Au Hazard Balthazar 1966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermon, January 3, 2016 2 Christmas Jeremiah 31:7-14, Psalm 84, Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19, Matthew 2:1-12 by the Rev. Dr. Kim Mcnamara

Sermon, January 3, 2016 2 Christmas Jeremiah 31:7-14, Psalm 84, Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19, Matthew 2:1-12 By The Rev. Dr. Kim McNamara As I was taking down and putting away our Christmas decorations on New Year’s Day, my dear husband, John, teased me just a bit about my ritualistic behavior. In many ways, he is right. Christmas, for me, is guided by traditional rituals and symbols. Because I live a very busy life and work in an academic setting divided up into quarterly cycles, the rituals I have marked on the calendar help me to make sure I do everything I want to do in the short amount of time I have to do it in. Along with the rituals, the symbols serve as mental touchstones for me; focusing my attention, my thoughts, my reflections, my memories, and my prayers, on the many meanings of Christmas. My own Christmas rituals start in Advent with two traditional symbols of Christmas, the advent wreath and the nativity. On my birthday, which is exactly two weeks before Christmas, I buy a Christmas tree. (I am not sure what the symbolism is, but it sure is pretty.) As I grade final exams and projects for my students, I reward myself for getting through piles and hours of grading by taking breaks every now and then to decorate for Christmas. According to my ritual schedule, grades and Christmas decorations have to be completed by December 18. I then have two weeks to savor and reflect upon the wonder, beauty, and love of Christmas. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Bulletincoverpage 2021.Pub

St. Joseph Catholic Church 1294 Makawao Avenue, Makawao, HI 96768 SCHEDULE OF SERVICES CONTACT INFORMATION DAILY MASS: Monday-Friday…...7 a.m. Office: (808) 572-7652 Saturday Sunday Vigil 5:00 p.m. Fax: (808) 573-2278 Sunday Masses: 7:00 a.m., 9:00 a.m. & 5:00 p.m. Website: www.sjcmaui.org Confessions: By appointment only on Tuesday, Thurs- Email: day, & Saturday from 9a.m. - 11 a.m. at the rectory. Call [email protected] 572-7652 to schedule your appointment. PARISH MISSION: St. Joseph Church Parish is a faith community in Makawao, Maui. We are dedicated to the call of God, to support the Diocese of Honolulu in its mission, to celebrate the Eucharist, and to commit and make Jesus present in our lives. ST. JOSEPH CHURCH STAFF Administrator: Rev. Michael Tolentino Deacon Patrick Constantino Business Administrator: Donna Pico EARLY LEARNING CENTER Director: Helen Souza; 572-6235 Office Clerk: Sheri Harris Teachers: Renette Koa, Cassandra Comer CHURCH COMMITTEES Pastoral Council: Christine AhPuck; 463-1585 Finance Committee: Ernest Rezents; 572-8663 Church Building/Master Planning: Jordan Santos; 572-9768 Stewardship Committee: Arsinia Anderson; 572-8290 & Helen Souza; 572-5142 CHURCH FUNDRAISING Thrift Shop: Joslyn Minobe: 572-7652 Sweetbread: Jackie Souza: 573-8927 St. Joseph Feast: Donna Pico: 572-7652 CHURCH MINISTRIES WORSHIP MINISTRY Altar Servers: Helen Souza: 572-5142 Arts & Environment: Berna Gentry: 385-3442 Lectors: Erica Gorman; 280-9687 Extraordinary Minister of Holy Communion/Sick & Homebound: Jamie Balthazar; 572-6403 -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

ENG 494: the Essay-Film's Recycling Of

Nandini Chandra, Study Abroad Application Location Specific Course Proposal The Essay-Film’s Recycling of “Waste”: Lessons from the Left Bank *ENG 494: Study Abroad (3) The essay film shuns the mimetic mode, opting to construct a reality rather than reproduce one. Some of its signature tools in this project are: experimental montage techniques, recycling of still photographs, and the use of found footage to immerse the viewer in an alternative and yet uncannily plausible reality. Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnes Varda are three giants of this genre who shaped this playful filmic language in France. The essay-film is their paradoxical contribution to crafting a collective experience out of the minutiae of individual self-expressions. Our course will focus particularly on this trio of directors’ self-reflexive and heretical relationship with the theme of “waste”— industrial, cultural and human—which forms a central preoccupation in their films. Many of these films use the trope of travel to show wastelands created by the history of capitalist wars and colonialism. We will examine the diverse ways in which the essay-film alters our understanding of “waste” and turns it into something mysteriously productive. This in turn leads us to the question of the “surplus population”—those thrown out of the circuits of capitalist production and left to fend for themselves—as a source of potentially utopian possibilities. Capitalism’s well-known “creative destruction” is ironically paralleled by these films’ focus on the productivity of waste products, and the creative powers of capitalism’s outcastes. 1. The course will historiciZe the critical-lyrical practice of the essay-film, looking at the films themselves as well as key scholarship on essay-films. -

OIL MILL GAZETTEER Official Organ of the National Oil Mill Superintendents’ Association

OIL MILL GAZETTEER Official Organ of the National Oil Mill Superintendents’ Association. VOL. X V Ii., NO. 10. WHARTON, TEXAS, APRIL, 1916. PRICE TEN CENTS From Secretary-Treasurer Morris It is unnecessary for me to go into details vention, and certainly hope I will succeed much concerning our next convention, for President better. Leonard’s letter in the March issue was to the Let everybody boost for the convention and point and brings out in full everything connect be sure to be on hand yourself. Yours to ed with our next meeting. However, I want to serve, F. P. MORRIS, impress upon the minds of all members that in Secretary-Treasurer. order to succeed as we have planned, you must * * * attend. Let’s make this our banner meeting BIG FIRE LOSS AT TYLER year. I have letters from superintendents from California to North Carolina expressing their Tyler, Texas, March 17.— The Tyler Oil desire to be there, and if nothing prevents, you Company and the Tyler Ice Company suffered a will see them. Now then, let’s all who live, fire loss last night of between $25,000 and closer be on hand. The meeting has been ad $30,000. The oil company lost its big seed house, vertised throughout all cotton growing states, in which there was no seed, and its hull house, and I will continue to do so from now until the in which was stored a large quantity of hulls. convention meets. If President Leonard and The damage to the walls of the large mill build myself, assisted very ably by our never tiring ing will amount to several thousand dollars. -

Une Année Studieuse

Extrait de la publication DU MÊME AUTEUR Aux Éditions Gallimard DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES MON BEAU NAVIRE (Folio no 2292) MARIMÉ (Folio no 2514) CANINES (Folio no 2761) HYMNES À L’AMOUR (Folio no 3036) UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS. Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française 1998 (Folio no 3358) AUX QUATRE COINS DU MONDE (Folio no 3770) SEPT GARÇONS (Folio no 3981) JE M’APPELLE ÉLISABETH (Folio no 4270) L’ÎLE. Nouvelle extraite du recueil DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES (Folio 2 € no 4674) JEUNE FILLE (Folio no 4722) MON ENFANT DE BERLIN (Folio no 5197) Extrait de la publication une année studieuse Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication ANNE WIAZEMSKY UNE ANNÉE STUDIEUSE roman GALLIMARD © Éditions Gallimard, 2012. Extrait de la publication À Florence Malraux Extrait de la publication Un jour de juin 1966, j’écrivis une courte lettre à Jean-Luc Godard adressée aux Cahiers du Cinéma, 5 rue Clément-Marot, Paris 8e. Je lui disais avoir beaucoup aimé son dernier i lm, Masculin Féminin. Je lui disais encore que j’aimais l’homme qui était derrière, que je l’aimais, lui. J’avais agi sans réaliser la portée de certains mots, après une conversation avec Ghislain Cloquet, rencontré lors du tournage d’Au hasard Balthazar de Robert Bresson. Nous étions demeurés amis, et Ghislain m’avait invitée la veille à déjeuner. C’était un dimanche, nous avions du temps devant nous et nous étions allés nous promener en Normandie. À un moment, je lui parlai de Jean-Luc Godard, de mes regrets au souvenir de trois rencontres « ratées ». -

Filmar As Sensações

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM FILOSOFIA Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson São Paulo 2012 Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson Tese apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em Filosofia do Departamento de Filosofia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Filosofia sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Luiz Fernando B. Franklin de Matos. São Paulo 2012 Ao pequeno Hiro, grande herói, dedico esse trabalho. “Tão longe que se vá, tão alto que se suba, é preciso começar por um simples passo.” Shitao. Agradecimentos À CAPES, pela bolsa concedida. À Marie, Maria Helena, Geni e a todo o pessoal da secretaria, pela eficiência e por todo o apoio. Aos professores Ricardo Fabbrini e Vladimir Safatle, pela participação na banca de qualificação. Ao professor Franklin de Matos, meu orientador e mestre de todas as horas. A Jorge Luiz M. Villela, pelo incentivo constante e pelo abstract. A José Henrique N. Macedo, aquele que ama o cinema. Ao Dr. Ricardo Zanetti e equipe, a quem devo a vida de minha esposa e de meu filho. Aos meus familiares, por tudo e sempre. RESUMO TAKAYAMA, L. R. Filmar as sensações: cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson. 2012. 186 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas. Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2012. -

WILD Grasscert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES)

WILD GRASS Cert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES) A film directed by Alain Resnais Produced by Jean‐Louis Livi A New Wave Films release Sabine AZÉMA André DUSSOLLIER Anne CONSIGNY Mathieu AMALRIC Emmanuelle DEVOS Michel VUILLERMOZ Edouard BAER France/Italy 2009 / 105 minutes / Colour / Scope / Dolby Digital / English Subtitles UK Release date: 18th June 2010 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐Mail: [email protected] or FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films – [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 www.newwavefilms.co.uk WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) SYNOPSIS A wallet lost and found opens the door ‐ just a crack ‐ to romantic adventure for Georges (André Dussollier) and Marguerite (Sabine Azéma). After examining the ID papers of the owner, it’s not a simple matter for Georges to hand in the red wallet he found to the police. Nor can Marguerite retrieve her wallet without being piqued with curiosity about who it was that found it. As they navigate the social protocols of giving and acknowledging thanks, turbulence enters their otherwise everyday lives... The new film by Alain Resnais, Wild Grass, is based on the novel L’Incident by Christian Gailly. Full details on www.newwavefilms.co.uk 2 WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) CREW Director Alain Resnais Producer Jean‐Louis Livi Executive Producer Julie Salvador Coproducer Valerio De Paolis Screenwriters Alex Réval Laurent Herbiet Based on the novel L’Incident -

BAM/PFA Program Guide

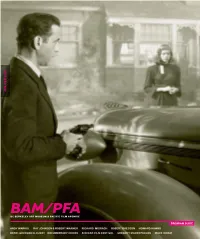

B 2012 B E N/F A J UC BERKELEY ART MUSEum & PacIFIC FILM ARCHIVE PROGRAM GUIDE AnDY WARHOL RAY JOHNSON & ROBERT WARNER RICHARD MISRACH rOBERT BRESSON hOWARD HAWKS HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOt dOCUMENTARY VOICES aFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL GREGORY MARKOPOULOS mARK ISHAM BAM/PFA EXHIBITIONS & FILM SERIES The ReaDinG room P. 4 ANDY Warhol: PolaroiDS / MATRIX 240 P. 5 Tables OF Content: Ray Johnson anD Robert Warner Bob Box ArchiVE / MATRIX 241 P. 6 Abstract Expressionisms: PaintinGS anD DrawinGS from the collection P. 7 Himalayan PilGrimaGE: Journey to the LanD of Snows P. 8 SilKE Otto-Knapp: A liGht in the moon / MATRIX 239 P. 8 Sun WorKS P. 9 1 1991: The OAKlanD-BerKeley Fire Aftermath, PhotoGraphs by RicharD Misrach P. 9 RicharD Misrach: PhotoGraphs from the Collection State of MinD: New California Art circa 1970 P. 10 THOM FaulDers: BAMscape Henri-GeorGes ClouZot: The Cinema of Disenchantment P. 12 Film 50: History of Cinema, Film anD the Other Arts P. 14 BehinD the Scenes: The Art anD Craft of Cinema Composer MARK Isham P. 15 African film festiVal 2012 P. 16 ScreenaGers: 14th Annual Bay Area HIGH School Film anD ViDeo FestiVal P. 17 HowarD HawKS: The Measure of Man P. 18 Austere Perfectionism: The Films of Robert Bresson P. 21 Documentary Voices P. 24 SeconDS of Eternity: The Films of GreGory J. MarKopoulos P. 25 DiZZY HeiGhts: Silent Cinema anD Life in the Air P. 26 Cover GET MORE The Big Sleep, 3.13.12. See Hawks series, p. 18. Want the latest program updates and event reminders in your inbox? Sign up to receive our monthly e-newsletter, weekly film update, 1. -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

The Austere Cinema Of

'SAtti:4110--*. Control and Redemption The Austere Cinema of The Bresson Project is one of the most Jean—Luc Godard says, "Robert Bresson is comprehensive retrospectives undertaken by French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian Cinematheque Ontario. Robert Bresson, now novel and Mozart German music." Yet few of in his early 90s, is described by many critics as Bresson's films are available in any form in the world's greatest living filmmaker. Starting North America and little has been written on with what he considers to be his first film, Les him in English. Accompanying the new series Anges du peche in 1943, Bresson made 13 of 35mm prints by Cinematheque Ontario feature—length films in 40 years. (An earlier for The Bresson Project, is Robert Bresson, a comedy, Les Affaires publiques, filmed in 1935, 600—page collection of essays in English from was considered lost until its discovery in 1987 writer/critics such as Andre Bazin, Susan at La Cinematheque Francaise.) Although Sontag, Alberto Moravia, Jonathan Rosenbaum perhaps not as prodigious as the output from and Rene Predal. Following its debut showing other directors, Bresson's body of work, with at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto last fall, all its passionate austerity, has had an The Bresson Project travels to more than an inestimable influence on the history of cinema. dozen centres across North America this year. T ravelling across central France this route more times than I can recall, toward Lyon, as you near Bromont- more often than not on the way to Lamothe, the spare hillside village Robert the Cannes Film Festival.