Painterly Style in Robert Bresson's Au Hasard Balthazar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

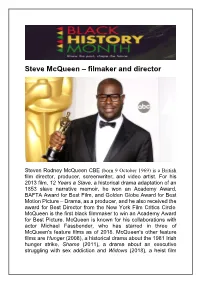

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Une Année Studieuse

Extrait de la publication DU MÊME AUTEUR Aux Éditions Gallimard DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES MON BEAU NAVIRE (Folio no 2292) MARIMÉ (Folio no 2514) CANINES (Folio no 2761) HYMNES À L’AMOUR (Folio no 3036) UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS. Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française 1998 (Folio no 3358) AUX QUATRE COINS DU MONDE (Folio no 3770) SEPT GARÇONS (Folio no 3981) JE M’APPELLE ÉLISABETH (Folio no 4270) L’ÎLE. Nouvelle extraite du recueil DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES (Folio 2 € no 4674) JEUNE FILLE (Folio no 4722) MON ENFANT DE BERLIN (Folio no 5197) Extrait de la publication une année studieuse Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication ANNE WIAZEMSKY UNE ANNÉE STUDIEUSE roman GALLIMARD © Éditions Gallimard, 2012. Extrait de la publication À Florence Malraux Extrait de la publication Un jour de juin 1966, j’écrivis une courte lettre à Jean-Luc Godard adressée aux Cahiers du Cinéma, 5 rue Clément-Marot, Paris 8e. Je lui disais avoir beaucoup aimé son dernier i lm, Masculin Féminin. Je lui disais encore que j’aimais l’homme qui était derrière, que je l’aimais, lui. J’avais agi sans réaliser la portée de certains mots, après une conversation avec Ghislain Cloquet, rencontré lors du tournage d’Au hasard Balthazar de Robert Bresson. Nous étions demeurés amis, et Ghislain m’avait invitée la veille à déjeuner. C’était un dimanche, nous avions du temps devant nous et nous étions allés nous promener en Normandie. À un moment, je lui parlai de Jean-Luc Godard, de mes regrets au souvenir de trois rencontres « ratées ». -

El Último Cine

Cartel alemán de Estambul 65 (Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, 1965). Bilbao (Bigas Luna, 1978) SuscripciónSuscripción a la a alertala alerta del del programa programa mensual mensual del del cine cine Doré Doré en: en: http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO Ciclos en preparación: Marzo: William Wellman (y II) CiclosAño enDual preparación: España-Japón 3XDOC Febrero:Ellas crean: Nueve cineastas argentinas Muestra de cine filipino (y II) MuestraRecuerdo de cinede: Jesúsbúlgaro Franco, Alfredo Landa, Lolita Sevilla … CasaCentenario Asia presenta: de Rafael ‘El últimoGil (y II) cine iraní’ RecuerdoJirí Menzel de Maureen O´Hara Mikhail Romm Jirí Menzel Brian de Palma Alberto Lattuada Alberto Lattuada Luc Moullet GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE ENERO 2016 Centenario de Harold Lloyd Robert Bresson Recuerdo de Vicente Aranda Costa-Gavras Muestra de cine filipino Muestra de cine palestino (y II) Muestra de cine rumano (y II) Costa-Gavras Mike de Leon rodando Itim (1976) Agradecimientos enero 2016: A Contracorriente Films, Barcelona; Antonio Isasi Jr., Barcelona; Cinemateca Portuguesa, Lisboa; Film Development Council of the Philippines (Briccio Santos, presidente, y Teodoro Granados, director ejecutivo), Makati; Flat Cinema, Madrid; Gaumont, Harold Lloyd Entertainment, Inc. (Sara Juárez), Los Ángeles; Instituto Cultural Rumano de Madrid (Ioana Anghel, Ovidiu Miron); Lola Films, Madrid; Multivideo S.L, Madrid; Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum (Regina Schlagnitweit ), Viena; Plataforma de Divulgación UCM (Ricardo Jimeno y José Antonio Jiménez de las Heras), Madrid; Tamasa Distribu- tion, París; Universal Pictures; Video Mercury, Madrid; Warner Bros. Pictures int. -

Directing the Narrative Shot Design

DIRECTING THE NARRATIVE and SHOT DESIGN The Art and Craft of Directing by Lubomir Kocka Series in Cinema and Culture © Lubomir Kocka 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933406 ISBN: 978-1-62273-288-3 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. CONTENTS PREFACE v PART I: DIRECTORIAL CONCEPTS 1 CHAPTER 1: DIRECTOR 1 CHAPTER 2: VISUAL CONCEPT 9 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPT OF VISUAL UNITS 23 CHAPTER 4: MANIPULATING FILM TIME 37 CHAPTER 5: CONTROLLING SPACE 43 CHAPTER 6: BLOCKING STRATEGIES 59 CHAPTER 7: MULTIPLE-CHARACTER SCENE 79 CHAPTER 8: DEMYSTIFYING THE 180-DEGREE RULE – CROSSING THE LINE 91 CHAPTER 9: CONCEPT OF CHARACTER PERSPECTIVE 119 CHAPTER 10: CONCEPT OF STORYTELLER’S PERSPECTIVE 187 CHAPTER 11: EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION/ EMOTIONAL DESIGN 193 CHAPTER 12: PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL REGULARITIES IN LEFT-RIGHT/RIGHT-LEFT ORIENTATION 199 CHAPTER 13: DIRECTORIAL-DRAMATURGICAL ANALYSIS 229 CHAPTER 14: DIRECTOR’S BOOK 237 CHAPTER 15: PREVISUALIZATION 249 PART II: STUDIOS – DIRECTING EXERCISES 253 CHAPTER 16: I. -

Pdf-Collections-.Pdf

1 Directors p.3 Thematic Collections p.21 Charles Chaplin • Abbas Kiarostami p.4/5 Highlights from Lobster Films p.22 François Truffaut • David Lynch p.6/7 The RKO Collection p.23 Robert Bresson • Krzysztof Kieslowski p.8/9 The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew p.24 D.W. Griffith • Sergei Eisenstein p.10/11 Yiddish Collection p.25 Olivier Assayas • Alain Resnais p.12/13 Themes p.26 Jia Zhangke • Gus Van Sant p.14/15 — Michael Haneke • Xavier Dolan p.16/17 Buster Keaton • Claude Chabrol p.18/19 Actors p.31 Directors CHARLES CHAPLIN THE COMPLETE COLLECTION AVAILABLE IN 2K “A sort of Adam, from whom we are all descended...there were two aspects of — his personality: the vagabond, but also the solitary aristocrat, the prophet, the The Kid • Modern Times • A King in New York • City Lights • The Circus priest and the poet” The Gold Rush • Monsieur Verdoux • The Great Dictator • Limelight FEDERICO FELLINI A Woman of Paris • The Chaplin Revue — Also available: short films from the First National and Keystone collections (in 2k and HD respectively) • Documentaries Charles Chaplin: the Legend of a Century (90’ & 2 x 45’) • Chaplin Today series (10 x 26’) • Charlie Chaplin’s ABC (34’) 4 ABBas KIAROSTAMI NEWLY RESTORED In 2K OR 4K “Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema” — MARTIN SCORSESE Like Someone in Love (in 2k) • Certified Copy (in 2k) • Taste of Cherry (soon in 4k) Shirin (in 2k) • The Wind Will Carry Us (soon in 4k) • Through the Olive Trees (soon in 4k) Ten & 10 on Ten (soon in 4k) • Five (soon in 2k) • ABC Africa (soon -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

22—25 Juin 2017

22—25 juin 2017 TOULOUSE MÉTROPOLE 13e festival international de littérature LE MARATHON DES MOTS SOMMAIRE Direction - Programmation : Serge Roué Direction déléguée : Dalia Hassan Coordination générale : Noémie de La Soujeole assistée de Marion Lemmet Communication : Édouard de Cazes ÉDITOS assisté de Laure Perrinet Service de presse : Shanaz Barday Olivier POIVRE DʼARVOR ........................................ 5 (Faits & Gestes - 01 53 34 64 84) Jean-Luc MOUDENC ............................................... 5 assistée de Camille Carnevale Carole DELGA ......................................................... 7 Évènements spéciaux : Elsa Viguier Coordination des bénévoles : Charlotte Barbe Philippe WAHL ......................................................... 7 assistée de Nelly Frisicaro Serge ROUÉ | Dalia HASSAN .................................. 9 Collaboration artistique : Patrick Autréaux, Laurent Belvèze, Jean-Jacques Cubaynes (Lettres occitanes) et Guillaume Poix Coordination technique : Jean-Pierre Siguier (SED Spectacles) PROGRAMME Jeudi 22 juin ............................................................................................................ 11 TOULOUSE, LE MARATHON DU LIVRE Vendredi 23 juin ................................................................................................. 23 Association Loi 1901 (Siret 481 981 165 000 30 - Code APE : 8230Z Samedi 24 juin ..................................................................................................... 43 Licences n°2-1052821 et n° 3-1052822) Dimanche -

Insubmersible Godard Jean Beaulieu

Document generated on 09/26/2021 5:23 p.m. Séquences : la revue de cinéma Le redoutable Insubmersible Godard Jean Beaulieu Abdellatif Kechiche, Mektoub My Love : Canto Uno Number 314, June 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/89068ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Beaulieu, J. (2018). Review of [Le redoutable : insubmersible Godard]. Séquences : la revue de cinéma, (314), 31–31. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ MICHEL HAZANAVICIUS Le redoutable Insubmersible Godard JEAN BEAULIEU Un pitch improbable. Michel Hazanavicius s’est liés à son modèle (cartons-titres géants intercalés montré plutôt gonflé de proposer à ses producteurs dans une scène, passage alternatif d’un tirage positif/ une comédie biographique ayant comme principal négatif à la Alphaville, travelling longeant le corps protagoniste l’un des monstres sacrés du cinéma dénudé de Stacy Martin calqué sur celui de Raoul moderne, Jean-Luc Godard, à un moment charnière Coutard filmant BB dans Le mépris, la voix-off de de sa carrière où, après le tournage de La Chinoise, Michel Subor, une musique de Martial Solal, etc.). -

Jeune Fille. Anne Wiazemsky, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 2007, 217 P. Robert Daudelin

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:56 24 images Jeune fille. Anne Wiazemsky, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 2007, 217 p. Robert Daudelin Le pays d’Arthur Lamothe Numéro 132, juin–juillet 2007 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/13261ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Daudelin, R. (2007). Compte rendu de [Jeune fille. Anne Wiazemsky, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 2007, 217 p.] 24 images, (132), 59–59. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2007 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ CIN-ECRITS Lecteur : Robert Daudelin JEUNE FILLE Anne Wiazemsky, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 2007, 217 p. Au hasard Balthazar 'est un «roman». Du moins, c'est ce « drôle de zigoto ». Anne n'est donc pas ce qu'annonce la page titre du plus comédienne - un mot et un métier dont s'ac C récent livre d'Anne Wiazemsky. commode très mal le cinéaste - mais modèle Pourtant les personnages sont bien réels : pour un cinéaste qui, c'est le moins qu'on Robert Bresson est bien le grand cinéaste puisse dire, sait très bien où il veut aller.