Developing a New Model of Primary Health Care in Goma (DRC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COD OP Roadcorridor Easter

N ! ! " 0 ! ' ! ! 5 ! 1 2 29°6'0"E 31°9'0"E n Mityana Wakiso ° o 27°55'0"E 28°20'0"E 28°45'0"E 29°10'0"E 29°35'0"E 30°0'0"E 30°25'0"E 30°50'0"E Kiaka 31°15'0"E 31°40'0"E 32°5'0"E 32°30'0"E 0 Biaboye 2 ! Beni! ! Ru! wenzori Hima o ! ! ! ! (!H Kololo 0 N!zenga i ! ! g Ntoyo 2 ! o t N Maboya Mutwanga Busega !\" ! ! 0 4 n ' a ! ! Bapere Vurondo 5 i ! n Kampala 1 l Ombole ! ! ! !Mpigi ° u Barumbi-Opienge ! 0 ZS Biena !Vuhombwe Kasese J u ZS Manguredjipa Kamwenge Kasugho !Kasese ! o ! o 1 p Butembo !Tabili V!uhovi ! ZS Mutwanga 0 !\ ! o C Kakinga ! !Mpondwe ! ! Bashu Entebbe p ! ! TERRITOIRE TERRITOIRE ! ! " ZS Opienge TERRITOIRE ! (!o " 0 Baswaga DE BUTEMBO 0 a ' DE OICHA Kikorongo ' u ! 0 Entebbe 0 l DE LUBERO ° TERRITOIRE ! ° 0 0 DE BAFWASENDE ! ! O U G A N D A ZS Musienene ! e d ! ! Mb! ua ZS Kyondo d !Lukaya Bakumu d'Angumu ! ! !Ibanda ! ! Lubero n e Boli !\ Kiruhura Lugazi ! ! ! o ! Parc National ! i ! u ! de la Maiko K!asugho t ZS Masereka !! Kisaka Amamula ! a ! q ZS Alimbongo !Oninga Masaka ! ! u ! ! i ! ! Lac Edward c S Bamate S " " 0 0 t Bamate ' ! ' a 5 ! Batangi ! 5 2 ZS Lubero 2 ! ° ° v 0 0 a é ! ' Kaseghe r Mbarara Kalisizo Kirumba !Ish!aka ! d ZS Pinga ! K!ikuv!o ! Bushenyi o c ! Bamate ! !Mbarara ! ! !Kayna Kabwohe s ZS Kayna ! o e Kafun!zo t Kanyabayo!nga P R O V I N C E D U ! i ! TERRITOIRE ! Ishasha m ! s Kihihi DE LUBUTU ! ! N O R D - K I V U ! ! ZS Kibirizi !Ishasha Kilambo ! ! s S S é " Bitule ZS Binza " 0 0 ' ' e Rwindi Rukungiri 0 ! 0 l 5 5 ° Isingiro ° d Ntungamo ! 0 ! ! 0 ! ! s Mutukula Wanianga !Kayonza r Kisharo -

The Eastern Border of DR Congo

Geothermal Exploration in D.R. Congo Vikandy S. Mambo Université Officielle de Ruwenzori,,, Butembo, North-Kivu, Eastern Congo 1 Geochemical Study of Thermal Springs in Eastern D. R. Congo • Mambo Vikandy S., (UOR, Butembo) • Kasereka Mahinda, Yalire Mapendano and Wafula Mifundu, (OVG, Goma) 2 Introduction • D.R. Congo is known to be endowed with natural resources: • Minerals • Fresh water • Timber • Electric power is therefore mainly Hydropower Which enormous untapped resources. • In spi te o f l arge resources, on ly 10% o f population use electricity 3 Index map of the western and eastern rifts in Africa 4 Major ‘Great Lakes’ of the East Africa rifts valleys 5 MjMajor volcanoes and dis tr ibu tion of major 20th Century lava flows 6 The most recent eruption • Mt.Nyiragongo eruption – Date : January 17, 2002 – Dea th to ll: 100 peop le (60 dea ths by explosion of petrol stations) – Damages: 30 % of Goma town destroyed or covered with thick lava 7 Vol cani c Disast er in 2002 Lava flow pushes the Lake 100 m as the Lava enters 70 m deep A house couvered with lava (6 personnes died inside)8 Destruction of Goma town, mostly the business area 9 The most recent major earthquakes • Kalehe earthquake occured on October 24, 2002 with 12 deaths •Buk av u ear th quak e on F ebr uar y 3, 2 008 with 44 deaths 10 Damages caused by earthquake in Kalehe (70 km south of Goma) on 24 Oct 2002 11 Earthquake parameters and disaster in Bukavu ● Time ; S und ay F eb . -

Report on Violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law by the Allied Democratic Forces Armed

UNITED NATIONS JOINT HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE OHCHR-MONUSCO Report on violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by the Allied Democratic Forces armed group and by members of the defense and security forces in Beni territory, North Kivu province and Irumu and Mambasa territories, Ituri province, between 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 July 2020 Table of contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Methodology and challenges encountered ............................................................................................ 7 II. Overview of the armed group Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) ................................................. 8 III. Context of the attacks in Beni territory ................................................................................................. 8 A. Evolution of the attacks from January 2015 to December 2018 .................................................. 8 B. Context of the attacks from 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 ............................................ 9 IV. Modus operandi............................................................................................................................................. 11 V. Human rights violations and abuses and violations of international humanitarian law . 11 A. By ADF combattants .................................................................................................................................. -

Bureau De La Division Epst Nord Kivu Ii a Butembo

COMPTE RENDU DE LA REUNION DU SOUS CLUSTER EDUCATION DU 26 FEVRIER 2020 LIEU : BUREAU DE LA DIVISION EPST NORD KIVU II A BUTEMBO Modération : NRC Secrétariat : EADEV AGENDA DE LA REUNION 1. Suivi des recommandations de la dernière réunion: 5 min. 2. Contexte sécuritaire et Alertes en éducation : 15 min 3. Positionnement des acteurs en éducation pour la réponse sur l’axe Mangina : 25 min 4. Plan d’action 2020 du sous cluster éducation au GNK : 30min 5. Activités réalisées par les acteurs et gaps en éducation : 10 min 6. Divers : 5min Participants/Organisation ou institution : UNICEF, L2RCONGO, Days for Girls, ADELUC, CREVF, CEFIDI, UEJEP RDC, NRC, EPST, EADEV, APETAMACO, AHADI RDC, MAAMS, ASOPROSAFD, OCHA, AVSI, ULCDDI, APDS Timing : de 10h40 à 12h30 SUJET DE POINTS DE DISCUSSION RECOMMANDATIONS L’AGENDA (par qui et quand) 1. Présentation des La réunion a été introduite par un mot de bienvenu prononcé par le PROVEDA participants EPST NK II à l’endroit de tous les acteurs présents. Il a aussi exprimé ses attentes vis-à-vis des défis auxquels est confronté le secteur de l’éducation dans le contexte de l’insécurité, la MVE mais aussi au contexte de la gratuité de l’enseignement de base. Une présentation nominative a, par la suite, été faite et c’était le début de l’effectivité de la réunion. SUJET DE RECOMMANDATION (S) RESPONSABLE (S) DE SUIVI ET NIVEAU DE REALISATION L’AGENDA REALISATION 2. Suivi des Du partage d’un rapport de Le rapport est déjà disponible et partagé AVSI et AHADI RD Congo recommandations l’évaluation multisectorielle des de la réunion du besoins en zone d’OICHA mois de janvier Du partage de l’outil 4W aux Le partage n’a pas été fait à cause du NRC 2020 membres du Sous Cluster Education programme du cluster national qui envisage renforcer les capacités des membres du sous cluster éducation sur les outils de collecte des données, y compris le 3 /4W. -

DRC), AFRICA | Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak

OPERATION UPDATE Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), AFRICA | Ebola Virus Disease outbreak Appeal №: n° Operations Update n° 8 Timeframe covered by this update: MDRCD026 Date of issue: 12 March 2020 34 months (May 2018 –February 2021) Operation start date: 21 May 2018 Operation timeframe: 34 months (May 2018 –February 2021) Glide №: Overall operation budget: CHF 56 One International Appeal amount EP-2018-000049-COD million initially allocated: CHF 500,000 + CHF EP-2018-000129-COD Budget Coverage as of 08 March 2021: 300,000 (Uganda) EP-2020-000151-COD CHF46.8m (84%) EP-2021-000014-COD Budget Gap: CHF9.2m (16%) N° of people to be assisted: 8.7 million people Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: In addition to the Democratic Republic of Congo Red Cross (DRC RC), the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) there is also French Red Cross and other in- country partner National Societies (Belgium Red Cross, Spanish Red Cross and Swedish Red Cross) and other Partner National Societies who have made financial contributions (American, British, Canadian, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, Swiss). Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Alongside these Movement partners, other national and international organizations are directly involved in the response to the Ebola epidemic. These include the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of Congo, WHO, UNICEF, MSF, Oxfam, Personnes vivant avec Handicap (PVH), Soutien action pour le développement de l’Afrique (SAD Africa), AMEF, ASEBO, MND, Humanitarian Action, Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (EPSP), Border Hygiene, IMC, The Alliance for International Medicine Action (ALIMA), IRC, Caritas, Mercy Corps, FHI 360, Africa CDC, CDC Atlanta, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO formerly DFID), OIM and the World Bank. -

In Search of Peace: an Autopsy of the Political Dimensions of Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo

IN SEARCH OF PEACE: AN AUTOPSY OF THE POLITICAL DIMENSIONS OF VIOLENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO By AARON ZACHARIAH HALE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Aaron Zachariah Hale 2 To all the Congolese who helped me understand life’s difficult challenges, and to Fredline M’Cormack-Hale for your support and patience during this endeavor 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I was initially skeptical about attending The University of Florida (UF) in 2002 for a number of reasons, but attending UF has been one of the most memorable times of my life. I have been so fortunate to be given the opportunity to study African Politics in the Department of Political Science in a cozy little town like Gainesville. For students interested in Africa, UF’s Center for African Studies (CAS) has been such a fantastic resource and meeting place for all things African. Dr. Leonardo Villalón took over the management of CAS the same year and has led and expanded the CAS to reach beyond its traditional suit of Eastern and Southern African studies to now encompass much of the sub-region of West Africa. The CAS has grown leaps and bounds in recent years with recent faculty hires from many African and European countries to right here in the United States. In addition to a strong and committed body of faculty, I have seen in my stay of seven years the population of graduate and undergraduate students with an interest in Africa only swell, which bodes well for the upcoming generation of new Africanists. -

Democratic Republic of Congo, First Quarter 2021

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, FIRST QUARTER 2021: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 12 August 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 30 July 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, FIRST QUARTER 2021: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 12 AUGUST 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 306 180 808 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 302 139 519 Development of conflict incidents from March 2019 to March 2021 2 Riots 146 69 108 Protests 103 4 5 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 73 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 2 0 0 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 932 392 1440 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 30 July 2021). Development of conflict incidents from March 2019 to March 2021 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 30 July 2021). 2 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, FIRST QUARTER 2021: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 12 AUGUST 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. -

Mass Killings in Beni Territory: Political Violence, Cover Ups, and Cooptation

Mass Killings in Beni Territory: Political Violence, Cover Ups, and Cooptation Investigative Report No2 September 2017 CONGO RESEARCH GROUP | GROUPE D’ÉTUDE SUR LE CONGO The Congo Research Group (CRG) is an independent, non-profit research project dedicated to understanding the violence that affects millions of Congolese. We carry out rigorous research on different aspects of the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. All of our research is informed by deep historical and social knowledge of the problem at hand, and we often invest months of field research, speaking with hundreds of people to produce a report. We are based at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University and we work in collaboration with the Centre d’études politiques at the University of Kinshasa. All of our publications, blogs and podcasts are available at www.congoresearchgroup. org and www.gecongo.org. Mass Killings in Beni Territory: Political Violence, Cover Ups, and Cooptation Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 5 2. Overview of Beni’s Mass Killings 8 The role of the ADF 11 Who was Responsible for the Killings? 13 3. Development of Beni’s Armed Politics (1980s-2010) 17 ADF/NALU’s Political Integration (1980s-1997) 18 Second Rebellion (1998-2003) 19 Post-Conflict Entangled Military Networks (2004-2010) 21 4. Mass Killings: The First Movers (2013) 29 The precursors to the massacres: ex-APC mobilization during the M23 Crisis (2012-2013) 29 Killings in Watalinga and Ruwenzor 31 5. Mass Killings in 2014-2015 38 Transitioning between waves of violence: First movers’ plans for killings (2014-2016) 39 Second movers: How the FARDC coopted existing groups 44 6. -

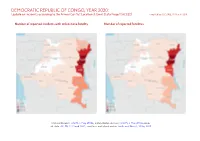

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of CONGO, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 1186 680 3254 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 1143 649 2319 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Protests 492 3 3 Riots 337 125 191 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 230 1 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 5 1 1 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3393 1459 5772 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Mukandala Et Al

Proceedings, 8th African Rift Geothermal Conference Nairobi, Kenya: 2 – 8 November 2020 Project for Development of Geothermal Resources in the Ruwenzori Sector, a Preliminary Report Pacifique S. Mukandala0, Georges M. Kasay 0, 0, Vikandy S. Mambo 0,0 1Department of Geology, Université Officielle de Ruwenzori, P.O. Box 560 Butembo 2Department of Geosciences, Pan African University of Life and Earth Sciences, University of Ibadan, Nigeria 3Department of Chemistry, Université de Kinshasa Email: [email protected],[email protected] ,[email protected] Keywords: Development, Geothermal, Resources, Energy, Geology, Hot springs, DR Congo ABSTRACT The Ruwenzori sector is located in the North-Kivu province, Beni territory in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) at the border with Uganda. It has several geothermal surface manifestations, mainly hot springs in Mutsora, Masambo, Kikura, Kyavitumbi and Kambo. All these geothermal manifestations have been mapped and are currently under geoscientific investigation. The area also has a large hydrologic network and several other geothermal fields which are yet to be discovered with further research. This paper focuses on reviewing the direct and indirect uses of known geothermal resources from which the local population of the Ruwenzori sector may benefit in the future. Applications related to direct use of geothermal manifestations include greenhouse in agriculture, hot water pool for bathing and medical benefits for tourist and local people, hot water for fish farming and other several applications. Indirect use of geothermal resources would generate energy for local communities and this would allow them to shift from traditional to modern agricultural practices. Electricity would benefit the local people in transforming products such as cocoa, palm oil, maize and preserving other crops after their harvest. -

Political Settlements and Armed Groups in the Congo Rift Valley Institute Usalama Project: Governance in Conflict

rift valley institute | usalama project governance in conflict political settlements research programme STABLE INSTABILITY POLITICAL SETTLEMENTS AND ARMED GROUPS IN THE CONGO RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE USALAMA PROJECT: GOVERNANCE IN CONFLICT Stable Instability Political settlements and armed groups in the Congo JUdITh VERwEIJEN Published in 2016 by the Rift Valley Institute 26 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1DF, United Kingdom PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya ThE USALAMA PROJECT The RVI Usalama Project is a field-based, partner-driven research initiative examining armed groups and their influence on society in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. ThE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. ThE AUThOR Judith Verweijen is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Conflict Research Group at Ghent University, Belgium. She is the Lead Researcher of the ‘Usalama Project: Governance in Conflict’. dISCLAIMER This report is an output from the Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP), funded by the UK Aid from the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. However, the views expressed and information contained in it are not necessarily those of or endorsed by DFID, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them. CREdITS RVI EXECUTIVE dIRECTOR: John Ryle RVI GREAT LAKES PROGRAMME MANAGER: Michel Thill RVI PROGRAMME MANAGER, PUBLICATIONS: Tymon Kiepe RVI PROGRAMME OFFICER, COMMUNICATIONS: Connor Clerke EdITOR: Kate McGuinness dESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-48-7 COVER: MONUC and Congolese government representatives in a meeting with FNI leader Peter Karim (right, back to camera) and his delegation to negotiate their integration into the national armed forces. -

Displacements in the Beni Territory, North Kivu Province Briefing Note, 30 July 2010

Displacements in the Beni Territory, North Kivu Province Briefing note, 30 July 2010 Headlines • Almost 90,000 people have been displaced in the Beni Territory of the North Kivu Province following armed confrontations. • The displaced are in need of protection, food, water, shelters, medicines and non-food items. • The presence of unaccompanied children was reported, as well as of other vulnerable people. Context • According to local authorities, almost 90,000 people are estimated to have fled their homes in the Beni Territory in the eastern North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), following military operations between the Forces armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) and the Allied Democratic Forces – National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (ADF- NALU). The military operation, called “Ruwenzori Operation”, started at the end of June 2010. • The ADF-NALU, based in western Uganda, was formed in 1996 and gradually expanded its activities to eastern DRC. After being largely destroyed in 2005 by the former United Nations Organization Mission in the DRC (MONUC) and the national army, this group gradually reorganised itself. • The epicentres of the fighting between the two belligerent parties, during which at least six civilians have died and dozen of people injured, are the towns of Eringeti, 85 km North of Beni and the town of Mutwanga, 42 km south-east from Beni. Fearing new attacks, the majority of the displaced population (70%) has fled preventively in different directions — from Eringeti towards the neighbouring Orientale Province, in the Ituri District — from Mutwanga towards the town of Beni and Lubango.