Rosetta Stone: a Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers' Rosetta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Columbia Filmcolumbia Is Grateful to the Following Sponsors for Their Generous Support

O C T O B E R 1 8 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 9 20 TH ANNIVERSARY FILM COLUMBIA FILMCOLUMBIA IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT BENEFACTOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 20 TH PRODUCERS FILM COLUMBIA FESTIVAL SPONSORS MEDIA PARTNERS OCTOBER 18–27, 2019 | CHATHAM, NEW YORK Programs of the Crandell Theatre are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York filmcolumbia.org State Legislature. 5 VENUES AND SCHEDULE 9 CRANDELL THEATRE VENUES AND SCHEDULE 11 20th FILMCOLUMBIA CRANDELL THEATRE 48 Main Street, Chatham 13 THE FILMS á Friday, October 18 56 PERSONNEL 1:00pm ADAM (page 15) 56 DONORS 4:00pm THE ICE STORM (page 15) á Saturday, October 19 74 ORDER TICKETS 12:00 noon DRIVEWAYS (page 16) 2:30pm CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (page 17) á Sunday, October 20 11:00am QUEEN OF HEARTS: AUDREY FLACK (page 18) 1:00pm GIVE ME LIBERTY (page 18 3:30pm THE VAST OF NIGHT (page 19) 5:30pm ZOMBI CHILD (page 19) 7:30pm FRANKIE + DESIGN IN MIND: ON LOCATION WITH JAMES IVORY (short) (page 20) á Monday, October 21 11:30am THE TROUBLE WITH YOU (page 21) 1:30pm SYNONYMS (page 21) 4:00pm VARDA BY AGNÈS (page 22) 6:30pm SORRY WE MISSED YOU (page 22) 8:30pm PARASITE (page 23) á Tuesday, October 22 12:00 noon ICE ON FIRE (page 24) 2:00pm SOUTH MOUNTAIN (page 24) 4:00pm CUNNINGHAM (page 25) 6:00pm THE CHAMBERMAID (page 26) 8:15pm THE SONG OF NAMES (page 27) á Wednesday, October 23 11:30am SEW THE WINTER TO MY SKIN (page 28) 2:00pm MICKEY AND THE BEAR (page 28) 3:45pm CLEMENCY (page 29) 6:00pm -

C a H Ie R P É D a G O G Iq

Cahier pédagogique IFI Education l a e u g v a é m l o i n “nos sociétés starifient l’individu.” jEan -PiErrE dardEnnE cO -réalisatEur les Personnages 1. Avant le film Regardez l’affiche du film ci-contre et répondez aux questions ci-dessous. a) Après avoir vu Le gamin au vélo c) D’après vous l’affiche tente pensez-vous que l’affiche est une d’attirer quelle audience bonne représentation du film? pour ce film? b) Pourquoi ce cadre de la photo a-t-il été choisi? 2. Les Personnages Principaux s s u u n n e e l l P P e e n n i i t t s s i i r r h h C C © © Guy Wes Cyril Samantha a) Regardez les photos. Écrivez une description de chaque caractère. Ensuite comparez chaque personnage avec une autre du film. Utilisez les phrases et les adjectifs ci-dessous. Par exemple Cyril a l’air têtu. Il est mineur par contre Guy est adulte. Adjectifs hostile Des phrases utiles ensif compréh te malhonnê actif ux • Il / Elle a l’air… chaleure t têtu charman x • Je dirais qu’elle/il est _______ car _______ paresseu t distant accueillan • Il me semble qu’il / elle est impoli nête • Il est _______ par contre elle est _______ hon • Au début il est _______ mais à la fin il est _______ 3. Résumé 4. Expression écrite Trouvez la bonne terminaison de chaque phrase pour complétez le résumé ci-dessous. Écrivez les phrases complètes dans votre cahier. -

Festival Review 72Nd Festival De Cannes Finding Faith in Film

Joel Mayward Festival Review 72nd Festival de Cannes Finding Faith in Film While standing in the lengthy queues at the 2019 Festival de Cannes, I would strike up conversations with fellow film critics from around the world to discuss the films we had experienced. During the dialogue, I would express my interests and background: I am both a film critic and a theologian, and thus intrigued by the rich connections between theology and cinema. To which my interlocutor would inevitably raise an eyebrow and reply, “How are those two subjects even related?” Yet every film I saw at Cannes somehow addressed the question of God, religion or spirituality. Indeed, I was struck by how the most famous and most glamorous film festival in the Western world was a God-haunted environ- ment where religion was present both on- and off-screen. As I viewed films in competition for the Palme d’Or, as well as from the Un Certain Regard, Direc- tors’ Fortnight and Critics’ Week selections, I offer brief reviews and reflections on the religious dimension of Cannes 2019.1 SUBTLE AND SUPERFLUOUS SPIRITUALITY Sometimes the presence of religion was subtle or superfluous. For example, in the perfectly bonkers Palme d’Or winner, Gisaengchung (Parasite, Bong Joon- Ho, KR 2019), characters joke about delivering pizzas to a megachurch in Seoul. Or there’s Bill Murray’s world-weary police officer crossing himself and exclaim- ing (praying?), “Holy fuck, God help us” as zombie hordes bear down on him and Adam Driver in The Dead Don’t Die (Jim Jarmusch, US 2019). -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

A Film by Arantxa Echevarría

A film by Arantxa Echevarría CARMEN Y LOLA A love story between two gypsy girls ARANTXA ECHEVARRÍA FIRT SPANISH WOMAN DIRECTOR SELECTED FOR DIRECTORS FORTNIGHT CANNES FILM FESTIVAL SYNOPSIS Carmen is a gypsy teenager living in the outskirts of Madrid. Like every other gypsy woman, she is destined to live a life that is repeated generation after genera- tion: getting married and raising as many children as possible. But one day she meets Lola, an uncommon gypsy who dreams about going to university, draws bird graffiti and is very different. Carmen quickly deve- lops a complicity with Lola and discovers a world that, inevitably, leads them to be rejected by their families. CAST From the outset we knew we had to be faithful to the truth. There are very few actors and actresses in the gypsy world, since they rarely dare to follow that path. This was our big bet; finding two adolescents within the community who would dare to play these characters, despite the alienation that they may suffer because of the film. We searched in street markets, in suburbs, associations, even on the street. Throughout a challenging casting process which extended over 6 months, we saw over 1,000 gypsies, until we finally found our Lola and our Carmen. Only one character in the film is played by a pro- fessional actor, the rest are 150 gypsies with no prior experience in front of a camera. ZAIRA ROMERO – LOLA ROSY RODRÍGUEZ – CARMEN Zaira is a 16-year old “merchera”, a mix between gypsy Rosy was number 897, she appeared in the casting and white. -

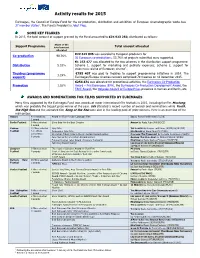

Activity Results for 2015

Activity results for 2015 Eurimages, the Council of Europe Fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematographic works has 37 member states1. The Fund’s President is Jobst Plog. SOME KEY FIGURES In 2015, the total amount of support granted by the Fund amounted to €24 923 250, distributed as follows: Share of the Support Programme total amount Total amount allocated allocated €22 619 895 was awarded to European producers for Co-production 90.76% 92 European co-productions. 55.76% of projects submitted were supported. €1 253 477 was allocated to the two schemes in the distribution support programme: Distribution 5.03% Scheme 1, support for marketing and publicity expenses; Scheme 2, support for awareness raising of European cinema2. Theatres (programme €795 407 was paid to theatres to support programming initiatives in 2014. The 3.19% support) Eurimages/Europa Cinemas network comprised 70 theatres on 31 December 2015. €254 471 was allocated for promotional activities, the Eurimages Co-Production Promotion 1.02% Award – Prix Eurimages (EFA), the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award, the FACE Award, the Odyssée-Council of Europe Prize, presence in Cannes and Berlin, etc. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR FILMS SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES Many films supported by the Eurimages Fund won awards at major international film festivals in 2015, including the film Mustang, which was probably the biggest prize-winner of the year. Ida attracted a record number of awards and nominations while Youth, the High Sun and the animated film Song of the Sea were also in the leading pack of prize-winners. -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

FIFF-PROGRAMME-2017-WEB 2.Pdf

#programme #films #events #emotions www.fiff.ch #fiff17 Souvenirs Achetez des souvenirs du FIFF Un bout de FIFF à la maison : à partir du 16.03.17, des produits dérivés du FIFF sont disponibles aux points de vente du Festival. Vous serez aussi chic que le Festival ! Holen Sie sich die FIFF 2017 Merchandise-Artikel Ein Stück FIFF für Zuhause: Ab dem 16.03.17 sind diverse FIFF- Artikel an den Verkaufsstellen des Festivals erhältlich. Sie werden festival-chic aussehen! Get Your FIFF 2017 Merchandise now! A piece of FIFF at home: As from 16.03.17, FIFF merchandise is available for purchase at the Festival’s points of sale. You’ll look festival-chic! 1 Souvenirs Festival International de Films de Fribourg Internationales Filmfestival Freiburg Fribourg International Film Festival Sommaire | Inhaltsverzeichnis | Contents #introduction #parallel #sections Souvenirs 1 Cinéma de genre Genrekino | Genre Cinema 65 Index des films Histoires de fantômes Filmverzeichnis Gespenstergeschichten Index of Films 6 Ghost stories Index des réalisateurs/trices Décryptage Verzeichnis der RegisseurInnen Entschlüsselt | Decryption 89 Index of Directors 8 Cabinet de curiosités cinématographiques Messages 12 Ein filmisches Kuriositätenkabinett A cinematic cabinet of curiosities Comité d’honneur Unterstützungskomitee Diaspora 109 Board of Honour 24 Myret Zaki et l’Egypte Myret Zaki und Ägypten Membres des jurys Myret Zaki and Egypt Jurymitglieder Jury members 27 Hommage à… 119 Freddy Buache Nouveau territoire #official #selection Neues Territorium | New Territory -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Painterly Style in Robert Bresson's Au Hasard Balthazar

Interin E-ISSN: 1980-5276 [email protected] Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná Brasil Watkins, Raymond Portrait of a Donkey: Painterly Style in Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar Interin, vol. 2, núm. 2, 2006, pp. 1-23 Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná Curitiba, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=504450755004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Portrait of a Donkey: Painterly Style in Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar Raymond Watkins “[Robert Bresson] . would have us be concerned here not with the psychology but with the physiology of existence” (133). —André Bazin, “ Le Journal d’un curé de campagne and the Stylistics of Robert Bresson” (1951) “Bresson’s cinema is closer to painting than to photography.” —François Truffaut Although commentary on Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar (1966) has focused on the film’s narrative structure,1 critics invariably point to its painterly qualities. During a roundtable discussion just after the film was released, Mireille Latil-Le Dantec observes that the film “more closely resembles a non-figurative painting than Bresson’s previous works.”2 In that same discussion Michel Estève speculates that because “painting was Bresson’s first passion and has greatly influenced him,” he “wanted to make a portrait” in the form of Balthazar.3 Summarizing his interview with Bresson while the film was still being shot at Guyancourt, Paul Gilles arrives at a similar conclusion: “Bresson is not a filmmaker, he’s a painter.”4 And according to Gilbert Salachas it is not Balthazar, but the characters around him who function as a collective portrait or painting.5 Even Bresson himself, reflecting on the decision to use a donkey as his protagonist, confirms much of the critical conjecture: “Perhaps the idea came to me plastically because I am a painter. -

300 Greatest Films 4 Black Copy

The goal in this compilation was to determine film history's definitive creme de la creme. The titles considered to be the greatest of the great from around the world and throughout the history of film. So, after an in-depth analysis of respected critics and publications from around the globe, cross-referenced and tweaked to arrive at the ranking of films representing, we believe, the greatest cinema can offer. Browse, contemplate, and enjoy. Check off all the films you have seen 1 Citizen Kane 1941 USA 26 The 400 Blows 1959 France 51 Au Hasard Balthazar 1966 France 76 L.A. Confidential 1997 USA 2 Vertigo 1958 USA 27 Satantango 1994 Hungary 52 Andrei Rublev 1966 USSR 77 Modern Times 1936 USA 3 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 UK 28 Raging Bull 1980 USA 53 All About Eve 1950 USA 78 Mr Hulot's Holiday 1952 France 4 The Rules of the Game 1939 France 29 L'Atalante 1934 France 54 Sunset Boulevard 1950 USA 79 Wings of Desire 1978 France 5 Seven Samurai 1954 Japan 30 Annie Hall 1977 USA 55 The Turin Horse 2011 Hungary 80 Ikiru 1952 Japan 6 The Godfather 1972 USA 31 Persona 1966 Sweden 56 Jules and Jim 1962 France 81 The Apartment 1960 USA 7 Apocalypse Now 1979 USA 32 Man With a Movie Camera 1929 USSR 57 Double Indemnity 1944 USA 82 Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie 1972 France 8 Tokyo Story 1953 Japan 33 E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 1982 USA 58 Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963 France 83 The Seventh Seal 1957 Sweden 9 Taxi Driver 1976 USA 34 Star Wars Episode IV 1977 USA 59 Belle De Jour 1967 France 84 Wild Strawberries 1957 Sweden 10 Casablanca 1942 USA 35