buxton Bros. 4004 Plovdiv Abstract: Gait is a complex, automated and stereotyped motor activity that allows for movement of the body in an upright position. The investigation of gait is an integral part of the pathokinesiological study of the functional problems in any of the segments of the lower limbs. As the stereotype of walking changes at departure, stopping, turning, walking alongside another one, gait should be examined in different situations. In functional problems of the lower limbs and in some neurological diseases, the follow- ing abnormal gaits are detected: arthrogenic gait in extensional contractures of the hip or knee, walking in flexion contractures, "Gluteus maximus" gait, "Gluteus medius"gait, ataxic gait, hemiparetic (hemiplegic) gait, gait in parkinsonism, gait in paresis of plantar flexor, lameness in spasm of m. psoas major, gait in insufficiency of m. quadriceps femo- ris, gait in shortening of a lower limb, steppage gait and scissor gait. Adjusting abnormal gait is especially important to improve the functional condition of the patients in view of procuring a better quality of life. Keywords: abnormal gait, functional problems, neurological diseases. Introduction ground and allows the body to move forward. Gait is a complex stereotyped and auto- Gait is a conscious and volitional motor activity mated motor activity, which allows for move- [3]. ment of the body in an upright position. It 3. A complex coordination action during consists of several components: body movements, to maintain the center of grav- 1.