Taking Stock, Placing Orders: a Historiographic Essay on the Business History of the Newspaper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Blogization of Journalism

DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of School of Communication, Media and Theatre of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Lecture Room Linna K 103, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on May 17th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Communication, Media and Theatre Finland Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1418 ISBN 978-951-44-9450-5 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9451-2 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Preface I owe many thanks to you who made this work possible. I am grateful to you for making it worthwhile. It is hard to name you all, or rather it is impossible. By reading this, you certainly belong to those to whom I radiate my gratitude. Thank you all for your attention and critique, for a friendly talk and timely empathy. My special thanks to my teachers. To Ruslan Bekurov, my master’s thesis advisor at the university in Saint-Petersburg, who encouraged me to pursue the doctoral degree abroad. To Kaarle Nordenstreng, my local “fixer” and a brilliant mentor, who helped me with my first steps at the University of Tampere. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

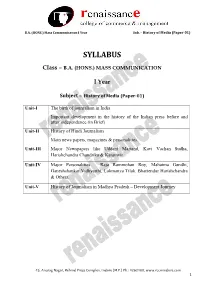

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

JOU4004 HISTORY of JOURNALISM Fall 2020 | Class 15287, Section 2677 | Online 100% | 3 Credits

JOU4004 HISTORY OF JOURNALISM Fall 2020 | Class 15287, Section 2677 | Online 100% | 3 credits Dr. Bernell E. Tripp Office: 3055 Weimer Hall Office hours: Wednesdays 2:00 to 5:00 pm / All other available times by appointment. Office Phone: 352-392-2147 E-mail: [email protected] COURSE PURPOSE: To understand the media’s continued relevancy in the lives of its audience, it is much more important to remember – and see connections among – trends and significant social movements, and to connect those trends and movements to our modern lives. Students will be introduced to major issues and themes in the history of journalism in America. This thematic approach allows students to trace the major changes in the practice of journalism and mass communications and to understand the key instances in which the practice of journalism brought change to America in the larger societal, economic, cultural, and political spheres. COURSE STRUCTURE: This course is a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous learning tools through Canvas. Instructor lectures and guest speaker presentations will be a synchronous hybrid of Zoom meetings and/or prerecorded videos on class meeting days at the scheduled times (Tuesdays, 11:45 a.m.-1:40 p.m.; Thursdays, 12:50-1:40 p.m.). Synchronous online lectures will vary from one hour to 75 minutes, depending on the topic or the speaker. If possible, Thursdays will the designated day for asynchronous materials such as required supplemental videos, podcasts, PowerPoint presentations, etc., as well as assignment submissions for the research paper/project. Quizzes on weekly lectures, textbook readings, and supplemental materials will also be tentatively scheduled for completion by Saturdays by 11:59 p.m., unless there is a conflict on the calendar. -

JOUR 201: History of News in Modern America 4 Units Spring 2016 – Mondays & Wednesdays 3:30-4:50Pm Section: 21008D Location: ANN-L105A

JOUR 201: History of News in Modern America 4 Units Spring 2016 – Mondays & Wednesdays 3:30-4:50pm Section: 21008D Location: ANN-L105A Instructor: Mike Ananny, PhD Office: ANN-310B Office Hours: Mondays & Wednesdays 1:45-2:45pm Contact Info: [email protected] Teaching Assistant: Emma Daniels Office: ANN lobby Office Hours: Mondays 5-6pm Contact Info: [email protected] I. Course Description The goal of this course is to introduce students to key moments, debates, and ideas that have shaped U.S. journalism from about the Revolutionary War period through today. Since this is a survey class, we won’t be spending too much time on any one topic, time period, or analytical framework. Instead, each class will examine social, cultural, political, and technological aspects of U.S. journalism, getting a sense of its overarching history as a profession and public service. E.g., how has the press historically both depended upon and challenged the state? How has the press funded itself? Where did the idea of journalistic objectivity come from and what does it mean? How has news served both market and public interests? What legal decisions shape the press’s rights and responsibilities? How does the press organize itself, and reorganize itself in light of technological innovation? At several points in the course, world-class scholars and practitioners will give guest lectures, sharing with us their experiences studying and working within the U.S. press. We’ll hear first-hand accounts of what it’s been like to participate in different periods of modern American journalism, examine historical archives of press coverage, and will end the semester with a review of how today’s journalism is tied to historical patterns. -

The History of Mexican Journalism

THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI BULLETIN VOLUME 29, NUMBER 4 JOURNALISM SERIES, NO. 49 Edited by Robert S. Mann The History of Mexican Journalism BY HENRY LEPIDUS ISSUED FOUR TIMES MONTHLY; ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER AT THE POSTOFFICE AT COLUMBIA, MISSOURl-2,500 JANUARY 21, 1928 2 UNIVERSfTY oF Mrssouru BULLETIN Contents I. Introduction of Printing into Mexico and the Forerunners of Journalism ______ 5 II. Colonial Journalism -------------------------------------------------------12 III. Revolutionary Journalism --------------------------------------------------25 IV. From Iturbide to Maximilian -----------------------------------------------34 V. From the Second Empire to "El lmparcial" --------------------------------47 VI. The Modern Period -------------------------------------------------------64 Conclusion ---------------------------___________________________________________ 81 Bibliography --------__ -------------__________ -----______________________________ 83 THE HISTORY OF MEXICAN JOURNALISM 3 Preface No continuous history of Mexican journalism from the earliest times to the present has ever been written. Much information on the subject exists, but nobody, so far as I know, has taken the trouble to assemble the material and present it as a whole. To do this within the limits necessarily imposed upon me in the present study is my principal object. The subject of Mexican journalism is one concerning which little has been written in the United States, but that fact need not seem su;prising. With compara tively few exceptions, Americans of international interests have busied themselves with studies of European or even Oriental themes; they have had l;ttle time for. the study of the nations south of the Rio Grande. More recently, however, the im portance of the Latin American republics, particularly Mexico, to us, has been in creasingly recognized, and the necessity of obtaining a clearer understanding of our southern neighbor has come to be more widely appreciated in the United States than it formerly was. -

Evolution of Journalism and Mass Communication - Kathleen L

JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION – Vol. I - Evolution of Journalism and Mass Communication - Kathleen L. Endres EVOLUTION OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Kathleen L. Endres The University of Akron, Ohio, USA Keywords: Journalism, Mass Communication, Newspapers, Magazines, Radio, Television, Internet, Printing, Broadcasting, Photography, Telegraph, Censorship Contents 1. Introduction 2. Themes Affecting Journalism and Mass Communication 3. Technology Brings Changes to Journalism and Mass Communication 3.1. Earliest History 3.2. Earliest News Sheets 3.3. Technological Advances in Printing—Part I—and Paper-Making Production 3.4. Decline of Journalism in the West 3.5. Technological Advances in Printing—Part II 3.6. Technological Revolution of the Nineteenth Century 3.7. Radio 3.8. Television 3.9. Internet 4. Concentration of Ownership 4.1. Earliest History 4.2. Corporatization of Publishing 4.3. Broadcasting Ownership Trends 4.4. Global Media Ownership Trends 4.5. Internet and Decentralization of Ownership/Control 5. Audience Segmentation 5.1. Audience of Early Journalism 5.2. Publishing and Broadcasting for the Masses 5.3. Segmentation of the Audience 6. Changes in the Journalism Workforce 6.1. Early Trends 6.2. Improved Education 6.3. Moves Toward Diversifying the Journalism Workplace 7. TheUNESCO Future of Journalism and Mass Communication– EOLSS Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Journalism dates back many centuries, to a time before modern forms of mass communication. This essay looks at the evolution of journalism and mass communication worldwide, from its earliest days to today. The chapter looks at five major trends in that evolution. The first trend is technological. Over the centuries, technical innovations and inventions have brought increased speed of production and ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION – Vol. -

Why Do Journalists Fact-Check? the Role of Demand- and Supply-Side Factors

Why do journalists fact-check? The role of demand- and supply-side factors Lucas Graves Brendan Nyhan University of Wisconsin Dartmouth College [email protected] [email protected] Jason Reifler University of Exeter j.reifl[email protected] January 14, 2016 Abstract Why has fact-checking spread so quickly within U.S. political journalism? The practice does not appear to diffuse organically at a state or regional level — PolitiFact affiliates had no effect on fact-checking coverage by other news- papers in their states during 2012. However, results from a field experiment in 2014 show that messages promoting the high status and journalistic values of fact-checking increased the prevalence of fact-checking coverage, while messages about audience demand were somewhat less successful. These findings suggest that the spread of fact-checking is driven primarily by pro- fessional motives within journalism. We thank Democracy Fund and the American Press Institute for generous funding support. We also thank Kevin Arceneaux, Toby Bolsen, Andrew Hall, Shawnika Hull, Joshua Kertzer, Jacob Mont- gomery, Costas Panagopoulos, Ethan Porter, Hernando Rojas, Edward Walker, and participants in the Experimental Studies of Elite Behavior conference at Yale University for helpful comments. We are indebted to Alex Carr, Megan Chua, Caitlin Cieslik-Miskimen, Sasha Dudding, Lily Gordon, Claire Groden, Miranda Houchins, Thomas Jaime, Susanna Kalaris, Lindsay Keare, Taylor Malmsheimer, Lauren Martin, Megan Ong, Ramtin Rahmani, Rebecca Rodriguez, Mark Sheridan, Marina Shkura- tov, Caroline Sohr, Heather Szilagyi, Mackinley Tan, Mariel Wallace, and Marissa Wizig for excel- lent research assistance. The conclusions and any errors are, of course, our own. -

A History of Journalism

A History of Journalism Objectives After reading this section, you will be able to: · Discuss the interplay between technologies and the development of journalism. · List the four roles of mass media. · Discuss the development of a free press. · Discuss methods used to pay for the collection and dissemination of news. · Identify ethical challenges that may develop because of sources of funding. · Identify strengths and weaknesses associated with media convergence. Humans hunger for news. We want knowledge beyond what we can gather using our own senses. We want narratives, facts, events, people, back stories and the ideas from beyond our doors. We want to understand, and we want to escape our isolation. The mass media tries to satisfy this hunger. The work journalists produce is part of mass media. Mass media’s job is to inform, persuade, entertain and transmit cultural values. Journalism openly and proudly does the first three—it persuades, informs and entertains—and often, despite its efforts to be objective, it reflects and transmits cultural values. Sometimes these roles of mass media conflict with each other. “The Odyssey,” one of the oldest works in Western literature, is full of the hunger for news. Twenty years after Odysseus sails for Troy, his wife and son long for news of him. But in Greece in 800 BCE, there are only two ways of getting news. You can stay at home and hope a traveler comes to you with accurate reports, or you can travel forth to interview primary sources for yourself. Literacy had not yet reached Greece. The story of Odysseus represents the four sometimes competition functions of mass communication: to inform, persuade, entertain and transmit culture. -

Sharing the News: Journalistic Collaboration As Field Repair

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 1966–1984 1932–8036/20150005 Sharing the News: Journalistic Collaboration as Field Repair LUCAS GRAVES1 University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA MAGDA KONIECZNA Temple University, USA Organized journalism in every era offers examples of news sharing: cooperative practices by which rival news outlets work together to produce or distribute news. Today, this behavior is being institutionalized by certain emergent news organizations. To understand news sharing, we argue, requires attention to how these journalists seek to not only practice but repair the field of journalism. This article analyzes news sharing as a form of field repair, drawing on ethnographic studies of investigative news nonprofits and professional fact-checking groups. We argue that journalism’s “high- modern” era, with its broad alignment of economic and professional goals, highlighted competitive rather than collaborative elements of newswork. As that alignment unravels, journalists are engaging in explicit news sharing in pursuit of two intertwined goals: to increase the impact of their own reporting and to build institutional resources for public- affairs journalism to be practiced more widely across the field. Keywords: public affairs journalism, news nonprofits, fact-checking, collaboration Introduction Journalism is usually seen as a competitive occupation, defined by the rivalry among individual reporters and among news organizations. This is not without reason. Journalists guard their sources and stories jealously, sometimes even from peers in the same newsroom. Covering a story first or best brings professional rewards, while being beaten by a rival is a badge of shame for reporter and news outlet alike. Most important, almost all news organizations—even noncommercial ones—depend for their survival on attracting loyal audiences. -

Quality in Journalism: Perceptions and Practice in an Indian Context

Quality in Journalism: Perceptions and Practice in an Indian context By: Sreedevi Purayannur A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Journalism Studies Submission Date March 2018 To Amma My guru and my friend 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is often said that undertaking a PhD is a solitary journey. I have been fortunate to enjoy enormous support and the encouragement of many well-wishers at all stages of this journey. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Martin Conboy, whose continuous support, encouragement and enthusiasm for my work led me to the completion of this thesis. I am grateful for his guidance, knowledge and constructive feedback towards my training as a researcher over the years. I would also like to thank Professor John Steel for his feedback on my MPhil to PhD upgrade report and on the first complete draft of this thesis. On both occasions, his comments forced me to challenge the contours of my study, and this thesis is all the better for them. At the Department of Journalism Studies, I would like to thank Clare Burke and Jose Cree for their administrative support; Ximena Orchard for her help in many instances during our time together at Sheffield; and Professor Jackie Harrison for for opening the doors for this PhD in the first instance. I am very grateful to all the journalists who found the time in their busy schedules to share their experiences. Their contribution made this thesis meaningful. -

JOURNALISM and MASS COMMUNICATION – Vol

JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION – Vol. I - History and Development of Mass Communications - LaurieThomas Lee HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATIONS LaurieThomas Lee Department of Broadcasting, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA Keywords: audion, CATV, circulation, convergence, DBS, dime novels, domsat, FM, formats, Gutenberg, Internet, linotype, Marconi, muckraking, papyrus, penny press, press association, satellite, yellow journalism Contents 1. Introduction 2. Books 2.1. The Printing Press 2.2.Competition and Consolidation 3. Newspapers 3.1. Control and Demand 3.2. Developing Content 3.3. Competition and Consolidation 4. Magazines 4.1. Industry Growth 4.2. Competition and Specialization 5. Radio 5.1. Early Operations 5.2. Industry Growth 5.3. Competition and Change 6. Television 6.1. Programming 6.2. Issues 7. Newer Media 7.1. Cable Television 7.2. Satellite Television 7.3. Wireless Cable 7.4. The Internet 8. ConclusionsUNESCO – EOLSS Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch SAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary Mass communications history is fairly short, although the various forms of mass media that have developed over the years have made a tremendous impression on the technological, political, economic, social and cultural trends of every nation. Mass communications, defined as communication reaching large numbers of people, primarily developed in just the last 500 years. Earlier developments, along with technological advances and social change, helped spark the demand and innovation necessary for creating today's mass media. ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION – Vol. I - History and Development of Mass Communications - LaurieThomas Lee Books are the oldest of the media, with the first known book written in Egypt around 1400 B.C.