South Coast Terrestrial and Marine Reserve Integration Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Community Composition of the Xiphophora Gladiata Dominated Subzone of the Tasmanian Sublittoral Fringe

Papers and Proceedings ol the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 123, 1989 191 AN ANALYSIS OF THE COMMUNITY COMPOSITION OF THE XIPHOPHORA GLADIATA DOMINATED SUBZONE OF THE TASMANIAN SUBLITTORAL FRINGE by E. L. Rice (with five tables and nine text-figures) RICE, E.L., 1989 (31:x): An analysis of the community composition of the Xiphophora iladiata dominated subzone of the Tasmanian sublittoral fringe. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 123: I 91-209. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.123.191 ISSN 0080-4703. Biological Sciences Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Halifax Research Laboratory, PO Box 550, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 2S7, Canada; formerly Department of Botany, University of Tasmania The rocky shore sublittoral fringe of the oceanic coasts of Tasmania contains a subzone dominated by the large brown alga Xiphophora iladiata. The community composition of this subzone is here examined at fourteen sites. The phytal and fauna! assemblages are analysed by principal co-ordinate, classification and nodal analyses. This subzone is found to have a high species richness. including species which had been thought to occupy only higher or lower tidal levels. It is suggested that both plant and animal assemblages are strongly influenced by wave exposure, freshwater run-off and geography. Key Words: marine community composition, sublittoral fringe, Xiphophora, multivariate analyses. INTRODUCTION (Bennett & Pope 1960). Thus, on the oceanic coasts of Tasmania it is possible to define a Xiphophora The rocky shores of southeastern Australia are subzone, dominated by X. g/adiata, which marks known to be occupied primarily by barnacles and the highest limit of the sublittoral fringe on very molluscs in the upper intertidal (Underwood 1981), exposed shores and represents the upper sublittoral while algae dominate at midshore level and below. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Macquarie River Bird Trail

Bird Watching Trail Guide Acknowledgements RiverSmart Australia Limited would like to thank the following for their assistance in making this trail and publication a reality. Tim and Janis Hosking, and the other members of the Dubbo Field Naturalists and Conservation Society, who assisted with technical information about the various sites, the bird list and with some of the photos. Thanks also to Jim Dutton for providing bird list details for the Burrendong Arboretum. Photographers. Photographs were kindly provided by Brian O’Leary, Neil Zoglauer, Julian Robinson, Lisa Minner, Debbie Love, Tim Hosking, Dione Carter, Dan Giselsson, Tim Ralph and Bill Phillips. This project received financial support from the Australian Bird Environment Foundation of Sacred kingfisher photo: Dan Giselsson BirdLife Australia. Thanks to Warren Shire Council, Sarah Derrett and Ashley Wielinga in particular, for their assistance in relation to the Tiger Bay site. Thanks also to Philippa Lawrence, Sprout Design and Mapping Services Australia. THE MACQuarIE RIVER TraILS First published 2014 The Macquarie valley, in the heart of NSW is one of the The preparation of this guide was coordinated by the not-for-profit organisation Riversmart State’s — and indeed Australia’s — best kept secrets, until now. Australia Ltd. Please consider making a tax deductible donation to our blue bucket fund so we can keep doing our work in the interests of healthy and sustainable rivers. Macquarie River Trails (www.rivertrails.com.au), launched in late 2011, is designed to let you explore the many attractions www.riversmart.org.au and wonders of this rich farming region, one that is blessed See outside back cover for more about our work with a vibrant river, the iconic Maquarie Marshes, friendly people and a laid back lifestyle. -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Regional Bird Monitoring Annual Report 2018-2019

BirdLife Australia BirdLife Australia (Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) was founded in 1901 and works to conserve native birds and biological diversity in Australasia and Antarctica, through the study and management of birds and their habitats, and the education and involvement of the community. BirdLife Australia produces a range of publications, including Emu, a quarterly scientific journal; Wingspan, a quarterly magazine for all members; Conservation Statements; BirdLife Australia Monographs; the BirdLife Australia Report series; and the Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. It also maintains a comprehensive ornithological library and several scientific databases covering bird distribution and biology. Membership of BirdLife Australia is open to anyone interested in birds and their habitats, and concerned about the future of our avifauna. For further information about membership, subscriptions and database access, contact BirdLife Australia 60 Leicester Street, Suite 2-05 Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Tel: (Australia): (03) 9347 0757 Fax: (03) 9347 9323 (Overseas): +613 9347 0757 Fax: +613 9347 9323 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended citation: BirdLife Australia (2020). Melbourne Water Regional Bird Monitoring Project. Annual Report 2018-19. Unpublished report prepared by D.G. Quin, B. Clarke-Wood, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks and K. Herman for Melbourne Water by (BirdLife Australia, Carlton) This report was prepared by BirdLife Australia under contract to Melbourne Water. Disclaimers This publication may be of assistance to you and every effort has been undertaken to ensure that the information presented within is accurate. BirdLife Australia does not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Appendices Appendices

APPENDICES APPENDICES APPENDIX 1 – PUBLICATIONS SCIENTIFIC PAPERS Aidoo EN, Ute Mueller U, Hyndes GA, and Ryan Braccini M. 2015. Is a global quantitative KL. 2016. The effects of measurement uncertainty assessment of shark populations warranted? on spatial characterisation of recreational fishing Fisheries, 40: 492–501. catch rates. Fisheries Research 181: 1–13. Braccini M. 2016. Experts have different Andrews KR, Williams AJ, Fernandez-Silva I, perceptions of the management and conservation Newman SJ, Copus JM, Wakefield CB, Randall JE, status of sharks. Annals of Marine Biology and and Bowen BW. 2016. Phylogeny of deepwater Research 3: 1012. snappers (Genus Etelis) reveals a cryptic species pair in the Indo-Pacific and Pleistocene invasion of Braccini M, Aires-da-Silva A, and Taylor I. 2016. the Atlantic. Molecular Phylogenetics and Incorporating movement in the modelling of shark Evolution 100: 361-371. and ray population dynamics: approaches and management implications. Reviews in Fish Biology Bellchambers LM, Gaughan D, Wise B, Jackson G, and Fisheries 26: 13–24. and Fletcher WJ. 2016. Adopting Marine Stewardship Council certification of Western Caputi N, de Lestang S, Reid C, Hesp A, and How J. Australian fisheries at a jurisdictional level: the 2015. Maximum economic yield of the western benefits and challenges. Fisheries Research 183: rock lobster fishery of Western Australia after 609-616. moving from effort to quota control. Marine Policy, 51: 452-464. Bellchambers LM, Fisher EA, Harry AV, and Travaille KL. 2016. Identifying potential risks for Charles A, Westlund L, Bartley DM, Fletcher WJ, Marine Stewardship Council assessment and Garcia S, Govan H, and Sanders J. -

First Observation and Range Extension of the Nudibranch Tenellia Catachroma (Burn, 1963) in Western Australia (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 129, 37–40, 2017 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS17003 A VICTORIAN EMIGRANT: FIRST OBSERVATION AND RANGE EXTENSION OF THE NUDIBRANCH TENELLIA CATACHROMA (BURN, 1963) IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA (MOLLUSCA: GASTROPODA) Matt J. NiMbs National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, PO Box 4321, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450, Australia Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The southwest coast of Western Australia is heavily influenced by the south-flowing Leeuwin Current. In summer, the current shifts and the north-flowing Capes Current delivers water from the south to nearshore environments and with it a supply of larvae from cooler waters. The nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) was considered restricted to Victorian waters; however, its discovery in eastern South Australia in 2013 revealed its capacity to expand its range west. In March 2017 a single individual was observed in shallow subtidal waters at Cape Peron, Western Australia, some 2000 km to the west of its previous range limit. Moreover, its distribution has extended northwards, possibly aided by the Capes Current, into a location of warming. This observation significantly increases the range for this Victorian emigrant to encompass most of the southern Australian coast, and also represents an equatorward shift at a time when the reverse is expected. Keywords: climate change, Cape Peron, range extension, Leeuwin Current, Capes Current The fionid nudibranch Tenellia catachroma (Burn, 1963) first found in southern NSW in 1979 (Rudman 1998), has was first described from two specimens found at Point been observed only a handful of times since and was also Danger, near Torquay, Victoria, in 1961 (Burn 1963). -

Working Together

Working together Achievements 2014–2015 Contents Foreword 4 Leading natural resources management 5 Measuring performance 7 Managing water 9 Managing land condition 11 Managing island parks 13 Managing Seal Bay 15 Managing coasts and seas 17 Managing biodiversity 19 Managing fire 21 Managing threatened plants 23 2015© Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Managing glossy black-cockatoos 25 ISBNs Printed: 978-1-921595-19-6 On-line: 978-1-921595-20-2 Managing feral animals 27 This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Managing koalas 29 Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. Managing weeds 31 All images within this document are credited to Natural Resources Kangaroo Island unless stated otherwise. Working with volunteers 33 Front cover image: Ivy Male helps Heiri Klein to plant glossy black-cockatoo habitat. Working with junior primary students 35 Back cover image: Green carpenter bee. Working with primary students 37 Work outlined in this document is funded by: Working with land managers 39 1 2 2 Foreword With the release of the State Government’s The board and Kangaroo Island Council top economic priorities, the Kangaroo Island are advocating for a feral cat free island. region has been placed firmly in the spotlight Eradication of feral cats will take considerable with Kangaroo Island Natural Resources government, private and community resources. -

Working Together Our Achievements 2009 – 2016

Working together Our achievements 2009 – 2016 Photo and logos needed 1 2016© Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources ISBN: 978-1-921595-24-0 This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. All images within this document are credited to Natural Resources Kangaroo Island unless stated otherwise. Front cover image: Travis Bell and Grant Flanagan inspecting crop health as part of the AgKI Potential Project. Work outline in this document is funded by: 2 2 Message from the Presiding Member 4 Message from the Regional Director 5 Socio-economic Snapshot 6 Culture & Heritage Snapshot 8 Flora Snapshot 10 Fauna Snapshot 14 Marine & Coastal Snapshot 18 Freshwater Snapshot 22 Land Condition Snapshot 26 Biosecurity & Pests Snapshot 30 Climate Change Snapshot 34 Community Engagement & Capacity Building Snapshot 38 A New NRM Plan for KI 42 3 3 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING MEMBER The inaugural Kangaroo Island Natural Resources 2009, fencing off native vegetation, installing creek crossings Management (NRM) Plan 2009–2019 was prepared when and liming acid soils. Kangaroo Island was declared one of eight South Australian However, some systems are out of balance, particularly where NRM regions under the Natural Resources Management Act human activities have tipped the scales, and many plant 2004, and while Kangaroo Island may be the smallest region and animal species continue to decline in numbers on the geographically, it is certainly one of the most precious! island, including top order predators such as the Rosenberg’s The Kangaroo Island community is deeply connected to goanna and osprey. -

Recovery Plan for Nationally Threatened Plant Species on Kangaroo Island South Australia

Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board Australian Government Title: Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia © Department of Environment, Water & Natural Resources This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the sources but no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources PO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Citation Taylor, D.A. (2012). Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia. Cover Photos: The nationally threatened species Leionema equestre on the Hog Bay Road, eastern Kangaroo Island (Photo D. Taylor) Acknowledgements This Plan was developed with the guidance, support and input of the Kangaroo Island Threatened Plant Steering Committee and the Kangaroo Island Threatened Plant Recovery Team. Members included Kylie Moritz, Graeme Moss, Vicki-Jo Russell, Tim Reynolds, Yvonne Steed, Peter Copley, Annie Bond, Mary-Anne Healy, Bill Haddrill, Wendy Stubbs, Robyn Molsher, Tim Jury, Phil Pisanu, Doug Bickerton, Phil Ainsley and Angela Duffy. Valuable advice regarding the ecology, identification and location of threatened plant populations was received from Ida and Garth Jackson, Bev and Dean Overton and Rick Davies. The support of the Kangaroo Island staff of the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources was also greatly appreciated. Funding for the preparation of this plan was provided by the Australian Government, Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board and the Threatened Species Network (World Wide Fund for Nature). -

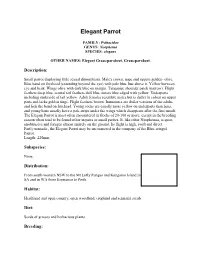

Elegant Parrot

Elegant Parrot FAMILY: Psittacidae GENUS: Neophema SPECIES: elegans OTHER NAMES: Elegant Grass-parakeet, Grass-parakeet. Description: Small parrot displaying little sexual dimorphism. Male's crown, nape and uppers golden- olive. Blue band on forehead (extending beyond the eye) with pale blue line above it. Yellow between eye and beak. Wings olive with dark blue on margin. Turquoise shoulder patch (narrow). Flight feathers deep blue, central tail feathers dull blue, outers blue edged with yellow. Underparts including underside of tail yellow. Adult females resemble males but is duller in colour on upper parts and lacks golden tinge. Flight feathers brown. Immatures are duller versions of the adults and lack the band on forehead. Young cocks are usually more yellow on underparts than hens, and young hens usually have a pale stripe under the wings which disappears after the first moult. The Elegant Parrot is most often encountered in flocks of 20-100 or more, except in the breeding season when tend to be found either in pairs or small parties. It, like other Neophemas, is quiet, unobtrusive and forages almost entirely on the ground. Its flight is high, swift and direct. Partly nomadic, the Elegant Parrot may be encountered in the company of the Blue-winged Parrot. Length: 225mm. Subspecies: None. Distribution: From south-western NSW to the Mt Lofty Ranges and Kangaroo Island in SA and in WA from Esperance to Perth. Habitat: Heathland and open country, open woodland, cropland and semiarid scrub. Diet: Seeds of grasses and herbacious plants. Breeding: August-January. The usual nesting site is a small tree cavity near the ground.