Quality in Journalism: Perceptions and Practice in an Indian Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012

he TIndian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 he © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi TIndian Parliament Editor T. K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). Lok Sabha Secretariat New Delhi Foreword In the over six decades that our Parliament has served its exalted purpose, it has witnessed India change from a feudally administered colony to a liberal democracy that is today the world's largest and also the most diverse. For not only has it been the country's supreme legislative body it has also ensured that the individual rights of each and every citizen of India remain inviolable. Like the Parliament building itself, power as configured by our Constitution radiates out from this supreme body of people's representatives. The Parliament represents the highest aspirations of the people, their desire to seek for themselves a better life. dignity, social equity and a sense of pride in belonging to a nation, a civilization that has always valued deliberation and contemplation over war and aggression. Democracy. as we understand it, derives its moral strength from the principle of Ahimsa or non-violence. In it is implicit the right of every Indian, rich or poor, mighty or humble, male or female to be heard. The Parliament, as we know, is the highest law making body. It also exercises complete budgetary control as it approves and monitors expenditure. -

The Blogization of Journalism

DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of School of Communication, Media and Theatre of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Lecture Room Linna K 103, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on May 17th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Communication, Media and Theatre Finland Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1418 ISBN 978-951-44-9450-5 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9451-2 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Preface I owe many thanks to you who made this work possible. I am grateful to you for making it worthwhile. It is hard to name you all, or rather it is impossible. By reading this, you certainly belong to those to whom I radiate my gratitude. Thank you all for your attention and critique, for a friendly talk and timely empathy. My special thanks to my teachers. To Ruslan Bekurov, my master’s thesis advisor at the university in Saint-Petersburg, who encouraged me to pursue the doctoral degree abroad. To Kaarle Nordenstreng, my local “fixer” and a brilliant mentor, who helped me with my first steps at the University of Tampere. -

Instead for Special Economic Zones in India Sumeet Jain

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 32 | Issue 1 Fall 2011 "You Say Nano, We Say No-No:" Getting a "Yes" Instead for Special Economic Zones in India Sumeet Jain Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Sumeet Jain, "You Say Nano, We Say No-No:" Getting a "Yes" Instead for Special Economic Zones in India, 32 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 1 (2011). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb/vol32/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. “You Say Nano, We Say No-No:” Getting a “Yes” Instead for Special Economic Zones in India Sumeet Jain* Abstract: Special Economic Zones (SEZs) have the potential to be valuable in- struments of economic growth and development in India. Yet, as a result of the resistance facing them, SEZs in India have not delivered economic benefits to their fullest potential. For this reason, reducing the resistance facing SEZs is critical to their success. This article seeks to reduce this resistance by devising a consensus-building plan based on a regulatory negotiation approach. The ar- ticle first shows that the past and present resistance facing India’s economic zones is a product of the lack of public input in the design of their policy. It then presents a platform for understanding the proponents’ and opponents’ argu- ments by distilling the current legislation and regulation governing India’s SEZ policy into a cohesive operational framework. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

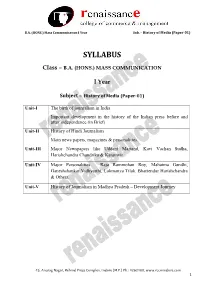

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

.BSDI Twelfth Series, Vol. I, No. I LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) First Session (Twelfth Lok Sabha) I Gazettes & Debetes Unit ...... Parliament Library BulldlnO @Q~m ~o. FBr.026 .. ~-- -- (Vol. I contains Nos. I to 8) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI I'ri ce .· Rs. 50. ()() 'VU"".&J:Ia.a.a IL.V .................. ~_ (Engl illl1 v«sian) 'lUeaJay, IIKcb 24, 1998/Chaitra 3, 1920 (Salta) Col.l1ine F« Raad CaltE!1ts/2 (fran &lltcn Salahuddin OWaisi Shri S. S. OWaiai below) 42/28 9/6 (fran below); SHRI ARIF HOfP.MW.D KHAN liIRI ARIF ~D KHAN 10/6 (fran below) j 11. /7,19: 13/3 12/5 (fran below) Delete "an" 13,19 (fran below) CalSSlsnal CalSE!1sual 22/25 hills hails CONTENTS {Twelfth Series. Vol. I. First Session. 199811920 (Seke)J No.2, Tuesday, March 24,1l1li Chain 3,1120 (lab) SUBJECT CoLUMNS MEMBERS SWORN 1-8 f)1:" SPEAKER 8-8 FI::L "'I-fE SPEAKER Shri Atal Biharl Vajpayee •.. 8-14 Shri Sharad Pawar ..• 14-15 Shrl Somnath Chatterjee .. 1~18 Shri Pumo A. Sangma .. 18-17 Kumari Mamata Banerjee .17-18 Shri Ram Vilas Paswan .•. 18 Shri R. Muthiah 19 Shri Mulayam Singh Yadav 19-20 Shri Lalu Prasad ... 21-22 Shri K. Yerrannaidu 22-23 Shri Naveen Patnaik 23 Shri Digvijay Singh .. 23-24 Shri Indrajit Gupta .. 24-25 Sardar Surjit Singh Bamala 2~2e Shri Murasoli Maran 28-28 Shri Shivraj ~. Palll .. ,. 28-29 Shri Madhukar Sirpotdar ... -_ ... 29-31 Shri Sanat Kumar Mandai 31 Shri P.C. Thomas 31-32 Kumari. -

JOU4004 HISTORY of JOURNALISM Fall 2020 | Class 15287, Section 2677 | Online 100% | 3 Credits

JOU4004 HISTORY OF JOURNALISM Fall 2020 | Class 15287, Section 2677 | Online 100% | 3 credits Dr. Bernell E. Tripp Office: 3055 Weimer Hall Office hours: Wednesdays 2:00 to 5:00 pm / All other available times by appointment. Office Phone: 352-392-2147 E-mail: [email protected] COURSE PURPOSE: To understand the media’s continued relevancy in the lives of its audience, it is much more important to remember – and see connections among – trends and significant social movements, and to connect those trends and movements to our modern lives. Students will be introduced to major issues and themes in the history of journalism in America. This thematic approach allows students to trace the major changes in the practice of journalism and mass communications and to understand the key instances in which the practice of journalism brought change to America in the larger societal, economic, cultural, and political spheres. COURSE STRUCTURE: This course is a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous learning tools through Canvas. Instructor lectures and guest speaker presentations will be a synchronous hybrid of Zoom meetings and/or prerecorded videos on class meeting days at the scheduled times (Tuesdays, 11:45 a.m.-1:40 p.m.; Thursdays, 12:50-1:40 p.m.). Synchronous online lectures will vary from one hour to 75 minutes, depending on the topic or the speaker. If possible, Thursdays will the designated day for asynchronous materials such as required supplemental videos, podcasts, PowerPoint presentations, etc., as well as assignment submissions for the research paper/project. Quizzes on weekly lectures, textbook readings, and supplemental materials will also be tentatively scheduled for completion by Saturdays by 11:59 p.m., unless there is a conflict on the calendar. -

JOUR 201: History of News in Modern America 4 Units Spring 2016 – Mondays & Wednesdays 3:30-4:50Pm Section: 21008D Location: ANN-L105A

JOUR 201: History of News in Modern America 4 Units Spring 2016 – Mondays & Wednesdays 3:30-4:50pm Section: 21008D Location: ANN-L105A Instructor: Mike Ananny, PhD Office: ANN-310B Office Hours: Mondays & Wednesdays 1:45-2:45pm Contact Info: [email protected] Teaching Assistant: Emma Daniels Office: ANN lobby Office Hours: Mondays 5-6pm Contact Info: [email protected] I. Course Description The goal of this course is to introduce students to key moments, debates, and ideas that have shaped U.S. journalism from about the Revolutionary War period through today. Since this is a survey class, we won’t be spending too much time on any one topic, time period, or analytical framework. Instead, each class will examine social, cultural, political, and technological aspects of U.S. journalism, getting a sense of its overarching history as a profession and public service. E.g., how has the press historically both depended upon and challenged the state? How has the press funded itself? Where did the idea of journalistic objectivity come from and what does it mean? How has news served both market and public interests? What legal decisions shape the press’s rights and responsibilities? How does the press organize itself, and reorganize itself in light of technological innovation? At several points in the course, world-class scholars and practitioners will give guest lectures, sharing with us their experiences studying and working within the U.S. press. We’ll hear first-hand accounts of what it’s been like to participate in different periods of modern American journalism, examine historical archives of press coverage, and will end the semester with a review of how today’s journalism is tied to historical patterns. -

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu John Harriss with Andrew Wyatt Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 | March 2016 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Harriss, John and Wyatt, Andrew, Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 50/2016, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, March 2016. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: John Harriss, jharriss (at) sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu 3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

Taking Stock, Placing Orders: a Historiographic Essay on the Business History of the Newspaper

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 312 639 CS 212 081 AUTHOR Smith, Carol; Dyer, Carolyn Stewart TITLE Taking Stock, Placing Orders: A Historiographic Essay on the Business History of the Newspaper. PUB DATE Aug 89 NOTE 63p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (72nd, Washington, DC, August 10-13, 1989). PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) -- Speeches /Conference Papers (150) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Business; Economics; *Historiography; *Journalism History; Literature Reviews; *Newspapers IDENTIFIERS *Business History; Journalism Research ABSTRACT This historiographic essay discusses and seeks to begin to address the need for a business history of the newspaper. The paper's first section clarifies the terms "business history," "economic history," "political history," and "history of economics," (which the paper suggests have been used interchangeably in the past despite the fact that they are not synonymous). This section extrapolates from the principal discipline of business history to construct a framework for the issues the business history of the newspaper would address. The paper's second section (through a partial review of the literature which concentrates on the scattered journal articles that historians frequently seem to overlook) reveals that while a substantial amount of work does need to be done in the business history of the newspaper, a body of knowledge on a broad range of the important issues exists and awaits historians' attention, criticism, and additions. One hundred eighty-eight notes are included. An appendix contains a six-page bibliography of the research published in scholarly journals. (SR) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. -

Tamil Nadu) [26 MAR

281 Budget (Tamil Nadu) [26 MAR. 1980] 1980-81—General 282 Discussion MR. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Tamil Nadu the Lok Sabha, be, taken into consideration." takes precedence. The questions were proposed. SHRI BHUPESH GUPTA; I know that Tamil Nadu is important SHRI BHUPESH GUPTA (West Bangal): May I seek one clarification? Does this MR. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: The Minister expenditure from the Consolidated Fund also has responded. That should be enough. include, their expenditure on the defections that are b^ing engineered in Tamil Nadu? SHRI BHUPESH GUPTA: We suggested that recognition should be announced during this session. SHRI R. VENKATARAMAN; I will answer it at the end. MR. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN; Tamil Nadu, please. SHRI ERA SEZHIYAN (Tamil Nadu): Sir, the demands for supplementary grants for SHRI ( BHUPESH GUPTA: It is clearly 1979-80 and the demands for grants of the stated in the manifesto. Government of Tamil Nadu for 1980-81 are under consideration. Tamil Nadu has come MR. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Please do not under the spell of President's rule for a second make a debate. time. In 1976 January, the DMK Ministry was dismissed unceremoniously and the Assembly was dissolved. Now, in 1980 February, the Ministry of the AI-ADMK has been dismissed I. THE BUDGET (TAMIL NADU) more unceremoniously. Sir, at least when the 1980-81—GENERAL DISCUSSION. Ministry of the DMK was dismissed in 1976, there, was a pretext of the Governor's report II. THE TAMIL NADU APPROPRIA wherein the reasons—however fallacious and TION (VOTE ON ACCOUNT) BILL, untrue these reports generally may be—have 1980. -

The History of Mexican Journalism

THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI BULLETIN VOLUME 29, NUMBER 4 JOURNALISM SERIES, NO. 49 Edited by Robert S. Mann The History of Mexican Journalism BY HENRY LEPIDUS ISSUED FOUR TIMES MONTHLY; ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER AT THE POSTOFFICE AT COLUMBIA, MISSOURl-2,500 JANUARY 21, 1928 2 UNIVERSfTY oF Mrssouru BULLETIN Contents I. Introduction of Printing into Mexico and the Forerunners of Journalism ______ 5 II. Colonial Journalism -------------------------------------------------------12 III. Revolutionary Journalism --------------------------------------------------25 IV. From Iturbide to Maximilian -----------------------------------------------34 V. From the Second Empire to "El lmparcial" --------------------------------47 VI. The Modern Period -------------------------------------------------------64 Conclusion ---------------------------___________________________________________ 81 Bibliography --------__ -------------__________ -----______________________________ 83 THE HISTORY OF MEXICAN JOURNALISM 3 Preface No continuous history of Mexican journalism from the earliest times to the present has ever been written. Much information on the subject exists, but nobody, so far as I know, has taken the trouble to assemble the material and present it as a whole. To do this within the limits necessarily imposed upon me in the present study is my principal object. The subject of Mexican journalism is one concerning which little has been written in the United States, but that fact need not seem su;prising. With compara tively few exceptions, Americans of international interests have busied themselves with studies of European or even Oriental themes; they have had l;ttle time for. the study of the nations south of the Rio Grande. More recently, however, the im portance of the Latin American republics, particularly Mexico, to us, has been in creasingly recognized, and the necessity of obtaining a clearer understanding of our southern neighbor has come to be more widely appreciated in the United States than it formerly was.