Chabad V. Russian Federation and Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness As a Religious Value

Source Sheet for Zvi Zohar’s presentation at Valley Beit Midrash Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness as a Religious Value Women Background: Chapter 31 of the Biblical book of Proverbs is a song of praise to the “Woman of Valor” (Eshet Hayyil). Inter alia, the Biblical author writes of the Eshet Hayyil: She is clothed in strength and glory, and smiles when contemplating the last day. She opens her mouth in wisdom, and instruction of grace is on her tongue… Her children rise up, and call her blessed; her husband praises her: 'Many daughters have done valiantly, but you are most excellent of them all.' Grace is deceitful, and beauty is vain; but a woman that feareth the LORD, she shall be praised. Give her of the fruits of her hands; and let her works praise her in the gates. Rabbi Israel Ya’akov AlGhazi (d. 1756) was born in Izmir and moved to Jerusalem, where he was subsequently chosen to be chief rabbi. His exposition of Eshet Hayyil is presented at length by his son, rabbi Yomtov AlGhazi, 1727-1802 (who was in his turn also chief rabbi of Jerusalem), in the homiletic work Yom Tov DeRabbanan, Jerusalem 1843. The following is a significant excerpt from that text: Text: And this is what is meant by the verse “She is clothed in strength and glory” – that she clothed herself in tefillin and tallit that are called1 “strength and glory”. And scripture also testifies about her, that she “smiles when contemplating the last day”, i.e., her reward on “the last day” – The World-To-Come – is assured. -

Observance, Celebration of Historic Torah Spills Into

CHABAD COMMUNITY CENTER For Jewish Life And Learning Dec. 2008 Issue 3 Kislev 5769 IN YOUR WORDS DOORS OPEN TO NEW HOME “I hope that (Chabad) continues to ... challenge DURING MOMENTOUS AFFAIR the community to be Labels of Ortho- more spiritual and dox, Conservative more involved with its and Reform were left at the door on historical roots.” Sept. 7 when people RICK BLACK streamed in through the physical thresh- old of the new “(The event) was Chabad Community Center for Jewish one more chance to Life and Learning party and pray, and and through the really appreciate the spiritual threshold of an idea a decade significance of the Torah.” in the making. DR. PAUL SILVERSTEIN That day, there was FR OM L eft , Att O R N E Y GE N era L Dre W EDMOND S ON , RA BBI an incredible mixture YE H U D A WE G , Larr Y DA VI S , RA BBI YE H U D A KR IN S KY , RA BBI of people from all dif- OV A DI A GOLDM A N A ND RICH ar D TA N E NB au M C ut T H E R IBBON ferent backgrounds T O U NV E IL T H E CH A B A D COMM U NI T Y CE N ter . “Let’s not take for who were genuinely granted ... our Chabad happy to celebrate the for the future. And the hot very warm, almost like a Center here and our building’s grand opening, sun aside, there was a per- glowing shine on people’s Rabbi Ovadia Goldman vading sense of warmth faces. -

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug. 18 at 11:00 AM EDT Course Description: In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook delivered a fiery address criticizing the modern state of Israel for what he viewed as its founding sin: accepting the Partition Plan and dividing the Land of Israel. “Where is our Hebron?” he cried out. “Where is our Shechem, our Jericho… Have we the right to give up even one grain of the Land of God?” Just three weeks later, the Six Day War broke out, and the Israeli army conquered the biblical heartlands that Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda had mourned—in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. Hebron, Shechem, and Jericho were returned to Jewish sovereignty. In the aftermath of the war, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda’s words seemed almost prophetic. His spiritual vision laid the foundation for a new generation of religious Zionism and the modern settler movement, and his ideology continues to have profound implications for contemporary Israeli politics. In this session, we will explore Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook’s 1967 speech, his teachings, and his critics— particularly Rabbi Yehuda Amital. Guiding Questions: 1. How does Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook interpret the quotation from Psalm 107: "They have seen the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep"? Why do you think he begins this speech with this scripture? 2. In the section, "They Have Divided My Land," Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook tells two stories about responses to partition. Based on these stories, what do you think is his attitude toward diplomacy and politics is? 1 of 13 tikvahonlineacademy.org/ 3. -

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak Hacohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption*

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak HaCohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption* Judith Winther Copenhagen Religious Zionism—Between Messsianism and A-Messianism Until the 19th century and, to a certain ex- tute a purely human form of redemption for a tent, somewhat into the 20th, most adherents redeemer sent by God, and therefore appeared of traditional, orthodox Judaism were reluc- to incite rebellion against God. tant about, or indifferent towards, the active, Maimonides' active, realistic Messianism realistic Messianism of Maimonides who averr- was, with subsequent Zionist doctrines, first ed that only the servitude of the Jews to foreign reintroduced by Judah Alkalai, Sephardic Rab- kings separates this world from the world to bi of Semlin, Bessarabia (1798-1878),3 and Zwi come.1 More broadly speaking, to Maimonides Hirsch Kalisher, Rabbi of Thorn, district of the Messianic age is the time when the Jewish Poznan (1795-1874).4 people will liberate itself from its oppressors Both men taught that the Messianic pro- to obtain national and political freedom and cess should be subdivided into a natural and independence. Maimonides thus rejects those a miraculous phase. Redemption is primari- Jewish approaches according to which the Mes- ly in human hands, and redemption through a sianic age will be a time of supernatural qual- miracle can only come at a later stage. They ities and apocalyptic events, an end to human held that the resettling and restoration of the history as we know it. land was athalta di-geullah, the beginning of Traditional, orthodox insistence on Mes- redemption. They also maintained that there sianism as a passive phenomenon is related to follows, from a religious point of view, an obli- the rabbinic teaching in which any attempt to gation for the Jews to return to Zion and re- leave the Diaspora and return to Zion in order build the country by modern methods. -

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE of ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. in This

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE OF ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. In this Law -- "the Council " means the Council of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel; "town rabbi" means a person serving as a town rabbi after being elected under town rabbis' elections regulations made in pursuance of the Jewish Definitions. Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971(1), and a person serving as a town rabbi whose name is included in a list of town rabbis to be published by the Minister of Religious Affairs within sixty days from the date of the coming into force of this Law. 2. The functions of the Council are - (1) the giving of responsa and opinions on matters of halacha (religious law) to persons seeking its advice; (2) activities aimed at bringing the public closer to the values of tora (religious learning) and mitzvot (religious duties); (3) the issue of certificates of ritual fitness (kashrut) (hekhsher certificates); Functions of (4) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a dayan (judge of a religious Council. court) under the Dayanim Law, 5715-1955(2); (5) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a town rabbi under town rabbis' elections regulations made in persuance of the Jewish Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971; (6) the conferment upon a rabbi of eligibility to serve as a rabbi and marriage registrar; (7) any act required for the carrying out of its functions under any law. Place of sitting of 3. The place of sitting of the Council shall be in Jerusalem. Council. 4. (a) The following are the members of the Council: o (1) the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, one a Sephardi, called Rishon Le- Zion, the other an Ashkenazi; they shall be elected in direct, secret and personal elections by an assembly of rabbis and representatives of Composition the public (hereinafter referred to as "the Electoral Assembly"); of Council. -

Maran Harav Ovadia the Making of an Iconoclast, Tradition 40:2 (2007)

Israel’s Chief Rabbis II: Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu R’ Mordechai Torczyner - [email protected] A Brief Biography (continued) 1. Rabbi Yehuda Heimowitz, Maran Harav Ovadia At a reception for Harav Ovadia at the home of Israel’s president attended by the Cabinet and the leaders of the military, President Zalman Shazar and Prime Minister Golda Meir both urged the new Rishon LeZion to find some way for the Langer children to marry. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was particularly open about the government’s expectations, declaring, “I don’t care how you find a heter, the bottom line is that we have to rule leniently for those who were prevented from marrying.” By the time Harav Ovadia rose to address the crowd, the atmosphere in the room had grown tense, and it seemed at first that he would capitulate and guarantee to provide the solution they sought. His opening words were: “I am from a line of Rishon LeZions dating back more than 300 years,” he began, “all of whom worked with koha d’heteira to try to solve halachic issues that arose.” But before anyone could misinterpret his words, Harav Ovadia declared, “However, halacha is not determined at Dizengoff Square; it is determined in the beit midrash and by the Shulhan Aruch. If there is any way to be lenient and permit something, the Sephardic hachamim will be the first ones to rule leniently. But if there is no way to permit something, and after all the probing, investigating, and halachic examination that we do, we still cannot find a basis to allow it, we cannot permit something that is prohibited, Heaven forbid.”… On November 15, exactly one month after their election, Harav Ovadia felt that he had no choice but to report to the press that his Ashkenazi counterpart had issued an ultimatum four days earlier: If Harav Ovadia would not join him on a new three-man beit din, Chief Rabbi Goren would cut off all contact with him and refuse to participate in a joint inaugural ceremony. -

Parshat Beshalach

Mazel Tov Yahrzeits to the Dror and Sedgh families on Mrs. Marcelle Faust - Husband the birth of Mika Rachel. Mrs. Marion Gross - Mother 2020-2021 Registration Mrs. Batya Kahane Hyman - Husband Rabbi Arthur Schneier Mrs. Rose Lefkowitz - Brother Mr. Seymour Siegel - Father Park East Day School Mr. Leonard Brumberg - Mother Early Childhood Mrs. Ginette Reich - Mother Elementary School: Grades 1-5 Mr. Harvey Drucker - Father Middle School: Grades 6-8 Mr. Jack Shnay - Mother Ask about our incentive program! Mrs. Marjorie Schein - Father Mr. Andrew Feinman - Father Mommy & Me Mrs. Hermine Gewirtz - Sister Taste of School Mrs. Iris Lipke - Mother Tuesday and Thursday Mr. Meyer Stiskin - Father 9:00 am - 10:30 am or 10:45 am - 12:15 pm Ms. Judith Deich - Mother Mr. Joseph Guttmann - Father Providing children 14-23 months with a wonderful introduction to a more formal learning environment. Through Memorial Kaddish play, music, art, movement, and in memory of Shabbat and holiday programming, children learn to love school and Ethel Kleinman prepare to separate from their beloved mother of our devoted members February 7-8, 2020 u 12-13 Shevat, 5780 parents/caregivers. Elly (Shaindy) Kleinman, Leah Zeiger and Register online at ParkEastDaySchool.org Rabbi Yisroel Kleinman. Shabbat Shira - Tu B’Shevat or email [email protected] May the family be comforted among Musical Shabbat with Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Leon & Gina Fromer the mourners of Zion & Jerusalem. Youth Enrichment Center and Cantor Maestro Yossi Schwartz Hebrew School Parshat Beshalach Pre-K (Age 4) This Shabbat is known as Shabbat Shira Parshat Beshalach Kindergarten (Age 5) because the highlight of the Torah Reading Exodus 13:17-17:16 Haftarah Elementary School (Ages 6-12) is the Song at the Sea. -

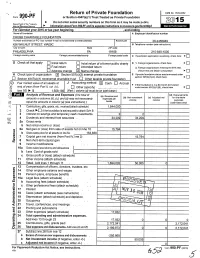

990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. M015 Department of the Treasury ► Internal R venue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990 For calendar year 2015 or tax year beg innin g and endin g Name of foundation A Employer identification number CHUBB C HARITABLE FOUNDATION Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 26-2456949 436 WALNUT STREET, WA09C B Telephone number (see instructions) City or town State ZIP code PHILADELPHIA PA 19106 215-640-1000 Foreign country name Foreign province/state/county Foreign postal code I q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► q q G Check all that apply, Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change Q Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under q section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► q Section 4947 (a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method © Cash q Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part fl, co/ (c), q Other (specify) under section 507(b)( 1)(B), check here ------------------------- ► '9 line 10; t . -

After Chabad: Enforcement in Cultural Property Disputes

Comment After Chabad: Enforcement in Cultural Property Disputes Giselle Barciat I. INTRODUCTION Cultural property is a unique form of property. It may be at once personal property and real property; it is non-fungible; it carries deep historical value; it educates; it is part tangible, part transient.' Cultural property is property that has acquired a special social status inextricably linked to a certain group's identity. Its value to the group is unconnected to how outsiders might assess its economic worth. 2 If, as Hegel posited, property is an extension of personhood, then cultural property, for some, is an extension of nationhood. Perhaps because of that unique status, specialized rules have developed, both domestically and internationally, to resolve some of the legal ambiguities inherent in "owning" cultural property. The United States, for example, has passed numerous laws protecting cultural property4 and has joined treaties and participated in international conventions affirming cultural property's special legal status.5 Those rules focus primarily on conflict prevention and rely upon t Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2013; University of Cambridge, M.Phil. 2009; Harvard University, A.B. 2008. Many thanks to Professor Amy Chua for her supervision, support, and insightful comments. I am also grateful to Camey VanSant and Leah Zamore for their meticulous editing. And, as always, thanks to Daniel Schuker. 1. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970 UNESCO Convention) defines cultural property as "property which, on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each State as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science." 1970 UNESCO Convention art. -

HERE's My STORY

ב״ה An inspiring story for your Shabbos table שבת פרשת צו, י״ג אדר ב׳, תשע״ד HERE’S Shabbos Parshas Tzav, March 15, 2014 my MY CAREER STORY IN THE MILITARY COLONEL JACOB GOLDSTEIN y parents are Holocaust survivors from Warsaw, where my father was educated in the Chabad Myeshiva , Tomchei Temimim. I was born right after the war, in 1946, in a displaced person’s camp where my parents were awaiting papers for America. When I was 11 years old, I came to study at the Chabad yeshiva in Crown Heights. I stayed there for many years, and this is where I eventually received my rabbinic ordination. In 1967, just before the Six Day War, the Rebbe began the first of his mitzvah campaigns to reach out to secular Jews. Some of the yeshiva students were designated to reach out to Jewish soldiers, to ask them to put on tefillin . We went to Camp Smith in Peekskill, where the New York Army National Guard is based. This was during the Vietnam War and a lot of Jewish boys joined the National In 1983, during the United States-led invasion of Guard because, even though you had to sign up for six Grenada, I was deployed there. On the fifth night of years, you wouldn’t get shipped out overseas. Chanukah, I was aboard a military plane when suddenly On that occasion, I first met the chaplain of the National the pilot motioned to me to put on the headset because Guard, Ed Donovan, a Roman Catholic priest, and from I had a call. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , ma r C h 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 275 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Property from the Library of a New England Scholar ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 21st March, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Maymyo” Sale Number Fifty Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y .