The Blogization of Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Opinion, Journalism and the Question Offinland's Membership Of

10.1515/nor-2017-0211 Nordicom Review 28 (2007) 2, pp. 81-92 Public Opinion, Journalism and the Question of Finland’s Membership of NATO JUHO RAHKONEN Abstract The big question behind the research on media and democracy is: do media influence public opinion and the actual policy? The discussion about Finland’s NATO membership is a case in point. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, there has been a continuous public debate about whether Finland should join NATO. In the last 16 years, however, public opinion on NATO membership has not changed much. Despite the changes in world politics, such as NATO enlargement and new weapons technology, Finns still rely on military non-alliance and want to keep their own army strong. During the last ten years, there seems to be no correlation between media coverage and public opinion: pro-NATO media content has not been able to make Finns’ attitudes towards NATO more positive. The information provided by most of the Finnish newspapers is different from the way ordinary people see NATO. In the papers’ view, joining the alli- ance would be a natural step in Finland’s integration into Western democratic organiza- tions. Ordinary people on the contrary consider NATO more as a (U.S. led) military alli- ance which is not something Finland should be a part of. Historical experiences also dis- courage military alignment. In the light of data drawn from newspaper articles and opin- ion polls, the article suggests that journalism has had only a slight effect on public opin- ion about Finland’s NATO membership. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

The Oregonian Editorial Board and Sam Adams Teaching Note

CSJ‐ 09 ‐ 0023.3 A Matter of Opinion: The Oregonian Editorial Board and Sam Adams Teaching Note Case Summary Ever since the 1850s, when New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley established a distinct page for opinion, most newspapers have—at least officially—separated factual reporting from personal views. As a result, the right to voice opinions has been confined to a relative minority— notably columnists, guest essayists, and editorial writers. But while columns and guest pieces are typically authored by individuals who present personal ideas under their own bylines, editorials are produced by a group of people who anonymously articulate the position of the paper itself. This case focuses on the editor of one such group at the Oregonian newspaper in 2009 as he and his colleagues struggled to respond to a local scandal. In January, news broke that Portland’s openly‐gay and popular new mayor, Sam Adams, had been romantically involved with a man who may have been a minor at the time. The information challenged the Oregonian’s seven‐person editorial board, which had endorsed Adams just eight months earlier and was now faced with a quandary: Should it call for his resignation? Complicating their decision was the fact that Adams had categorically denied the two‐year‐old affair when a rival mayoral candidate raised the rumor eight months earlier. Students follow the Oregonian as it weighs how to respond to the evolving scandal. They trace the history of the paper’s editorial board, and learn about its ideological composition, as well as its staffing structure. They also learn about Oregon’s politics, the state’s previous political sex scandals, Adams’ political rise, and rumors of his alleged sexual relationship with a minor. -

Homosexuality in the USSR (1956–82)

Homosexuality in the USSR (1956–82) Rustam Alexander Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 School of Historical and Philosophical Studies Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Abstract The history of Soviet homosexuality is largely unexplored territory. This has led some of the few scholars who have examined this topic to claim that, in the period from Stalin through to the Gorbachev era, the issue of homosexuality was surrounded by silence. Such is the received view and in this thesis, I set out to challenge it. My investigation of a range of archival sources, including reports from the Soviet Interior Ministry (MVD), as well as juridical, medical and sex education literature, demonstrates that although homosexuality was not widely discussed in the broader public sphere, there was still lively discussion of it in these specialist and in some cases classified texts, from 1956 onwards. The participants of these discussions sought to define homosexuality, explain it, and establish their own methods of eradicating it. In important ways, this handling of the issue of homosexuality was specific to the Soviet context. This thesis sets out to broaden our understanding of the history of official discourses on homosexuality in the late Soviet period. This history is also examined in the context of and in comparison to developments on this front in the West, on the one hand, and Eastern Europe, on the other. The thesis draws on the observation made by Dan Healey, the pioneering scholar of Russian and Soviet sexuality, that in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death a combination of science and police methods was used to strengthen heterosexual norms in the Soviet society. -

Analisis Y Diagnostico De La Seguridad Informatica De Indeportes Boyaca

ANALISIS Y DIAGNOSTICO DE LA SEGURIDAD INFORMATICA DE INDEPORTES BOYACA ANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ CARRILLO 53070244 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL ABIERTA Y A DISTANCIA “UNAD” ESPECIALIZACION EN SEGURIDAD INFORMATICA TUNJA 2014 ANALISIS Y DIAGNOSTICO DE LA SEGURIDAD INFORMATICA DE INDEPORTES BOYACA ANA MARIA RODRIGUEZ CARRILLO 53070244 Trabajo de grado como requisito para optar el título de Especialista En Seguridad informática Ingeniero SERGIO CONTRERAS Director de Proyecto UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL ABIERTA Y A DISTANCIA UNAD ESPECIALIZACION EN SEGURIDAD INFORMATICA TUNJA 2014 _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Firma del presidente del jurado _____________________________________ Firma del jurado _____________________________________ Firma del jurado Tunja, 06 de Octubre de 2014. DEDICATORIA El presente trabajo es dedicado en primera instancia a Dios quien día a día bendice mi profesión y me ayuda con cada uno de los retos que se me presentan a lo largo del camino de mi vida. A mi fiel compañero, amigo, cómplice y esposo, quien es la ayuda idónea diaria y mi fortaleza constante para seguir en el camino del conocimiento, quien no deja que me rinda y me apoya incondicionalmente para que día a día logre ser mejor persona. A mis familiares y compañeros de trabajo, por todo su amor, confianza y apoyo incondicional, a nuestros compañeros y profesores gracias por la amistad, la comprensión, los conocimientos y dedicación a lo largo de todo este camino recorrido que empieza a dar indudablemente los primeros frutos que celebramos. AGRADECIMIENTOS La vida está llena de metas y retos, que por lo general van de la mano con grandes sacrificios, por eso hoy podemos decir que gracias a Dios y nuestras familias esta meta se ha cumplido y seguramente vendrá muchas metas que harán parte de nuestro gran triunfo personal como familiar. -

Twitter Taken Down by Ddos Attack August 2009

the Availability Digest www.availabilitydigest.com Twitter Taken Down by DDoS Attack August 2009 On Thursday, August 6, 2009, the Twitter social networking site went down. It suffered repeated outages, timeouts, and serious slowdowns for at least two days. What caused this failure? To add to the mystery, Facebook and LiveJournal simultaneously had similar problems. Were these outages somehow related? They occurred at about the same time as the 2009 Defcon 17 hackers conference held from July 30th to August 2nd. Could this have been some misguided mischief? But first, what is Twitter? For those who haven’t yet become addicted, Twitter is a microblogging social networking site that allows users to communicate what they are doing to their “followers” at any time via 140-character text messages, or “tweets.” Twitter was born in 2006 and has exploded in use. It currently has about five-million registered users, and an estimated 45 million people follow these users via their tweets. Twitter sprung into the mainstream when Republican presidential candidate John McCain joined the 21st century technology by embracing tweeting following the 2008 U.S. presidential election. Even more recently, and perhaps more importantly, Twitter was the primary communication mechanism to the rest of the world from those Iranians participating in the major rallies decrying the recent Iranian presidential election process. The untimely death of Michael Jackson also saw a massive increase in tweet volume. The Twitter Outage Access to Twitter Lost Twitter has not been known for its availability record. Pingdom, a web-site monitoring service,1 reports that Twitter was down for 84 hours in 2008, achieving only a 99% uptime.2 It should be noted, however, that Twitter is working hard to improve this record; and its uptime improved significantly in the second half of 2008. -

E Helsinki Forum and East-West Scientific Exchange

[E HELSINKI FORUM AND EAST-WEST SCIENTIFIC EXCHANGE JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND THE Sul COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL SECURITY AND SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE NINETY-SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 31, 1980 [No. 89] (Committee on Science and Technology) ted for the use of the Committee on Science and Technology and the Committee on Foreign Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 421 0 WASHINGTON: 1980 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DON FUQUA, Florida, Chairman ROBERT A. ROE, New Jersey JOHN W. WYDLER, New York MIKE McCORMACK, Washington LARRY WINN. JR., Kansas GEORGE E. BROWN, JR., California BARRY M. GOLDWATER, JR., California JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York HAMILTON FISH, JS., New York RICHARD L. OTTINGER, New York MANUEL LUJAN, JR., New Mexico TOM HARKIN, Iowa HAROLD C. HOLLENBECK, New Jersey JIM LLOYD, California ROBERT K. DORNAN, California JEROME A. AMBRO, New York ROBERT S. WALKER, Pennsylvania MARILYN LLOYD BOUQUARD, Tennessee EDWIN B. FORSYTHE, NeW Jersey JAMES J. BLANCHARD, Michigan KEN KRAMER, Colorado DOUG WALGREN, Pennsylvania WILLIAM CARNEY, New York RONNIE G. FLIPPO, Alabama ROBERT W. DAVIS, Michigan DAN GLICKMAN, Kansas TOBY ROTH, Wisconsin ALBERT GORE, JR., Tennessee DONALD LAWRENCE RITTER, WES WATKINS, Oklahoma Pennsylvania ROBERT A. YOUNG, Missouri BILL ROYER, California RICHARD C. WHITE, Texas HAROLD L. VOLKMER, Missouri DONALD J. PEASE, Ohio HOWARD WOLPE, Michigan NICHOLAS MAVROULES, Massachusetts BILL NELSON, Florida BERYL ANTHONY, JR., Arkansas STANLEY N. LUNDINE, New York ALLEN E. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

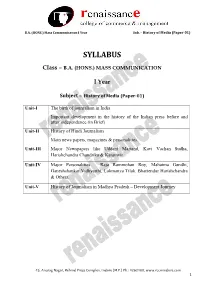

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-64, June 2011 Disengaged: Elite Media in a Vernacular Nation1 By Bob Calo Shorenstein Center Fellow, Spring 2011 Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley © 2011 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Journalists, by and large, regard the “crisis” as something that happened to them, and not anything they did. It was the Internet that jumbled the informational sensitivities of their readers, corporate ownership that raised suspicions about our editorial motives, the audience itself that lacked the education or perspective to appreciate the work. Yet, 40 years of polling is clear about one thing: The decline in trust and the uneasiness of the audience with the profession and its product started well before technology began to shred the conventions of the media. In 1976, 72% of Americans expressed confidence in the news. Everyone knows the dreary trend line from that year onward: an inexorable decline over the decades.2 And if we fail to examine our part in the collapse of trust, no amount of digital re-imagining or niche marketing is going to restore our desired place in the public conversation. Ordinary working people no longer see media as a partner in their lives but part of the noise that intrudes on their lives. People will continue to muddle through: voting or not voting, caring or not caring, but many of them are doing it, as they once did, without the companionship of the press. Now elites and partisans don’t have this problem, there are niches aplenty for them. -

![[Evillar] Tesis Doctoral](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0283/evillar-tesis-doctoral-1040283.webp)

[Evillar] Tesis Doctoral

Campus Universitario Dpto. de Teoría de la Señal y Comunicaciones Ctra. Madrid-Barcelona, Km. 36.6 28805 Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) Telf: +34 91 885 88 99 Fax: +34 91 885 66 99 DR. D. SANCHO SALCEDO SANZ, Profesor Titular de Universidad del Área de Conocimiento de Teoría de la Señal y Comunicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá, y y DR. D. JAVIER DEL SER LORENTE, Director Tecnológico del Área OPTIMA (Optimización, Modelización y Analítica de Datos) de la Fundación TECNALIA RESEARCH & INNOVATION, CERTIFICAN Que la tesis “Advanced Machine Learning Techniques and Meta-Heuristic Optimization for the Detection of Masquerading Attacks in Social Networks”, presentada por Esther Villar Ro- dríguez y realizada en el Departamento de Teoría de la Señal y Comunicaciones bajo nuestra dirección, reúne méritos suficientes para optar al grado de Doctor, por lo que puede procederse a su depósito y lectura. Alcalá de Henares, Octubre 2015. Fdo.: Dr. D. Sancho Salcedo Sanz Fdo.: Dr. D. Javier Del Ser Lorente Campus Universitario Dpto. de Teoría de la Señal y Comunicaciones Ctra. Madrid-Barcelona, Km. 36.6 28805 Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) Telf: +34 91 885 88 99 Fax: +34 91 885 66 99 Esther Villar Rodríguez ha realizado en el Departamento de Teoría de la Señal y Comunica- ciones y bajo la dirección del Dr. D. Sancho Salcedo Sanz y del Dr. D. Javier Del Ser Lorente, la tesis doctoral titulada “Advanced Machine Learning Techniques and Meta-Heuristic Optimiza- tion for the Detection of Masquerading Attacks in Social Networks”, cumpliéndose todos los requisitos para la tramitación que conduce a su posterior lectura. -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER