(OTC) Drugs for Recreational Purposes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme & Abstracts

The 57th Annual Meeting of the International Association of Forensic Toxicologists. 2nd - 6th September 2019 BIRMINGHAM, UK The ICC Birmingham Broad Street, Birmingham B1 2EA Programme & Abstracts 1 Thank You to our Sponsors PlatinUm Gold Silver Bronze 2 3 Contents Welcome message 5 Committees 6 General information 7 iCC maps 8 exhibitors list 10 Exhibition Hall 11 Social Programme 14 opening Ceremony 15 Schedule 16 Oral Programme MONDAY 2 September 19 TUESDAY 3 September 21 THURSDAY 5 September 28 FRIDAY 6 September 35 vendor Seminars 42 Posters 46 oral abstracts 82 Poster abstracts 178 4 Welcome Message It is our great pleasure to welcome you to TIAFT Gala Dinner at the ICC on Friday evening. On the accompanying pages you will see a strong the UK for the 57th Annual Meeting of scientific agenda relevant to modern toxicology and we The International Association of Forensic thank all those who submitted an abstract and the Toxicologists Scientific Committees for making the scientific programme (TIAFT) between 2nd and 6th a success. Starting with a large Young Scientists September 2019. Symposium and Dr Yoo Memorial plenary lecture by Prof Tony Moffat on Monday, there are oral session topics in It has been decades since the Annual Meeting has taken Clinical & Post-Mortem Toxicology on Tuesday, place in the country where TIAFT was founded over 50 years Human Behaviour Toxicology & Drug-Facilitated Crime on ago. The meeting is supported by LTG (London Toxicology Thursday and Toxicology in Sport, New Innovations and Group) and the UKIAFT (UK & Ireland Association of Novel Research & Employment/Occupational Toxicology Forensic Toxicologists) and we thank all our exhibitors and on Friday. -

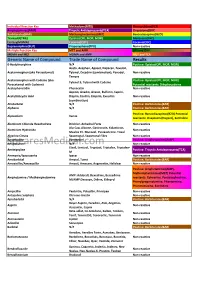

Cross Reaction Guide

Individual Reaction Key Methadone(MTD) Phencyclidine(PCP) Amphetamines(AMP) Tricyclic Antidepressants(TCA) Oxycodone(OXY) Barbiturates(BAR) Methamphetamines(MET) Benzodiazepines(BZO) Tramadol(TML) Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Marijuana(THC) Ecstasy(MDMA) Cotinine(COT) Cocaine(COC) Buprenorphine(BUP) Propoxyphene(PPX) Non-reactive Multiple Reaction Key MET and AMP OPI and OXY MDMA and MET MDMA and AMP MET and TCA Generic Name of Compound Trade Name of Compound Results 6-Acetylmorphine N/A Positive: Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Aceta, Acephen, Apacet, Dapacen, Feverall, Acetaminophen (aka Paracetamol) Tylenol, Excedrin (combination), Panadol, Non-reactive Tempra Acetaminophen with Codeine (aka Positive: Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Tylenol 3, Tylenol with Codeine Paracetamol with Codeine) Potential reactants: Dihydrocodeine Acetophenetidin Phenacetin Non-reactive Aspirin, Anadin, Anasin, Bufferin, Caprin, Acetylsalicyclic Acid Disprin, Ecotrin, Empirin, Excedrin Non-reactive (combination) Allobarbital N/A Positive: Barbiturates(BAR) Alphenol N/A Positive: Barbiturates(BAR) Positive: Benzodiazepines(BZO) Potential Alprazolam Xanax reactants: Oxaprozin (Daypro), Sertraline Aluminum Chloride Hexahydrate Drichlor, Anhydrol Forte Non-reactive Alu-Cap, Alisone, Gastrocote, Kolanticon, Aluminum Hydroxide Non-reactive Maalox TC, Mucogel, Pyrogastrone, Topal Alverine Citrate Spasmonal, Spasmonal Fibre Non-reactive Amantadine Symmetrel Positive: Amphetamines(AMP) SpearesMedical.comAminopyrine N/A Non-reactive Elavil, Lentizol, Tryptizol, Triptafen, Triptafen- Amitriptyline -

References to Argentina

References to Argentina Part 1 RECENT STATISTICS AND TREND ANALYSIS OF ILLICIT DRUG MARKETS A. EXTENT OF ILLICIT DRUG USE AND HEALTH CONSEQUENCES The Americas (pages 12 to 14 WDR 13) In the Americas, a high prevalence of most illicit drugs, essentially driven by estimates in North America, was observed, with the prevalence of cannabis (7.9 per cent) and cocaine (1.3 per cent) being particularly high in the region. South America, Central America and the Caribbean The annual prevalence of cocaine use in South America (1.3 per cent of the adult population) is comparable to levels in North America, while it remains much higher than the global average in Central America (0.6 per cent) and the Caribbean (0.7 per cent). Cocaine use has increased significantly in Brazil, Costa Rica and, to lesser extent, Peru while no change in its use was reported in Argentina. The use of cannabis in South America is higher (5.7 per cent) than the global average, but lower in Central America and Caribbean (2.6 and 2.8 per cent respectively). In South America and Central America the use of opioids (0.3 and 0.2 per cent, respectively) and Ecstasy (0.1 per cent each) also remain well below the global average. While opiates use remains low, countries such as Colombia report that heroin use is becoming increasingly common among certain age groups and socio-economic classes.30 Part 2 NEW PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES C. THE RECENT EMERGENCE AND SPREAD OF NEW PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES (page 67 WDR 13) Spread at the global level Number of countries reporting the emergence of new psychoactive substances Pursuant to Commission on Narcotic Drugs resolution 55/1, entitled “Promoting international cooperation in responding to the challenges posed by new psychoactive substances”, in 2012 UNODC sent a questionnaire on NPS to all Member States, to which 80 countries and territories replied. -

HANDBOOK of Medicinal Herbs SECOND EDITION

HANDBOOK OF Medicinal Herbs SECOND EDITION 1284_frame_FM Page 2 Thursday, May 23, 2002 10:53 AM HANDBOOK OF Medicinal Herbs SECOND EDITION James A. Duke with Mary Jo Bogenschutz-Godwin Judi duCellier Peggy-Ann K. Duke CRC PRESS Boca Raton London New York Washington, D.C. Peggy-Ann K. Duke has the copyright to all black and white line and color illustrations. The author would like to express thanks to Nature’s Herbs for the color slides presented in the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Duke, James A., 1929- Handbook of medicinal herbs / James A. Duke, with Mary Jo Bogenschutz-Godwin, Judi duCellier, Peggy-Ann K. Duke.-- 2nd ed. p. cm. Previously published: CRC handbook of medicinal herbs. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8493-1284-1 (alk. paper) 1. Medicinal plants. 2. Herbs. 3. Herbals. 4. Traditional medicine. 5. Material medica, Vegetable. I. Duke, James A., 1929- CRC handbook of medicinal herbs. II. Title. [DNLM: 1. Medicine, Herbal. 2. Plants, Medicinal.] QK99.A1 D83 2002 615′.321--dc21 2002017548 This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission, and sources are indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or for the consequences of their use. Neither this book nor any part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

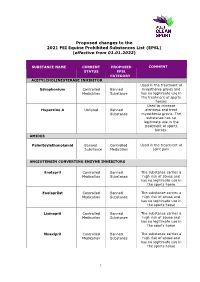

Proposed Changes to the 2021 FEI Equine Prohibited Substances List (EPSL) (Effective from 01.01.2022)

Proposed changes to the 2021 FEI Equine Prohibited Substances List (EPSL) (effective from 01.01.2022) SUBSTANCE NAME CURRENT PROPOSED COMMENT STATUS EPSL CATEGORY ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE INHIBITOR Used in the treatment of Edrophonium Controlled Banned myasthenia gravis and Medication Substance has no legitimate use in the treatment of sports horses Used to increase Huperzine A Unlisted Banned alertness and treat Substance myasthenia gravis. The substance has no legitimate use in the treatment of sports horses. AMIDES Palmitoylethanolamid Banned Controlled Used in the treatment of Substance Medication joint pain ANGIOTENSIN CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORS Enalapril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Enalaprilat Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Lisinopril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse Moexipril Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse 1 Perindoprilat Controlled Banned The substance carries a Medication Substance high risk of abuse and has no legitimate use in the sports horse ANTIHISTAMINES Antazoline Controlled Banned The substance has no Medication Substance legitimate use in the sports horse Azatadine Controlled Banned The substance has Medication Substance sedative effects -

A Anatomical Terms . Body Regions . . Abdomen . . . Groin

A ANATOMICAL TERMS . BODY REGIONS . ABDOMEN . GROIN . AXILLA . BACK . LUMBOSACRAL REGION . BREAST . BUTTOCKS . EXTREMITIES . AMPUTATION STUMPS . ARM . ELBOW . FOREARM . HAND . FINGERS . THUMB . SHOULDER . WRIST . LEG . ANKLE . FOOT . FOREFOOT . TOES . HALLUX . HEEL . METATARSUS . HIP . KNEE . THIGH . HEAD . EAR . VESTIBULE . FACE . EYE . CORNEA . MOUTH . JAW . TONGUE . TOOTH . NOSE . NECK . PHARYNX . PELVIS . PELVIC FLOOR . PERINEUM . SKIN . HAIR . NAILS . THORAX . TRUNK . CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM . BLOOD VESSELS . ARTERIES . AORTA . CAROTID ARTERIES . CORONARY VESSELS . PULMONARY ARTERY . VERTEBRAL ARTERY . MICROCIRCULATION . VEINS . CORONARY VESSELS . HEART . HEART VALVES . AORTIC VALVE . MITRAL VALVE . HEART VENTRICLE . MYOCARDIUM . CELLS . BLOOD CELLS . BLOOD PLATELETS . ERYTHROCYTES . LEUKOCYTES . BASOPHILS . LYMPHOCYTES . NEUTROPHILS . CELL MEMBRANE . SYNAPSES . CELL NUCLEUS . CELLS CULTURED . TUMOR CELLS CULTURED . CONNECTIVE TISSUE CELLS . CYTOPLASM . MITOCHONDRIA . EPITHELIAL CELLS . GERM CELLS . OVUM . SPERMATOZOA . MAST CELLS . NEUROGLIA . NEURONS . AXONS . NEURONS AFFERENT . NEURONS EFFERENT . MOTOR NEURONS . PHAGOCYTES . MACROPHAGES . DIGESTIVE SYSTEM . BILIARY TRACT . BILE DUCTS . GALLBLADDER . ESOPHAGUS . GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT . INTESTINES . ANAL CANAL . CECUM . COLON . DUODENUM . ILEUM . JEJUNUM . RECTUM . STOMACH . LIVER . PANCREAS . EMBRYONIC STRUCTURES . EMBRYO . FETUS . OVUM . PLACENTA . ENDOCRINE SYSTEM . ENDOCRINE GLANDS . ADRENAL GLANDS . PITUITARY GLAND . THYMUS GLAND . FLUIDS . BODY FLUIDS . BLOOD . CEREBROSPINAL -

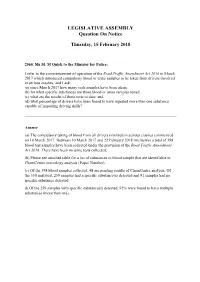

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question on Notice

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question On Notice Thursday, 15 February 2018 2560. Ms M. M Quirk to the Minister for Police; I refer to the commencement of operation of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016 in March 2017 which introduced compulsory blood or urine samples to be taken from drivers involved in serious crashes, and I ask: (a) since March 2017 how many such samples have been taken; (b) for what specific substances are those blood or urine samples tested; (c) what are the results of those tests to date; and (d) what percentage of drivers have been found to have ingested more than one substance capable of impairing driving skills? Answer (a) The compulsory taking of blood from all drivers involved in serious crashes commenced on 10 March 2017. Between 10 March 2017 and 22 February 2018 (inclusive) a total of 398 blood test samples have been collected under the provision of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016. There have been no urine tests collected. (b) Please see attached table for a list of substances in blood sample that are identifiable in ChemCentre toxicology analysis (Paper Number). (c) Of the 398 blood samples collected, 48 are pending results of ChemCentre analysis. Of the 350 analysed, 259 samples had a specific substance(s) detected and 91 samples had no specific substance detected. d) Of the 259 samples with specific substance(s) detected, 92% were found to have multiple substances (more than one). Detectable Substances in Blood Samples capable of identification by the ChemCentre WA. ACETALDEHYDE AMITRIPTYLINE/NORTRIPTYLINE -

One Step Drug Screen Test Strip (Urine) Package Insert

then react with the drug-protein conjugate and a visible colored line will show up in the test line region. The POSITIVE: One colored line appears in the control line region (C). No line appears in the test line region presence of drug above the cut-off concentration will saturate all the binding sites of the antibody. Therefore, (T). This positive result indicates that the drug concentration exceeds the detectable level. Effective date: 2014-07- 10 Number: 1156100501 the colored line will not form in the test line region. INVALID: Control line fails to appear. Insufficient specimen volume or incorrect procedural techniques are A drug-positive urine specimen will not generate a colored line in the test line region because of drug the most likely reasons for control line failure. Review the procedure and repeat the test using a new test. If competition, while a drug-negative urine specimen will generate a line in the test line region because of the the problem persists, discontinue using the lot immediately and contact your local distributor. absence of drug competition. To serve as a procedural control, a colored line will always appear at the control QUALITY CONTROL One Step Drug Screen Test Strip (Urine) line region, indicating that proper volume of specimen has been added and membrane wicking has occurred. REAGENTS A procedural control is included in the test. A colored line appearing in the control line region (C) is Package Insert considered an internal procedural control. It confirms sufficient specimen volume, adequate membrane Each test contains specific drug antibody-coupled particles and corresponding drug-protein conjugates. -

Reversible Worsening of Psychosis Due to Benzydamine in a Schizoaffective Young Girl Who Is Already Under Treatment with Antipsychotics

Olgu Sunumlar› / Case Reports Reversible Worsening of Psychosis Due to Benzydamine in a Schizoaffective Young Girl Who is Already under Treatment with Antipsychotics Mehmet Kerem Doksat ÖZET: ABSTRACT: Antipsikotiklerle tedavi alt›nda olan flizoaffek- Reversible worsening of psychosis due to tif bir genç k›zda benzidamin kullan›lmas›na benzydamine in a schizoaffective young girl ba¤l› olarak geliflen reversibl psikoz kötülefl- who is already under treatment with mesi antipsychotics Ülkemizde Tantum, Tanflex, Benzidan gibi isimlerle sat›lan Benzydamine, available as the hydrochloride form, is an benzidamid hidroklorid, antienflamatuar ve analjezik ola- anti-inflammatory drug providing both rapid and rak s›kl›kla kullan›lan bir ilâçt›r. 500 ilâ 3000 mg gibi oral extended pain relief in many painful inflammatory dozlarda “deliran” (kafa bulucu) etkisi görülür; yarat›c›l›¤› conditions. In oral dosages of 500 mg to 3000 mg it is a artt›r›c› hallüsinozise (ego-distonik hallüsinasyonlara) ve “deliriant” and CNS stimulant, popular in Poland and Brazil. öforiye yol açt›¤› için, Polonya ve Brezilya’da s›kl›kla kulla- In Brazil it is so popular that many people use it for n›lmaktad›r. Yüksek dozlarda panoya, a¤›z kurulu¤u ve recreational purposes. A person in a “benzydamine trip” konvülsiyonlar görülebilir ve 2000–3000 mg dozlar›nda may experience a feeling of well-being, euphoria and in merkezî sinir sistemini uyar›c› etkisi belirginleflir. Bu “trip- higher doses hallucinations, paranoia, dry mouth and ler” bilerek veya kazaen al›nan yüksek dozlardan sonra or- convulsions may also be experienced. In dosages of 750 taya ç›k›p, ilâç kesilince 2 ilâ 3 günde kendili¤inden düzelir. -

Diphenhydramine-Containing Medicines

DocuSign Envelope ID: A870FCE7-A2BC-4E84-A360-1F3B93214B6D Medicine Safety Alert Diphenhydramine-containing medicines MEDICINE SAFETY ALERT DIPHENHYDRAMINE-CONTAINING MEDICINES SAHPRA alerts all healthcare professionals about the risk of serious heart problems, seizures, coma and death associated with the use of high doses of diphenhydramine- containing medicines The South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) wishes to alert healthcare professionals about the risk of serious heart problems, seizures, coma and death associated with the use of high doses of diphenhydramine-containing medicines. An online challenge known as “the Benadryl Challenge” has recently been in the news. Benadryl® is not registered in South Africa (SA), but several products available in SA contain diphenhydramine and may be similarly misused (see SAHPRA website for a list of diphenhydramine-containing medicines). “Benadryl Challenge” is a TikTok trend, which encourages social media users through an online video to overdose on over-the-counter (OTC) Benadryl® in order to hallucinate. At least one teenager has reportedly died due to complications resulting from attempting the “challenge” in August 2020. These incidents prompted the manufacturer of Benadryl® in the United States, in collaboration with the US regulator, TikTok and other social media platforms, to remove content that displays the “challenge”. Diphenhydramine is mainly used to treat symptoms of allergic reactions (runny nose; sneezing; itchy, watery eyes; and itchy throat), insomnia, and -

Handouts from 4-20-21 Training

New Trends in Substance Abuse NY STOP DWI 2021 Lynn Riemer Ron Holmes, MD 720-480-0291 720-630-5430 [email protected] [email protected] www.actondrugs.org Facebook/ACTonDrugs Indicators of Drug or Alcohol Abuse or Misuse: Behavioral Physical - Abnormal behavior - Breath or body odor - Exaggerated behavior - Lack of coordination - Boisterous or argumentative - Uncoordinated & unsteady gait - Withdrawn - Unnecessary use of arms or supports for balance - Avoidance - Sweating and/or dry mouth - Changing emotions & erratic behavior - Change in appearance Speech Performance - Slurred or slow speech - Inability to concentrate - Nonsensical patterns - Fatigue & lack of motivation - Confusion - Slowed reactions - Impaired driving ability The physiologic factors predisposing to addiction Nearly every addictive drug targets the brain’s reward system by flooding the circuit with the neurotransmitter, dopamine. Neurotransmitters are necessary to transfer impulses from one brain cell to another. The brain adapts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine by ultimately producing less dopamine and by reducing the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. As a result, two important physiologic adaptations occur: (1) the addict’s ability to enjoy the things that previously brought pleasure is impaired because of decreased dopamine, and (2) higher and higher doses of the abused drug are needed to achieve the same “high” that occurred when the drug was first used. This compels the addict to increase drug consumption to increase dopamine production leading to physiologic addiction with more and more intense cravings for the drug. The effects of addiction on the brain Nearly all substances of abuse affect the activity of neurotransmitters that play an important role in connecting one brain cell to another. -

Indicators of Drug Or Alcohol Abuse Or Misuse: Behavioral Physical

New Trends in Substance Abuse Fall Clinics 2020 Lynn Riemer Ron Holmes, MD 720-480-0291 720-630-5430 [email protected] [email protected] www.actondrugs.org Facebook/ACTonDrugs Indicators of Drug or Alcohol Abuse or Misuse: Behavioral Physical - Abnormal behavior - Breath or body odor - Exaggerated behavior - Lack of coordination - Boisterous or argumentative - Uncoordinated & unsteady gait - Withdrawn - Unnecessary use of arms or supports for balance - Avoidance - Sweating and/or dry mouth - Changing emotions & erratic behavior - Change in appearance Speech Performance - Slurred or slow speech - Inability to concentrate - Nonsensical patterns - Fatigue & lack of motivation - Confusion - Slowed reactions - Impaired driving ability The physiologic factors predisposing to addiction Nearly every addictive drug targets the brain’s reward system by flooding the circuit with the neurotransmitter, dopamine. Neurotransmitters are necessary to transfer impulses from one brain cell to another. The brain adapts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine by ultimately producing less dopamine and by reducing the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. As a result, two important physiologic adaptations occur: (1) the addict’s ability to enjoy the things that previously brought pleasure is impaired because of decreased dopamine, and (2) higher and higher doses of the abused drug are needed to achieve the same “high” that occurred when the drug was first used. This compels the addict to increase drug consumption to increase dopamine production leading to physiologic addiction with more and more intense cravings for the drug. The effects of addiction on the brain Nearly all substances of abuse affect the activity of neurotransmitters that play an important role in connecting one brain cell to another.