Paltamo Full Employment Experiment: an Application of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masters' Thesis

FACULTY OF TECHNOLOGY DEGREE PROGRAMME IN PROCESS AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MASTERS’ THESIS CIRCULAR ECONOMY AND CLOSING NUTRIENT CYCLES: PLANNING SUSTAINABLE BIO-WASTE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR PUOLANKA MUNICIPALITY Author Anusha Airi Supervisor Ph.D., M.Sc. (Tech.) Sari Piippo Advisor Doc., Prof. D.Sc. (Tech.) Eva Pongrácz January 2019 TIIVISTELMÄ Oulun yliopiston, teknillinen tiedekunta Koulutusohjelma (kandidaatintyö, diplomityö) Pääaineopintojen ala (lisensiaatintyö) Ympäristötekniikka Tekijä Työn ohjaaja yliopistolla Airi, Anusha PhD., M.Sc. (Tech) Sari Piippo Prof. Doc. D.Sc. (Tech) Eva Pongrácz Työn nimi Kiertotalous ja ravinnekiertojen sulkeminen: Kestävän biojätehuoltosysteemin kehittäminen Puolangan kunnalle Opintosuunta Työn laji Aika Sivumäärä Diplomityö Tammikuu 2019 105 s., 24 s liitetta Vesi ja ympäristö Tiivistelmä Suomen hallitus on tehnyt viiden vuoden (2018-2023) jätesuunnitelman ”Kierrätyksestä kiertotalouteen”, jonka tavoitteena on kestävä jätehuolto ja jätteiden synnyn ehkäiseminen. Kiertotalouden omaksuminen tuo mukanaan kolme positiivista asiaa: talouskasvun, sosiaalisen kehityksen ja ympäristövaikutusten pienenemisen, edeten samalla kohti kestävää kehitystä. Teoreettinen osa määrittelee ja täsmentää kiertotalouden termejä ja kuvaa sitä, miten kiertotalous on parempi kuin lineaarinen järjestelmä; kuvaa, mitä ovat teollinen ekologia, vähähiilinen talous, ravinnekierto ja ravinteiden kierron sulkemisen tärkeys, tarkastelee erilaisia lannoitetyyppejä ja syitä miksi valita luonnonlannoitteet keinolannoitteiden sijaan. -

Taloudelliset Vaikutukset: Hyrynsalmi, Kuhmo, Sotkamo Ja Suomussalmi

Matkailullisen vapaa-ajanasumisen alue- taloudelliset vaikutukset: Hyrynsalmi, Kuhmo, Sotkamo ja Suomussalmi Pekka Kauppila Matkailullisen vapaa-ajanasumisen aluetaloudelliset vaikutukset: Hyrynsalmi, Kuhmo, Sotkamo ja Suomussalmi Pekka Kauppila Kajaanin ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja B Raportteja ja selvityksiä 101 Yhteystiedot: Kajaanin Ammattikorkeakoulun kirjasto PL 240, 87101 KAJAANI Puh. 044 7157042 Sähköposti: [email protected] http://www.kamk.fi Kannen kuva: Shutterstock Kajaanin ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja B 101 / 2020 ISBN 978−952−7319−53−9 ISSN 1458−915X SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 1. JOHDANTO .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Tutkimusraportin tausta ja tarve ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Tutkimusraportin tarkoitus, tavoitteet ja viitekehys ............................................ 5 1.3 Tutkimusraportin keskeiset käsitteet .................................................................. 7 1.4 Viimeaikaisia matkailun aluetaloudellisia tutkimuksia paikallistasolta ............... 12 2. TUTKIMUSALUEET, -AINEISTOT JA -MENETELMÄT ....................................................... 15 2.1 Tutkimusalueet Suomen ja Kainuun matkailun aluerakenteessa ........................ 15 2.2 Tutkimusalueet ja vapaa-ajanasunnot: kunnittain ja matkailukeskuksittain ....... 17 2.3 Tutkimusaineistot............................................................................................. 22 2.4 Tutkimusmenetelmät -

(KDR AIM) Mining –Initiating Coverage 17 January 2019

Karelian Diamond Resources (KDR AIM) Mining –Initiating Coverage 17 January 2019 Stock Data Introduction Karelian Diamond Resources (“Karelian”) is an AIM listed diamond exploration Share Price 3.40p company operating in Finland. It acquired the Lahtojoki diamond mining concession in April 2016 from A & G Mining OY. Since then, Karelian have identified further Market Cap (£M) 1.2 diamond potential through the discovery of kimberlite boulders in till adjacent to the EV (£M) 1.3 Lahtojoki diamond deposit. In the Kuhmo area, Karelian have further defined the Seitapera pipe, the largest known kimberlite pipe in Finland which covers an area of 6.9Ha, and discovered a number of other kimberlite dykes in the vicinity. Price Chart 8.0 Diamonds in Finland 7.0 The first kimberlite in Finland was discovered in the 1960’s by Malmikaivos Oy. 6.0 Despite 50 years of exploration no diamond mine has been developed yet, despite the fact that there are two very significant diamond mines in the Russian controlled 5.0 part of the craton. Additionally, in the latest Fraser Institute survey for 2017, the top 4.0 jurisdiction for investment, based on the Investment Attractive Index was Finland. In 3.0 the Policy Perception Index, which is a “report card” to governments on the 2.0 Jan-18 Apr-18 Jul-18 Oct-18 Jan-19 attractiveness of their mining policies, Finland rated second. Valuation 52 Week Range BHC has modelled the Lahtojoki Diamond Project based on the preliminary economic assessment (“PEA”) and valued it at US$32.9M, with an IRR of 50.2%. -

Feasibility Study of Lignin Side-Flow Applications in Kainuu, Summary of Results and Recommendations

Feasibility study of lignin side-flow applications in Kainuu, summary of results and recommendations BRIDGES, 7th IPL PP2, Regional Council of Kainuu May 29th 2018, Munich, DE www.interregeurope.eu/BRIDGES 1 Lignin feasibility study summary Purpose: to identify cost efficient lignin-based investments for Kainuu region. Optimisation question: to identify optimal types of lignin applications aligned with the supply and quality potential of (primarily) Kainuu lignin suppliers & Finnish users (i.e. large businesses operating in Finland and utilising lignin). Findings: The recommendations are organised into short term and medium term options. The short term options focus on lignin production and processing investments, and the longer term options relate more to development projects. The latter includes also research and training of entrepreneurs and sector-experts. For detailed review of the recommendations. Period of implementation of the feasibility study: 1.10.2017 deciding the focus & study expectations – 30.4.2018, delivery of the final feasibility study Good practice (-s) reference: 1) Centre of Expertise Biobased Economy (COEBBE), Netherlands and 2) The Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC),Germany. Funding / financing: Structural funds, regional funds, private funds. Action plan take up: 1) Agree lignin operator in Kainuu (lignin processing) and investment terms (include FDI options); 2) Agree lignin supplier investments concept and criteria for nation-wide calls; 3) Agree the concepts of the devleopment projects and the associated -

Country Report Finland

Coping Strategies and Regional Policies – Social Capital in the Nordic Peripheries – Country report Finland Esko Lehto Nordregio 2002 Nordregio Working Paper 2002:7 ISSN 1403-2511 Nordregio - the Nordic Centre for Spatial Development PO Box 1658 S-111 86 Stockholm, Sweden Tel. +46 8 463 5400, fax: +46 8 463 54 01 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.nordregio.se Nordic co-operation takes place among the countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, as well as the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Åland. The Nordic Council is a forum for co-operation between the Nordic parliaments and governments. The Council consists of 87 parlia- mentarians from the Nordic countries. The Nordic Council takes policy initiatives and monitors Nordic co-operation. Founded in 1952. The Nordic Council of Ministers is a forum for co-operation between the Nordic governments. The Nordic Council of Ministers implements Nordic co- operation. The prime ministers have the overall responsibility. Its activities are co-ordinated by the Nordic ministers for co-operation, the Nordic Committee for co-operation and portfolio ministers. Founded in 1971. Stockholm, Sweden 2002 Preface This country report is one of five country reports (Nordregio working papers) of the research project Coping Strategies and Regional Policies, Social Capital in Nordic Peripheries. The research includes fieldwork during 2001 in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Sweden and Finland, two localities per country, two projects per locality. The project was co-operatively conducted by researchers from the University of Iceland (Reykjavik), the Research Centre on Local and Regional Development (Klaksvík, Faroes), the Swedish Agricultural University (Uppsala), the University of Joensuu (Finland) and Roskilde University (Denmark). -

Aikalisä 2021

? ? ? ? Aikalisä ? on kainuulaisille nuorille miehille tarkoitettu palvelu, jossa saat: ? ? - sinulle nimetyn, oman ohjaajan ? - tukea elämäntilanteesi selvittelyssä - apua parhaiden ratkaisujen löytämiseen - tietoa palveluista Yhdessä ohjaajan kanssa voit käydä läpi aivan tavallisia ajankohtaisia asioitasi, jotka liittyvät esimerkiksi opiskeluun, asumiseen, raha-asioihin, ihmissuhteisiin ja terveyteen. Palveluun kannattaa tulla myös, jos päihteiden käyttö mietityttää, mieltä masentaa tai olet muuten huolissasi tilanteestasi. Aikalisässä saat henkilökohtaista tukea, tietoa ja rohkaisua asioittesi hoitamiseen. Tarvittaessa saat ohjausta myös sopivien palveluiden löytämiseen. Sovit käsiteltävistä asioista ja tapaamisten määrästä oman ohjaajasi kanssa. Kaikki Aikalisä-ohjaajat ovat koulutettuja ammattilaisia. Palvelu on Aikalisä luottamuksellista ja maksutonta. elämä raiteilleen elämä raiteilleen Paltamo, Kajaani Sosiaalityöntekijä Tolonen Satu p. 044 7970086 Sosiaaliohjaaja Heikkinen Maarit p. 040-7402471 Kajaanin Aikuissosiaalityö, Välikatu 21 B, 2. krs 87100 Puolangan sos. ja terveyspalvelut, Ouluntie 13, 89200 Sosiaaliohjaaja Koskela Annu p. 044 2885303 Kajaani Puolanka Aikuissosiaalityö, Puolangantie 10, 88300 Paltamo [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kuraattori Vuorinen Tiina p. 044 5929706 Työpajaohjaaja/Etsivä nuorisotyöntekijä Pirjo Holappa Kuraattori Rautio Sirpa p. 044 7500650 Kainuun ammattiopisto, Vuorikatu 2, 87100 Kajaani p. 0407177248 Paltamon kunta, Lampitie 2, 88300 Paltamo [email protected] -

Palveluopaskansi VILLE.Pdf 1 17.5.2016 14:05:15

kainuun_sote_palveluopaskansi_VILLE.pdf 1 17.5.2016 14:05:15 Julkinen tiedote1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Palveluopas Kainuun sote 2 Terveyttä ja hyvinvointia vauvasta vaariin Yhteystiedot Kainuun sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon Kainuun sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon kuntayhtymä tuottaa jäsenkunnilleen kaikki kuntayhtymä (Kainuun sote) sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut. Postiosoite Jäsenkunnat ovat Hyrynsalmi, Kajaani, PL 400, 87070 Kainuu Kuhmo, Paltamo, Ristijärvi, Sotkamo ja Laskutusosoite Suomussalmi. Ostolaskut, PL 401, 87070 Kainuu Käyntiosoite (hallinto) Puolangan kunta on kuntayhtymän osa- Pohjolankatu 13, 3. krs, Kajaani jäsen. Kainuun sote tuottaa Puolangalle Sähköposti erikoissairaanhoidon, kehitysvammahuol- [email protected] lon erityishuoltopiirin, eläinlääkintähuollon Puhelinvaihde ja ympäristöterveydenhuollon palvelut. 08 61561 Kirjaamo avoinna ma–pe klo 8.00–15.00 faksi 08 6155 4270 [email protected] Kainuun sote verkossa sote.kainuu.fi facebook.com/kainuunsote Twitter: @Kainuunsote YouTube: Kainuun sote Julkaisija Kainuun sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon kuntayhtymä Painopaikka Juvenes Print Kansikuva Pohjolan Mylly 3 LUKIJALLE Kainuun sote on tuottanut vuodesta 2013 lähtien kaikki sosiaali- ja terveyden- huollon palvelut Hyrynsalmen, Kajaanin, Kuhmon, Paltamon, Ristijärven, Sotka- mon ja Suomussalmen asukkaille. Puolangalla Kainuun sote vastaa ensihoidosta ja erikoissairaanhoidosta, kehitysvammahuollosta ja ympäristöterveydenhuollos- ta (esim. eläinlääkärit). Kainuun sotella on yhteensä 3 700 työntekijää, ja se on maakunnan -

ESPON PROFECY D5 Annex 17. 10 Additional

PROFECY – Processes, Features and Cycles of Inner Peripheries in Europe (Inner Peripheries: National territories facing challenges of access to basic services of general interest) Applied Research Final Report Annex 17 Brief Overview of 10 IP Regions in Europe Version 07/12/2017 This applied research activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Paulina Tobiasz-Lis, Karolina Dmochowska-Dudek, Marcin Wójcik, University of Lodz, (Poland) Mar Ortega-Reig, Hèctor del Alcàzar, Joan Noguera, Institute for Local Development, University of Valencia (Spain) Andrew Copus, Anna Berlina, Nordregio (Sweden) Francesco Mantino, Barbara Forcina, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (Italy) Sabine Weck, Sabine Beißwenger, Nils Hans, ILS Dortmund (Germany) Gergely Tagai, Bálint Koós, Katalin Kovács, Annamária Uzzoli, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (Hungary) Thomas Dax, Ingrid Machold, Federal Institute for Less Favoured and Mountainous Areas (BABF) (Austria) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Barbara Acreman and Zaira Piazza (Italy), Eedi Sepp (Estonia), Zsolt Szokolai, European Commission. ESPON EGTC: Marjan van Herwijnen (Project Expert), Laurent Frideres (HoU E&O), Ilona Raugze (Director), Piera Petruzzi (Outreach), Johannes Kiersch (Financial Expert). Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. -

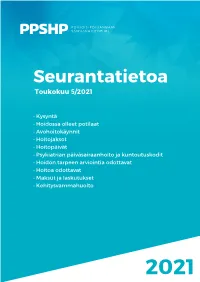

Seurantatietoa 5/2021

Seurantatietoa Toukokuu 5/2021 • Kysyntä • Hoidossa olleet potilaat • Avohoitokäynnit • Hoitojaksot • Hoitopäivät • Psykiatrian päiväsairaanhoito ja kuntoutuskodit • Hoidon tarpeen arviointia odottavat • Hoitoa odottavat • Maksut ja laskutukset • Kehitysvammahuolto 2021 Kysyntä (esh) jäsenkunnittain tammi-toukokuussa 2020-2021 (lähetteet, ilman lähetettä saapuneet ja sähköiset konsultaatiovastaukset) Muutos kpl 56,2 Merijärvi 77 39,7 Sievi 192 39,7 Oulainen 506 37,6 Ylivieska 702 27,4 Hailuoto 52 20,6 Kalajoki 220 Alavieska 19,0 60 Haapavesi 18,4 227 Haapajärvi 18,3 215 Pyhäntä 17,4 42 Pyhäjärvi 14,9 139 Ii 14,5 221 Oulu 13,0 4 354 Jäsenkunnat 12,9 7 983 Kärsämäki 12,7 58 Utajärvi 12,4 51 Kempele 11,0 321 Kuusamo 10,5 153 Nivala 9,5 133 Liminka 9,2 132 Muhos 5,3 84 Siikajoki 4,4 25 Siikalatva 3,6 22 Tyrnävä 3,4 32 Pudasjärvi 1,5 22 Raahe 1,1 31 Taivalkoski 0,5 3 Pyhäjoki -2,5 -9 Lumijoki -8,8 -26 Vaala -9,3 -56 Peruspalv.ky Kallio 26,7 1 087 Kalajoen yt-alue 24,7 297 Sos. ja terv.piiri Helmi 18,2 269 Peruspalv.ky Selänne 16,7 354 Oulunkaaren ky 5,9 238 Raahen seud.hyvinv.ky 1,2 47 -30 -10 10 30 50 70 Muutos (%) Hoidossa olleiden potilaiden (erikoissairaanhoidon eri henkilöt) määrän muutos tammi-toukokuussa 2020-2021 Muutos kpl Merijärvi 26,7 54 Sievi 20,2 125 Ylivieska 19,5 489 Alavieska 17,3 67 Oulainen 16,3 262 Pyhäntä 10,7 30 Kalajoki 10,4 132 Kuusamo 9,9 159 Ii 8,8 172 Nivala 8,4 149 Kärsämäki 8,1 41 Haapajärvi 7,8 103 Oulu 6,7 2 777 Jäsenkunnat 6,5 4 953 Haapavesi 6,2 89 Kempele 5,8 219 Liminka 5,7 107 Pyhäjärvi 5,6 60 Pudasjärvi 4,3 73 Tyrnävä 3,2 41 Taivalkoski 3,2 20 Muhos 2,7 49 Utajärvi 0,2 1 Vaala -1,8 -12 Siikajoki -2,6 -21 Raahe -3,2 -122 Siikalatva -3,3 -29 Lumijoki -5,7 -21 Pyhäjoki -8,4 -42 Hailuoto -8,5 -22 Peruspalv.ky Kallio 15,7 830 Kalajoen yt-alue 12,7 186 Sos. -

FOOTPRINTS in the SNOW the Long History of Arctic Finland

Maria Lähteenmäki FOOTPRINTS IN THE SNOW The Long History of Arctic Finland Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12 / 2017 Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12/2017 Maria Lähteenmäki Footprints in the Snow The Long History of Arctic Finland Info boxes: Sirpa Aalto, Alfred Colpaert, Annette Forsén, Henna Haapala, Hannu Halinen, Kristiina Kalleinen, Irmeli Mustalahti, Päivi Maria Pihlaja, Jukka Tuhkuri, Pasi Tuunainen English translation by Malcolm Hicks Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki 2017 Prime Minister’s Office ISBN print: 978-952-287-428-3 Cover: Photograph on the visiting card of the explorer Professor Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Taken by Carl Lundelius in Stockholm in the 1890s. Courtesy of the National Board of Antiquities. Layout: Publications, Government Administration Department Finland 100’ centenary project (vnk.fi/suomi100) @ Writers and Prime Minister’s Office Helsinki 2017 Description sheet Published by Prime Minister’s Office June 9 2017 Authors Maria Lähteenmäki Title of Footprints in the Snow. The Long History of Arctic Finland publication Series and Prime Minister’s Office Publications publication number 12/2017 ISBN (printed) 978-952-287-428-3 ISSN (printed) 0782-6028 ISBN PDF 978-952-287-429-0 ISSN (PDF) 1799-7828 Website address URN:ISBN:978-952-287-429-0 (URN) Pages 218 Language English Keywords Arctic policy, Northernness, Finland, history Abstract Finland’s geographical location and its history in the north of Europe, mainly between the latitudes 60 and 70 degrees north, give the clearest description of its Arctic status and nature. Viewed from the perspective of several hundred years of history, the Arctic character and Northernness have never been recorded in the development plans or government programmes for the area that later became known as Finland in as much detail as they were in Finland’s Arctic Strategy published in 2010. -

Summary Repor T the Lentiira Diamond Prospect, Eastern Finland

Summary Repor t The Lentiira Diamond Prospect, Eastern Finland Contents Summary 1 Introduction 2 General Diamond exploration in Finlan d The Lentiira Prospect 5 Location and Access 5 Physical features 5 Titles 5 Geological Outline 8 Bedrock Geology 8 Quaternary Geology 1 0 Sampling and Processing 1 0 Results 1 1 Conclusions and Recommendations 1 6 Reports and publications relevant to the Lentiira region 1 8 List of Appendices 20 SUMMARY The Lentiira Diamond Prospect is located in eastern Finland, 50 km north of the town o f Kuhmo, in an area of ready access and good infrastructure . The prospect consists of several claim reservations totalling up to about 80 km2 . The local bedrock comprises Late Archean plutonic rocks, some remnants of greenschists, and abundant Paleoproterozoic hypabyssal mafi c dikes . Quaternary cover includes one till bed up to a few metres thick and locally glacial outwash, sand and gravel . The area has low relief and between drumlins and moraine hillock s the ground may be swampy. Climate is continental with a mean temperature of +1 °C . Winters are rather cold and snow cover may exceed one metre . Snow cover stays in open areas some 190 days per year and frost may penetrate the till down to nearly 2 metres . The Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) has been carrying out regional heavy minerals studies on Quaternary sediments since 1992. The Lentiira Prospect is the first discovery site of kimberlitic indicator minerals from this regional study where a more detailed till sampling ha s been completed. The detailed investigation comprises some 50 surficial and basal till samples . -

OULUJOEN HISTORIAA Vaala – Nuojua Ulkoilureitti

OULUJOEN HISTORIAA Vaala – Nuojua ulkoilureitti LUMMAN LENKKI Reittiesite Oulujoki Oulujoki muodostaa alimman osan Oulujoen vesistöstä. Vesistö jakautuu kahtia Oulujärven kohdalla, joka on Suomen neljänneksi suurin järvi. Oulujär- veen vesiä tuovat Hyrynsalmen ja Sotkamon reittivedet sekä muutama vähäi- sempi joki. Oulujärvestä vedet purkautuvat Vaalankurkun kautta Oulujokeen, joka laskee lopulta Oulun kaupungin halki Perämereen. Pituutta joella on 106 km ja kor- keuseroa 122 metriä. Oulujokeen laskee neljä isompaa sivujokea, jotka ovat ylhäältä lukien: Kutu-, Utos-, Muhos- ja Sanginjoki. Luonnontilainen Oulujoki oli kuuluisa koskistaan. Kuuluisin koskista oli Pyhä- koski, joka oli 17 kilometriä pitkä ja putouskorkeutta sillä oli 56 metriä. Pyhä- koski on ollut Suomen korkein ja pisin koski. Oulujoen ylin koskijakso Vaalas- sa, Niskakoski, puolestaan putosi 31 metriä yhdeksän kilometrin matkalla ja- kautuen seitsemään erilliskoskeen: Kauko, Jylhämä (kuvassa), Siitari, Oter- ma, Pyterä, Kovera ja Nuojua. Koskenlasku Oulujoen hurjien koskien pärskeissä oli monella turistilla matkan kohokohta. Nyt Oulujoen mahtavat kosket on kesytetty vesivoimalaitosten avulla. 1 Kalaisa Oulujoki houkutteli asutusta jo kivikauden aikana. Myöhemminkin se on tarjonnut leipää alueen ihmisille monella eri tavalla. Tärkeitä elinkeinoja ovat olleet esimerkiksi kalastus, uitto ja tervasoutu. Myös tervanpolttoa ja rau- taruukkitoimintaa on koskivoimalla harjoitettu. Lohi on houkutellut urheiluka- lastajia Oulujoen koskille jo 1800-luvulla, joten matkailuelinkeinonkin juuret ovat täällä syvällä. Oulujoen koskien rakentamisen myötä moni asia on muut- tunut. Asutus Oulujoella Asutus alkoi n. 8800-8000 vuotta sitten niillä alueilla, jotka siihen mennessä olivat ehtineet kohota jääkauden jälkeen merestä. Oulujokivarren kivikautisis- ta löydöistä suurin osa on tehty Vaalan kunnan alueella: asuinpaikkoja on löydetty noin 50 ja kiviesineitä lähes 500. Kivikaudella asuinpaikka valittiin veden luota, mutta ei mielellään aavan ulapan ääreltä.