Dietary Profile of Rhinopithecus Bieti and Its Socioecological Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Dietary Profile of Rhinopithecus Bieti and Its Socioecological Implications'

Grueter, C C; Li, D; Ren, B; Wei, F; van Schaik, C P (2009). Dietary profile of Rhinopithecus bieti and its socioecological implications. International Journal of Primatology, 30(4):601-624. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: International Journal of Primatology 2009, 30(4):601-624. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 Dietary profile of Rhinopithecus bieti and its socioecological implications Grueter, C C; Li, D; Ren, B; Wei, F; van Schaik, C P Grueter, C C; Li, D; Ren, B; Wei, F; van Schaik, C P (2009). Dietary profile of Rhinopithecus bieti and its socioecological implications. International Journal of Primatology, 30(4):601-624. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: International Journal of Primatology 2009, 30(4):601-624. Dietary profile of Rhinopithecus bieti and its socioecological implications Abstract To enhance our understanding of dietary adaptations and socioecological correlates in colobines, we conducted a 20-mo study of a wild group of Rhinopithecus bieti (Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys) in the montane Samage Forest. This forest supports a patchwork of evergreen broadleaved, evergreen coniferous, and mixed deciduous broadleaved/ coniferous forest assemblages with a total of 80 tree species in 23 families. The most common plant families by basal area are the predominantly evergreen Pinaceae and Fagaceae, comprising 69% of the total tree biomass. -

Plant Introduction, Distribution, and Survival: a Case Study of the 1980 Sino-American Botanical Expedition

03 June Forum Dossman 5/13/03 2:58 PM Page 2 Forum Plant Introduction, Distribution, and Survival: A Case Study of the 1980 Sino-American Botanical Expedition MICHAEL DOSMANN AND PETER DEL TREDICI The 1980 Sino-American Botanical Expedition (SABE) to the Shennongjia Forest District, Hubei Province, China, was the first botanical collect- ing trip by American scientists to that country since 1949. It was significant because the area visited had high species diversity and because the col- lected germplasm was widely distributed to a variety of botanical institutions throughout North America and Europe. This report documents the survival of this germplasm after 22 years of cultivation. Of the original 621 SABE collections, 258 are represented by plants growing in at least 18 different botanical institutions. The fact that 115 of these collections (45 percent) are represented by a single accession growing in a single location suggests that the plant introduction process is much more tenuous than has been generally assumed. This study also highlights the importance of data sharing among botanical institutions as the most effective way of determining the uniqueness of a given collection and assessing its environ- mental adaptability or invasiveness, or both, over a broad range. Keywords: plant exploration; Shennongjia Forest District, China; collections’ documentation; invasive species nder the joint auspices of the Chinese Academy (2936 m), Xiaoshennongjia (3005 m), Dashennongjia (3052 Uof Sciences and the Botanical Society of America, the m), and Wuming Shan (3105 m) are the highest peaks in the 1980 Sino-American Botanical Expedition (SABE) investigated district (Bartholomew et al. 1983a). -

De Sorbus-Collectie in De Botanische Tuinen En Het Belmonte Arboretum Van De Landbouwhogeschool Te Wageningen

DRS. K. J. W. HENSEN DE SORBUS-COLLECTIE IN DE BOTANISCHE TUINEN EN HET BELMONTE ARBORETUM VAN DE LANDBOUWHOGESCHOOL TE WAGENINGEN IV (The Sorbits collection in the Botanical Gardens and Belmonte Arboretum of the Agricultural University at Wageningen. IV) In het 20ste Jaarboek van de Nederlandse Dendrologische Vereniging is een overzicht gegeven van de te Wageningen gekweekte Sorbus-pianten (HENSEN, 1957). Aanvullingen en wijzigingen verschenen in volgende jaarboeken (HENSEN, 1959 en 1963). Sedert de tekst van het laatste artikel geschreven werd, heeft opnieuw een aantal planten voor het eerst gebloeid en vrucht gedragen, zodat determinatie mogelijk werd. Van enige andere, reeds eerder in deze publikaties opgenomen planten werd de determinatie herzien. Deze aanvul lingen en wijzigingen van de vorige publikaties worden in dit artikel gepubliceerd. Aan gezien niet alle lezers van "Dendroflora" ook de Jaarboeken van de Nederlandse Dendrolo gische Vereniging ter beschikking zullen hebben, wordt aan het einde van dit artikel een lijst gegeven van alle taxa r), waarvan gedetermineerde planten in de Wageningense col lectie aanwezig zijn. De namen van soorten, variëteiten, apomicten of in het wild voorkomende hybriden worden gevolgd door de auteursnaam en een verwijzing naar de eerste publikatie van de naam. Deze wijziging bestaat uit de afgekorte titel, ev. het nummer van een boekdeel of jaargang van een tijdschrift, daarna de bladzijde en tenslotte het jaar van verschijnen. Namen van cultivars worden daarentegen gevolgd door de naam van de winner. Is deze niet bekend, dan laten wij de naam van de auteur volgen met een verwijzing naar de eerste publikatie van de naam. Synoniemen (cursief gedrukt) zijn slechts opgenomen, voor zover deze in botanische tuinen of in Nederlandse kwekerijen in gebruik zijn. -

Traditional Knowledge and Its Transmission of Wild Edibles Used

Geng et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:10 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0082-2 RESEARCH Open Access Traditional knowledge and its transmission of wild edibles used by the Naxi in Baidi Village, northwest Yunnan province Yanfei Geng1,2, Yu Zhang1, Sailesh Ranjitkar1,3, Huyin Huai4 and Yuhua Wang1* Abstract Background: The collection and consumption of wild edibles is an important part in livelihood strategies throughout the world. There is an urgent need to document and safeguard the wild food knowledge, especially in remote areas. The aims of this study are to accomplish detailed investigation of wild edibles used by the Naxi in Baidi village and evaluate them to identify innovative organic food products. Also, we aim to explore the characteristics of distribution and transmission of the traditional knowledge (TK) on wild edibles among the Naxi. Methods: Data was collected through a semi-structured interview of key informants above the age of 20 years, chosen carefully by a snowball sampling. The interviews were supplemented by free lists and participatory observation methods. Informants below 20 years were interviewed to test their knowledge of traditional practices. A quantitative index like Cultural Importance Index (CI) was used to evaluate the relative importance of the different wild edibles. Linear regression and t-test were performed to test variation in the TK among the informants of different age groups and genders. Results: Altogether 173 wild edible plant species belonging to 76 families and 139 genera were recorded in the study. Cardamine macrophylla, C. tangutorum and Eutrema yunnanense, have traditionally been consumed as an important supplement to the diet, particularly during food shortages as wild vegetables. -

Tree Planting and Management

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION Tree Planting and Management Breadth of Opportunity The spread of the Commission's responsibilities over some 148 countries in temperate, mediterranean, tropical and desert climates provides wonderful opportunities to experiment with nature's wealth of tree species. We are particularly fortunate in being able to grow many interesting and beautiful trees and we will explain how we manage them and what splendid specimens they can make. Why Plant Trees? Trees are planted for a variety of reasons: their amenity value, leaf shape and size, flowers, fruit, habit, form, bark, landscape value, shelter or screening, backcloth planting, shade, noise and pollution reduction, soil stabilisation and to encourage wild life. Often we plant trees solely for their amenity value. That is, the beauty of the tree itself. This can be from the leaves such as those in Robinia pseudoacacia 'Frisia', the flowers in the tropical tree Tabebuia or Albizia, the crimson stems of the sealing wax palm (Cyrtostachys renda), or the fruit as in Magnolia grandiflora. above: Sealing wax palms at Taiping War Cemetery, Malaysia with insert of the fruit of Magnolia grandiflora Selection Generally speaking the form of the left: The tropical tree Tabebuia tree is very often a major contributing factor and this, together with a sound knowledge of below: Flowers of the tropical the situation in which the tree is to tree Albizia julibrissin be grown, guides the decision to the best choice of species. Exposure is a major limitation to the free choice of species in northern Europe especially and trees such as Sorbus, Betula, Tilia, Fraxinus, Crataegus and fastigiate yews play an important role in any landscape design where the elements are seriously against a wider selection. -

18. SORBUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 477. 1753.1 花楸属 Hua Qiu Shu Lu Lingdi (陆玲娣 Lu Ling-Ti); Stephen A

Flora of China 9: 144–170. 2003. 18. SORBUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 477. 1753.1 花楸属 hua qiu shu Lu Lingdi (陆玲娣 Lu Ling-ti); Stephen A. Spongberg Aria (Persoon) Host; Micromeles Decaisne; Pleiosorbus Lihua Zhou & C. Y. Wu; Sorbus subgen. Aria Persoon. Trees or shrubs, usually deciduous. Winter buds usually rather large, ovoid, conical, or spindle-shaped, sometimes viscid; scales imbricate, several, glabrous or pubescent. Leaves alternate, membranous or herbaceous; stipules caducous, simple or pinnately com- pound, plicate or rarely convolute in bud; leaf blade usually serrate, sometimes nearly entire, venation craspedodromous or campto- dromous, glabrous or pubescent. Inflorescences compound, rarely simple corymbs or panicles. Hypanthium campanulate, rarely ob- conical or urceolate. Sepals 5, ovate or triangular, glabrous, pubescent, or tomentose, sometimes glandular along margin. Petals 5, glabrous or pubescent, base clawed or not. Stamens 15–25(–44) in 2 or 3 whorls, unequal in length; anthers ovoid or subglobose. Carpels 2–5, partly or wholly adnate to hypanthium; ovary semi-inferior to inferior, 2–5(–7)-loculed, with 2 or 3(or 4) ovules per locule, one usually abortive; styles 2–5, free or partially connate, glabrous or pubescent. Fruit a pome, white, yellow, pink, or brown to orange or red, ovoid or globose to ellipsoid or oblong, usually small, glabrous or pubescent, laevigate or with small lenticels, apically with sepals persistent or caducous leaving an annular scar, with 2–5(–7) locules, each with 1 or 2 exendospermous seeds; seeds several, with thin perisperm and endosperm enclosing embryo with compressed cotyledons. About 100 species: widely distributed throughout temperate regions of Asia, Europe, and North America; 67 species (43 endemic) in China. -

The Genome Sequence of Sorbus Pohuashanensis Provides Insights Into Population Evolution And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.27.457897; this version posted August 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The genome sequence of Sorbus pohuashanensis provides insights into population evolution and 2 leaf sunburn response 3 4 Running title: Genome sequence and leaf sunburn of S. pohuashanensis 5 6 Dongxue Zhao 1#, Yan Zhang1#, Yizeng Lu 2#, Liqiang Fan 3, Zhibin Zhang 3, Mao Chai3*, Jian Zheng 7 1* 8 9 1. School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing University of Agriculture, Beijing, 102206, China 10 2. Shandong Provincial Center of Forest Tree Germplasm Resources, Jinan, Shandong Province, 250102, 11 China 12 3. Institute of Cotton Research of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Anyang, Henan 13 province, 455000, China 14 15 Authors’ official email: 16 Dongxue Zhao: [email protected] 17 Yan Zhang: [email protected] 18 Yizeng Lu: [email protected] 19 Jian Zheng: [email protected] 20 Mao Chai: [email protected] 21 Liqiang Fan: [email protected] 22 Zhibin Zhang: [email protected] 23 24 # These authors contributed equally to this work. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.27.457897; this version posted August 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

The Genome Sequence of Sorbus Pohuashanensis Provides Insights Into Population Evolution and Leaf Sunburn Response

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.27.457897; this version posted August 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The genome sequence of Sorbus pohuashanensis provides insights into population evolution and 2 leaf sunburn response 3 4 Running title: Genome sequence and leaf sunburn of S. pohuashanensis 5 6 Dongxue Zhao 1#, Yan Zhang1#, Yizeng Lu 2#, Liqiang Fan 3, Zhibin Zhang 3, Mao Chai3*, Jian Zheng 7 1* 8 9 1. School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing University of Agriculture, Beijing, 102206, China 10 2. Shandong Provincial Center of Forest Tree Germplasm Resources, Jinan, Shandong Province, 250102, 11 China 12 3. Institute of Cotton Research of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Anyang, Henan 13 province, 455000, China 14 15 Authors’ official email: 16 Dongxue Zhao: [email protected] 17 Yan Zhang: [email protected] 18 Yizeng Lu: [email protected] 19 Jian Zheng: [email protected] 20 Mao Chai: [email protected] 21 Liqiang Fan: [email protected] 22 Zhibin Zhang: [email protected] 23 24 # These authors contributed equally to this work. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.27.457897; this version posted August 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Otiorhynchus Armadillo (Rossi, 1792) (Coleoptera, Curculioidae), a Weevil New to Norway

© Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 17 June 2010 Otiorhynchus armadillo (Rossi, 1792) (Coleoptera, Curculioidae), a weevil new to Norway ARNSTEIN STAVERLØKK Staverløkk, A. 2010. Otiorhynchus armadillo (Rossi, 1792) (Coleoptera, Curculioidae), a weevil new to Norway. Norw. J. Entomol. 57, 9–11. The first record of the weevil Otiorhynchus armadillo (Rossi, 1792) (Coleoptera, Curculioidae) from Norway is given. The biology and geographical distribution is commented on. Key words: Otiorhynchus armadillo, alien species, Coleoptera, Curculioidae, Norway. Arnstein Staverløkk, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Department of Terrestrial Ecology, NO-7485 Trondheim, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction was recorded again at the same location, indicating that the species had managed to overwinter and Many Otiorhynchus species can cause serious establish. damage to a lot of plants and reach large numbers in quite a short time, e.g. O.sulcatus (Fabricius, Discussion 1775) in strawberry fields and horticultural plants. The adults often feed on the foliage of different O. armadillo is known from 10 countries in host plants making round cuts along the leaf edge Europe (Alonso-Zarazaga 2007), but it is probably (Figure 1), while the larvae feed on the roots. more widespread due to trade of plants. From Otiorhynchus species are an economical threat Sweden, it was recorded from a plant nursery to farmers and producers of plants who use lots in Stockholm in 1995 (Borisch 1997). The first of resources every year preventing the damage specimen from Great Britain was recorded in of weevils. Several pest species are expanding 1998 near a store that sold imported plants in their prevalence and reports from the Netherlands London. -

Page 1 the Following Pages Outline Phasing Recommendations for The

Kruckeberg Botanic Garden Master Site Plan PHASING AND IMPLEMENTATION he following pages outline phasing recommendations for the KruckebergT Botanic Garden that seem desirable to address the needs, vision, and requirements of a private garden’s evolution into the publc domain. With the transfer of this property from a private residence to a commercial public entity, new sets of codes, restrictions, and opportunities come into play. These deal with public safety, health, and well-being and ensure that equal opportunities are afforded to all. Within a limited budget, Phase 1 responds to these immediate needs by providing on-site public parking to reduce impacts to the surrounding residential community, adding much needed public restrooms, and creating a permanent and separate service access road and staff parking area. Phase 2 focuses on siting an interpretive switchback boardwalk trail that connects the upper and lower gardens in an aesthetic ADA-compliant manner. It is also envi- sioned that an ADA-compliant loop path would be routed through the lower garden. While it would be optimal to build the environmental learning center in Phase 2, it is recognized that lack of funding may require deferment to a later phase. Further development of future phases depends on many factors, most importantly securing funding and the commitment of the City, Foundation, and public to sup- port and encourage new work to proceed. In the end, this alone will determine how quickly Garden projects are completed and the Garden vision, as outlined in this report, is realized. This is a modest plan as represented by the development costs associated with each phase in 2010 dollars. -

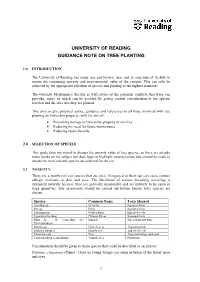

University of Reading Guidance Note on Tree Planting

UNIVERSITY OF READING GUIDANCE NOTE ON TREE PLANTING 1.0 INTRODUCTION The University of Reading has many rare and historic trees and is conscious of its duty to ensure the continuing amenity and environmental value of the campus. This can only be achieved by the appropriate selection of species and planting to the highest standards. The Grounds Maintenance Section is well aware of the potential conflicts that trees can provoke, many of which can be avoided by giving careful consideration to the species selected and the sites that they are planted. This aims to give practical advice, guidance and references to all those involved with tree planting on University property, with the aim of: • Preventing damage to University property or services • Reducing the need for future maintenance • Reducing future hazards 2.0 SELECTION OF SPECIES This guide does not intend to discuss the amenity value of tree species, as there are already many books on the subject but does hope to highlight considerations that should be made to ensure the most suitable species are selected for the site. 2.1 TOXICITY There are a number of tree species that are toxic if ingested or their sap can cause contact allergic reactions to skin and eyes. The likelihood of serious poisoning occurring is extremely unlikely because trees are generally unpalatable and are unlikely to be eaten in large quantities. Site assessment should be carried out before known toxic species are chosen. Species Common Name Toxic Hazard Aesculus sp. Chestnut Ingested fruits Ilex sp. Holly Ingested fruits Laburnum sp. Golden Rain Ingested seeds Ligustrum lucidum Chinese Privet Ingested fruits Rhus sp. -

WO 2016/016826 Al 4 February 2016 (04.02.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/016826 Al 4 February 2016 (04.02.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: xyAJ PARK; Level 22, State Insurance Tower, 1 A01H 1/06 (2006.01) C12N 15/61 (2006.01) Willis Street, Wellington (NZ). C12N 15/29 (2006.01) A01H 5/08 (2006.01) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C12N 15/113 (2010.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (21) International Application Number: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, PCT/IB2015/055743 BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 30 July 2015 (30.07.2015) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, (25) Filing Language: English MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, (30) Priority Data: TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. 6282 14 1 August 2014 (01.08.2014) NZ (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (72) Inventors; and kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicants : DARE, Andrew Patrick [NZ/NZ]; 40 Jef GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, ferson Street, Glendowie, Auckland, 1071 (NZ).