Rabbi Shlomo Goren and the Military Ethic of the Israel Defense Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holy War in Modern Judaism? "Mitzvah War" and the Problem of the "Three Vows" Author(S): Reuven Firestone Source: Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol

Holy War in Modern Judaism? "Mitzvah War" and the Problem of the "Three Vows" Author(s): Reuven Firestone Source: Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 74, No. 4 (Dec., 2006), pp. 954- 982 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4139958 Accessed: 18-08-2018 15:51 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Academy of Religion This content downloaded from 128.95.104.66 on Sat, 18 Aug 2018 15:51:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Holy War in Modern Judaism? "Mitzvah War" and the Problem of the "Three Vows" Reuven Firestone "Holy war," sanctioned or even commanded by God, is a common and recurring theme in the Hebrew Bible. Rabbinic Judaism largely avoided discussion of holy war for the simple reason that it became dangerous and self-destructive. The failed "holy wars" of the Great Revolt and the Bar Kokhba Rebellion eliminated enthusiasm for it among the survivors engaged in reconstructing Judaism from ancient biblical religion. The rabbis therefore built a fence around the notion through two basic strat- egies: to define and categorize biblical wars so that they became virtually unthinkable in their contemporary world and to construct a divine con- tract between God, the Jews, and the world of the Gentiles that would establish an equilibrium preserving the Jews from overwhelming Gentile wrath by preventing Jewish actions that could result in war. -

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness As a Religious Value

Source Sheet for Zvi Zohar’s presentation at Valley Beit Midrash Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness as a Religious Value Women Background: Chapter 31 of the Biblical book of Proverbs is a song of praise to the “Woman of Valor” (Eshet Hayyil). Inter alia, the Biblical author writes of the Eshet Hayyil: She is clothed in strength and glory, and smiles when contemplating the last day. She opens her mouth in wisdom, and instruction of grace is on her tongue… Her children rise up, and call her blessed; her husband praises her: 'Many daughters have done valiantly, but you are most excellent of them all.' Grace is deceitful, and beauty is vain; but a woman that feareth the LORD, she shall be praised. Give her of the fruits of her hands; and let her works praise her in the gates. Rabbi Israel Ya’akov AlGhazi (d. 1756) was born in Izmir and moved to Jerusalem, where he was subsequently chosen to be chief rabbi. His exposition of Eshet Hayyil is presented at length by his son, rabbi Yomtov AlGhazi, 1727-1802 (who was in his turn also chief rabbi of Jerusalem), in the homiletic work Yom Tov DeRabbanan, Jerusalem 1843. The following is a significant excerpt from that text: Text: And this is what is meant by the verse “She is clothed in strength and glory” – that she clothed herself in tefillin and tallit that are called1 “strength and glory”. And scripture also testifies about her, that she “smiles when contemplating the last day”, i.e., her reward on “the last day” – The World-To-Come – is assured. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug. 18 at 11:00 AM EDT Course Description: In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook delivered a fiery address criticizing the modern state of Israel for what he viewed as its founding sin: accepting the Partition Plan and dividing the Land of Israel. “Where is our Hebron?” he cried out. “Where is our Shechem, our Jericho… Have we the right to give up even one grain of the Land of God?” Just three weeks later, the Six Day War broke out, and the Israeli army conquered the biblical heartlands that Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda had mourned—in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. Hebron, Shechem, and Jericho were returned to Jewish sovereignty. In the aftermath of the war, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda’s words seemed almost prophetic. His spiritual vision laid the foundation for a new generation of religious Zionism and the modern settler movement, and his ideology continues to have profound implications for contemporary Israeli politics. In this session, we will explore Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook’s 1967 speech, his teachings, and his critics— particularly Rabbi Yehuda Amital. Guiding Questions: 1. How does Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook interpret the quotation from Psalm 107: "They have seen the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep"? Why do you think he begins this speech with this scripture? 2. In the section, "They Have Divided My Land," Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook tells two stories about responses to partition. Based on these stories, what do you think is his attitude toward diplomacy and politics is? 1 of 13 tikvahonlineacademy.org/ 3. -

An Old/New Anti-Semitism

בס“ד Parshat Vayera 15 Cheshvan, 5778/November 4, 2017 Vol. 9 Num. 9 This week’s Toronto Torah is dedicated by Rabbi Charles and Lori Grysman Bernie Goldstein z”l ,דב בן גרשון ,for the shloshim of Lori’s father An Old/New Anti-Semitism Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner In 2004, then-MK Natan Sharansky (26:18-19), they suggested that Yitzchak was not a true heir to described a “New Anti-Semitism”: anti- Yishmael shot arrows at his baby Avraham. She responded by insisting Jewish activism which disguises itself brother, pretending that it was only a that Yishmael be evicted; onlookers as political opposition to the State of joke. Since Yishmael posed a mortal would expect that Avraham would not Israel. A central characteristic of this threat to his brother, Sarah ordered him evict his biological child in order to school is delegitimization – claiming evicted. (Bereishit Rabbah ibid.) protect the reputation of his stepchild. that we lack the right to our Israeli homeland. However, Rabbi Naftali Zvi Finally, our Sages offered a third Per Netziv, Sarah exiled Yishmael Yehuda Berlin (“Netziv”) contended approach, relying not so much on the because he threatened the identity of more than a century ago that word mitzachek as on Sarah’s Yitzchak, and his heirs, as members of delegitimization is not new. Rather, it statement, “This maid’s son will not Avraham’s family. This was the original dates back to the first biblical enemy inherit with my son, with case of “New Anti-Semitism”, an attempt of the Jewish people: Yishmael. Yitzchak.” (Bereishit 21:10) Yishmael to delegitimize the Jews’ claim to the laughed at Yitzchak, saying, “Fools! I mantle of our ancestors. -

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak Hacohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption*

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak HaCohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption* Judith Winther Copenhagen Religious Zionism—Between Messsianism and A-Messianism Until the 19th century and, to a certain ex- tute a purely human form of redemption for a tent, somewhat into the 20th, most adherents redeemer sent by God, and therefore appeared of traditional, orthodox Judaism were reluc- to incite rebellion against God. tant about, or indifferent towards, the active, Maimonides' active, realistic Messianism realistic Messianism of Maimonides who averr- was, with subsequent Zionist doctrines, first ed that only the servitude of the Jews to foreign reintroduced by Judah Alkalai, Sephardic Rab- kings separates this world from the world to bi of Semlin, Bessarabia (1798-1878),3 and Zwi come.1 More broadly speaking, to Maimonides Hirsch Kalisher, Rabbi of Thorn, district of the Messianic age is the time when the Jewish Poznan (1795-1874).4 people will liberate itself from its oppressors Both men taught that the Messianic pro- to obtain national and political freedom and cess should be subdivided into a natural and independence. Maimonides thus rejects those a miraculous phase. Redemption is primari- Jewish approaches according to which the Mes- ly in human hands, and redemption through a sianic age will be a time of supernatural qual- miracle can only come at a later stage. They ities and apocalyptic events, an end to human held that the resettling and restoration of the history as we know it. land was athalta di-geullah, the beginning of Traditional, orthodox insistence on Mes- redemption. They also maintained that there sianism as a passive phenomenon is related to follows, from a religious point of view, an obli- the rabbinic teaching in which any attempt to gation for the Jews to return to Zion and re- leave the Diaspora and return to Zion in order build the country by modern methods. -

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE of ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. in This

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE OF ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. In this Law -- "the Council " means the Council of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel; "town rabbi" means a person serving as a town rabbi after being elected under town rabbis' elections regulations made in pursuance of the Jewish Definitions. Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971(1), and a person serving as a town rabbi whose name is included in a list of town rabbis to be published by the Minister of Religious Affairs within sixty days from the date of the coming into force of this Law. 2. The functions of the Council are - (1) the giving of responsa and opinions on matters of halacha (religious law) to persons seeking its advice; (2) activities aimed at bringing the public closer to the values of tora (religious learning) and mitzvot (religious duties); (3) the issue of certificates of ritual fitness (kashrut) (hekhsher certificates); Functions of (4) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a dayan (judge of a religious Council. court) under the Dayanim Law, 5715-1955(2); (5) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a town rabbi under town rabbis' elections regulations made in persuance of the Jewish Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971; (6) the conferment upon a rabbi of eligibility to serve as a rabbi and marriage registrar; (7) any act required for the carrying out of its functions under any law. Place of sitting of 3. The place of sitting of the Council shall be in Jerusalem. Council. 4. (a) The following are the members of the Council: o (1) the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, one a Sephardi, called Rishon Le- Zion, the other an Ashkenazi; they shall be elected in direct, secret and personal elections by an assembly of rabbis and representatives of Composition the public (hereinafter referred to as "the Electoral Assembly"); of Council. -

Maran Harav Ovadia the Making of an Iconoclast, Tradition 40:2 (2007)

Israel’s Chief Rabbis II: Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu R’ Mordechai Torczyner - [email protected] A Brief Biography (continued) 1. Rabbi Yehuda Heimowitz, Maran Harav Ovadia At a reception for Harav Ovadia at the home of Israel’s president attended by the Cabinet and the leaders of the military, President Zalman Shazar and Prime Minister Golda Meir both urged the new Rishon LeZion to find some way for the Langer children to marry. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was particularly open about the government’s expectations, declaring, “I don’t care how you find a heter, the bottom line is that we have to rule leniently for those who were prevented from marrying.” By the time Harav Ovadia rose to address the crowd, the atmosphere in the room had grown tense, and it seemed at first that he would capitulate and guarantee to provide the solution they sought. His opening words were: “I am from a line of Rishon LeZions dating back more than 300 years,” he began, “all of whom worked with koha d’heteira to try to solve halachic issues that arose.” But before anyone could misinterpret his words, Harav Ovadia declared, “However, halacha is not determined at Dizengoff Square; it is determined in the beit midrash and by the Shulhan Aruch. If there is any way to be lenient and permit something, the Sephardic hachamim will be the first ones to rule leniently. But if there is no way to permit something, and after all the probing, investigating, and halachic examination that we do, we still cannot find a basis to allow it, we cannot permit something that is prohibited, Heaven forbid.”… On November 15, exactly one month after their election, Harav Ovadia felt that he had no choice but to report to the press that his Ashkenazi counterpart had issued an ultimatum four days earlier: If Harav Ovadia would not join him on a new three-man beit din, Chief Rabbi Goren would cut off all contact with him and refuse to participate in a joint inaugural ceremony. -

Parshat Beshalach

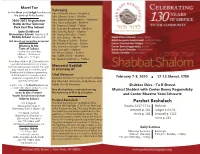

Mazel Tov Yahrzeits to the Dror and Sedgh families on Mrs. Marcelle Faust - Husband the birth of Mika Rachel. Mrs. Marion Gross - Mother 2020-2021 Registration Mrs. Batya Kahane Hyman - Husband Rabbi Arthur Schneier Mrs. Rose Lefkowitz - Brother Mr. Seymour Siegel - Father Park East Day School Mr. Leonard Brumberg - Mother Early Childhood Mrs. Ginette Reich - Mother Elementary School: Grades 1-5 Mr. Harvey Drucker - Father Middle School: Grades 6-8 Mr. Jack Shnay - Mother Ask about our incentive program! Mrs. Marjorie Schein - Father Mr. Andrew Feinman - Father Mommy & Me Mrs. Hermine Gewirtz - Sister Taste of School Mrs. Iris Lipke - Mother Tuesday and Thursday Mr. Meyer Stiskin - Father 9:00 am - 10:30 am or 10:45 am - 12:15 pm Ms. Judith Deich - Mother Mr. Joseph Guttmann - Father Providing children 14-23 months with a wonderful introduction to a more formal learning environment. Through Memorial Kaddish play, music, art, movement, and in memory of Shabbat and holiday programming, children learn to love school and Ethel Kleinman prepare to separate from their beloved mother of our devoted members February 7-8, 2020 u 12-13 Shevat, 5780 parents/caregivers. Elly (Shaindy) Kleinman, Leah Zeiger and Register online at ParkEastDaySchool.org Rabbi Yisroel Kleinman. Shabbat Shira - Tu B’Shevat or email [email protected] May the family be comforted among Musical Shabbat with Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Leon & Gina Fromer the mourners of Zion & Jerusalem. Youth Enrichment Center and Cantor Maestro Yossi Schwartz Hebrew School Parshat Beshalach Pre-K (Age 4) This Shabbat is known as Shabbat Shira Parshat Beshalach Kindergarten (Age 5) because the highlight of the Torah Reading Exodus 13:17-17:16 Haftarah Elementary School (Ages 6-12) is the Song at the Sea. -

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial Party Leader Or a Social Revolutionary? - National Israel News | Haaretz

10/8/13 Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial party leader or a social revolutionary? - National Israel News | Haaretz SUBSCRIBE TO HAARETZ DIGITAL EDITIONS TheMarker Café ISRAEL MINT עכבר העיר TheMarker הארץ Haaretz.com Jewish World News Hello Desire Pr ofile Log ou t Do you think I'm You hav e v iewed 1 of 10 articles. subscri be now sexy? Esquire does Search Haaretz.com Tuesday, October 08, 2013 Cheshvan 4, 5774 NEWS OPINION JEWISH WORLD BUSINESS TRAVEL CULTURE WEEKEND BLOGS ARCHAEOLOGY NEWS BROADCAST ISRAEL NEWS Rabbi Ovadia Y osef World Bank report Israel's brain drain Word of the Day Syria Like 83k Follow BREAKING NEWS 1:3219 PM Anbnoouut n10c eSmyerinatn osf t Nryo tboe cl rpohsyss oicvse pr rbizoer dlaeur rfeantcee d ienltaoy Iesdr,a nelo ( Hdeataarielstz g)iven (AP) More Breaking News Home New s National Analysis || Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: Sectorial party leader or HAARETZ SELECT a social revolutionary? To see the greatness of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, one must look separately at Ovadia A and Ovadia B. By Yair Ettinger | Oct. 8, 2013 | 9:03 AM | 1 7 people recommend this. Be the first of your 1 Tw eet 3 Recommend Send friends. The Israel Air Force flyover at Auschwitz: A crass, superficial display Why the Americans could not hav e bombed the death camp until July 1 944, and why the 2003 fly ov er there was a mistake. A response to Ari Shav it. By Yehuda Bauer | Magazine On Twitter, nothing is sacred - not even Rabbi Ovadia Yosef By Allison Kaplan Sommer | Routine Emergencies Ary eh Deri, (L), a political kingmaker and head of Shas, holding the hand of the party 's spiritual leader, Rabbi Ov adia Yosef in 1 999. -

From the Rabbi's Study

Volume 31Page Issue 4 June 2017 - Sivan 5777 The Shaliach The Shaliach News and Views from the Young Israel of Plainview F ROM THE R ABBI’ S S TUDY Yom Haatzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim1 Only a few weeks ago we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the reunification of the Holy City, Jerusalem. Yom Yerushalayim recalls a moment in history that touched every Jewish soul. In a biblical reversal of fortunes, Gamel Abdel Nasser’s plans and threat expressed by the united Arab armies to throw the Jews into the sea were replaced by an epochal victory that brought about the solidification of the state of Israel and control over the Western Wall and the old city INSIDE THIS ISSUE: of Jerusalem. The list of endearing images -- paratroopers wailing at the Western Wall, Israelis of all stripes linking hands to dance in the streets, of Abba Eban’s great defense of the Jewish state at the United Nations, Moshe Dayan’s solemn walk to the Kotel, Rav Shlomo Goren’s sho- far blow - is endless. Rabbi’s Study 1, 8 The six day war inspired Yom Yerushalayim, a holiday to counterpart with Yom Haatzmaut, the celebration of Israel’s independence. Interestingly, the history of contemporary Israel, where sovereignty arrived before Jerusalem, mirrors the founding of Ancient Israel. Joshua Committee Directory 2 conquered the lands between the Mediterranean and the Jordan to carve out a home for the Isra- elite and only generations later did King David declare Jerusalem as the capital city. President’s Pen 3 Maimonides (Temple Laws, Chapter 6) notes that what we are dealing with here are not only different historical moments, but divergent holinesses.