Pusey Was Spread Upon the Permanent Records of the Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

A TEN YEAR REPORT the Institute of Politics

A TEN YEAR REPORT 1966-1967 to 1976-1977 The Institute of Politics John Fitzgerald Kennedy School of Government Harvard University A TEN YEAR REPORT 1966-1967 to 1976-1977 The Institute of Politics John Fitzgerald Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 1 The Institute of Politics Richard E. Neustadt, Director, 1966-1971 The urge to found an Institute of Politics had little to do with Harvard. It came, rather, from a natural concern of President Kennedy's family and friends after his death. The JFK library, al ready planned to house his presidential papers, was also to have been a headquarters for him when he retired from the Presidency. Now it would be not a living center focussed on him, active in the present, facing the future, but instead only an archive and museum faced to ward the past. The Institute was somehow to provide the living ele ment in what might otherwise soon turn into a "dead" memorial. Nathan Pusey, at the time Harvard's President, then took an initiative with Robert Kennedy, proposing that the Institute be made a permanent part of Harvard's Graduate School of Public Administra tion. The School—uniquely among Harvard's several parts—would be named for an individual, John F. Kennedy. Robert Kennedy ac cepted; these two things were done. The Kennedy Library Corpora tion, a fund-raising body charged to build the Library, contributed endowment for an Institute at Harvard. The University renamed its School the John Fitzgerald Kennedy School of Government, and created within it the Institute of Politics. -

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital By

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital by K. Page Boyer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Educational Leadership) at the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair LEO Lecturer II John Burl Artis Professor M. Robert Fraser Copyright 2016 by K. Page Boyer All Rights Reserved i Dedication To my family “To know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.” ~ Nicolaus Copernicus ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair of my dissertation committee, for her probity and guidance concerning theories of school administration and leadership, organizational theory and development, educational law, legal and regulatory issues in educational administration, and curriculum deliberation and development. Thank you to Dr. John Burl Artis for his deep knowledge, political sentience, and keen sense of humor concerning all facets of educational leadership. Thank you to Dr. M. Robert Fraser for his rigorous theoretical challenges and intellectual acuity concerning the history of Christianity and Christian Thought and how both pertain to teaching and learning in America’s colleges and universities today. I am indebted to Baker Library at Dartmouth College, Regenstein Library at The University of Chicago, the Widener and Houghton Libraries at Harvard University, and the Hatcher Graduate Library at the University of Michigan for their stewardship of inestimably valuable resources. Finally, I want to thank my family for their enduring faith, hope, and love, united with a formidable sense of humor, passion, optimism, and a prodigious ability to dream. -

A Social and Cultural History of the Federal Prohibition of Psilocybin

A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL PROHIBITION OF PSILOCYBIN A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by COLIN WARK Dr. John F. Galliher, Dissertation Supervisor AUGUST 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL PROHIBITION OF PSILOCYBIN presented by Colin Wark, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John F. Galliher Professor Wayne H. Brekhus Professor Jaber F. Gubrium Professor Victoria Johnson Professor Theodore Koditschek ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank a group of people that includes J. Kenneth Benson, Wayne Brekhus, Deborah Cohen, John F. Galliher, Jay Gubrium, Victoria Johnson, Theodore Koditschek, Clarence Lo, Kyle Miller, Ibitola Pearce, Diane Rodgers, Paul Sturgis and Dieter Ullrich. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ ii NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY ............................................................................................ iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………1 2. BIOGRAPHICAL OVERVIEW OF THE LIVES OF TIMOTHY LEARY AND RICHARDALPERT…………………………………………………….……….20 3. MASS MEDIA COVERAGE OF PSILOCYBIN AS WELL AS THE LIVES OF RICHARD ALPERT AND TIMOTHY -

The Year 1944 Was Notable for Various Reasons: D-Day, Rome Was

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF ADAMS HOUSE, HARVARD COLLEGE GALAXY GAZER William Liller '48, Adams House Master, 1969-73 The year 1944 was notable for various reasons: D-Day, Rome was liberated, the war in the Pacific was finally going well, FDR got re- elected for a fourth term, and although we didn't know it at the time, the atom bomb was almost ready to be dropped. (Alas, the Red Sox, with Ted Williams now a Marine pilot, finished fourth; the hapless Boston Braves finished sixth.) 1944 was also the start of my connection with Harvard, a couple of weeks after the invasion of Normandy. After attending public schools in my home town of Atlanta, I was shipped off "to finish", and I spent my last two high school years at Mercersburg Academy in Pennsylvania. When senior year came around, I had only a vague idea of going to Harvard, known to me mainly for its football team and a world-famous astronomer, Harlow Shapley. My father, a successful adman, had no input in my decision; it was my best friend, Shaw Livermore, who talked me into applying. His dad had a Harvard degree; mine was a UPenn dropout. My grades had been only slightly better than average, but somehow, I got accepted. Maybe it was because the southern boy quota was unfilled, or maybe it was that that Harvard was scraping the barrel in those grim Bill Liller in Chile, 1996 WW II years. Whatever the reason, I got lucky: I had not applied to any other university. We began our Harvard experience in July of 1944. -

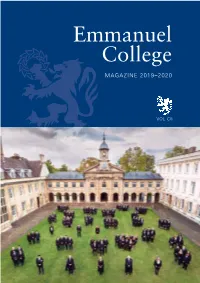

View 2020 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOL CII MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2019–2020 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2021. Enquiries, news about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or submitted via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/keepintouch/. General correspondence about the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP is the person to contact about obituaries. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, and especially to Carey Pleasance for assistance with obituaries and to Amanda Goode, the college archivist, whose knowledge and energy make an outstanding contribution. Back issues The college holds an extensive stock of back numbers of the Magazine. Requests for copies of these should be addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. -

John H. Finley, Jr., 91, Classicist at Harvard for 43 Years, Is Dead

Figure F1 “John Harvard, Founder, 1638” Bronze statue, 1884, by Daniel Chester French of John Harvard (1607–1638), an English minister who on his deathbed made a bequest of his library and half of his estate to the “schoale or Colledge recently undertaken” by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The grateful recipients named the college in his honor. “He gazes for a moment into the future, so dim, so uncertain, yet so full of promise, promise which has been more than realized.” Photo (April 27, 2008) reprinted courtesy of Alain Edouard Source: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Harvard_statue.jpg Figure F2 University Hall on an early spring evening Reprinted courtesy of Harvard University Harvard College Class of 1957 RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS 60th REUNION COMMITTEE Co-Chairs James L. Joslin John A. Simourian Wallace E. Sisson Members Philip J. Andrews Harvey J. Grasfield Evan Randolph IV Philip J. Arena Peter Gunness Edward J. Rolde Hugh Blair-Smith Alan Harwood George Sadowsky Jeremiah J. Bresnahan Philip C. Haughey David W. Scudder Victor R. Brogna Arthur C. Hodges A. Richard Shain Geoffrey T. Chalmers Newton E. Hyslop, Jr. John A. Simourian Thomas F. Crowley Lawrence A. Joseph Wallace E. Sisson Christopher Crowley James L. Joslin Charles Steedman Alexander Daley Michael D. Kline Robert J. Swartz Peter F. Davis Bruce Macdonald J. Owen Todd John E. Dowling Anthony M. Markella Thomas H. Townsend S. Warren Farrell Neil P. Olken Thomas H. Walsh, Jr. J. Stephen Friedlaender Carl D. Packer Ronald M. Weintraub Evan M. Geilich John Thomas Penniston Philip M. Williams Martin S. -

100 Years/ 100 Reasons to Love the Ed School Now 100 Years

HARVARD ED. HARVARD SPECIAL ISSUE WINTER 2020 WINTER 2020 WINTER 100 YEARS/ 100 REASONS TO LOVE THE ED SCHOOL NOW HED12-FOB-Cover-FINAL.indd 1 12/20/19 1:03 PM Harvard Ed. HARVARD ED. HARVARD SPECIAL ISSUE WINTER 2020 WINTER 2020 Lory Hough, Editor in Chief 100 YEARS/ 100 REASONS TO LOVE THE ED SCHOOL NOW 100 YEARS/ HED12-FOB-Cover-FINAL.indd 1 12/20/19 1:03 PM WINTER 2020 � ISSUE N 165 Editor in Chief Lory Hough [email protected] Creative Direction Modus Operandi Design Patrick Mitchell Melanie deForest Malloy MODUSOP.NET Contributing Writers 100 REASONS Jen Audley, Ed.M.’98 LOVE IS IN THE AIR Emily Boudreau, Ed.M.’19 Timothy Butterfield, Ed.M.’20 This year, the Ed School is celebrating its 100th Tracie Jones Rilda Kissel anniversary. We knew we were going to create a Matt Weber, Ed.M.’11 special theme issue to mark this major milestone, Illustrators but the question was, how should we organize Loogart the information? A deep dive into just the Simone Massoni school’s early history? A straightforward timeline Riccardo Vecchio Rob Wilson approach? None of those options seemed like the right way to tell the story in a way that would Photographers capture not only the school’s beginnings, but also Diana Levine TO LOVE Tony Luong who we are now and who we hope to be in the Walter Smith future — and do it in a way that was fun. However, Copy Editors there was one word that kept coming back to us, a Marin Jorgensen word that might seem odd for a magazine based at Abigail Mieko Vargus a graduate school, but in many ways, the word — POSTMASTER love — makes sense. -

Still Here: Change and Persistence in the Place of the Liberal Arts in American Higher Education

STILL HERE: CHANGE AND PERSISTENCE IN THE PLACE OF THE LIBERAL ARTS IN AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION Robert A. McCaughey Barnard College, Columbia University This essay was commissioned by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation under the auspices of the Mellon Research Forum on the Value of a Liberal Arts Education. © 2019 The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License. To view a copy of the license, please see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The Mellon Foundation encourages distribution of the report. For questions, please write to [email protected]. STILL HERE 1 Preface & Introduction The following essay offers a brief history of the idea and practice of the liberal arts in America. It is based upon a rich body of writings by historians of American higher education. A contributor to that literature, I am here reliant mostly upon the work of others, some my teachers and colleagues, others through their publications. In discussing the recent past, I draw on six decades of personal experience as student, faculty member and erstwhile dean. I welcome the invitation from Mariët Westermann and Eugene Tobin of the Mellon Foundation to undertake this essay, but I have tried to do so in the way John Henry Newman commended “liberal knowledge” to the Catholic gentry of Dublin in The Idea of a University: “That which stands on its own pretensions, which is independent of sequel, expects no complement, refuses to be informed (as it is called) by any end, or absorbed into any art, in order duly to present itself to our contemplation.” [1.] A prefatory word on definitions. -

Charles W. Eliot's Views on Education, Physical Education, and Intercollegiate Athletics

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), Unabridged and Unrevised Charles Breunig

Lawrence University Lux Selections from the Archives University Archives 1994 "A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), unabridged and unrevised Charles Breunig Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/archives_selections Part of the United States History Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Breunig, Charles, ""A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), unabridged and unrevised" (1994). Selections from the Archives. 7. https://lux.lawrence.edu/archives_selections/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selections from the Archives by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "A GREAT AND GOOD WORK": A HISTORY OF LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY (1847-1964) by Charles Breunig Unabridged and Unrevised Version Appleton, Wisconsin 1994 INTRODUCTORY NOTE This manuscript is an unabridged and unrevised version of the book published by the Lawrence University Press in 1994 with the title "A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964). It contains in many places more detail than what appears in the published work. It is organized somewhat differently from the published version with separate chapters on the conservatory of music, the trustees, and athletics. Some, though not all, of the material from these chapters is integrated into the narrative of the published history. An expanded table of contents listing sub-sections within each chapter will enable readers to turn to topics in which they may be particularly interested. -

President Drew Gilpin Faust Experience Boston All Over Again

Debtor Nation USA • Commencement • The Anti-Utopian JULY-AUGUST 2007 • $4.95 President Drew Gilpin Faust experience boston all over again. Come home to the classic style and history of Taj Boston. Revisit your Harvard days with one of our distinctive packages and experience the Boston you once knew. Whether it’s for parents’ weekend, a football game, homecoming or your son or daughter’s first visit, with the prime location on Newbury Street overlooking the Public Garden, you’ll fall in love with Boston once more. for information on specific packages at taj boston, please call 617.536.5700 or contact your travel consultant 15 arlington street t: 1 617.536.5700 1 877.482.5267 [email protected] tajhotels.com/boston india | new york | boston | london | sydney | dubai | mauritius | maldives | sri lanka | bhutan | langkawi Opening Soon: Cape Town, Johannesburg, Doha, Palm Island - Dubai, Phuket JULY-AUGUST 2007 VOLUME 109, NUMBER 6 FEATURES 24 A Scholar in the House Drew Gilpin Faust, the University’s twenty-eighth president by John S. Rosenberg STU ROSNER page 49 32 Le Professeur DEPARTMENTS An anti-utopian, old-school scholar of international relations, Stanley Ho≠mann grasps “the foreignness of foreigners” 2 Cambridge 02138 Craig Lambert Communications from by our readers 11 Right Now 38 Vita: Frederick Law Olmsted Mighty mice have a new Brief life of the first landscape psychoarchitect: kind of muscle, from light to 1822-1903 matter and back, probing professors’ faith STEVE POTTER by Michael Sperber page 20 16A New England Regional Section 40 Debtor Nation A seasonal calendar, New England- America is living on borrowed capital—and perhaps themed neighborhood dining, when adults care for aged parents borrowed time.