After Chabad: Enforcement in Cultural Property Disputes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chabad Chodesh Marcheshvan 5771

בס“ד MarCheshvan 5771/2010 SPECIAL DAYS IN MARCHESHVAN Volume 21, Issue 8 In MarCheshvan, the first Beis HaMikdash was completed, but was not dedicated until Tishrei of the following year. MarCheshvan was ashamed, and so HaShem promised that the dedication of the Third Beis HaMikdash would be during MarCheshvan. (Yalkut Shimoni, Melachim I, 184) Zechariah HaNavi prophesied about the rebuilding of the Second Beis HaMikdash. Tishrei 30/October 8/Friday First Day Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan MarCheshvan 1/October 9/Shabbos Day 2 Rosh Chodesh MarCheshvan father-in-law of the previous Lubavitcher Shlomoh HaMelech finished building the Rebbe, 5698[1937]. Beis HaMikdash, 2936 [Melachim I, 6:35] Cheshvan 3/October 11/Monday Cheshvan 2/October 10/Sunday Yartzeit of R. Yisroel of Rizhyn, 5611[1850]. The Rebbe RaShaB sent a Mashpiah and "...The day of the passing of the Rizhyner, seven Talmidim to start Yeshivah Toras Cheshvan 3, 5611, was very rainy. At three in Emes, in Chevron, 5672 [1911]. the afternoon in Lubavitchn, the Tzemach Tzedek called his servant to tear Kryiah for Yartzeit of R. Yosef Engel, Talmudist, 5679 him and told him to bring him his Tefilin. At [1918]. that time news by telegraph didn't exist. The Rebbitzen asked him what happened; he said Yartzeit of R. Avrohom, son of R. Yisroel the Rizhyner had passed away, and he Noach, grandson of the Tzemach Tzedek, LUCKY BRIDES - TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCKI NPARK HONOR OF THE BIRTHDAY OF THE REBBE RASHAB The fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom ular afternoon he remained in that position for DovBer, used to make frequent trips abroad a much longer time than usual. -

Days in Chabad

M arC heshvan of the First World War, and as a consequence, the Hirkish authorities decided to expel all Russian nationals living in Eretz Yisrael. Thus, teacher and students alike were obli gated to abandon Chevron and malte the arduous journey back to Russia. Tohioi Chabad b'Eretz Hakodesh Passing of Rabbi Avraham Schneersohn, 2 Mar- FATHER-IN-LAW OF THE ReBBE, R, YOSEF YiTZCHAK Cheshvan 5 6 9 8 /1 9 3 7 Rabbi Avraham Schneersohn was bom in Lubavitch, in S ivan 5620 (1860). His father was Rabbi Yisrael Noach, son of the Tzemach Tkedek ; his mother, Rebbetzin Freida, daughter of Rebbetzin Baila, who was the daughter of the Mitteler Rebbe. In the year 5635 (1875), he married Rebbetzin Yocheved, daughter of Rabbi Yehoshua Fallilc Sheinberg, one of the leading chasidim in the city of Kishinev. After his marriage, he made his home in !Kishinev and dedicat ed himself to the study of Torah and the service of G-d. Rabbi Avraham was well-known for his righteousness, his piety and his exceptional humility. When his father passed away, his chasidim were most anxious for Rabbi Avraham to take his place, but he declined to do so and remained in Kishinev. In order to support himself he went into business, even then devoting the rest of his life to the study of Torah and the service of G-d. He was interred in Kishinev. Hakriah v’Hakedusha Passing of Rabbi Yehuda Leib, the “M aharil” 3 Mar- OF KoPUST, son of THE TZEMACH TZEDEK Cheshvan 5 6 2 7 /1 8 6 6 Rabbi Yehuda Leib, known as the “Maharil,” was bom in 5568 (1808). -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held May 2Nd, 2013

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts & autograph Letters including hoLy Land traveL the ColleCtion oF nathan Lewin, esq. K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m ay 2nd, 2013 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 318 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, & AUTOGRAPH LETTERS INCLUDING HOLY L AND TR AVEL THE COllECTION OF NATHAN LEWIN, ESQ. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, May 2nd, 2013 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, April 28th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, April 29th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, April 30th - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, May 1st - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Pisgah” Sale Number Fifty-Eight Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. (Consultant) Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

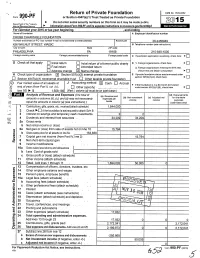

990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. M015 Department of the Treasury ► Internal R venue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990 For calendar year 2015 or tax year beg innin g and endin g Name of foundation A Employer identification number CHUBB C HARITABLE FOUNDATION Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 26-2456949 436 WALNUT STREET, WA09C B Telephone number (see instructions) City or town State ZIP code PHILADELPHIA PA 19106 215-640-1000 Foreign country name Foreign province/state/county Foreign postal code I q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► q q G Check all that apply, Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change Q Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under q section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► q Section 4947 (a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method © Cash q Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part fl, co/ (c), q Other (specify) under section 507(b)( 1)(B), check here ------------------------- ► '9 line 10; t . -

The Corona Ushpizin

אושפיזי קורונה THE CORONA USHPIZIN Rabbi Jonathan Schwartz PsyD Congregation Adath Israel of the JEC Elizabeth/Hillside, NJ סוכות תשפא Corona Ushpizin Rabbi Dr Jonathan Schwartz 12 Tishrei 5781 September 30, 2020 משה תקן להם לישראל שיהו שואלים ודורשים בענינו של יום הלכות פסח בפסח הלכות עצרת בעצרת הלכות חג בחג Dear Friends: The Talmud (Megillah 32b) notes that Moshe Rabbeinu established a learning schedule that included both Halachic and Aggadic lessons for each holiday on the holiday itself. Indeed, it is not only the experience of the ceremonies of the Chag that make them exciting. Rather, when we analyze, consider and discuss why we do what we do when we do it, we become more aware of the purposes of the Mitzvos and the holiday and become closer to Hashem in the process. In the days of old, the public shiurim of Yom Tov were a major part of the celebration. The give and take the part of the day for Hashem, it set a tone – חצי לה' enhanced not only the part of the day identified as the half of the day set aside for celebration in eating and enjoyment of a חצי לכם for the other half, the different nature. Meals could be enjoyed where conversation would surround “what the Rabbi spoke about” and expansion on those ideas would be shared and discussed with everyone present, each at his or her own level. Unfortunately, with the difficulties presented by the current COVID-19 pandemic, many might not be able to make it to Shul, many Rabbis might not be able to present the same Derashos and Shiurim to all the different minyanim under their auspices. -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , ma r C h 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 275 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Property from the Library of a New England Scholar ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 21st March, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Maymyo” Sale Number Fifty Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . -

Fine Judaica

t K ESTENBAUM FINE JUDAICA . & C PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, GRAPHIC & CEREMONIAL ART OMPANY F INE J UDAICA : P RINTED B OOKS , M ANUSCRIPTS , G RAPHIC & C & EREMONIAL A RT • T HURSDAY , N OVEMBER 12 TH , 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY THURSDAY, NOV EMBER 12TH 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 115 Catalogue of FINE JUDAICA . Printed Books, Manuscripts, Graphic & Ceremonial Art Featuring Distinguished Chassidic & Rabbinic Autograph Letters ❧ Significant Americana from the Collection of a Gentleman, including Colonial-era Manuscripts ❧ To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 12th November, 2020 at 1:00 pm precisely This auction will be conducted only via online bidding through Bidspirit or Live Auctioneers, and by pre-arranged telephone or absentee bids. See our website to register (mandatory). Exhibition is by Appointment ONLY. This Sale may be referred to as: “Shinov” Sale Number Ninety-One . KESTENBAUM & COMPANY The Brooklyn Navy Yard Building 77, Suite 1108 141 Flushing Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11205 Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Zushye L.J. Kestenbaum Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Judaica & Hebraica: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Shimon Steinmetz (consultant) Fine Musical Instruments (Specialist): David Bonsey Israel Office: Massye H. Kestenbaum ❧ Order of Sale Manuscripts: Lot 1-17 Autograph Letters: Lot 18 - 112 American-Judaica: Lot 113 - 143 Printed Books: Lot 144 - 194 Graphic Art: Lot 195-210 Ceremonial Objects: Lot 211 - End of Sale Front Cover Illustration: See Lot 96 Back Cover Illustration: See Lot 4 List of prices realized will be posted on our website following the sale www.kestenbaum.net — M ANUSCRIPTS — 1 (BIBLE). -

Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published Online: 09 Sep 2014

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania] On: 11 September 2014, At: 10:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Media and Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjmr20 Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published online: 09 Sep 2014. To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2014) Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad-Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere, Journal of Media and Religion, 13:3, 123-137 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2014.938973 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

United States Court of Appeals

USCA Case #07-7002 Document #1121539 Filed: 06/13/2008 Page 1 of 39 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued March 17, 2008 Decided June 13, 2008 No. 07-7002 AGUDAS CHASIDEI CHABAD OF UNITED STATES, APPELLEE/CROSS-APPELLANT v. RUSSIAN FEDERATION, RUSSIAN MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND MASS COMMUNICATION, RUSSIAN STATE LIBRARY, AND RUSSIAN STATE MILITARY ARCHIVE, APPELLANTS/CROSS-APPELLEES Consolidated with 07-7006 Appeals from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (No. 05cv01548) James H. Broderick, Jr. argued the cause for appellants/cross-appellees. With him on the briefs was Donald T. Bucklin. Nathan Lewin argued the cause for appellee/cross- appellant. With him on the briefs were Marshall B. USCA Case #07-7002 Document #1121539 Filed: 06/13/2008 Page 2 of 39 2 Grossman, Seth M. Gerber, Alyza D. Lewin, and William B. Reynolds. Before: HENDERSON, Circuit Judge, and EDWARDS and WILLIAMS, Senior Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Senior Circuit Judge WILLIAMS. Opinion concurring in the judgment filed by Circuit Judge HENDERSON. WILLIAMS, Senior Circuit Judge: Agudas Chasidei Chabad of United States is a non-profit Jewish organization incorporated in New York. It serves as the policy-making and umbrella organization for Chabad-Lubavitch—generally known as “Chabad”—a worldwide Chasidic spiritual movement, philosophy, and organization founded in Russia in the late 18th century. (Chabad’s name is a Hebrew acronym standing for three kinds of intellectual faculties: Chachmah, Binah, and Da’at, meaning wisdom, comprehension, and knowledge.) In every generation since the organization’s founding, it has been led by a Rebbe—a rabbi recognized by the community for exceptional spiritual qualities. -

The Chabad Times

Happy Purim! Non Profit Org. U.S. postage PAID Rochester, NY Permit No. 4237 CHABAD LUBAVITCH ROCHESTER NY THE CHABAD TIMES A Publication of Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester Kessler Family Chabad Center Chabad Of Pittsford Chabad Young Professionals Rohr Chabad House @ U of R Chabad House @ R.I.T. 1037 Winton Rd. S. 21 Lincoln Ave. 18 Buckingham St. 955 Genesee St. 91 York Bay Trail Rochester NY 14618 Pittsford, NY 14534 Rochester, NY 14607 Rochester, NY 14611 West Henrietta NY 14586 585-271-0330 585-385-2097 585-350-6634 585-503-9224 347-546-3860 ww.chabadrochester.com www.jewishpittsford.com www.yjparkave.com www.urchabad.org www.chabadrit.com VOLUME 38 NUMBER 2 ADAR 5781 V”C MARCH 2021 www.chabadrochester.com/purim page 2 The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Adar 5781 and never get sick of it" is one of those innocuous phrases that upwardly mobile people with enough petty cash to regularly eat the stuff seem to repeatedly declare as they dig into their sixth or seventh piece. I bet they would eat those very words after, say, their twenty-sec- ond piece on the third day of the nothing-but-sushi diet. If one were actually crazy enough to voluntarily con- sume the same meal for the The Final Word rest of their life, my own per- by Yerachmiel Tilles sonal field research has lead me to believe that there is It was with heavy hearts that a group of senior chas- nothing more fitting for the sidim assembled in the home of their rebbe, Rabbi Zvi- Hell's Kitchen by Matt Brandstein task than the Kosher Delight Elimelech of Dinov, the "Bnei Yissaschar". -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, Ceremonial obJeCts & GraphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, nov ember 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 61 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, GR APHIC & CEREMONIAL A RT INCLUDING A SINGULAR COLLECTION OF EARLY PRINTED HEBREW BOOK S, BIBLICAL & R AbbINIC M ANUSCRIPTS (PART II) Sold by order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th November, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th November - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 16th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Sempo” Sale Number Sixty Six Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky (Consultant) Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H.