Rabbi Avraham Yizhak Hacohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness As a Religious Value

Source Sheet for Zvi Zohar’s presentation at Valley Beit Midrash Sephardic Halakha: Inclusiveness as a Religious Value Women Background: Chapter 31 of the Biblical book of Proverbs is a song of praise to the “Woman of Valor” (Eshet Hayyil). Inter alia, the Biblical author writes of the Eshet Hayyil: She is clothed in strength and glory, and smiles when contemplating the last day. She opens her mouth in wisdom, and instruction of grace is on her tongue… Her children rise up, and call her blessed; her husband praises her: 'Many daughters have done valiantly, but you are most excellent of them all.' Grace is deceitful, and beauty is vain; but a woman that feareth the LORD, she shall be praised. Give her of the fruits of her hands; and let her works praise her in the gates. Rabbi Israel Ya’akov AlGhazi (d. 1756) was born in Izmir and moved to Jerusalem, where he was subsequently chosen to be chief rabbi. His exposition of Eshet Hayyil is presented at length by his son, rabbi Yomtov AlGhazi, 1727-1802 (who was in his turn also chief rabbi of Jerusalem), in the homiletic work Yom Tov DeRabbanan, Jerusalem 1843. The following is a significant excerpt from that text: Text: And this is what is meant by the verse “She is clothed in strength and glory” – that she clothed herself in tefillin and tallit that are called1 “strength and glory”. And scripture also testifies about her, that she “smiles when contemplating the last day”, i.e., her reward on “the last day” – The World-To-Come – is assured. -

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug. 18 at 11:00 AM EDT Course Description: In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook delivered a fiery address criticizing the modern state of Israel for what he viewed as its founding sin: accepting the Partition Plan and dividing the Land of Israel. “Where is our Hebron?” he cried out. “Where is our Shechem, our Jericho… Have we the right to give up even one grain of the Land of God?” Just three weeks later, the Six Day War broke out, and the Israeli army conquered the biblical heartlands that Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda had mourned—in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. Hebron, Shechem, and Jericho were returned to Jewish sovereignty. In the aftermath of the war, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda’s words seemed almost prophetic. His spiritual vision laid the foundation for a new generation of religious Zionism and the modern settler movement, and his ideology continues to have profound implications for contemporary Israeli politics. In this session, we will explore Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook’s 1967 speech, his teachings, and his critics— particularly Rabbi Yehuda Amital. Guiding Questions: 1. How does Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook interpret the quotation from Psalm 107: "They have seen the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep"? Why do you think he begins this speech with this scripture? 2. In the section, "They Have Divided My Land," Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook tells two stories about responses to partition. Based on these stories, what do you think is his attitude toward diplomacy and politics is? 1 of 13 tikvahonlineacademy.org/ 3. -

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE of ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. in This

(No. 38) CHIEF RABBINATE OF ISRAEL LAW, 5740-1980* 1. In this Law -- "the Council " means the Council of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel; "town rabbi" means a person serving as a town rabbi after being elected under town rabbis' elections regulations made in pursuance of the Jewish Definitions. Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971(1), and a person serving as a town rabbi whose name is included in a list of town rabbis to be published by the Minister of Religious Affairs within sixty days from the date of the coming into force of this Law. 2. The functions of the Council are - (1) the giving of responsa and opinions on matters of halacha (religious law) to persons seeking its advice; (2) activities aimed at bringing the public closer to the values of tora (religious learning) and mitzvot (religious duties); (3) the issue of certificates of ritual fitness (kashrut) (hekhsher certificates); Functions of (4) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a dayan (judge of a religious Council. court) under the Dayanim Law, 5715-1955(2); (5) the conferment of eligibility to serve as a town rabbi under town rabbis' elections regulations made in persuance of the Jewish Religious Services Law (Consolidated Version), 5731-1971; (6) the conferment upon a rabbi of eligibility to serve as a rabbi and marriage registrar; (7) any act required for the carrying out of its functions under any law. Place of sitting of 3. The place of sitting of the Council shall be in Jerusalem. Council. 4. (a) The following are the members of the Council: o (1) the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, one a Sephardi, called Rishon Le- Zion, the other an Ashkenazi; they shall be elected in direct, secret and personal elections by an assembly of rabbis and representatives of Composition the public (hereinafter referred to as "the Electoral Assembly"); of Council. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Maran Harav Ovadia the Making of an Iconoclast, Tradition 40:2 (2007)

Israel’s Chief Rabbis II: Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu R’ Mordechai Torczyner - [email protected] A Brief Biography (continued) 1. Rabbi Yehuda Heimowitz, Maran Harav Ovadia At a reception for Harav Ovadia at the home of Israel’s president attended by the Cabinet and the leaders of the military, President Zalman Shazar and Prime Minister Golda Meir both urged the new Rishon LeZion to find some way for the Langer children to marry. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was particularly open about the government’s expectations, declaring, “I don’t care how you find a heter, the bottom line is that we have to rule leniently for those who were prevented from marrying.” By the time Harav Ovadia rose to address the crowd, the atmosphere in the room had grown tense, and it seemed at first that he would capitulate and guarantee to provide the solution they sought. His opening words were: “I am from a line of Rishon LeZions dating back more than 300 years,” he began, “all of whom worked with koha d’heteira to try to solve halachic issues that arose.” But before anyone could misinterpret his words, Harav Ovadia declared, “However, halacha is not determined at Dizengoff Square; it is determined in the beit midrash and by the Shulhan Aruch. If there is any way to be lenient and permit something, the Sephardic hachamim will be the first ones to rule leniently. But if there is no way to permit something, and after all the probing, investigating, and halachic examination that we do, we still cannot find a basis to allow it, we cannot permit something that is prohibited, Heaven forbid.”… On November 15, exactly one month after their election, Harav Ovadia felt that he had no choice but to report to the press that his Ashkenazi counterpart had issued an ultimatum four days earlier: If Harav Ovadia would not join him on a new three-man beit din, Chief Rabbi Goren would cut off all contact with him and refuse to participate in a joint inaugural ceremony. -

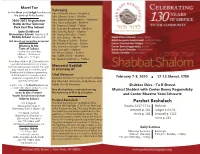

Parshat Beshalach

Mazel Tov Yahrzeits to the Dror and Sedgh families on Mrs. Marcelle Faust - Husband the birth of Mika Rachel. Mrs. Marion Gross - Mother 2020-2021 Registration Mrs. Batya Kahane Hyman - Husband Rabbi Arthur Schneier Mrs. Rose Lefkowitz - Brother Mr. Seymour Siegel - Father Park East Day School Mr. Leonard Brumberg - Mother Early Childhood Mrs. Ginette Reich - Mother Elementary School: Grades 1-5 Mr. Harvey Drucker - Father Middle School: Grades 6-8 Mr. Jack Shnay - Mother Ask about our incentive program! Mrs. Marjorie Schein - Father Mr. Andrew Feinman - Father Mommy & Me Mrs. Hermine Gewirtz - Sister Taste of School Mrs. Iris Lipke - Mother Tuesday and Thursday Mr. Meyer Stiskin - Father 9:00 am - 10:30 am or 10:45 am - 12:15 pm Ms. Judith Deich - Mother Mr. Joseph Guttmann - Father Providing children 14-23 months with a wonderful introduction to a more formal learning environment. Through Memorial Kaddish play, music, art, movement, and in memory of Shabbat and holiday programming, children learn to love school and Ethel Kleinman prepare to separate from their beloved mother of our devoted members February 7-8, 2020 u 12-13 Shevat, 5780 parents/caregivers. Elly (Shaindy) Kleinman, Leah Zeiger and Register online at ParkEastDaySchool.org Rabbi Yisroel Kleinman. Shabbat Shira - Tu B’Shevat or email [email protected] May the family be comforted among Musical Shabbat with Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Leon & Gina Fromer the mourners of Zion & Jerusalem. Youth Enrichment Center and Cantor Maestro Yossi Schwartz Hebrew School Parshat Beshalach Pre-K (Age 4) This Shabbat is known as Shabbat Shira Parshat Beshalach Kindergarten (Age 5) because the highlight of the Torah Reading Exodus 13:17-17:16 Haftarah Elementary School (Ages 6-12) is the Song at the Sea. -

Jewish Thought Journal of the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought

Jewish Thought Journal of the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought Editors Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Jonatan Meir Shalom Sadik Haim Kreisel (editor-in-chief) Editorial Secretary Asher Binyamin Volume 1 Faith and Heresy Beer-Sheva, 2019 Jewish Thought is published once a year by the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought. Each issue is devoted to a different topic. Topics of the following issues are as follows: 2020: Esotericism in Jewish Thought 2021: New Trends in the Research of Jewish Thought 2022: Asceticism in Judaism and the Abrahamic Religions Articles for the next issue should be submitted by September 30, 2019. Manuscripts for consideration should be sent, in Hebrew or English, as MS Word files, to: [email protected] The articles should be accompanied by an English abstract. The views and opinions expressed in the articles are those of the authors alone. The journal is open access: http://in.bgu.ac.il/en/humsos/goldstein-goren/Pages/Journal.aspx The Hebrew articles were edited by Dr. David Zori and Shifra Zori. The articles in English were edited by Dr. Julie Chajes. Address: The Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, PO Box 653, Beer-Sheva 8410501. © All Rights Reserved This issue is dedicated to Prof. Daniel J. Lasker for his 70Th birthday Table of Contents English Section Foreward 7 Michal Bar-Asher The Minim of the Babylonian Talmud 9 Siegal Menahem Kellner The Convert as the Most Jewish of Jews? 33 On the Centrality of Belief (the Opposite of Heresy) in Maimonidean Judaism Howard Kreisel Back to Maimonides’ Sources: 53 The Thirteen Principles Revisited George Y. -

Judaism and the Ethics of War

REVIEW Judaism and the ethics of war Norman Solomon* Norman Solomon served as rabbi to Orthodox congregations in Britain, and since 1983 has been engaged in interfaith relations and in academic work, most recently at the University of Oxford. He has published several books on Judaism. Abstract The article surveys Jewish sources relating to the justification and conduct of war, from the Bible and rabbinic interpretation to recent times, including special problems of the State of Israel. It concludes with the suggestion that there is convergence between contemporary Jewish teaching, modern human rights doctrine and international law. The sources and how to read them Judaism, like Christianity, has deep roots in the Hebrew scriptures ("Old Testament"), but it interprets those scriptures along lines classically formulated by the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud, completed shortly before the rise of Islam. The Talmud is a reference point rather than a definitive statement; Judaism has continued to develop right up to the present day. To get some idea of how Judaism handles the ethics of war, we will review a selection of sources from the earliest scriptures to rabbinic discussion in contemporary Israel, thus over a period of three thousand years. The starting point for rabbinic thinking about war is the biblical legisla- tion set out in Deuteronomy 20. In form this is a military oration, concerned with jus in bello rather than jus ad bellum; it regulates conduct in war, but does not specify conditions under which it is appropriate to engage in war. It distin- guishes between (a) the war directly mandated by God against the Canaanites * For a fuller examination of this subject with bibliography see Norman Solomon, "The ethics of war in the Jewish tradition", in The Ethics of War, Rochard Sorabji, David Robin et ah (eds.), Ashgate, Aldershot 2005. -

Finish As If He Were Polishing Steel"), Con- Rad

CURRENT BOOKS finish as if he were polishing steel"), Con- volt; the 1947 UN partition of Palestine rad Aiken (whose candor "evolved into a into Jewish and Arab states, the ensuing system of aesthetics and literary ethics civil war, and the creation of Israel in that unified his work"). John DOSPassos' 1948; the 1956 Suez Crisis; the 1967 Six- fictional trilogy U.S.A. (1930-36) was Day War; the 1973 Yom Kippur War. both a somber history of America during Sachar has added a brief epilogue carry- the first 30 years of this century and, by ing Israel's story from 1976 (when his means of such impressionistic devices as book was first published) to 1978. Here the "Camera Eye" passages, a reflection his treatment of Israeli domestic politics of the author's own feelings. Despite the is less detached. He interprets Prime Min- passing from fashion of young DOSPassos' ister Menachem Begin's May 1977 elec- radical views, U.S.A. "holds together," tion as a repudiation of the Labor gov- writes Cowley, "like a great ship freighted ernment's "flaccidity and corruption" with the dead and dying." after almost 30 years in power and blames the old Labor government's regu- HISTORY OF ISRAEL: From the Rise of latory zeal for Israel's declining economic Zionism to Our Time. By Howard M. growth. Sachar. Knopf, rev. ed., 1979. 954 pp. $9.95 THE SHOUT AND OTHER STORIES. By Robert Graves. Penguin reprint, 1979. The idea of a Jewish homeland had its 300 pp. $2.95 roots in early 19th-century European Jewish nationalism. -

Degel Rosh Hashanah 5774

שנה טובה RABBI DANIEL AND NA’AMAH ROSELAAR DEVORAH, ELISHEVA, NETANEL AND CHANANYA TOGETHER WITH KEHILLAT ALEI TZION שנה טובה WISH THE ENTIRE COMMUNITY A Anna-Leah and Raph Cooper Lauren, Simon and Tamar Levy Family Goldschneider Ayala, Ben and Efraim Savery Hannah, Yossi and Gilad Sarah, Nathan, Sophie and Hanstater Benjamin Woodward Stuart Izon CONTENTS Editor 4 Notes from the editor Elana Chesler ELANA CHESLER Editorial Team Judith Arkush 5 Voices of Awe: The Sound of the High Holy Days Simon Levy MIRIAM LEVENSON Design Simon Levy 9 Koren-Sacks Mahzorim – A Review RABBI DANIEL ROSELAAR Founding Editor Ben Elton 14 Can a Royal Decree be Revoked? Front cover illustration BEN FREEDMAN Yolanda Rosalki Yolanda Rosalki is an 22 Eschatology, Nationalism and Religious Zionism - Accelerating the End artist and illustrator. SIMON LEVY For more information on how her designs can enhance your simha, or 32 ‘A child born in Paris in 1933…’ Rav Aharon Lichtenstein at 80 – A Tribute if you wish to purchase RABBI JOE WOLFSON the original of the front cover artwork, email: [email protected] 37 Last Words YAEL UNTERMAN . Degel is a publication of the Alei Tzion Community. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the Rav, community or editors. | www.aleitzion.co.uk Schaller House, 44a Albert Road, London, NW4 2SJ | [email protected] 4 | NOTES FROM THE EDITOR Notes from the editor he High Holy Days present a range of formidable Given the close ties that Alei Tzion has with Yeshivat Har themes to stir our thoughts and challenge us. This Etzion (Gush) it was only appropriate that we include a year, with an “early” Yom Tov, the important tribute to Rav Lichtenstein, the Rosh Yeshiva, who T th preparation of the Ellul period might otherwise be celebrated his 80 birthday this year and we thank Rabbi undermined by the breezy mood of summer. -

Rabbi Benzion Meir Hai Uziel

Embracing Tradition and Modernity: Rabbi Benzion Meir Hai Uziel Byline: Rabbi Hayyim Angel Introduction One of the great rabbinic lights of the twentieth century was Rabbi Benzion Meir Hai Uziel (1880–1953). Born in Jerusalem, he served as Chief Rabbi of Tel-Aviv from 1911 to 1921, and then was Chief Rabbi of Salonika for two years. In 1923, he returned to Israel and assumed the post of Chief Rabbi of Tel-Aviv. From 1939 until his death in 1953, he was the Sephardic Chief Rabbi, the Rishon le-Tzion, of Israel. He served as Chief Rabbi during the founding of the State of Israel and wrote extensively on the halakhic ramifications of the State and the staggering changes in Jewish life it would bring. Rabbi Uziel believed that the purpose of the State of Israel on the world scene is to serve as a model nation, characterized by moral excellence. Just as individuals are religiously required to participate in the life of society, the Jewish people as a nation must participate in the life of the community of nations. Tanakh and rabbinic Judaism have a universalistic grand vision that sees Judaism as a great world religion. Unfortunately, too many religious Jews overemphasize the particularistic aspects of Judaism, and lose sight of the universalistic mission of the Torah. We cannot be a [1] light unto the nations unless nations see that light through Jewish involvement. Rabbi Uziel stressed the need for Jews to remain committed to Torah and the commandments. If Jews abandon their commitment to Torah, then they no longer are united under their national charter.