Remembering Gandhi: Political Philosopher and Social Theorist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life Ad Afterlife of the Mahatma

Indi@logs Vol 1 2014, pp. 103-122, ISSN: 2339-8523 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ GADHI ISM VS . G ADHI GIRI : THE LIFE AD AFTERLIFE OF THE MAHATMA 1 MAKARAND R. P ARANJAPE Jawaharlal Nehru University [email protected] Received: 11-05-2013 Accepted: 01-10-2013 ABSTRACT This paper, which contrasts Rajkumar Hirani’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai (2006) with Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), is as much a celebration of Bollywood as of Gandhi. It is to the former that the credit for most effectively resurrecting the Mahatma should go, certainly much more so than to Gandhians or academics. For Bollywood literally revives the spirit of Gandhi by showing how irresistibly he continues to haunt India today. Not just in giving us Gandhigiri—a totally new way of doing Gandhi in the world—but in its perceptive representation of the threat that modernity poses to Gandhian thought is Lage Raho Munna Bhai remarkable. What is more, it also draws out the distinction between Gandhi as hallucination and the real afterlife of the Mahatma. The film’s enormous popularity at the box office—it grossed close to a billion rupees—is not just an index of its commercial success, but also proof of the responsive chord it struck in Indian audiences. But it is not just the genius and inventiveness of Bollywood cinema that is demonstrated in the film as much as the persistence and potency of Gandhi’s own ideas, which have the capacity to adapt themselves to unusual circumstances and times. Both Richard Attenborough’s Oscar-winning epic, and Rajkumar Hirani’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai show that Gandhi remains as media-savvy after his death as he was during his life. -

Nitya's Time with Ramana Maharshi

This is a compilation of all the significant references in Nitya Chaitanya Yati’s English writings to his time with Ramana Maharshi, from 1948 until the Maharshi’s death in 1950, as well as his continuing inspirational influence thereafter. As many people found, Ramana Maharshi had a life-changing influence on Nitya, and he frequently made reference to it in his talks. Nitya’s age in those years ranged from 23 to 25, during the period when he was a disciple of Dr. G.H. Mees. Editorial information is in brackets. Key: BU – Brihadaranyaka Upanishad DM – Psychology of Darsanamala L&B – Love and Blessings (autobiography) MOTS – Meditations on the Self SOC – In the Stream of Consciousness TA – That Alone T&R – Therapy and Realization in the Bhagavad Gita YS – Yoga Sutras (Living the Science of Harmonious Union) For years I strongly believed in the dynamics of pedagogy, until I came under the spell of silence surrounding the person of Ramana Maharshi. (L&B 24) It was in 1948 during my summer vacation that I first went to see Ramana Maharshi. As he was Dr. Mees’ guru, I went to him with great expectations. I had read many accounts about him and considered it a rare opportunity to meet such a person. Tiruvannamalai is a hot place. One does not feel quite comfortable there. But the morning hours are very fresh and lovely. The night abruptly comes to a close. This is followed by the golden light of the sun embracing everything, which in turn is accompanied by a very beautiful chanting of the priests. -

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

Mahatma Gandhi

CHAPTER 1 MAHATMA GANDHI To be Human is to be One with God Mahatma Gandhi: A brief outline The best sources for a detailed life of Mahatma Gandhi are his autobiography and the many collected works that appear under his name. In brief, he was born in India in 1869, was married at the age of 13, and traveled to study law in England at the age of 19. His first trip to South Africa was in 1893 at the request of Indians in that country. While at Pietermaritzburg he was ejected from the train for sitting in a compartment reserved for whites. He sided with the British during the Boer War (although his sympathies lay with the Boers). During the Zulu War he formed the Ambulance Corps to help wounded soldiers, but also to show his loyalty to the British Empire. After the Zulu War, Gandhi took a vow of celibacy, and began using nonviolence as way for attaining rights for Indians in South Africa. It was after the Zulu War that he began articulating the goal of life as attaining moksha, or oneness with God. It was also in South Africa that the word Satyagraha was coined. After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi left for India and worked for the independence of India from Britain. He was assassinated in 1948. Needless to say, this paragraph gives a brief timeline of Gandhi. Again, The Autobiography and Collected Works (which appear in the text as CWMG for Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi) offer detailed information on the Mahatma. The depiction of Gandhi’s philosophy and understanding of human nature in this chapter differs from most works on Gandhi by deliberately focusing on the influence of non-western cultures and his rejection and critique of capitalism Most Gandhian scholars present him as a person desperately trying to assimilate into the dominant capitalist culture, or mute his criticisms of capitalism. -

ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22

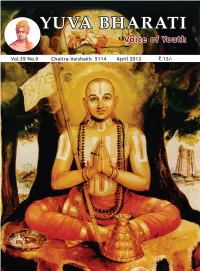

Vol.39 No.9 Chaitra-Vaishakh 5114 April 2012 R.15/- Editorial 03 Swami Vivekananda on his return to India-13 A Gigantic Plan 05 Fashion Man ... Role in Freedom Struggle 11 Sister Nivedita : Who Gave Her All to India-15 15 ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22 The Role of Saints In Building And Rebuilding Bharat 26 V.Senthil Kumar Sangh Inspired by Swamiji 32 Vivekananda Kendra Samachar 39 Single Copy R.15/- Annual R.160/- For 3 Yrs R.460/- Life (10 Yrs) R.1400/- Foreign Subscription: Annual - $40 US Dollar Life (10 years) - $400US Dollar (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) Yuva bharati - 1 - April 2012 Invocation çaìkaraà çaìkaräcäryaà keçavaà bädaräyaëam| sütrabhäñyakåtau vande bhagavantau punaù punaù|| I salute, again and again, the great teacher Aadi Shankaracharya, who is Lord Siva and Badarayana, who is Lord Vishnu, the venerable ones who wrote the Bhaashyaas and the Brahma-Sutras respectively. Yuva bharati - 2 - April 2012 Editorial Youth Icon… hroughout modern history youths have needed an icon. Once there were the Beetles; then there was John Lennon. TFor those youngsters who love martial arts there was Bruce Lee followed by Jackie Chan. Now in the visible youth culture of today who is the youth icon? The honest answer is Che Guevara. The cigar smoking good looking South American Marxist today looks at us from every T-shirt and stares from beyond his grave through facebook walls. Cult of Che Guevara is marketed in the every conceivable consumer item that a youth may use. And he has been a grand success. -

Sri Ramakrishna Math

Sri Ramakrishna Math 31, Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004, India & : 91-44-2462 1110 / 9498304690 email: [email protected] / website: www.chennaimath.org Catalogue of some of our publications… Buy books online at istore.chennaimath.org & ebooks at www.vedantaebooks.org Some of Our Publications... Sri Ramakrishna the Great Master Swami Saradananda / Tr. Jagadananda This book is the most comprehensive, authentic and critical estimate of the life, sadhana, and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. It is an English translation of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga written in Bengali by Swami Saradananda, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna and who is deemed an authority both as a philosopher and as a biographer. His biographical narrative of Sri Ramakrishna Volume 1 is based on his firsthand observations, assiduous collection of material from Pages 788 | Price ` 200 different authentic sources, and patient sifting of evidence. Known for his vast Volume 2 erudition, spirit of rational enquiry and far-reaching spiritual achievements, Pages 688 | Price ` 225 he has interspersed the narrative with lucid interpretations of various religious cults, mysticism, philosophy, and intricate problems connected with the theory and practice of religion. Translated faithfully into English by Swami Jagadananda, who was a disciple of the Holy Mother, this book may be ranked as one of the best specimens in hagiographic literature. The book also contains a chronology of important events in the life of Sri Ramakrishna, his horoscope, and a short but beautiful article by Swami Nirvedananda on the book and its author. This firsthand, authentic book is a must- read for everyone who wishes to know about and contemplate on the life of Sri Ramakrishna. -

Title a Revival of Gandhism in India? : Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna

A Revival of Gandhism in India? : Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Title Anna Hazare Author(s) ISHIZAKA, Shinya Citation INDAS Working Papers (2013), 12: 1-13 Issue Date 2013-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/178768 Right Type Research Paper Textversion author Kyoto University INDAS Working Papers No. 12 September 2013 A Revival of Gandhism in India? Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna Hazare Shinya ISHIZAKA 人間文化研究機構地域研究推進事業「現代インド地域研究」 NIHU Program Contemporary India Area Studies (INDAS) A Revival of Gandhism in India? Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna Hazare Shinya Ishizaka∗ A 2006 record hit Bollywood comedy film, Lage Raho Munna Bhai, where a member of the Mumbai mafia began to engage in Gandhigiri (a term meaning the tenets of Gandhian thinking, popularised by this film) by quitting dadagiri (the life of a gangster) in order to win the love of a lady, was sensationalised as the latest fashion in the revival of Gandhism. Anna Hazare (1937-), who has used fasting as an effective negotiation tactic in the anti-corruption movement in 2011, has been more recently acclaimed as a second Gandhi. Indian society has undergone a total sea change since the Indian freedom fighter M. K. Gandhi (1869-1948) passed away. So why Gandhi? And why now? Has the recent phenomena of the success of Munna Bhai and the rise of Anna’s movement shown that people in India today still recall Gandhi’s message? This paper examines the significance of these recent phenomena in the historical context of Gandhian activism in India after Gandhi. It further analyses how contemporary Gandhian activists perceive Anna Hazare and his movement, based upon interviews conducted with them during fieldwork in India in the period August-September 2011. -

Spanish JOURNAL of India STUDIES

iNDIALOGS sPANISH JOURNAL OF iNDIA STUDIES Nº 1 2014 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Editor/ Editora Felicity Hand (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Deputy Editors/ Editores adjuntos E. Guillermo Iglesias Díaz (Universidade de Vigo) Juan Ignacio Oliva Cruz (Universidad de La Laguna) Assistant Editors/ Editores de pruebas Eva González de Lucas (Instituto Cervantes, Kraków/Cracovia, Poland/Polonia) Maurice O’Connor (Universidad de Cádiz) Christopher Rollason (Independent Scholar) Advisory Board/ Comité Científico Ana Agud Aparicio (Universidad de Salamanca) Débora Betrisey Nadali (Universidad Complutense) Elleke Boehmer (University of Oxford, UK) Alida Carloni Franca (Universidad de Huelva) Isabel Carrera Suárez (Universidad de Oviedo) Pilar Cuder Domínguez (Universidad de Huelva) Bernd Dietz Guerrero (Universidad de Córdoba) Alberto Elena Díaz (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Taniya Gupta (Universidad de Granada) Belen Martín Lucas (Universidade de Vigo) Mauricio Martínez (Universidad de Los Andes y Universidad EAFIT, Bogotá, Colombia) Alejandra Moreno Álvarez (Universidad de Oviedo) Vijay Mishra (Murdoch University, Perth, Australia) Virginia Nieto Sandoval (Universidad Antonio de Nebrija) Antonia Navarro Tejero (Universidad de Córdoba) Dora Sales Salvador (Universidad Jaume I) Sunny Singh (London Metropolitan University, UK) Aruna Vasudev (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema NETPAC, India) Víctor Vélez (Universidad de Huelva) Layout/ Maquetación Despatx/ Office B11/144 Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Facultat -

Photos of God 3

chromolithographs that proliferated in the 1930S produced a similar effect through the semiosis created by their inter- ocularity and, of course, through their sheer ubiquity. The prints collectively, through their many hundred million acts of consumption, consolidate an internally referential landscape that came to exist in parallel throughout India. We are confronted with not so much a temporal 'traverse'41 as a spatial shadow, an ideal space and time that runs alongside everyday reality.42 We have already had some sense of the enduring popularity of images such as Kailash Pati Shankar through the variety of different versions that have ~\\~1:.~ ~u m~ "~Th:~~1:. \\~rou '\0 Qocument is tbe way in wbicb images entered everyday spaces. The anthropologist McKim Marriott's photographs from the 1940S and '50S in rural Uttar Pradesh and urban Maharashtra are one of the few records we have of this everday penetration. A 1952 photograph of a Brijbasi bromide postcard of Kailash Pati Shankar placed inside a copy of the Bhagvata Purana by a wealthy landlord (illus. 75) allows us to glimpse, through Marriott's lens, one small fragment of the spatial shadow of popular images insinuating ~..=.==-,~ themselves into the smallest (indeed thinnest) ;'-"=,::-,:- SHREE SATYANARAlN - - - J everyday spaces. We see here in its purest form the emergence of a new form of authority (the mass- 74 Narottam Narayan Sharma. Shree Satyanarain, 1950S offset print of produced visual) in conjunction with the old (the rural mid-1930S image. Published by S. S. Brijbasi. 'oralization'43 of texts by learned intermediaries), the local political consequences of which are described in of Brijbasi (the disseminator of the most significant more detail in chapter seven. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi.