Directing the Narrative Shot Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

Over the Past Ten Years, Good Machine, a New York-Based

MoMA | press | Releases | 2001 | Good Marchine: Tenth Anniversary Page 1 of 4 For Immediate Release February 2001 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART TO CELEBRATE TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF GOOD MACHINE, NEW YORK-BASED PRODUCTION COMPANY Good Machine: Tenth Anniversary February 13-23, 2001 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1 Over the past ten years, Good Machine, a New York-based production company helmed by Ted Hope, David Linde and James Schamus, has become one of the major forces in independent film culture worldwide. Dedicated to the work of emerging, innovative filmmakers, Good Machine has produced or co-produced films by, among others, Ang Lee, Todd Solondz, Nicole Holofcener, Ed Burns, Cheryl Dunye and Hal Hartley. Beginning with Tui Shou (Pushing Hands) (1992), the first collaboration between Good Machine and director Ang Lee, The Museum of Modern Art presents eight feature films and five shorts from February 13 through 23, 2001 at the Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1. "Good Machine proves that audiences do want to be entertained intelligently and engaged substantively," remarks Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film and Video, who organized the series. "Their achievements are reflected in this Tenth Anniversary series and are, in large part, due to Good Machine's collaborations with filmmakers and its respect for the creative process." In addition to producing and co-producing films, Good Machine has gone on to establish an international sales company involved in distributing diverse and unusual works such as Joan Chen's Xiu Xiu: The Sent-Down Girl (1998) and Lars Von Trier's Dancer in the Dark (2000). -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Offscreen Space from Cinema and Sculpture to Photography, Poetry, and Narrative

Offscreen Space From Cinema and Sculpture to Photography, Poetry, and Narrative Thomas Harrison This essay aims to explore formal limits of artistic idioms and some manners in which they are put to positive semantic use. With the help of a term borrowed from film studies, I will argue that many, if not most, artworks activate relations between spaces directly embodied by their signs (recognizable shapes in the visual arts, for example, or words in written texts) and spaces indirectly conveyed by contexts, associations, or imaginings produced outside the borders of those perceptible forms in the mind of a reader or spectator. Aspects of offscreen space are marked by the visual, aural, or conceptual perimeters of what a work actually presents onscreen, amplifying its voice or points of reference and occasionally even making the work seem somewhat partial or incomplete.1 More concrete offscreen spaces pertain to the cultures of a work’s production and reception, subject to variable methodologies of interpretation. In both cases, components of a work’s meaning are construed to lie outside its formal articulation, beyond its explicitly pictured purview, in questions or matters that it conjures up. Some aspects of the off seem primarily semiotic in nature, involving connotations or lacunae in the work’s conventions or system of signs; others appear to be functions of the material and cultural humus from which and to which a work is addressed. Either way, the offscreen spaces activated by a work of art are as constructive of the significance we attribute to it as the lines and tones and colors and words of which it is composed. -

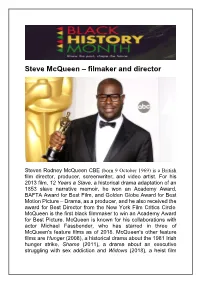

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

Evening Filmmaking Workshop

FILMM NG A I K N I E N V G E P R K O O DU BO CTION HAND April 2010 NEW YORK FILM ACADEMY 100 East 17th Street Tel: 212-674-4300 Email: [email protected] New York, NY 10003 Fax: 212-477-1414 www.nyfa.edu CLASSES Direcotr’s Craft Hands-on Camera and Lighting Director’s Craft serves as the spine of the workshop, Beginning on day one, this is a no-nonsense introducing students to the language and practice camera class in which students learn fundamental of filmmaking. Through a combination of hands- skills in the art of cinematography with the 16mm on exercises, screenings, and demonstrations, Arriflex-S, the Lowel VIP Lighting Kit and its students learn the fundamental directing skills accessories. Students shoot and screen tests for needed to create a succinct and moving film. focus, exposure, lens perspective, film latitude, This class prepares students for each of their slow/fast motion, contrast, and lighting during their film projects and is the venue for screening and first week of class. critiquing their work throughout the course. Production Workshop Writing Production Workshop gives students the The writing portion of the filmmaking course opportunity to learn which techniques will help adheres to the philosophy that good directing them express their ideas most effectively. cannot occur without a well-written script. The This class is designed to demystify the craft of course is designed to build a fundamental filmmaking through in-class exercises shot on understanding of dramatic structure, which is film under the supervision of the instructor. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Cci3 Literature 1421 Projective Identification

CCI3 LITERATURE PROJECTIVE IDENTIFICATION WITH THE ROMA PEOPLE IN BALKAN FILMS Puskás-Bajkó Albina, PhD Student, ”Petru Maior” University of Tîrgu Mureș Abstract: In the cinema of the Balkans Roma people are present at every step. As these films were not directed by Roma specialists, one has the tendency to ask the question: how true are these figures to the real Roma nature and behaviour? And very important: what can we account this ongoing interest in Gipsy culture and life for? Is it curiosity about what seems to otherwise be despised by people or could it possibly be the so-called “projective identification”, an expression extensively used by Jacques Lacan in psychoanalysis? The figure of the Gipsy is omnipresent in the history of Balkan cinema. The first ever Balkan film, shown in foreign countries too was about them: In Serbia: A Gypsy Marriage (1911), the first ever Gypsy film to enter and win an international film festival was from the former Yugoslavia: I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967), directed by Aleksander Petrovic. It won the “Grand Prix Special”. The image of the Gipsy was, however presented by the non-Roma film-directors in these films. “Rather than being given the chance to portray themselves, the Romani people have routinely been depicted by others. The persistent cinematic interest in “Gypsies” has repeatedly raised questions of authenticity versus stylization, and of patronization and exoticization, in a context marked by overwhelming ignorance of the true nature of Romani culture and heritage. ” Dina Iordanova, Cinematic Images of Romanies, in Framework, Introduction, no. 6 Keywords: Projection, Balkans, Romani, film, foreign, mentality. -

Bastille Day Parents Guide

Bastille day parents guide Continue Viva la France! Bastille Day is here, and even if you're not in France, all you Francophiles can still party like is 1789. Le quatorze juillet, better known among English speakers as Bastille Day, is the time to come together to celebrate the assault of the Bastille, as well as the Fet de la Fedion, a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the Revolution, in 1790. Between the French military parade along the Champs-Elysees, an air show in the Parisian sky, fireworks showing that illuminate the Eiffel Tower, and many celebrations in cities around the world, there are many ways to celebrate La F't Nationale.If you have plans to throw your own soir'e in honor of the holiday, here's a roundup of Bastille Day ideas that will get you and your guests in the spirit of Galita Brotherhood. Go beyond wine and cheese pairs and greet guests with refreshing aperity and cocktails on the theme of the French Revolution. Serve up traditional French cuisine, as well as some spicy staples with a twist - like French onion cheese bread and cheddar croissant doughnuts - and discover everything you can do with pasta. Remodel your home in all the red, white and blue holiday decorations requires and impress with copious Parisian decor. Overcoming monarchical oppression is something we can all get behind, so come together to honor our shared history and throw a French holiday like no other.1 Send invitations full of French FlairCall to your friends to the repondes, s'il vous pla't on your rook with these screen printed greeting cards. -

Dušan Makavejev (1932-2019) Before the Successes of Emir Kusturica

Article Dusan Makavejev (1932-2019) Mazierska, Ewa Hanna Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/26119/ Mazierska, Ewa Hanna ORCID: 0000-0002-4385-8264 (2019) Dusan Makavejev (1932-2019). Studies in Eastern European Cinema . ISSN 2040- 350X It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2019.1583424 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Dušan Makavejev (1932-2019) Before the successes of Emir Kusturica, Dušan Makavejev was the best known director from Yugoslavia. Some of his enthusiasts regarded him as one of the leading figures of European film modernism, alongside such directors as Jean-Luc Godard and Miklós Jancsó. He was one of those innovators of the 1960s, who broke with the stale cinema dominating their countries in the previous decades. Others admired him for breaking social taboos, especially those regarding sexual behaviour. Finally, some saw him principally as a political filmmaker, engaged with Marxism, in a way which was typical for Yugoslav cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, but rare in other socialist countries, largely because the Yugoslav version of socialism was more democratic and open to criticism, as demonstrated by the work of Praxis philosophers from Belgrade and Zagreb.