3.2 Conservation Value of Scrub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain </. C. Greig and A. B. Cooper Primitive breeds of sheep and goats, such as the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, could be in danger of disappearing with the present rapid decline in pastoral farming. The authors, both members of the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources in Edinburgh University, point out that, quite apart from their historical and cultural interest, these breeds have an important part to play in modern livestock breeding, which needs a constant infusion of new genes from unimproved breeds to get the benefits of hybrid vigour. Moreover these primitive breeds are able to use the poor land and live in the harsh environment which no modern hybrid sheep can stand. Recent work on primitive breeds of sheep and goats in Scotland has drawn attention not only to the necessity for conserving them, but also to the fact that there is no organisation taking a direct scientific in- terest in them. Primitive livestock strains are the jetsam of the Agricul- tural Revolution, and they tend to survive in Europe's peripheral regions. The sheep breeds are the best examples, such as the sheep of Ushant, off the Brittany coast, the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, the Shetland sheep, the Soay sheep of St Kilda, and the Manx Loaghtan breed. Presumably all have survived because of their isolation in these remote and usually infertile areas. A 'primitive breed' is a livestock breed which has remained relatively unchanged through the last 200 years of modern animal-breeding techniques. The word 'primitive' is perhaps unfortunate, since it implies qualities which are obsolete or undeveloped. -

Deborah Schiffrin Editor

Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications Deborah Schiffrin editor Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications Deborah Schiffrin editor Georgetown University Press, Washington, D.C. 20057 BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTICE Since this series has been variously and confusingly cited as: George- town University Monographic Series on Languages and Linguistics, Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics, Reports of the Annual Round Table Meetings on Linguistics and Language Study, etc., beginning with the 1973 volume, the title of the series was changed. The new title of the series includes the year of a Round Table and omits both the monograph number and the meeting number, thus: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984, with the regular abbreviation GURT '84. Full bibliographic references should show the form: Kempson, Ruth M. 1984. Pragmatics, anaphora, and logical form. In: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984. Edited by Deborah Schiffrin. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 1-10. Copyright (§) 1984 by Georgetown University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Number: 58-31607 ISBN 0-87840-119-9 ISSN 0196-7207 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks James E. Alatis Dean, School of Languages and Linguistics vii Introduction Deborah Schiffrin Chair, Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984 ix Meaning and Use Ruth M. Kempson Pragmatics, anaphora, and logical form 1 Laurence R. Horn Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and R-based implicature 11 William Labov Intensity 43 Michael L. Geis On semantic and pragmatic competence 71 Form and Function Sandra A. -

Ame R I Ca N Pr

A Century of ME R I CA N R IDE A P August 1 3th- 16th 2014 R EGULAR A DMISSION Adults $9.00 | Kids 6-12 $5.00 | Age 5 & under Free W EDNESDAY S PECIAL All Day Adult $5.00 |Kids 6-12 $3.00 | Age 5 & under Free Fair Passes & Carnival Armbands Discounted July 1st - August 1 2th Courtesy of Grants Pass Daily Courier 2 2014 Schedule of Events SUBJECT TO CHANGE 9 AM 4-H/FFA Poultry Showmanship/Conformation Show (RP) 5:30 PM Open Div. F PeeWee Swine Contest (SB) 9 AM Open Div. E Rabbit Show (PR) 5:45 PM Barrow Show Awards (SB) ADMISSION & PARKING INFORMATION: (may move to Thursday, check with superintendent) 5:30 PM FFA Beef Showmanship (JLB) CARNIVAL ARMBANDS: 9 AM -5 PM 4-H Mini-Meal/Food Prep Contest (EB) 6 PM 4-H Beef Showmanship (JLB) Special prices July 1-August 12: 10 AM Open Barrow Show (SB) 6:30-8:30 PM $20 One-day pass (reg. price $28) 1:30 PM 4-H Breeding Sheep Show (JLB) Midway Stage-Mercy $55 Four-day pass (reg. price $80) 4:30 PM FFA Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) Grandstand- Truck & Tractor Pulls, Monster Trucks 5 PM FFA Breeding Sheep and Market Sheep Show (JLB) 7 PM Butterscotch Block closes FAIR SEASON PASSES: 5 PM 4-H Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) 8:30-10 PM PM Special prices July 1-August 12: 6:30 4-H Cavy Showmanship Show (L) Midway Stage-All Night Cowboys PM PM $30 adult (reg. -

Asterwildlife Wildfowl on the Lake Langley Country Park Beautiful, Tranquil and Historic with a Variety of Habitats for Wildlife and Year Round Activities for All

Wildlife walks Berkshirein Our favourite five #AsterWildlife Wildfowl on the Lake Langley Country Park Beautiful, tranquil and historic with a variety of habitats for wildlife and year round activities for all. Buckinghamshire SL0 0LS Green flag Award Lilly Hill Park A green flag awarded, public open space with diverse habitats for birds, bats, insects, wild flowers, grasslands and trees. Bracknell RG12 2RX Flora & Fauna Englemere Pond A lovely Nature reserve on the doorstep, all sorts of flora and fauna to be seen throughout the year and great dog walking routes too. Ascot SL5 8BA Beautiful Bluebells Moor Copse Nature Reserve Peaceful, relaxing, and easy terrain leads up into beautiful Tidmarsh. A little off the beaten path but well worth a visit. Reading RG8 8HE Looking for Lizards Finchampstead Ridges If you walk slowly and quietly on a sunny day you may be lucky enough to spot a common lizard or slow worm basking in the warmth of the sun. Wokingham RG45 6AE Wildlife walks Cornwallin Our favourite five #AsterWildlife Good for Birdwatching Marazion Beach If you’re into bird spotting you’ll love it here plus you’ll find lots of like-minded people to chat to. Don’t forget your binoculars! Marazion TR17 0AA Seal Spotting Godrevy Natural beauty at its best. An easy walk, stunning views and stacks of wildlife. Share the beaches with the seals.......that’s how close to nature you are. South West Coast Path, Hayle TR27 5ED Perfect Ponds Tehidy Country Park For short or long walks, there’s something for everyone. The squirrels are friendly and the ponds have lots of geese, ducks and swans. -

Midlan Hawthorn

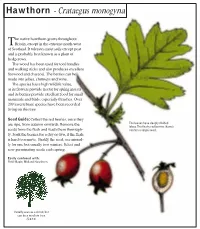

18 F L E S H Y F R U I T S F L E S H Y F R U I T S 19 Hawthorn - Crataegus monogyna Midland Hawthorn - Crataegus laevigata idland hawthorn is the he native hawthorn grows throughout Mrarer of the two native TBritain, except in the extreme north-west hawthorn species and the of Scotland. It tolerates most soils except peat one that is more likely to and is probably best known as a plant of grow into a small tree. It is hedgerows. found on heavy soils in shady The wood has been used for tool handles woodlands, or growing along road- and walking sticks and also produces excellent sides and in gardens, usually in the firewood and charcoal. The berries can be south east of Britain. Many ornamen- made into jellies, chutneys and wine. tal forms have been created, including The species has a high wildlife value, ‘Paul’s Scarlet’, which is frequently seen as its flowers provide nectar for spring insects in towns and cities. and its berries provide excellent food for small Medium tree (6:8:10) As with hawthorn, the wood has been mammals and birds, especially thrushes. Over used for tool handles and walking sticks, 209 invertebrate species have been recorded its fluted stems making it particularly use- living on this tree. ful for the latter. The berries can be made into jellies, chutneys and wine. Seed Guide: Collect the red berries, once they are ripe, from autumn onwards. Remove the The leaves have deeply divided The flowers provide nectar for spring lobes.The fleshy red berries (haws) insects, the berries excellent food for seeds from the flesh and wash them thorough- contain a single seed. -

CATAIR Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA April 24, 2020 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes ............................................................................................................................................4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes .................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ............................................................................................. 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes.................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers .................................................................... 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ...................................................................................................................... 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers.................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure .............................................................................................................................. 30 PG05 – Scie nt if ic Spec ies Code .................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ..................................................................................................... -

A Survey of Leach's Petrels on Shetland in 2011

Contents Scottish Birds 32:1 (2012) 2 President’s Foreword K. Shaw PAPERS 3 The status and distribution of the Lesser Whitethroat in Dumfries & Galloway R. Mearns & B. Mearns 13 The selection of tree species by nesting Magpies in Edinburgh H.E.M. Dott 22 A survey of Leach’s Petrels on Shetland in 2011 W.T.S. Miles, R.M. Tallack, P.V. Harvey, P.M. Ellis, R. Riddington, G. Tyler, S.C. Gear, J.D. Okill, J.G Brown & N. Harper SHORT NOTES 30 Guillemot with yellow bare parts on Bass Rock J.F. Lloyd & N. Wiggin 31 Reduced breeding of Gannets on Bass Rock in 2011 J. Hunt & J.B. Nelson 32 Attempted predation of Pink-footed Geese by a Peregrine D. Hawker 32 Sparrowhawk nest predation by Carrion Crow - unique footage recorded from a nest camera M. Thornton, H. & L. Coventry 35 Black-headed Gulls eating Hawthorn berries J. Busby OBITUARIES 36 Dr Raymond Hewson D. Jenkins & A. Watson 37 Jean Murray (Jan) Donnan B. Smith ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 38 Scottish seabirds - past, present and future S. Wanless & M.P. Harris 46 NEWS AND NOTICES 48 SOC SPOTLIGHT: the Fife Branch K. Dick, I.G. Cumming, P. Taylor & R. Armstrong 51 FIELD NOTE: Long-tailed Tits J. Maxwell 52 International Wader Study Group conference at Strathpeffer, September 2011 B. Kalejta Summers 54 Siskin and Skylark for company D. Watson 56 NOTES AND COMMENT 57 BOOK REVIEWS 60 RINGERS’ ROUNDUP R. Duncan 66 Twelve Mediterranean Gulls at Buckhaven, Fife on 7 September 2011 - a new Scottish record count J.S. -

DEFRA Blanket Bog Review V021107

Review of Blanket Bog Management and Restoration TECHNICAL REPORT TO DEFRA PROJECT No. CTE0513 H O’Brien, J C Labadz & D P Butcher Nottingham Trent University School of Animal Rural & Environmental Sciences Brackenhurst Southwell NG25 0QF [email protected] 01636 817017 April 2007 CONTENTS 1 Introduction............................................................................................ 9 1.1 Principal Aims.................................................................................. 9 1.2 Objectives....................................................................................... 9 2 Methodology ......................................................................................... 10 2.1 Published Literature ....................................................................... 10 2.2 Grey Literature .............................................................................. 10 2.3 Interviews..................................................................................... 10 3 Blanket Bog: Definition, Classification and Characteristics........................... 12 3.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 12 3.2 Definition of Blanket Bog ................................................................ 12 3.3 Classification of Blanket Bogs .......................................................... 14 3.4 Blanket Bog Formation ................................................................... 16 3.5 Hydrology of Blanket Bogs ............................................................. -

Hinton Ampner Archaeological Survey Report, 2007

WA Heritage THE NATIONAL TRUST ESTATE AT HINTON AMPNER, HAMPSHIRE Archaeological and Historical Survey Volume 1: Historical Text & Appendices Prepared for The National Trust Thames & Solent Region Stowe Gardens Buckingham MK18 5EH by WA Heritage Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 67660.01 January 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008 all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 National Trust Estate WA Heritage Hinton Ampner, Hampshire THE NATIONAL TRUST ESTATE HINTON AMPNER HAMPSHIRE Archaeological and Historical Survey CONTENTS Summary …………..………………………………………………………………...…………iii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….….v 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background.................................................................................................1 1.2 Survey and Report Standards.................................................................................1 2 STRATEGY..............................................................................................2 2.1 Survey methodology ...............................................................................................2 2.2 Time expenditure ....................................................................................................2 2.3 Limitations to background research ........................................................................3 2.4 Limitations of the field -

Investigations Into Senescence and Oxidative Metabolism in Gentian

Abstract 0 Investigations into senescence and oxidative metabolism in gentian and petunia flowers A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Biotechnology at the University of Canterbury by Shugai Zhang 2008 Abstract I Abstract Using gentian and petunia as the experimental systems, potential alternative post-harvest treatments for cut flowers were explored in this project. Pulsing with GA3 (1 to 100 µM) or sucrose (3%, w/v) solutions delayed the rate of senescence of flowers on cut gentian stems. The retardation of flower senescence by GA3 in both single flower and half petal systems was accompanied by a delay in petal discoloration. The delay in ion leakage increase or fresh weight loss was observed following treatment with 5 or 10 µM GA3 of the flowers at the unopen bud stage. Ultrastructural analysis showed that in the cells of the lower part of a petal around the vein region, appearance of senescence-associated features such as degradation of cell membranes, cytoplasm and organelles was faster in water control than in GA3 treatment. In particular, degeneration of chloroplasts including thylakoids and chloroplast envelope was retarded in response to GA3 treatment. In the cells of the top part of a petal, more carotenoids-containing chromoplasts were found after GA3 application than in water control. In petunia, treatment with 6% of ethanol or 0.3 mM of STS during the flower opening stage was effective to delay senescence of detached flowers. The longevity of isolated petunia petals treated with 6% ethanol was nearly twice as long as when they were held in water. -

ECOLOGICAL and ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE of STUDYING PROPAGATION TECHNIQUES of COMMON HAWTHORN Crataegus Monogyna Jacq. G

СИБИРСКИЙ ЛЕСНОЙ ЖУРНАЛ. 2019. № 4. С. 63–67 UDC 581.16/581.6/581.9:634.17 ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF STUDYING PROPAGATION TECHNIQUES OF COMMON HAWTHORN Crataegus monogyna Jacq. G. Özyurt, Z. Yücesan, N. Ak, E. Oktan, A. Ö. Üçler Karadeniz Technical University Trabzon, 61080 Turkey E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 11.04.2019 Climate change as a fact of global warming requires the development of different perspectives on the planning and implementation of sustainable forestry techniques. Increasing temperatures cause drought on a global basis. In connection with, this using drought tolerant species in afforestation work is of great importance. In recent years Crataegus L. species (hawthorn) are also involved in afforestation. One of these species, C. monogyna, is characterized by drought tolerance. Furthermore, C. monogyna is the most important nonwood forest product species of Turkey. Hawthorn is widely used in medicine (treatment of coronary heart diseases), and cosmetics industry, agriculture and animal husbandry and human nutrition. On the other hand, it is used in erosion control, afforestation, industrial energy resources and for landscaping. Economic and ecological contribution of hawthorn to the national economy is quite high. Therefore, determination of suitable generative and vegetative reproduction techniques and vast production of seedlings of hawthorn species are extremely important. The characteristics of generative and vegetative propagation of Crataegus are discussed. For generative propagation of hawthorn species, the most effective and suitable procedure is treatment of seeds in ash solution. For vegetative propagation in culture in vitro the growth induced by BA (benzyladenine) and IBA (indole butyric acid) hormones increases the rate of callus formation and rooting. -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m.