MURDOCH RESEARCH REPOSITORY Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Observation and Range Extension of the Nudibranch Tenellia Catachroma (Burn, 1963) in Western Australia (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 129, 37–40, 2017 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS17003 A VICTORIAN EMIGRANT: FIRST OBSERVATION AND RANGE EXTENSION OF THE NUDIBRANCH TENELLIA CATACHROMA (BURN, 1963) IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA (MOLLUSCA: GASTROPODA) Matt J. NiMbs National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, PO Box 4321, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450, Australia Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The southwest coast of Western Australia is heavily influenced by the south-flowing Leeuwin Current. In summer, the current shifts and the north-flowing Capes Current delivers water from the south to nearshore environments and with it a supply of larvae from cooler waters. The nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) was considered restricted to Victorian waters; however, its discovery in eastern South Australia in 2013 revealed its capacity to expand its range west. In March 2017 a single individual was observed in shallow subtidal waters at Cape Peron, Western Australia, some 2000 km to the west of its previous range limit. Moreover, its distribution has extended northwards, possibly aided by the Capes Current, into a location of warming. This observation significantly increases the range for this Victorian emigrant to encompass most of the southern Australian coast, and also represents an equatorward shift at a time when the reverse is expected. Keywords: climate change, Cape Peron, range extension, Leeuwin Current, Capes Current The fionid nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) first found in southern NSW in 1979 (Rudman 1998), has was first described from two specimens found at Point been observed only a handful of times since and was also Danger, near Torquay, Victoria, in 1961 (Burn 1963). -

Chec List Marine and Coastal Biodiversity of Oaxaca, Mexico

Check List 9(2): 329–390, 2013 © 2013 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution ǡ PECIES * S ǤǦ ǡÀ ÀǦǡ Ǧ ǡ OF ×±×Ǧ±ǡ ÀǦǡ Ǧ ǡ ISTS María Torres-Huerta, Alberto Montoya-Márquez and Norma A. Barrientos-Luján L ǡ ǡǡǡǤͶǡͲͻͲʹǡǡ ǡ ȗ ǤǦǣ[email protected] ćĘęėĆĈęǣ ϐ Ǣ ǡǡ ϐǤǡ ǤǣͳȌ ǢʹȌ Ǥͳͻͺ ǯϐ ʹǡͳͷ ǡͳͷ ȋǡȌǤǡϐ ǡ Ǥǡϐ Ǣ ǡʹͶʹȋͳͳǤʹΨȌ ǡ groups (annelids, crustaceans and mollusks) represent about 44.0% (949 species) of all species recorded, while the ʹ ȋ͵ͷǤ͵ΨȌǤǡ not yet been recorded on the Oaxaca coast, including some platyhelminthes, rotifers, nematodes, oligochaetes, sipunculids, echiurans, tardigrades, pycnogonids, some crustaceans, brachiopods, chaetognaths, ascidians and cephalochordates. The ϐϐǢ Ǥ ēęėĔĉĚĈęĎĔē Madrigal and Andreu-Sánchez 2010; Jarquín-González The state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico (Figure 1) is and García-Madrigal 2010), mollusks (Rodríguez-Palacios known to harbor the highest continental faunistic and et al. 1988; Holguín-Quiñones and González-Pedraza ϐ ȋ Ǧ± et al. 1989; de León-Herrera 2000; Ramírez-González and ʹͲͲͶȌǤ Ǧ Barrientos-Luján 2007; Zamorano et al. 2008, 2010; Ríos- ǡ Jara et al. 2009; Reyes-Gómez et al. 2010), echinoderms (Benítez-Villalobos 2001; Zamorano et al. 2006; Benítez- ϐ Villalobos et alǤʹͲͲͺȌǡϐȋͳͻͻǢǦ Ǥ ǡ 1982; Tapia-García et alǤ ͳͻͻͷǢ ͳͻͻͺǢ Ǧ ϐ (cf. García-Mendoza et al. 2004). ǡ ǡ studies among taxonomic groups are not homogeneous: longer than others. Some of the main taxonomic groups ȋ ÀʹͲͲʹǢǦʹͲͲ͵ǢǦet al. -

A Historical Summary of the Distribution and Diet of Australian Sea Hares (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Aplysiidae) Matt J

Zoological Studies 56: 35 (2017) doi:10.6620/ZS.2017.56-35 Open Access A Historical Summary of the Distribution and Diet of Australian Sea Hares (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Aplysiidae) Matt J. Nimbs1,2,*, Richard C. Willan3, and Stephen D. A. Smith1,2 1National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, P.O. Box 4321, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450, Australia 2Marine Ecology Research Centre, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2456, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 3Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, G.P.O. Box 4646, Darwin, NT 0801, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 12 September 2017; Accepted 9 November 2017; Published 15 December 2017; Communicated by Yoko Nozawa) Matt J. Nimbs, Richard C. Willan, and Stephen D. A. Smith (2017) Recent studies have highlighted the great diversity of sea hares (Aplysiidae) in central New South Wales, but their distribution elsewhere in Australian waters has not previously been analysed. Despite the fact that they are often very abundant and occur in readily accessible coastal habitats, much of the published literature on Australian sea hares concentrates on their taxonomy. As a result, there is a paucity of information about their biology and ecology. This study, therefore, had the objective of compiling the available information on distribution and diet of aplysiids in continental Australia and its offshore island territories to identify important knowledge gaps and provide focus for future research efforts. Aplysiid diversity is highest in the subtropics on both sides of the Australian continent. Whilst animals in the genus Aplysia have the broadest diets, drawing from the three major algal groups, other aplysiids can be highly specialised, with a diet that is restricted to only one or a few species. -

Molecular Profiling of Cellular Identity and Plasticity in the Nervous System of Aplysia Californica

MOLECULAR PROFILING OF CELLULAR IDENTITY AND PLASTICITY IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM OF APLYSIA CALIFORNICA By CALEB JAMES BOSTWICK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Caleb James Bostwick To my family ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’d like to acknowledge the people who helped me to bring this dissertation to fruition. My advisor Dr. Leonid Moroz helped me come up with ideas and questions and encouraged me to generate more data and perform more extensive analyses than I would have previously thought possible. Dr. Andrea Kohn helped keep the lab organized and running. Yelena Bobkova provided animal care, dissection, and molecular biology expertise as well as friendship and support. Tanya Moroz assisted in cDNA library construction and the ganglia plasticity experiments in addition to brightening the general lab atmosphere. Dr. Peter Williams aided me in finding ways to better explain and document my computational biology techniques. Dr. Shaun Mukherjee was a friend who made lab meetings more bearable. Dr. Gabrielle Winters assisted me by providing assistance with molecular biology in the lab, asking insightful questions, proofreading my dissertation, and by being a generous and supportive partner during our many years of graduate study. Dr. Emily Dabe was a colleague and friend with whom I discussed bioinformatics methods and techniques and shared laughs. I thank my university and my graduate committee (Dr. Thomas Foster, Dr. David Borchelt, and Dr. Richard Yost), as well as Dr. Jada Lewis for her support and encouragement. -

Your Vet Autumn 8106.Indd

AUTUMN 2011 Cruciate disease: The great curse Cruciate ligaments are one of the most Diagnosis is based on physical examination, important structures within the knee of palpation of affected joints, bones and local humans, dogs and cats. Disease of the muscles, and the performance of a ‘cranial cruciate ligaments is one of the most drawer sign’ or ‘cranial tibial thrust’ test. common causes of hind limb lameness that Suites 17-19 vets treat. Signifi cant weakening of the thigh muscles Ocean Village Shopping Centre of the affected leg(s) is a common fi nding. Kilpa Court While the condition is very common in An audible ‘clicking’ may be heard when City Beach WA 6015 dogs, it can also occur in cats, sometimes the patient walks or the stifl e is palpated secondary to trauma, and sometimes through range of motion, indicating Phone 08 9245 1977 secondary to obesity, old age and concurrent possible internal tearing. Palpation of the arthritis of the joints. In dogs there are some joint compartment may show increased Fax 08 9245 2136 vets who also believe in a genetic breed- and joint fl uid or joint capsule thickening. Email offi [email protected] sex related link. This problem is so important Web www.citybeachvet.com.au in dog health that a 2005 study in the USA Blood tests are usually normal, unless the estimated that dog owners spent US$1.32 patient has concurrent hormonal diseases, Our Vets billion treating this disease! many of which will predispose to obesity. Dr Neville Robertson The function of healthy cruciate ligaments X-rays are usually performed, and BVSc(Syd), MVS(Murd) in the knee is to stabilise the forces of the sometimes a joint fl uid sample will also Dr Alan Wade knee that might otherwise push the shinbone be needed. -

Long-Term Monitoring Protocol for PORE/GOGA

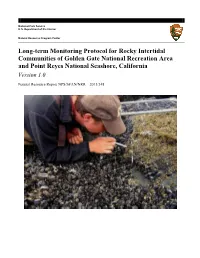

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Long-term Monitoring Protocol for Rocky Intertidal Communities of Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Point Reyes National Seashore, California Version 1.0 Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2011/348 ON THE COVER Dave Press counting invertebrates at Slide Ranch, Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Photograph by: Marcus Koenen Long-term Monitoring Protocol for Rocky Intertidal Communities of Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Point Reyes National Seashore, California Version 1.0 Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2011/348 Karah Ammann1 Peter Raimondi1 Ben Becker2 Dale Roberts3 Darren Fong4 Dave Press5 Marcus Koenen5 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology 4Golden Gate National Recreation Area Center for Ocean Health/Long Marine Lab National Park Service University of California Building 1061, Fort Cronkhite Santa Cruz, CA, 95060 Sausalito, California 94903 2Pacific Coast Science and Learning Center 5Inventory and Monitoring Program National Park Service National Park Service Point Reyes National Seashore San Francisco Bay Area I&M Network One Bear Valley Road Building 1063, Fort Cronkhite Point Reyes Station, California 94956 Sausalito, California 94903 3Inventory and Monitoring Program National Park Service Point Reyes National Seashore One Bear Valley Road Point Reyes Station, California 94956 April 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. -

East Coast Marine Shells; Descriptions of Shore Mollusks Together With

fi*": \ EAST COAST MARINE SHELLS / A • •:? e p "I have seen A curious child, who dwelt upon a tract Of Inland ground, applying to his ear The .convolutions of a smooth-lipp'd shell; To yi'hJ|3h in silence hush'd, his very soul ListehM' .Intensely and his countenance soon Brightened' with joy: for murmerings from within Were heai>^, — sonorous cadences, whereby. To his b^ief, the monitor express 'd Myster.4?>us union with its native sea." Wordsworth 11 S 6^^ r EAST COAST MARINE SHELLS Descriptions of shore mollusks together with many living below tide mark, from Maine to Texas inclusive, especially Florida With more than one thousand drawings and photographs By MAXWELL SMITH EDWARDS BROTHERS, INC. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN J 1937 Copyright 1937 MAXWELL SMITH PUNTZO IN D,S.A. LUhoprinted by Edwards B'olheri. Inc.. LUhtiprinters and Publishert Ann Arbor, Michigan. iQfj INTRODUCTION lilTno has not felt the urge to explore the quiet lagoon, the sandy beach, the coral reef, the Isolated sandbar, the wide muddy tidal flat, or the rock-bound coast? How many rich harvests of specimens do these yield the collector from time to time? This volume is intended to answer at least some of these questions. From the viewpoint of the biologist, artist, engineer, or craftsman, shellfish present lessons in development, construction, symme- try, harmony and color which are almost unique. To the novice an acquaint- ance with these creatures will reveal an entirely new world which, in addi- tion to affording real pleasure, will supply much of practical value. Life is indeed limitless and among the lesser animals this is particularly true. -

South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study

MARINE RESERVE IMPLEMENTATION SOUTH COAST SOUTH COAST TERRESTRIAL AND MARINE RESERVE INTEGRATION STUDY PROJECT #713 NATIONAL RESERVE SYSTEM COOPERATIVE PROGRAM Final Report: MRIP/SC-10/1997 A collaborative project between CALM Marine Conservation Branch and South Coast Region A project funded by Environment Australia Prepared by J G Colman Marine Conservation Branch March 1998 Marine Conservation Branch Department of Conservation and Land Management 47 Henry Street South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study Fremantle, Western Australia, 6160 ii South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study Research and the collation of information presented in this report was undertaken with funding provided by Environment Australia. The project was undertaken for the National Reserves System Cooperative Program (Project #713). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Commonwealth Government, the Minister for the Environment, or the Secretary, Environment Australia This report may be cited as South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study. Copies of the report may be borrowed from the library: Environment Australia Biodiversity Group GPO Box 636 CANBERRA ACT 2601 AUSTRALIA or The Librarian Science and Information Division Department of Conservation and Land Management PO Box 51 WANNEROO WA 6065 AUSTRALIA Cover - Bremer Bay and the Fitzgerald River National Park - Landsat TM imagery digitally enhanced by Satellite Remote Sensing Services, Department of Land Administration (DOLA), Western Australia. Satellite data provided from the Australian Coastal Atlas by ACRES. iii South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Currently, there are no marine conservation reserves along the south coast of Western Australia, although most of the coastal terrestrial reserves contain marine areas between high and low water marks. -

Seasonal and Algal Diet-Driven Patterns of the Digestive Microbiota

Gobet et al. Microbiome (2018) 6:60 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0430-7 RESEARCH Open Access Seasonal and algal diet-driven patterns of the digestive microbiota of the European abalone Haliotis tuberculata, a generalist marine herbivore Angélique Gobet1* , Laëtitia Mest1, Morgan Perennou2, Simon M Dittami1, Claire Caralp3, Céline Coulombet4, Sylvain Huchette4, Sabine Roussel3, Gurvan Michel1* and Catherine Leblanc1* Abstract Background: Holobionts have a digestive microbiota with catabolic abilities allowing the degradation of complex dietary compounds for the host. In terrestrial herbivores, the digestive microbiota is known to degrade complex polysaccharides from land plants while in marine herbivores, the digestive microbiota is poorly characterized. Most of the latter are generalists and consume red, green, and brown macroalgae, three distinct lineages characterized by a specific composition in complex polysaccharides, which represent half of their biomass. Subsequently, each macroalga features a specific epiphytic microbiota, and the digestive microbiota of marine herbivores is expected to vary with a monospecific algal diet. We investigated the effect of four monospecific diets (Palmaria palmata, Ulva lactuca, Saccharina latissima, Laminaria digitata) on the composition and specificity of the digestive microbiota of a generalist marine herbivore, the abalone, farmed in a temperate coastal area over a year. The microbiota from the abalone digestive gland was sampled every 2 months and explored using metabarcoding. Results: Diversity and multivariate analyses showed that patterns of the microbiota were significantly linked to seasonal variations of contextual parameters but not directly to a specific algal diet. Three core genera: Psychrilyobacter, Mycoplasma,andVibrio constantly dominated the microbiota in the abalone digestive gland. -

Download?Dac=C2010-0-27653- 598 7&Isbn=9781439840740&Doi=10.1201/B11113-10&Format=Pdf 599 Barber, P

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.448144; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Seascape genomics reveals population structure and local adaptation in a widespread coral 2 reef snail, Coralliophila violacea (Kiener, 1836) 3 4 Sara E. Simmonds1*, Samantha H. Cheng1,2, Allison L. Fritts-Penniman1, Gusti Ngurah 5 Mahardika3, Paul H. Barber1 6 7 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Los Angeles, 612 8 Charles E. Young Dr. East, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; 9 2Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central 10 Park West, New York, NY 10024, USA; 11 3Animal Biomedical and Molecular Biology Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, 12 Udayana University Bali, Jl. Raya Sesetan, Gg. Markisa 6, Denpasar, Bali 80223, Indonesia; 13 14 *Corresponding author’s current address: [email protected], Department of Biological 15 Sciences, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725-1515 16 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 Local adaptation to different environments may reinforce neutral evolutionary 20 divergence, especially in populations in the periphery of a species’ geographic range. 21 Seascape genomics (high-throughput genomics coupled with ocean climate databases) 22 facilitates the exploration of neutral and adaptive variation in concert, developing a 23 clearer picture of processes driving local adaptation in marine populations. This study 24 used a seascape genomics approach to test the relative roles of neutral and adaptive 25 processes shaping population divergence of a widespread coral reef snail, Coralliophila 26 violacea. -

![Toxins of Animals) [Biological-Origin Toxins]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0935/toxins-of-animals-biological-origin-toxins-4430935.webp)

Toxins of Animals) [Biological-Origin Toxins]

4: Zootoxins (toxins of animals) [Biological-origin toxins] Distinction should be made between poisonous animals – those with toxins in their skin or other organs and which are toxic on ingestion – and venomous animals – those with specialised structures for production and delivery of toxins (venoms) to prey species or adversaries. Halstead (1988) published a monumental review of poisonous and venomous marine animals. A world list of snake venoms and other animal toxins including bee venoms, sawfly toxins, amphibian and fish toxins has been compiled by Theakston & Kamiguti (2002). Animals acquire toxins by one of three methods (Mebs 2001): • expression of genes coding for the toxin structures • metabolic synthesis (production of secondary metabolites) • uptake, storage and sequestration of toxins produced by other organisms (microbes, plants, or other animals) References: Halstead BW (1988) Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World. 2nd revised edition. The Darwin Press Inc., Princeton, New Jersey. Mebs D (2001) Toxicity in animals. Trends in evolution? Toxicon 39:87-96. Theakston RDG , Kamiguti AS (2002) A list of animal toxins and some other natural products with biological activity. Toxicon 40:579-651. PROTOZOA (PROTISTA) - DINOFLAGELLATES See Marine Microalgal (Dinoflagellate & Diatom) Toxins ARTHROPODS - INSECTS Sawfly larval peptides Core data Common sources: Lophyrotoma interrupta (Australian cattle-poisoning sawfly larvae) Arge pullata (European birch sawfly larvae) Perreyia flavipes & P. lepida (South American sawfly larvae) Animals affected: cattle, sheep, pigs Mode of action: uncharacterised Poisoning circumstances: consumption of larvae (dead & alive) at base of trees or on pasture Main effects: acute liver necrosis Diagnosis: pathology + evidence of larval presence Therapy: nil Prevention: deny access Syndrome names: sawfly larval poisoning, sawfly poisoning Chemical structure: Lophyrotomin [L] is a linear octapeptide (Oelrichs et al. -

アマクサアメフラシおよびゾウアメフラシのインクと皮膚抽出物の イセエビに対する摂食阻害作用 Chemical Defenses in the Skin and the Ink of Sea Hares Aplysia Juliana and Aplysia Gigantea

日本ベントス学会誌 71: 11–16( 2016) アメフラシ類の化学防御 Japanese Journal of Benthology アマクサアメフラシおよびゾウアメフラシのインクと皮膚抽出物の イセエビに対する摂食阻害作用 Chemical defenses in the skin and the ink of sea hares Aplysia juliana and Aplysia gigantea 林原信子・神尾道也 * 東京海洋大学.〒108–8477 東京都港区港南 4–5–7 Nobuko HAYASHIHARA and Michiya KAMIO* Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, 4–5–7 Konan, Minato, Tokyo 108–8477, Japan Abstract: Chemical defense using secretion of ink containing purple pigments derived from red algae is common in sea hares. Aplysia juliana, however, prefers green algae, and thus, its ink is white, not purple. Since opaline, the sea haresʼ other defensive secretion, is also white, ink and opaline were not distinguished from each other in previous experiments. Thus, de- terrence of this white ink alone towards predators has never been tested. In this study, we tested the deterrence of the white ink of A. juliana as well as the extract of their skin, using the Japanese spiny lobster Panulirus japonicus as a model predator. Parallel experiments on Aplysia gigantea, a sea hare with purple ink, were performed to test whether P. japonicus is deterred by purple ink. The skin extract, but not the white ink, of A. juliana was deterrent. In contrast, purple ink, but not the skin extract, of A. gigantea was deterrent. These results show that the skin of A. juliana contains defensive chemicals against P. japonicus, whereas the white ink itself does not. Key Words: chemical defense, chemical ecology, deterrent, white ink, aplysioviolin, phycoerythrobilin 害(Aggio & Derby 2008; Kamio et al. 2010a; Kicklighter & はじめに Derby 2006; Nusnbaum & Derby 2010b),摂食刺激効果を持 つアミノ酸類による疑似食物効果(phagomimic)( Kick- アメフラシ類(Anaspidea, Aplysiidae)は浅海域に生息す lighter et al.