In the Light of Wisdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Ramakrishna Mission and Human

TOWARDS SERVING THE MANKIND: THE ROLE OF THE RAMAKRISHNA MISSION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA Karabi Mitra Bijoy Krishna Girls’ College Howrah, West Bengal, India sanjay_karabi @yahoo.com / [email protected] Abstract In Indian tradition religious development of a person is complete when he experiences the world within himself. The realization of the existence of the omnipresent Brahman --- the Great Spirit is the goal of the spiritual venture. Gradually traditional Hinduism developed negative elements born out of age-old superstitious practices. During the nineteenth century changes occurred in the socio-cultural sphere of colonial India. Challenges from Christianity and Brahmoism led the orthodox Hindus becoming defensive of their practices. Towards the end of the century the nationalist forces identified with traditional Hinduism. Sri Ramakrishna, a Bengali temple-priest propagated a new interpretation of the Hindu scriptures. Without formal education he could interpret the essence of the scriptures with an unprecedented simplicity. With a deep insight into the rapidly changing social scenario he realized the necessity of a humanist religious practice. He preached the message to serve the people as the representative of God. In an age of religious debates he practiced all the religions and attained at the same Truth. Swami Vivekananda, his closest disciple carried the message to the Western world. In the Conference of World religions held at Chicago (1893) he won the heart of the audience by a simple speech which reflected his deep belief in the humanist message of the Upanishads. Later on he was successful to establish the Ramakrishna Mission at Belur, West Bengal. -

ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22

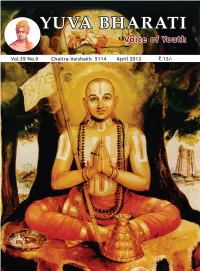

Vol.39 No.9 Chaitra-Vaishakh 5114 April 2012 R.15/- Editorial 03 Swami Vivekananda on his return to India-13 A Gigantic Plan 05 Fashion Man ... Role in Freedom Struggle 11 Sister Nivedita : Who Gave Her All to India-15 15 ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22 The Role of Saints In Building And Rebuilding Bharat 26 V.Senthil Kumar Sangh Inspired by Swamiji 32 Vivekananda Kendra Samachar 39 Single Copy R.15/- Annual R.160/- For 3 Yrs R.460/- Life (10 Yrs) R.1400/- Foreign Subscription: Annual - $40 US Dollar Life (10 years) - $400US Dollar (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) Yuva bharati - 1 - April 2012 Invocation çaìkaraà çaìkaräcäryaà keçavaà bädaräyaëam| sütrabhäñyakåtau vande bhagavantau punaù punaù|| I salute, again and again, the great teacher Aadi Shankaracharya, who is Lord Siva and Badarayana, who is Lord Vishnu, the venerable ones who wrote the Bhaashyaas and the Brahma-Sutras respectively. Yuva bharati - 2 - April 2012 Editorial Youth Icon… hroughout modern history youths have needed an icon. Once there were the Beetles; then there was John Lennon. TFor those youngsters who love martial arts there was Bruce Lee followed by Jackie Chan. Now in the visible youth culture of today who is the youth icon? The honest answer is Che Guevara. The cigar smoking good looking South American Marxist today looks at us from every T-shirt and stares from beyond his grave through facebook walls. Cult of Che Guevara is marketed in the every conceivable consumer item that a youth may use. And he has been a grand success. -

Sri Ramakrishna Math

Sri Ramakrishna Math 31, Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004, India & : 91-44-2462 1110 / 9498304690 email: [email protected] / website: www.chennaimath.org Catalogue of some of our publications… Buy books online at istore.chennaimath.org & ebooks at www.vedantaebooks.org Some of Our Publications... Sri Ramakrishna the Great Master Swami Saradananda / Tr. Jagadananda This book is the most comprehensive, authentic and critical estimate of the life, sadhana, and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. It is an English translation of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga written in Bengali by Swami Saradananda, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna and who is deemed an authority both as a philosopher and as a biographer. His biographical narrative of Sri Ramakrishna Volume 1 is based on his firsthand observations, assiduous collection of material from Pages 788 | Price ` 200 different authentic sources, and patient sifting of evidence. Known for his vast Volume 2 erudition, spirit of rational enquiry and far-reaching spiritual achievements, Pages 688 | Price ` 225 he has interspersed the narrative with lucid interpretations of various religious cults, mysticism, philosophy, and intricate problems connected with the theory and practice of religion. Translated faithfully into English by Swami Jagadananda, who was a disciple of the Holy Mother, this book may be ranked as one of the best specimens in hagiographic literature. The book also contains a chronology of important events in the life of Sri Ramakrishna, his horoscope, and a short but beautiful article by Swami Nirvedananda on the book and its author. This firsthand, authentic book is a must- read for everyone who wishes to know about and contemplate on the life of Sri Ramakrishna. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

“ That This House, on the 150Th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda

The year 2013 is a very important year in the eventful calendar of the Ramakrishna Mission. This year happens to be the 150th Birthday Anniversary of Swami Vivekanada. Swamiji, as we call him, life’s mission was to propagate the teachings of the Vedanta, in the light of realisation of Sri Ramakrishna who is his master, throughout the world. “Swamiji has left behind a rich legacy for the future generations, in his writings on the four yogas, speeches, poetic compositions, epistles etc are in his book of complete works of Swami Vivekanda.” His birthday celebration has been celebrated throughout the world, of note in January 2013 UK Parliament recognised the valuable contribution made by Swamaji. The statement from the UK Parliament is: “ That this House, on the 150th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda, recognises the valuable contribution made by him to interfaith dialogue at international level, encouraging and promoting harmony and understanding between religions through his renowned lectures and presentations at the first World Parliament of the Religions in Chicago in 1893, followed by his lecture tours in the US and England and mainland Europe; notes that these rectified and improved the understanding of the Hindu faith outside India and dwelt upon universal goodness found within all religions; further notes that he inspired thousands to selflessly serve the distressed and those in need and promoted an egalitarian society free of all kinds of discrimination; and welcome the celebrations of his 150th Birth Anniversary in the UK and throughout the World” Vedanta Society, Brisbane Chapter celebrated the 150th Birthday Celebration and the 176th Birthday Celebration of Sri Ramakrishna on the 9th March 2013. -

—No Bleed Here— Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness 23

Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness Niraj Kumar wami Vivekananda should be credited of transformation into a great power. On the with inspiring intellectuals to work for other hand, Asia emerged as the land of Bud Sand promote Asian integration. He dir dha. Edwin Arnold, who was then the principal ectly and indirectly influenced most of the early of Deccan College, Pune, wrote a biographical proponents of panAsianism. Okakura, Tagore, work on Buddha in verse titled Light of Asia in Sri Aurobindo, and Benoy Sarkar owe much to 1879. Buddha stirred Western imagination. The Swamiji for their panAsian views. book attracted Western intellectuals towards Swamiji’s marvellous and enthralling speech Buddhism. German philosophers like Arthur at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche saw Bud on 11 September 1893 and his subsequent popu dhism as the world religion. larity in the West and India moulded him into a Swamiji also fulfilled the expectations of spokesman for Asiatic civilization. Transcendentalists across the West. He did not Huston Smith, the renowned author of The limit himself merely to Hinduism; he spoke World’s Religions, which sold over two million about Buddhism at length during his Chicago copies, views Swamiji as the representative of the addresses. He devoted a complete speech to East. He states: ‘Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism’ on 26 Spiritually speaking, Vivekananda’s words and September 1893 and stated: ‘I repeat, Shakya presence at the 1893 World Parliament of Re Muni came not to destroy, but he was the fulfil ligions brought Asia to the West decisively. -

Spiritual Conversations with Swami Shankarananda Swami Tejasananda English Translation by Swami Satyapriyananda (Continued from the Previous Issue)

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on Significance of Symbols—III n the heart of all these ritualisms, there Istands one idea prominent above all the rest—the worship of a name. Those of you who have studied the older forms of Christianity, those of you who have studied the other religions of the world, perhaps have marked that there is this idea with them all, the worship of a name. A name is said to be very sacred. In the Bible we read that the holy name of God was considered sacred beyond compare, holy consciously or unconsciously, man found beyond everything. It was the holiest of all the glory of names. names, and it was thought that this very Again, we find that in many different Word was God. This is quite true. What is religions, holy personages have been this universe but name and form? Can you worshipped. They worship Krishna, they think without words? Word and thought worship Buddha, they worship Jesus, and so are inseparable. Try if anyone of you can forth. Then, there is the worship of saints; separate them. Whenever you think, you hundreds of them have been worshipped all are doing so through word forms. The one over the world, and why not? The vibration brings the other; thought brings the word, of light is everywhere. The owl sees it in the and the word brings the thought. Thus the dark. That shows it is there, though man whole universe is, as it were, the external cannot see it. To man, that vibration is only symbol of God, and behind that stands visible in the lamp, in the sun, in the moon, His grand name. -

Remembering Gandhi: Political Philosopher and Social Theorist

REMEMBERING GANDHI: POLITICAL PHILOSOPHER AND SOCIAL THEORIST Published by Salesian College Publication Sonada - Darjeeling - 734 209 Don Bosco Road, Siliguri Phone: (+91) 89189 85019 734 001 / Post Box No. 73 www.salesiancollege.ac.in [email protected] www.publications.salesiancollege.net [email protected] ii “My belief is that whenever you go into somebody’s head - anyone’s head - it’s all insecurity.... I live with that fear that in a minute everything could go away.” Andre Acimann, in the interniew on his books - Call me by Your name and Find Me, in Rich Juzwiak, “The Story Continues, after all” Times, November, 4, 2019, 91. Salesian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, X(2019) 2 REMEMBERING GANDHI: POLITICAL PHILOSOPHER AND SOCIAL THEORIST ISSN 0976-1861 December 2019 Vol. X, No.2 CONTENTS Editorial Remembering Mahatma as Gandhi: Gandhi as Political Philosopher and Social Theorist v Pius V Thomas Original Articles Gandhi and the Development Discourse Siby K. George 1 A Conciliatory Gaze: SNG on MK Gandhi and BR Ambedkar 23 George Thadathil Gandhi’s Legacy: Vandana Shiva as Gandhi’s Heir 51 Pius V Thomas and Violina Patowary Gandhi in the Tropics: Climate, Disease and Medicine 73 Bikash Sarma The Violence of Non-violence: Reading Nirad C Chaudhuri Rereading Gandhi 85 Jaydeep Chakrabarty Freedom, Authority and Care as Moral Postulates: Reexamining Gandhi’s Proposal for Ethical Reconstruction 95 Subhra Nag Decoding Gandhigiri: A Genealogy of a ‘popular’ Gandhi 111 Abhijit Ray iv General Commentaries Labour for Love or Love for Labour? 135 Shruti Sharma Production of a ‘degenerate’ form 149 Vasudeva K. -

YUVA BHARATI Voice of Youth

YUVA BHARATI Voice of Youth Vol.35 No.10 Chaitra-Vaisakh 5110 May 2008 Rs.10/- CONTENTS Editorial -P. Parameswaran 4 The Work Before us -P. Parameswaran 7 Spiritual Dimensions of Health -N.Krishnamoorti 15 Rama’s Art of Management -Dr. K.Subrahmanyam 25 The Narmada Parikrama --K.K.Venkatraman 30 Personality Development - A Yogic View -Sumant Chandwadkar 38 Single Copy Rs. 10/- Founder Editor Mananeeya Eknathji Ranade Annual Rs. 100/- For 3 Yrs Rs. 275/- Editor Life (10Yrs) Rs. 900/- Mananeeya P. Parameswaran Foreign Subscription Annual - $25US Dollar Editorial Office Life 10 Yrs - $250US Dollar 5, Singarachari Street (Plus Rs. 50/- for outstation Cheques) Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005 Published and printed by L.Madhavan on Ph: (044) 28440042 behalf of Vivekananda Kendra from 5, Email:[email protected] Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai- Web:www.vkendra.org 5. at M/s. RNR Printers and Publishers, 8, Thandavarayan Street, Triplicane, Chennai-5. Editor: P Parameswaran. YUVA BHARATI - May 2008 3 When we look back at Indo-Nepalese relationship through the historical perspectives, we Yadvaktra manasa-sarah pratilabdha-janma will find that Nepal should have been one of our most reliable friends, with inviolable bhasyaravinda-makaranda-rasam pibanti | cultural linkages existing from the dawn of history. Nepal has never wavered in its pratyasam-unmukha-vinita-vineya-bhrngah conviction that they are a Hindu Nation. Likewise, the Great Indian thinkers, even during Tan bhasya-vittaka-gurun pranamami murdhna || the renaissance period, like Swami Vivekananda and Mahayogi Aurobindo, had been unequivocally asserting that India is a Hindu Nation. India and Nepal, though politically and administratively separated and autonomous for historical reasons, Hindu Nationalism had always been the binding chord between the two. -

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda Swami Vivekananda (Bengali: [ʃami bibekanɔndo] ( listen); 12 January 1863 – 4 Swami Vivekananda July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (Bengali: [nɔrendronatʰ dɔto]), was an Indian Hindu monk, a chief disciple of the 19th-century Indian mystic Ramakrishna.[4][5] He was a key figure in the introduction of the Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world[6][7] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion during the late 19th century.[8] He was a major force in the revival of Hinduism in India, and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India.[9] Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission.[7] He is perhaps best known for his speech which began, "Sisters and brothers of America ...,"[10] in which he introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893. Born into an aristocratic Bengali Kayastha family of Calcutta, Vivekananda was inclined towards spirituality. He was influenced by his guru, Ramakrishna, from whom he learnt that all living beings were an embodiment of the divine self; therefore, service to God could be rendered by service to mankind. After Vivekananda in Chicago, September Ramakrishna's death, Vivekananda toured the Indian subcontinent extensively and 1893. On the left, Vivekananda wrote: acquired first-hand knowledge of the conditions prevailing in British India. He "one infinite pure and holy – beyond later travelled to the United States, representing India at the 1893 Parliament of the thought beyond qualities I bow down World's Religions. Vivekananda conducted hundreds of public and private lectures to thee".[1] and classes, disseminating tenets of Hindu philosophy in the United States, Personal England and Europe. -

New Arrivals May 2017

AMRITA VISHWA VIDYAPEETHAM UNIVERSITY AMRITAPURI CAMPUS CENTRAL LIBRARY NEW ARRIVALS BOOK MAY 2017 Sl. Acc. No Title Author Subject A bridge to eternity: Sri Ramakrishna and 1 48274 his monastic order Spiritual 2 48253 A Handbook of Ashtanga Sangraha VIDYANATH,R Spiritual A New Earth:Awakening to Your Life"s 3 48209 Purpose Tolle,Eckhart Spiritual Chattambi Swamikal, Advaita Cinta Paddhati :The Essence of Thiruvadikal 4 48281 Advaita Vidyadhiraja Spiritual Yatiswarananda, 5 48268 Adventures in Religious Life Swami Spiritual GAMBHIRANANDA 6 48277 Aitareya Upanisad Tr Spiritual Atmaramananda, 7 48189 Art Culture and Spirituality Swami Spiritual Ashokananda,Swa 8 48261 Avadhuta Gita mi Spritual 9 48258 Be the self Ganesan ,V Spiritual Beyond Duality: Biographical Sketches of Saint & Enlightened Spiritual Teachers of Williams,Norman 10 48279 the 20th Centuary comp. Spritual 11 48290 Bhagavatha Vahini Sathya Sai Baba Spiritual Bhajanamritam - 2 : Malayalam Devotional 12 48204 Songs of Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi Spiritual 13 48221 Bhakti: Means and the end Rama Devi Spiritual 14 48252 revelation ROY, Thomas Spiritual Breaking India:Western Interventions in 15 48202 Dravidian and Dalit Faultliness Malhotra, Rajiv Spiritual 16 48297 Condensed gospel of Sri Ramakrishna Sri Ramakrishna Spiritual 17 48269 Dakshinamurti Stotra Sankaracharya Spiritual JAGADISWARANA 18 48264 Devi Mahatmyam NDA, Swami Spiritual 19 48217 Discipleship and sadhana Tara Devi Spiritual Gambhirananda, 20 48267 Eight Upanisads Swami Spiritual From Holy Wanderings to the