Iain Crichton Smith Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iain Crichton Smith 1928 - 1998

Iain Crichton Smith 1928 - 1998 Contents: Biography.................................................................................................................................................................Page 1 Two Old Women .....................................................................................................................................Pages 2 - 6 The End of An Auld Sang ....................................................................................................................Pages 6 - 8 The Beginning of a New Song....................................................................................................................Page 8 Further Reading / Contacts.............................................................................................................Pages 9 - 12 Biography: Iain Crichton Smith (1928 - 1998) (his gaelic name was Iain Mac a ‘Ghobhainn’) was born in Glasgow in 1928, Smith grew up from the age of two on the island of Lewis. The language of his upbringing was Gaelic; he learned English as his second language when he went to school at the Nicolson Institute in Stornoway. Later, he took a degree in English at the University of Aberdeen. From there he became a school teacher in Clydebank then Oban, where he could con- template his island upbringing at close range, but with a necessary degree of detachment. He retired early from teaching in 1977 to concentrate on his writing. Smith won various literary awards and was made an OBE in 1980. He published work in Gaelic under the -

Garioch Community Planning E-Bulletin 4 February 2021

Garioch Community Planning E-Bulletin 4 February 2021 If you have information which you think we should include in a future bulletin, please e-mail or forward it to [email protected] *PLEASE CHECK EACH SECTION FOR NEW AND UPDATED INFORMATION* (Photo credit: Aberdeenshire Council Image Library) Contents : (click on heading links below to skip to relevant section) Guidance Service Changes Community Resilience Support & Advice Health & Wellbeing Survey & Consultations Funding Guidance Links to national and local guidance *NEW* Latest Update from The Scottish Government From 2 February, mainland Scotland continues with temporary Lockdown measures in place, with guidance to stay at home except for essential purposes (this includes guidance on work within people’s homes - that this should only be taking place where essential) and working from home. In summary, today’s highlights are as below but please also see the video this article: • Nicola Sturgeon says although progress is being made on controlling the virus, restrictions will remain for "at least" the rest of the month • Pupils will begin a phased return to school from 22 February with the youngest going back to the classroom first • Senior pupils who have practical assignments to complete will be allowed to return on a "part-time" basis, with no more than 8% of the school roll attending "at any one time" • A "managed quarantine" requirement is to be introduced for anyone arriving directly into Scotland, regardless of which country they have come from You can view the most up to date information on the main Coronavirus page The latest Lockdown restrictions include further information has been added for guidance on moving home . -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

IFAJ World Congress: Scotland

IFAJ World Congress: SCOTLAND The International Federation of Agricultural Journalists World Congress showed the ‘Innovations From a Small Island’ to 212 journalists from 37 countries. Photo story by Kasey Brown, associate editor CONTINUED ON PAGE 238 236 n ANGUSJournal n November 2014 SCOTLAND CONTINUED FROM PAGE 236 1 2 4 3 5 1. Unlike in the United States, “A taste of Angus” means food and drink 7. Mackie’s produces its own honeycomb for its new chocolate line and from the city of Angus, instead of a juicy steak. its ice cream. Mackie’s uses 40,000 kg of honeycomb each year. To ensure quality, they manufacture it themselves. For items that Mackie’s 2. Journalists were given an overview of Scottish agriculture at the can not produce or manufacture themselves, they source as many beginning of the Congress. Emma Penny, editor of Farmers Guardian; Scottish products as possible. James Withers, CEO of Scotland Food and Drink; Daniel Cusick, Scottish Enterprise; and Nigel Miller, president of the National Farmers Union 8. Mackie’s new chocolate line adds the enterprise to the 70 Scottish Scotland; explain the challenges and opportunities for Scottish chocolatiers, an industry with an estimated value of £3.8 billion. agriculture. 9. Low-stress animal handling was a prevalent theme journalists 3 & 4. Thainstone Exchange is Europe’s largest farmer-owned livestock experienced on farms. This was posted prominently in the Mackie’s auction market. While the chants sounded different than U.S. auctions, milking parlor. animal ages and weights were still given. 10. Mackie’s dairy herd consists of Holstein Fresians crossed with 5. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

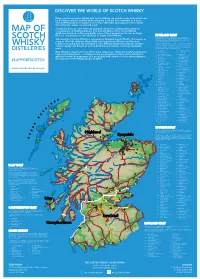

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Eadar Canaan Is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson's Lewis Poetry

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 46 Issue 1 Article 14 8-2020 Eadar Canaan is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson’s Lewis Poetry Petra Johana Poncarová Charles University, Prague Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, and the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons Recommended Citation Poncarová, Petra Johana (2020) "Eadar Canaan is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson’s Lewis Poetry," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 46: Iss. 1, 130–142. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol46/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EADAR CANAAN IS GARRABOST (BETWEEN CANAAN AND GARRABOST): RELIGION IN DERICK THOMSON’S LEWIS POETRY Petra Johana Poncarová Since the Scottish Reformation of the sixteenth-century, the Protestant, Calvinist forms of Christianity have affected Scottish life and have become, in some attitudes, one of the “marks of Scottishness,” a “means of interpreting cultural and social realities in Scotland.”1 However treacherous and limiting such an assertion of Calvinism as an essential component of Scottish national character may be, the experience with radical Presbyterian Christianity has undoubtedly been one of the important features of life in the -

Eadar Croit Is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an Fhicheadamh Linn | University of Glasgow

09/25/21 Eadar Croit is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an fhicheadamh linn | University of Glasgow Eadar Croit is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an View Online fhicheadamh linn @article{Mac A’ Ghobhainn_1983, place={Glaschu}, title={‘An Dotair Leòinte: Bàrdachd Dhòmhnaill MhicAmhlaigh (Ath-sgrùdadh)’}, volume={125}, journal={Gairm}, publisher={[s.n.]}, author={Mac A’ Ghobhainn, I.}, year={1983}, pages={68–73} } @book{Mac A’ Ghobhainn_2014, place={Inbhir Nis}, title={Bannaimh nach gann: a’ bhàrdachd aig An t-Urramach Murchadh Mac a' Ghobhainn, 1878-1936}, publisher={Clò Fuigheagan}, author={Mac A’ Ghobhainn, Murchadh}, editor={Smith, Maggie}, year={2014} } @book{Bennett_Rice_Bennett_Bennett_MacCallum_MacCallum_MacCallum_2014, place={Ochtertyre}, title={Eilean Uaine Thiriodh: beatha, òrain agus ceòl Ethel NicChaluim = The green isle of Tiree : the life, songs and music of Ethel MacCallum}, publisher={Grace Note Publications}, author={Bennett, Margaret and Rice, Eric and Bennett, Margaret and Bennett, Margaret and MacCallum, Ethel and MacCallum, Ethel and MacCallum, Ethel}, year={2014} } @book{Black_1999a, place={Edinburgh}, title={An tuil: anthology of 20th century Scottish Gaelic verse}, publisher={Polygon}, author={Black, Ronald}, year={1999} } @book{Black_1999b, place={Edinburgh}, title={An tuil: anthology of 20th century Scottish Gaelic verse}, publisher={Polygon}, author={Black, Ronald}, year={1999} } @book{Brown_Dawson Books_2007a, place={Edinburgh}, title={The Edinburgh history of Scottish literature: Volume 3: Modern transformations: new identities (from 1918)}, -

Celebrating Tour of Britain

Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council are delighted to welcome the final stage 8 of the 2021 Tour of Britain professional cycle race to the region for the first time on Sunday 12 September. This will mark the furthest north the race has ever visited. WINDOW DRESSING COMPETITION To celebrate the 2021 Tour of Britain, any business based in Aberdeenshire is encouraged to dress their window(s) with a cycling design or theme. You are encouraged to be as creative as you like. You may wish to view the official website https://www.tourofbritain.co.uk/ for ideas. How to enter Prizes You can enter your business into the Tour of Six equal prizes are on offer. Britain window dressing competition by emailing These prizes have been selected [email protected], no later than Friday to help winners promote their 3 September 2021. businesses in the region. We ask that window displays are completed by The best dressed window in each Monday 6 September and stay in place until Monday of the six administrative areas of 13 September, to allow judging to take place. Aberdeenshire: Banff & Buchan, Buchan, Formartine, Garioch, Marr Photographs of the display should be emailed and Kincardine & Mearns will each to [email protected] by 5pm receive a prize to the value of £1,000 on Monday 6 September. to spend on advertising of their The winners will be announced individual choice, in the North-east, on Monday 13 September. to promote their business. If you are promoting your window display on social media, please remember to use the hashtag #ToBABDN If you have any questions regarding any of the above, please don’t hesitate to get in touch by emailing [email protected] Please note, our colleagues in Aberdeen City Council are running a Window Dressing Competition and a Hidden Object Competition for licenced premises, hotels and commercial premises based in Aberdeen City. -

Memorials of Angus and Mearns, an Account, Historical, Antiquarian, and Traditionary

j m I tm &Cfi mm In^fl^fSm MEMORIALS OF ANGUS AND THE MEARNS AN ACCOUNT HISTORICAL, ANTIQUARIAN, AND TRADITIONARY, OF THE CASTLES AND TOWNS VISITED BY EDWARD L, AND OF THE BARONS, CLERGY, AND OTHERS WHO SWORE FEALTY TO ENGLAND IN 1291-6 ; ALSO OF THE ABBEY OF CUPAR AND THE PRIORY OF RESTENNETH, By the late ANDREW JERVISE, F.SA. SCOT. " DISTRICT EXAMINER OF REGISTERS ; AUTHOR OF THE LAND OF THE LINDSAYS," "EPITAPHS AND INSCRIPTIONS," ETC. REWRITTEN AND CORRECTED BY Rev. JAMES GAMMACK, M.A. Aberdeen CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES, SCOTLAND ; AND MEMBER OF THE CAMBRIAN ARCH/EOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION. *v MEMORIALS OF ANGUS and M EARNS AN ACCOUNT HISTORICAL, ANTIQUARIAN, S* TRADITIONARY. VOL. I. EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS M DCCC LXXXV TO THE EIGHT HONOURABLE 31ame& SIXTH, AND BUT FOR THE ATTAINDER NINTH, EAEL OF SOUTHESK, BARON CARNEGIE OF KINNAIRD AND LEUCHARS, SIXTH BARONET OF PITTARROW, FIRST BARON BALINHARD OF FARNELL, AND A KNIGHT OF THE MOST ANCIENT AND MOST NOBLE ORDER OF THE THISTLE, Sins Seconn tuition IN IS, ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF MANY FAVOURS, MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THE EDITOR VOL. I. EDITORS PBEFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. As the Eirst Edition of this work was evidently an object of much satisfaction to the Author, and as its authority has been recognised by its being used so freely by later writers, I have felt in preparing this Second Edition that I was acting under a weighty responsibility both to the public and to Mr. Jervise's memory. Many fields have presented themselves for independent research, but as the plan of the work and its limits belonged to the author and not to the editor, I did not feel justified in materially altering either of them. -

Beard2016.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ROB DONN MACKAY: FINDING THE MUSIC IN THE SONGS Ellen L. Beard Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2015 ABSTRACT AND LAY SUMMARY This thesis explores the musical world and the song compositions of eighteenth-century Sutherland Gaelic bard Rob Donn MacKay (1714-1778). The principal focus is musical rather than literary, aimed at developing an analytical model to reconstruct how a non-literate Gaelic song-maker chose and composed the music for his songs. In that regard, the thesis breaks new ground in at least two ways: as the first full-length study of the musical work of Rob Donn, and as the first full-length musical study of any eighteenth-century Scottish Gaelic poet. Among other things, it demonstrates that a critical assessment of Rob Donn merely as a “poet” seriously underestimates his achievement in combining words and music to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.