Iain Crichton Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iain Crichton Smith 1928 - 1998

Iain Crichton Smith 1928 - 1998 Contents: Biography.................................................................................................................................................................Page 1 Two Old Women .....................................................................................................................................Pages 2 - 6 The End of An Auld Sang ....................................................................................................................Pages 6 - 8 The Beginning of a New Song....................................................................................................................Page 8 Further Reading / Contacts.............................................................................................................Pages 9 - 12 Biography: Iain Crichton Smith (1928 - 1998) (his gaelic name was Iain Mac a ‘Ghobhainn’) was born in Glasgow in 1928, Smith grew up from the age of two on the island of Lewis. The language of his upbringing was Gaelic; he learned English as his second language when he went to school at the Nicolson Institute in Stornoway. Later, he took a degree in English at the University of Aberdeen. From there he became a school teacher in Clydebank then Oban, where he could con- template his island upbringing at close range, but with a necessary degree of detachment. He retired early from teaching in 1977 to concentrate on his writing. Smith won various literary awards and was made an OBE in 1980. He published work in Gaelic under the -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Iain Crichton Smith Essays

fi(tut j ttud\ by ll^i Strulh PhQlttgTjpttH lain Crichton Smith is one of the most celebrated and challenging writers in contemporary British literature. A poet, novelist and dramatist in both English and Gaelic, he is also a distinguished critic whose essays have a wide circle of admirers. Now published together for the first time, his essays enable us to see the range of his interests and concerns. As a Gaelic speaker Smith is intensely aware of the recession in his native language and of the threat to that culture's well-being. Nowhere is that concern more coherently expressed than in his previously unpublished autobiographical essay 'Real People in a Real Place* which opens this collection. The poetry of his fellow Scots poet Hugh MacDiarmid is another abiding interest, one which he explores with great felicity and feeling. Other poets whose work interests him arid about whom he has written with grace and intelligence are George Bruce and Robert Garioch. Above all it is poetry and the matter of poetry that commands his interest and it is that intellectual concern which dominates this fascinating collection. ISBN 0 86334 059 8 £7.95 LINES REVIEW EDITIONS ~f~b <^/fcpf "T iff fc </m /9-<S © Iain Crichton Smith 1986 Contents ISBN 0 86334 059 8 Introductory Note by Derick Thomson 7 Published in 1986 by PART ONE Macdonald Publishers Real People in a Real Place 13 Loanhead, Midlothian EH20 9SY PART TWO: THE POET'S WORLD Between Sea and Moor 73 A Poet in Scotland 84 The publisher acknowledges the financial Poetic Energy, Language and Nationhood 87 assistance of the Scottish Arts Council in the publication of this volume PART THREE: THE GAELIC POET Modern Gaelic Poetry 97 George Campbell Hay: Language at Large 108 The Modest Doctor: The Poetry of Donald MacAulay 116 This PDF file comprises lain Crichton Smith's two essays, "Real People in a Real World" Gaelic Master: Sorley MacLean 123 and "Between Sea and Moor". -

Issue 7 Biography Dundee Inveramsay

The Best of 25 Years of the Scottish Review Issue 7 Biography Dundee Inveramsay Edited by Islay McLeod ICS Books To Kenneth Roy, founder of the Scottish Review, mentor and friend, and to all the other contributors who are no longer with us. First published by ICS Books 216 Liberator House Prestwick Airport Prestwick KA9 2PT © Institute of Contemporary Scotland 2021 Cover design: James Hutcheson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-8382831-6-2 Contents Biography 1 The greatest man in the world? William Morris Christopher Small (1996) 2 Kierkegaard at the ceilidh Iain Crichton Smith Derick Thomson (1998) 9 The long search for reality Tom Fleming Ian Mackenzie (1999) 14 Whisky and boiled eggs W S Graham Stewart Conn (1999) 19 Back to Blawearie James Leslie Mitchell (Lewis Grassic Gibbon) Jack Webster (2000) 23 Rescuing John Buchan R D Kernohan (2000) 30 Exercise of faith Eric Liddell Sally Magnusson (2002) 36 Rose like a lion Mick McGahey John McAllion (2002) 45 There was a man Tom Wright Sean Damer (2002) 50 Spellbinder Jessie Kesson Isobel Murray (2002) 54 A true polymath Robins Millar Barbara Millar (2008) 61 The man who lit Glasgow Henry Alexander Mavor Barbara Millar (2008) 70 Travelling woman Lizzie Higgins Barbara Millar (2008) 73 Rebel with a cause Mary -

Gaelic Scotland and Gaelic Ireland in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications MacGregor, Martin (2000) Làn-mara 's mìle seòl ("Floodtide and a thousand sails"): Gaelic Scotland and Gaelic Ireland in the Later Middle Ages. In: A' Chòmhdhail Cheilteach Eadarnìseanta Congress 99: Cultural Contacts Within the Celtic Community: Glaschu, 26-31 July. Celtic Congress, Inverness, pp. 77-97. Copyright © 2000 The Author http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91505/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk ‘Làn-mara ’s mìle seòl’ (Floodtide and a Thousand Sails): Gaelic Scotland and Gaelic Ireland in the Later Middle Ages Martin MacGregor I Bha thu aig Gaidheil Eirinn Mar fhear dhiubh fhéin ’s de’n dream. Dh’ aithnich iad annad-sa an fhéile Nach do reub an cuan, Nach do mhill mìle bliadhna: Buaidh a’ Ghàidheil buan. [You were to the Gaels of Ireland as one of themselves and their people. They knew in you the humanity that the sea did not tear, that a thousand years did not spoil: the quality of the Gael permanent.]1 The words of Sorley MacLean have become something of a Q-Celtic clarion call in recent years. They commemorate his brother Calum, whose work on each side of the North Channel on behalf of the Irish Folklore Commission and of the School of Scottish Studies, recording the oral tradition of those whom Calum, quoting the Irish poet F. R. Higgins, described as ‘the lowly, the humble, the passionate and knowledgeable stock of the Gael’,2 is as potent a symbol as there could be of the continuing reality of a greater Gaeldom, however attenuated, into our own times. -

Expressions of Existentialism and Absurdity in Gaelic Drama

The closed room: expressions of existentialism and absurdity in Gaelic drama Michelle Macleod, University of Aberdeen Introduction This paper is an exploration of six Gaelic plays written in the 1960s and 1970s: in particular it seeks to contextualise them with European drama of a roughly contemporaneous period by the likes of Ionesco, Sartre, Beckett and to demonstrate the internationalism of this genre of Gaelic writing. In the period under consideration Gaelic drama was most commonly performed as a one-act competition piece by amateur companies, (Macleod 2011) and the plays considered here were all part of that genre. While the Scottish Community Drama Association and An Comunn Gaidhealach competitions might seem far removed from Parisian and London theatres, the influence of the latter over the content of some of the former is visible. The articles in this journal and Macleod (2011) show that Gaelic drama has made a major contribution to the development of cultural expression within the Gaelic community on account of the volume of plays produced in amateur companies across the country and the number of people engaging actively with the arts. This paper, though not an exhaustive study of the Gaelic drama of this era, is a demonstration of the importance and excellence of this genre. It teases out various themes from Absurdist and existential theatre in other languages and uses some of the extensive scholarship of that drama as a mechanism to consider a selection of plays by three playwrights Finlay MacLeod (Fionnlagh MacLeòid) (1937-), Donnie Maclean (Donaidh MacIlleathain) (1939-2003) and Iain Crichton Smith (Iain Mac a’ Ghobhainn) (1928-1998), all from the Isle of Lewis. -

Inventory Acc.12600 Iain Crichton Smith

Acc.12600 February 2007 Inventory Acc.12600 Iain Crichton Smith National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Papers, 1962-2000, of and relating to Iain Crichton Smith (1928-1998), poet and writer in Gaelic and English. Iain Crichton Smith was born in Lewis and educated at the Nicholson Institute (Stornoway) and the University of Aberdeen. He was a teacher by profession and taught at schools in Clydebank, Dumbarton and Oban until he retired in 1977 to pursue his writing career. Prolific, both in his native Gaelic and in English, he favoured exploring themes of island culture and religion. Though first and foremost a poet, he also produced novels, short stories, plays and criticism. Sadly for posterity, he did not keep many of his manuscripts; what is here probably amounts to the major archive of Iain Crichton Smith. Bought, 2006 1-2 Literary manuscripts and papers 3-8 Radio and play scripts 9-36 Correspondence 37 Diaries 38-46 Miscellaneous 47-63 Press cuttings 64 Printed material 65 Printed ephemera 1-2 Literary manuscripts and papers 1 Manuscripts and typescripts of (?unpublished) poems, and a manuscript notebook containing poems, a short untitled play and a biography of Sorley Maclean. 2 Prose, articles and other material. Includes ‘The Future of Gaelic Literature’ by Iain Crichton Smith as published in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, 1962; typescript of a Murdo story (?Murdo and Death); typescript of essay, ‘Towards the Human’; transcript of ‘Conversation with Iain Crichton Smith at the Poet’s home in Oban on 14th March 1981’; photocopies and notes relating to the life and work of Sorley Maclean; miscellaneous notes and pieces (including an essay comparing Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter with Hogg’s Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, possibly not written by Iain Crichton Smith, but with his ms amendments and corrections). -

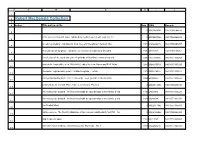

Robert Macdonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, Part No

A B C D E F 1 2 Robert MacDonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, part no. & title Date ISBN Barcode 0 M0019855HL 38011050264616 5 51 beauties of Scottish song : adapted for medium voices with tonic sol-fa / 0 M0006030HL 38011050265076 6 A Celtic miscellany : translations from the Celtic literatures / Kenneth Hur 1971 0140442472 38011050265357 7 A chuidheachd mo ghaoil : laoidean / air an seinn le Cairstiona Sheadha 1990 q8179317 38011050265662 8 A collection of the vocal airs of the Highlands of Scotland : communicated a 1996 1871931665 38011551310264 9 Acts of the Lords ofthe Isles 1336-1493 / edited by Jean Munro and R.W. Munr 1986 0906245079 38011551867255 10 Amannan : sgialachdan goimi / Pòl MacAonghais ... (et al.) 1979 055021402x 38011551310512 11 Am feachd Gaidhealach : ar tir 's ar teanga : lean gu dlùth ri cliù do shinn 1944 w3998157 38011551310850 12 A Mini-Guide to Cornish. Place Names, Dictionary, Phrases 0 M0023438HL 38011050270191 13 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551310421 14 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551311031 15 [An Dealbh Mhor] 0 M0023413HL 38011551315883 16 An Deo Greine. The Monthly Magazine of An Comunn Gaidhealach. Vol.XV1, No. 0 M0021209HL 38011050266405 17 And it came to pass 1962 b6219267 38011551865341 18 An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.1 1983 0950261238 38011551866331 19 A B C D E F An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.2 1987 0950261262 38011551866349 20 An Leabhar mo`r = The great book of Gaelic / edited by Malcolm Maclean and T 2002 1841952494 38011551311411 21 AN ROSARNACH:AN CEATHRAMH LEABHARBOOK 4. -

Carcanet New Books 2011

N EW B OOKS 2 0 1 1 Chinua Achebe John Ashbery Sujata Bhatt Eavan Boland Joseph Brodsky Paul Celan Inger Christensen Gillian Clarke Donald Davie Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) Over forty years of great poetry Iain Crichton Smith Elaine Feinstein Carcanet Celebrates 40 Years...from Carcanet... Louise Glück Jorie Graham W.S. Graham Robert Graves Ivor Gurney Marilyn Hacker Sophie Hannah John Heath-Stubbs Elizabeth Jennings Brigit Pegeen Kelly Mimi Khalvati Thomas Kinsella R. F. Langley Hugh MacDiarmid L ETTER FROM THE E DITOR As this catalogue goes to press, I’m editing New Poetries V, an introductory anthology of work by writers several of whom will publish Carcanet first collections in coming years. They come from the round earth’s imagined corners – from Singapore and Stirling, Cape Town and Cambridge, Dublin and Washington – and from England. They share a vocation for experimenting with form, tone and theme. From India, Europe and America a Collected Poems by Sujata Bhatt, and from South Africa and Yorkshire a new collection by Carola Luther, indicate the geographical scope of the Carcanet list. For eight years readers have waited to accompany Eavan Boland on her critical Journey with Two Maps: in April, at last we set out. We also encounter an anthology of British surrealism that changes our take on the tradition. Translation, classic and contemporary, remains at the heart of our reading. John Ashbery’s embodiment of Rimbaud’s Illuminations is his most ambitious translation project since his versions of Pierre Martory. Fawzi Karim from Iraq, Toon Tellegen from the Netherlands, the Gawain Poet from Middle English and Natalia Gorbanevskaya from Russia explore historical, allegorical and legendary landscapes and bring back trophies… And from America, a first European edition of the most recent US Poet Laureate, Kay Ryan. -

Conversations Scottish Poets

Conversations with Scottish Poets Marco Fazzini Conversations with Scottish Poets © Marco Fazzini, 2015 Aberdeen University Press University of Aberdeen Aberdeen AB24 3UG Typeset by the Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Anthony Rowe, Eastbourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-85752-029-3 The right of Marco Fazzini to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Contents Gifts as Interviews: A Preface v Norman MacCaig 1 Sorley Maclean 11 Edwin Morgan 17 Derick Thomson 37 Iain Crichton Smith 45 Alasdair Gray 53 Kenneth White 61 Douglas Dunn 77 Valerie Gillies 91 Christopher Whyte 101 John Burnside 111 David Kinloch 123 Robert Crawford 141 Don Paterson 151 Illustrations Norman MacCaig by Franco Dugo 3 Sorley Maclean by Franco Dugo 13 Edwin Morgan by Paolo Annibali 19 Derick Thomson by Franco Dugo 39 Iain Crichton Smith by Franco Dugo 47 Alasdair Gray by Franco Dugo 55 Kenneth White by Paolo Annibali 63 Douglas Dunn by Nicola Nannini 79 Valerie Gillies by Nicola Nannini 93 Christopher Whyte by Nicola Nannini 103 John Burnside by Doriano Scazzosi 113 David Kinloch by Nicola Nannini 125 Robert Crawford by Nicola Nannini 143 Don Paterson by Nicola Nannini 153 Gifts as Interviews: a Preface When I think about the genesis of this book, I can point to an exact time: it all began in Edinburgh in the summer of 1988. I first encountered Edwin Morgan’s poetry when I first met him. -

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS Piotr Stalmaszczyk “LANGUAGE IS

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTERARIA ANGLICA 7, 2007 Piotr Stalmaszczyk “LANGUAGE IS AT THE HEART OF MY WORK”: A NOTE ON THE POETRY OF IAIN CRICHTON SMITH (IAIN MAC A’GHOBHAINN) 1. INTRODUCTION One of the more interesting developments in twentieth-century Scottish Gaelic culture was the renaissance of poetry, especially in the second half of the century. Scottish Gaelic is spoken now by less than sixty thousand people, practically all of them English-speaking. However, in spite of this considerable decline in the number of Gaelic speakers, and to some extent also culture, the twentieth century saw a remarkable flowering of Gaelic literature, especially poetry.1 Traditional Gaelic poetry had an elaborate system of metres, it made use of end-rhyme, internal rhyme, alliteration, assonance, and introduced variation in line and stanza length. Early bardic verse in Ireland and Scotland observed a number of conventions and normative prescriptions, and bards were required to master specific linguistic knowledge necessary to construct appropriate verse. Modern Gaelic poetry differs from traditional in both form and content. Of the most important 20lh century Gaelic poets, George Campbell Hay (Deorsa Mac Iain Deorsa, 1915-1984) and Sorley MacLean (Somhairle MacGill-Eain, 1911-1996) worked within traditional metrical frameworks: George Campbell Hay revitalized traditional forms and created new elaborate sound-patterns, whereas Sorley MacLean crea tively transformed old patterns. Iain Crichton Smith (Iain Mac a’Ghobhainn, 1928-1998) often used regular length and rhyme but with variations of rhythm (a technique similar to the one used in his English poems). Derick ' Cf. the comments in the introductions to the collections of Gaelic poetry edited by MacAulay (1976), Davitt and MacDhomhnaill (1993), and Black (1999).