A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), Unabridged and Unrevised Charles Breunig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Affairs Series AMBASSADOR WILLIAM T. PRYCE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: September 22, 1997 Copyright 2007 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in California raised in Pennsylvania Wesleyan University and the Fletcher School of Tufts University US Navy Department of Commerce Entered the Foreign Service in 1958 State Department* Fuels Division Economic Bureau/Staff Asst. 1958-19.0 Ara0-1srael policy Assistant Secretary Thomas 2ann Frances Wilson State Department 3atin America Bureau 4ARA6 19.0-19.1 Cu0a-Bay of Pigs 2e7ico City 2e7ico* Consular Officer/Staff Aide 19.1-19.8 Protection cases President 9ennedy:s visit River boundary disputes Relations Government 9ennedy assassination State Department* Staff Assistant 4ARA6 19.8-19.5 Dominican Repu0lic intervention Organization of American States 4OAS6 Am0assador Tapley Bennett State Department* FS1 Russian language training 19.5-19.. 2oscow Soviet Union* Pu0lications Procurement Officer 19..-19.8 1 3enin 3i0raries Travel formalities 9GB Baltic nations Brezhnev Am0assador Thompson Environment Pu0lic contacts Soviet intelligentsia Panama City Panama* Political Officer 19.8-1971 Arnulfo Arias Panama Canal Treaty Canal operation Relations US sovereignty questions Noriega Torrijos Guatemala City Guatemala* Political Counselor 1971-1974 Security Government Elections Environment USA1D 2ilitary Political Parties State Department* Soviet E7change Program* 1974-197. Educational -

Lawrence University (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) at Beloit College (1-1, 0-0

Lawrence University (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) at Beloit College (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) Saturday, September 19, 2015, 1 p.m., Strong Stadium, Beloit, Wisconsin Webcast making his first start, was 23-for-36 ing possession and moved 75 yards A free video webcast is available for 274 yards and three touchdowns. in 12 plays for the game’s first touch- at: http://portal.stretchinternet.com/ Mandich, a senior receiver from Green down. Byrd hit freshman receiver and lawrence/. Bay, had a career-high eight catches Appleton native Cole Erickson with an for 130 yards and a touchdown for the eight-yard touchdown pass to com- The Series Vikings. plete the drive and give Lawrence a Lawrence holds a 58-36-5 edge in The Lawrence defense limited 7-3 lead. a series that dates all the way back to Beloit to 266 yards and made a key The Vikings then put together 1899. This year marks the 100th game stop late in the game to preserve the another long scoring drive early in in the series, which is the second- victory. Linebacker Brandon Taylor the second quarter. Lawrence went longest rivalry for Lawrence. The Vi- paced the Lawrence defense with 14 80 yards in eight plays and Byrd found kings have played 114 games against tackles and two pass breakups. Trevor Spina with a 24-yard touch- Ripon, and that series dates to 1893. Beloit was down by eight but got down pass for a 14-3 Lawrence lead Lawrence has won three of the last an interception on a tipped ball and with 11:53 left in the first half. -

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

Pusey Was Spread Upon the Permanent Records of the Faculty

At a meeting of the FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES on December 14, 2004, the following tribute to the life and service of the late Nathan Marsh Pusey was spread upon the permanent records of the Faculty. NATHAN MARSH PUSEY A.B., 1928; Ph.D. 1937, LL.D., 1972 TWENTY-FOURTH PRESIDENT OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion. It is easy in solitude to live after your own; But the great man is he who, in the midst of the crowd, Keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude. Ralph Waldo Emerson On the afternoon of October 13, 1953, Nathan Marsh Pusey was installed in this room as the twenty-fourth president of Harvard College, inducted into office by Judge Charles Wyzanski, Jr. ’27, president of the Board of Overseers. The new president pledged “To try to keep assembled here the best scholars and teachers that can be found, to work to ensure conditions conducive to their best efforts, and con-stantly to strive for more effective ways to make their activity touch, quicken, and strengthen the intellectual aspirations of succeeding generations of young people.” He concluded with these words: “Harvard is a great intellectual enterprise founded and nourished in great faith. It shall be my purpose, continuing in that faith, to guide it as best I can, so help me God.” Nathan Marsh Pusey was born on April 4, 1907, in Council Bluffs, Iowa. He entered the College in the Class of 1928; in his senior year he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa; and he graduated with a degree in English, magna cum laude. -

Lawrence University

Lawrence University a college of liberal arts & sciences a conservatory of music 1425 undergraduates 165 faculty an engaged and engaging community internationally diverse student-centered changing lives a different kind of university 4 28 Typically atypical Lawrentians 12 College should not be a one-size-fits-all experience. Five stories of how Find the SLUG in this picture. individualized learning changes lives (Hint: It’s easy to find if you know at Lawrence. 10 what you’re looking for.) Go Do you speak Vikes! 19 Lawrentian? 26 Small City 20 Music at Lawrence Big Town 22 Freshman Studies 23 An Engaged Community 30 Life After Lawrence 32 Admission, Scholarship & Financial Aid Björklunden 18 29 33 Lawrence at a Glance Find this bench (and the serenity that comes with it) at Björklunden, Lawrence’s 425-acre A Global Perspective estate on Door County’s Lake Michigan shore. 2 | Lawrence University Lawrence University | 3 The Power of Individualized Learning College should not be a one-size-fits-all experience. Lawrence University believes students learn best when they’re educated as unique individuals — and we exert extraordinary energy making that happen. Nearly two- thirds of the courses we teach at Lawrence have the optimal (and rare) student-to-faculty ratio of 1 to 1. You read that correctly: that’s one student working under the direct guidance of one professor. Through independent study classes, honors projects, studio lessons, internships and Oxford-style tutorials — generally completed junior and senior year — students have abundant -

Lawrence, Volume 95, Number 1, Spring 2014 Lawrence University

Lawrence University Lux Alumni Magazines Communications Spring 2014 Lawrence, Volume 95, Number 1, Spring 2014 Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: http://lux.lawrence.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Liberal Studies Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Lawrence University, "Lawrence, Volume 95, Number 1, Spring 2014" (2014). Alumni Magazines. Book 10. http://lux.lawrence.edu/alumni_magazines/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Communications at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPRING 2014 LAWRENCE LEARNING FOR A LIFETIME L U APPLETON, WISCONSIN L U APPLETON, WISCONSIN LAWRENCE CONTENTS SPRING 2014 VOL. 95, NUMBER 1 1 From the President 2 Life-Changing Learning ART DIRECTORS 6 Posse and the Path to Lifelong Learning Liz Boutelle, Monique Rogers, Tammy Wagner 8 Focusing on Their Futures ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT OF COMMUNICATIONS Craig Gagnon ’76 9 The Lawrence Difference EDITOR 10 The Promise Between the Pages Marti Gillespie 12 A Lifelong Connection to Lawrence VICE PRESIDENT FOR ALUMNI, DEVELOPMENT and COMMUNICATIONS 14 The Power of “I” in a Safe Space Cal Husmann 16 Family Ties PHOTOGRAPHY Liz Boutelle, Ken Cobb Photography, Rachel Crowl, 18 Discovering a Place and a Purpose Craig Gagnon ’76, Tom Gill, Marti Gillespie, Ruth Kmak, Will Melnick ’14, Rick Peterson, Thompson Photo Imagery 22 The Road to the Rhodes -

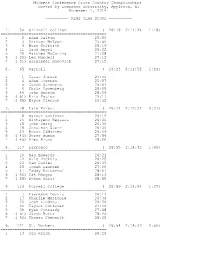

Midwest Conference Cross Country Championships Hosted by Lawrence University, Appleton, WI November 1, 2014 ===MENS TEAM

Midwest Conference Cross Country Championships Hosted by Lawrence University, Appleton, WI November 1, 2014 ========== MENS TEAM SCORE ========== 1. 54 Grinnell College ( 26:19 2:11:34 1:18) ============================================= 1 2 Adam Dalton 25:50 2 3 Anthony McLean 25:55 3 9 Evan Griffith 26:19 4 11 Zach Angel 26:22 5 29 Matthew McCarthy 27:08 6 ( 30) Lex Mundell 27:12 7 ( 31) Alexander Monovich 27:15 2. 65 Carroll ( 26:23 2:11:52 2:29) ============================================= 1 1 Isaac Jordan 25:40 2 4 Adam Joerres 25:57 3 5 Jacob Sundberg 26:01 4 6 Chris Pynenberg 26:05 5 49 Jake Hanson 28:09 6 ( 61) Eric Paulos 29:17 7 ( 65) Bryce Pierson 29:32 3. 78 Lake Forest ( 26:31 2:12:32 0:37) ============================================= 1 8 Mansur Soeleman 26:12 2 14 Sintayehu Regassa 26:26 3 15 John Derry 26:30 4 18 Jonathan Stern 26:35 5 23 Rocco DiMatteo 26:49 6 ( 43) Steve Auman 27:54 7 ( 45) Alec Bruns 28:00 4. 117 Lawrence ( 26:55 2:14:32 1:46) ============================================= 1 10 Max Edwards 26:21 2 12 Kyle Dockery 26:25 3 22 Cam Davies 26:39 4 26 Jonah Laursen 27:00 5 47 Teddy Kortenhof 28:07 6 ( 50) Pat Mangan 28:13 7 ( 55) Ethan Gniot 28:55 5. 119 Cornell College ( 26:59 2:14:54 1:37) ============================================= 1 7 Lawrence Dennis 26:11 2 17 Charlie Mesimore 26:34 3 20 Josh Lindsay 26:36 4 36 Taylor Christen 27:45 5 39 Ryan Conrardy 27:48 6 ( 51) Jacob Butts 28:24 7 ( 52) Thomas Chenault 28:25 6. -

Colleges and Universities Collection Reference Code: Mss-1868

Title: Colleges and Universities Collection Reference Code: Mss-1868 Inclusive Dates: 1867 – ongoing Quantity: 1.4 cu. ft. Location: WC, Sh. 103 Scope and Content: The collection consists of commencement programs, reports, newspaper clippings, catalogs and other ephemera pertaining to post-secondary educational institutions primarily in the Milwaukee area but around the state of Wisconsin as well. Access and Use: No restrictions Language: English Notes: The collection was processed by Steve Daily, April 20, 1996, and added to August 13, 2002, by Kevin Abing. Arrangement: Folder Heading Box # File # Alverno College 1 1 Alverno College 1 2 Beloit College 1 3 Bryant, Stratton & Co.'s Business College 1 4 Business Institute of Milwaukee 1 5 Cardinal Stritch College 1 6 Carroll College 1 7 Carthage College 1 8 Concordia College 1 9 LaCrosse County School of Agriculture and Domestic Economy 1 10 Lakeland College 1 11 Lawrence College 1 12 Layton School of Art and Design 1 13 Marquette Univ. (commencement, dedication, etc.) 1 14 Marquette University (dentistry, law, arts) 1 15 Marquette University (women and Slavic studies) 1 16 Marquette University (annual report, magazine) 1 17 Marquette University (misc. publications) 1 18 Marquette University (journals, bulletins, etc.) 1 19 Mayer's Commercial College 1 20 Milwaukee College 1 21 Milwaukee College 1 22 Milwaukee Downer College 1 22A Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design 1 23 Milwaukee Law School 1 24 Milwaukee Medical College 1 25 Milwaukee School of Engineering 1 26 Milwaukee School of Engineering 1 27 Mount Mary College 2 28 Rheude's Business College and Drafting School 2 29 Ripon College 2 30 Sacred Heart School of Theology 2 31 St. -

Anthony Mann, “How 'Poor Country Boys' Became Boston Brahmins: the Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-Bellum

Anthony Mann, “How ‘poor country boys’ became Boston Brahmins: The Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-bellum Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 31, No. 1 (Winter 2003). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj. Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 How ‘poor country boys’ became Boston Brahmins: The Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-bellum Massachusetts1 By Anthony Mann The promise of social mobility was a central cultural tenet of the northern American states during the nineteenth century. The stories of those who raised themselves from obscure and humble origins to positions of wealth and status, whilst retaining a sufficiency of Protestant social responsibility, were widely distributed and well received amongst a people daily experiencing the personal instabilities of the market revolution.2 Two families which represented the ideal of social mobility 1 A version of this essay was first read at the conference of the British Association for American Studies, Birmingham, and April 1997. My thanks to Colin Bonwick, Louis Billington, Martin Crawford and Phillip Taylor who have advised since then. -

Course Catalog 2009-10

Course Catalog 2009-10 L U APPLETON, WISCONSIN L U APPLETON, WISCONSIN CONTENTS About Lawrence 8 Mission 8 Educational philosophy 8 Lawrence in the community 8 History 9 Presidents of the college 11 The Liberal Arts Education 12 Liberal learning 12 A Lawrence education 13 A residential education 13 The Campus Community 14 Academic and campus life services 14 The campus and campus life 15 Planning an Academic Program 23 The structure of the curriculum 24 Postgraduate considerations 28 Degree and General Education Requirements 31 Residence requirements 31 Bachelor of Arts degree 31 Bachelor of Music degree 33 B A and B Mus double-degree program 35 Cooperative degree programs 37 Engineering 38 Forestry and environmental studies 38 Occupational therapy 39 Courses of Study 40 Anthropology 40 Archaeology (see Anthropology) Art and Art History 52 Studio Art 52 Art History 60 Biochemistry 68 Biology 75 Biomedical Ethics 89 Business (see postgraduate considerations) Chemistry 98 Chinese and Japanese 109 Classics 116 Cognitive Science 126 2 CONTENTS Computer Science 132 East Asian Studies 138 Economics 146 Education 158 English 171 Environmental Studies 183 Ethnic Studies 200 Film Studies 212 French and Francophone Studies 220 Freshman Studies 230 Gender Studies 233 Geology 245 German 256 Government 269 History 283 International Studies 306 Japanese (see Chinese and Japanese) Latin American Studies 308 Law (see postgraduate considerations) Linguistics 313 Mathematics 322 Medicine (see postgraduate considerations) Music 333 Interdisciplinary Major -

Cotton Whigs and Union: the Textile Manufacturers of Massachusetts and the Coming of the Civil

././ // 518CB 18CB8B:5D'-) '-, CCB8B:HBCB. 8BH89HC889H 8B:9CBC8 4 CBBC5C82B /CCB6B D.&&:8B:B&('))&') BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUA'rE SCHO OL \ t .{I',, D ( : ( I ( Dissertation COTI'ON WillGS AND UHION: Tii--:E OF MASSA.GHIJS.E'T'l1S Al'ID THE ,GOMING OF THE CIVIL WAR . By Thomas Henry O'Connor (A.B., Boston College, 1949; A. M., Boston College, 1950) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1958 Approved by First Reader , " . ,, Professor. .of . Histor;. • • .... • • • • • • Second Reader • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Professor of Hist ory TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE Introduction. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • i I . Lords of the Loom • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 I I. Broadcloth and '.J:; otton • • • • • • • • • • • 34 III. Got ton Versus .Conscience. • • • • • • • • • • 69 I V. Gentleman's Agreement • • • • • • • • • • • • 105 v. Awake t he Sleep ing Ti ger. • • • • • • • • • • 135 VI. The Eleventh Hour • • • • • • • • • • 177 Conclusion. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 225 Bi b1iography. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 229 Abstract. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 245 Vita. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 248 INTRODUCTION In 1941J Philip FonerJ in his Business and SlaveryJ made an appeal for a more detailed study of the Northern business man and his reaction to the coming of the Civil War. Countering the popular interpretation that the war was the product of two conflicting economic systemsJ Professor Foner presented his own observations regarding the concerted efforts of the New York financial interests to Check any and all move- ments which tended to precipitate an intersectional struggle. The documented reactions of this particular group of Nor t h ern business men could not be explained in terms of an over- simplified economic interpretation of the Civil War, and for this reason Professor Foner pointed to the need for more intensive research into the economic sources and materials of the ante-bellum period. -

The American Council on Education's 122 Original Member Institutions

American Council on Education THE AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION’S 122 ORIGINAL MEMBER INSTITUTIONS ALABAMA ILLINOIS Alabama Polytechnic Institute De Paul University now Auburn University Eureka College James Millikin University CALIFORNIA now Millikin University California Institute of Technology Knox College Leland Stanford Junior University Northwestern University Mills College Rockford College Occidental College University of Chicago Pomona College University of Illinois University of California YMCA College of Chicago University of Southern California now Roosevelt University COLORADO INDIANA Colorado College Butler College Colorado State Teachers’ College DePauw University now University of Northern Colorado Rose Polytechnic Institute University of Colorado University of Notre Dame CONNECTICUT IOWA Connecticut College Cornell College Wesleyan University Grinnell College Yale University Iowa State Teachers College now University of Northern Iowa DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Luther College Catholic University of America Union College of Iowa Upper Iowa University GEORGIA Brenau College ACE Original Member Institutions KANSAS MINNESOTA Baker University Carleton College Washburn College College of St. Catherine College of St. Olaf KENTUCKY College of St. Teresa Centre College College of St. Thomas Georgetown College Hamline University University of Kentucky Macalester College University of Minnesota MAINE Bowdoin College MISSOURI Kirksville State Teachers’ College MARYLAND now Truman State University Goucher College Southeast Missouri State